No Escape: The Legacy of Attica Lives!

“Attica! Attica! Attica!” More than merely a quote from the iconic 1975 film Dog Day Afternoon, this is a defiant chant meant to evoke the searing memories of what took place over the course of five days in September of 1971 at an infamously inhospitable and systemically racist prison facility in Attica, New York. These events came to represent the power of organized resistance in the face of oppression.

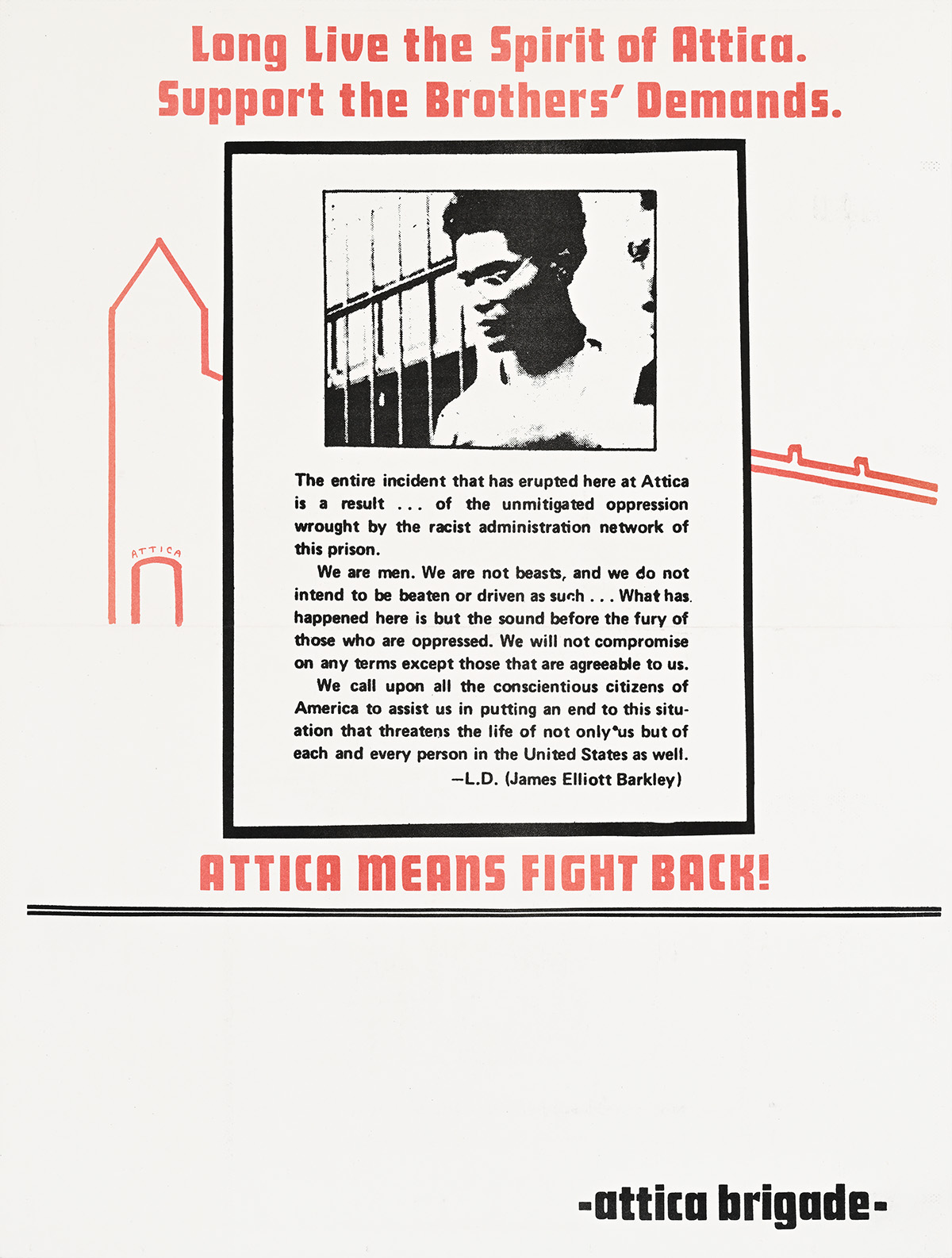

The Attica uprising was the culmination of a racial reckoning that had been brewing in the United States alongside serious disturbances in prisons and various protest movements over the previous decade. It remains the largest and the bloodiest prison rebellion in U.S. history. Many of the incarcerated men had the goal of pushing the prison—known as “The Last Stop” because of its particularly brutal reputation—to address the inhumane treatment and routine abuses perpetrated by the prison’s guards and to adopt reforms. They also demanded improvements to medical services, religious freedom, expanded visitation rights, and access to basic hygiene amenities like daily showers and toothbrushes. To this end, on September 9, many of the prisoners rioted and took 42 members of the prison staff hostage.

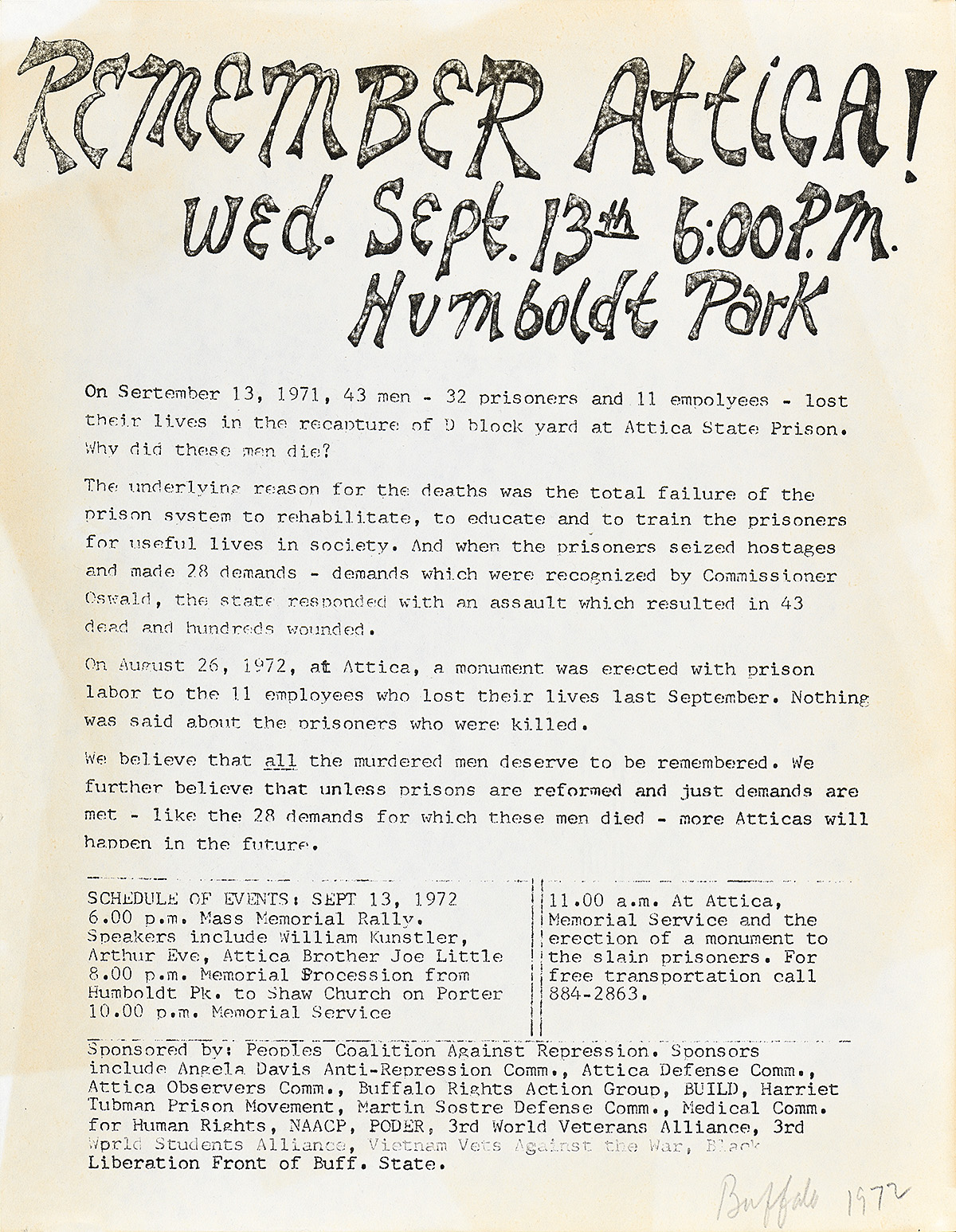

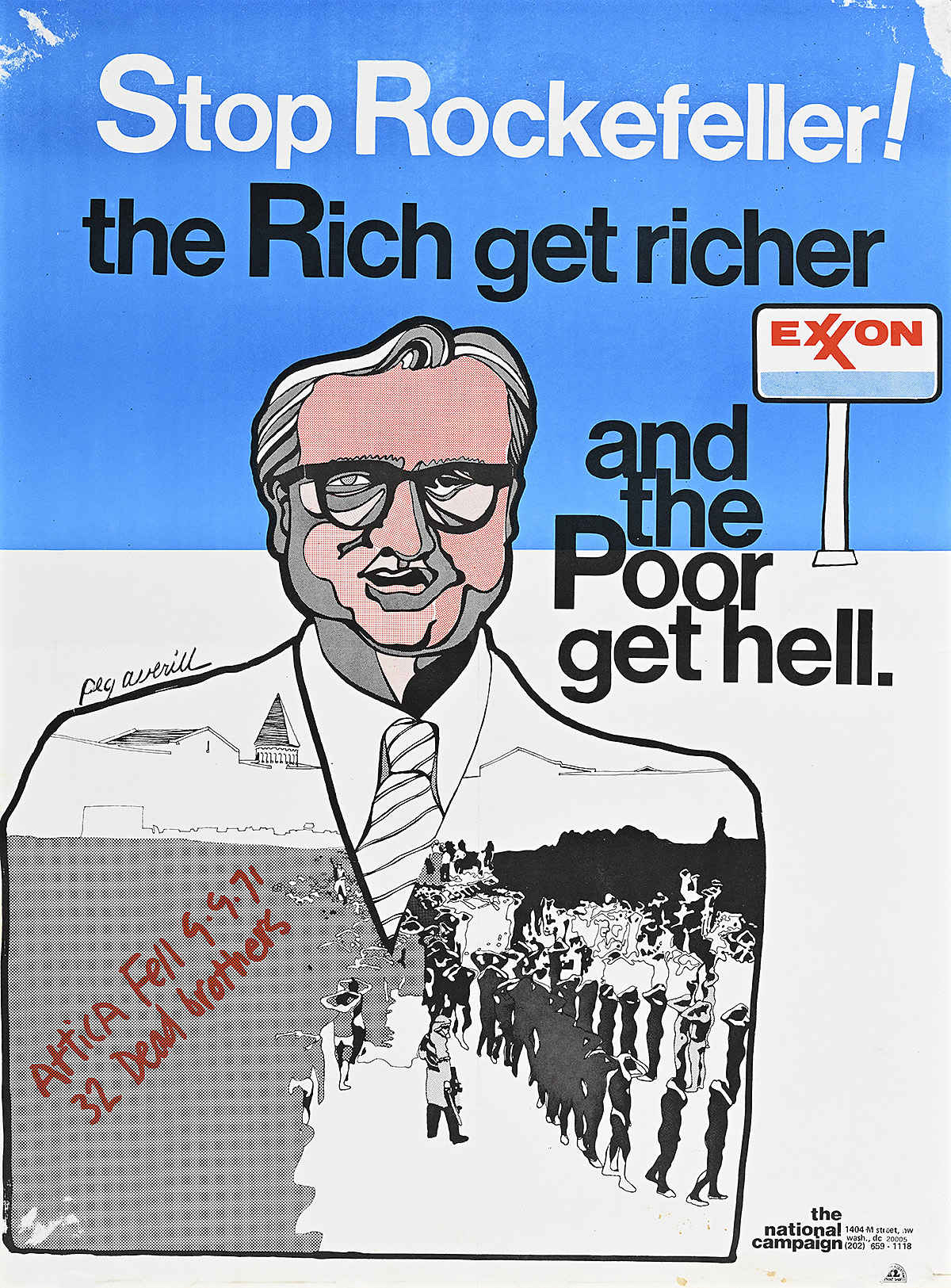

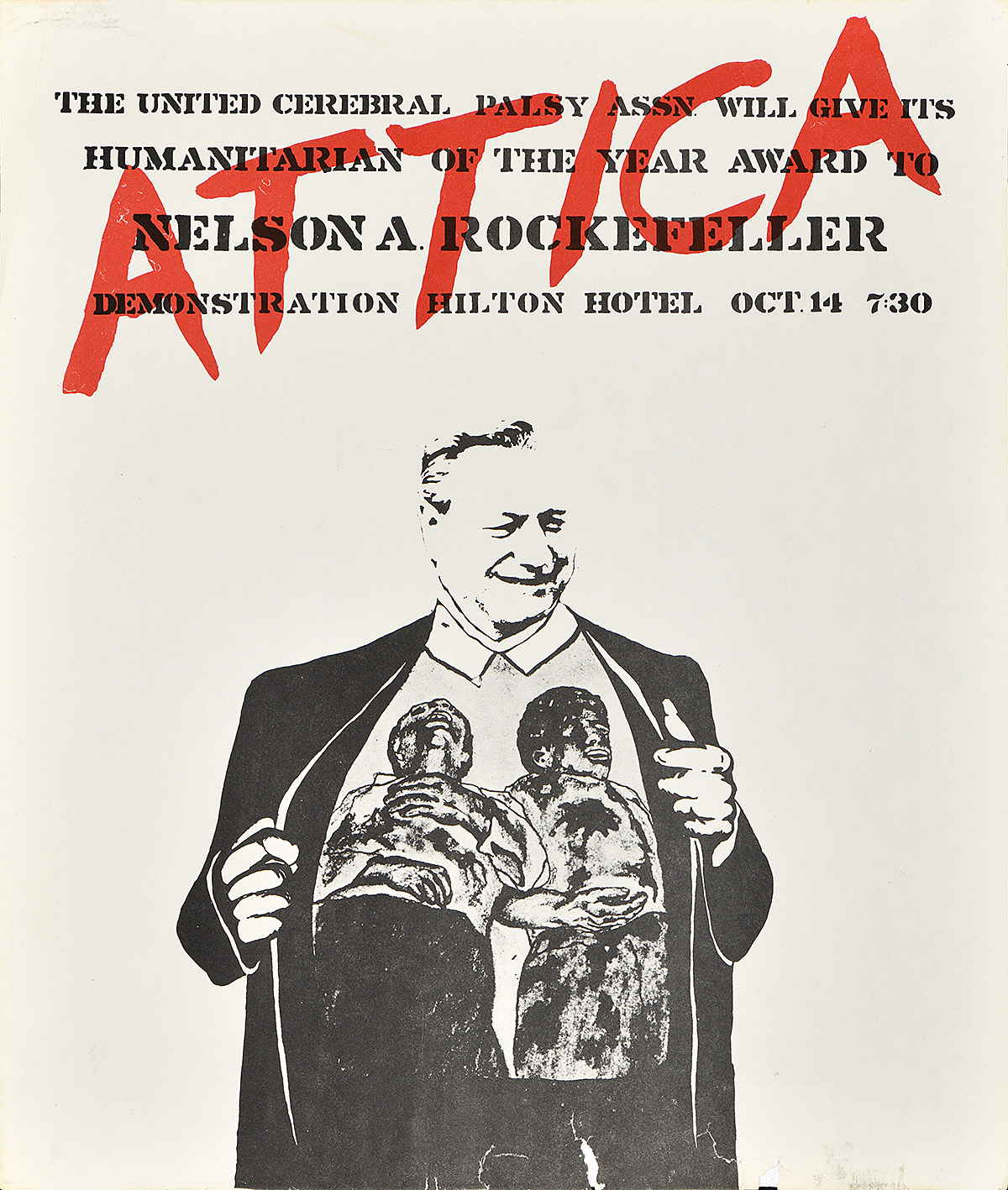

After four days, the tense negotiations between the authorities, the incarcerated men, and the neutral parties brought in to broker a peaceful settlement, broke down completely. Nelson Rockefeller, the relatively moderate Republican governor of New York, eager to assert his “law and order” bona fides, approved a raid on the facility. On September 13, state police officers stormed the prison, killing 29 prisoners and 10 hostages.

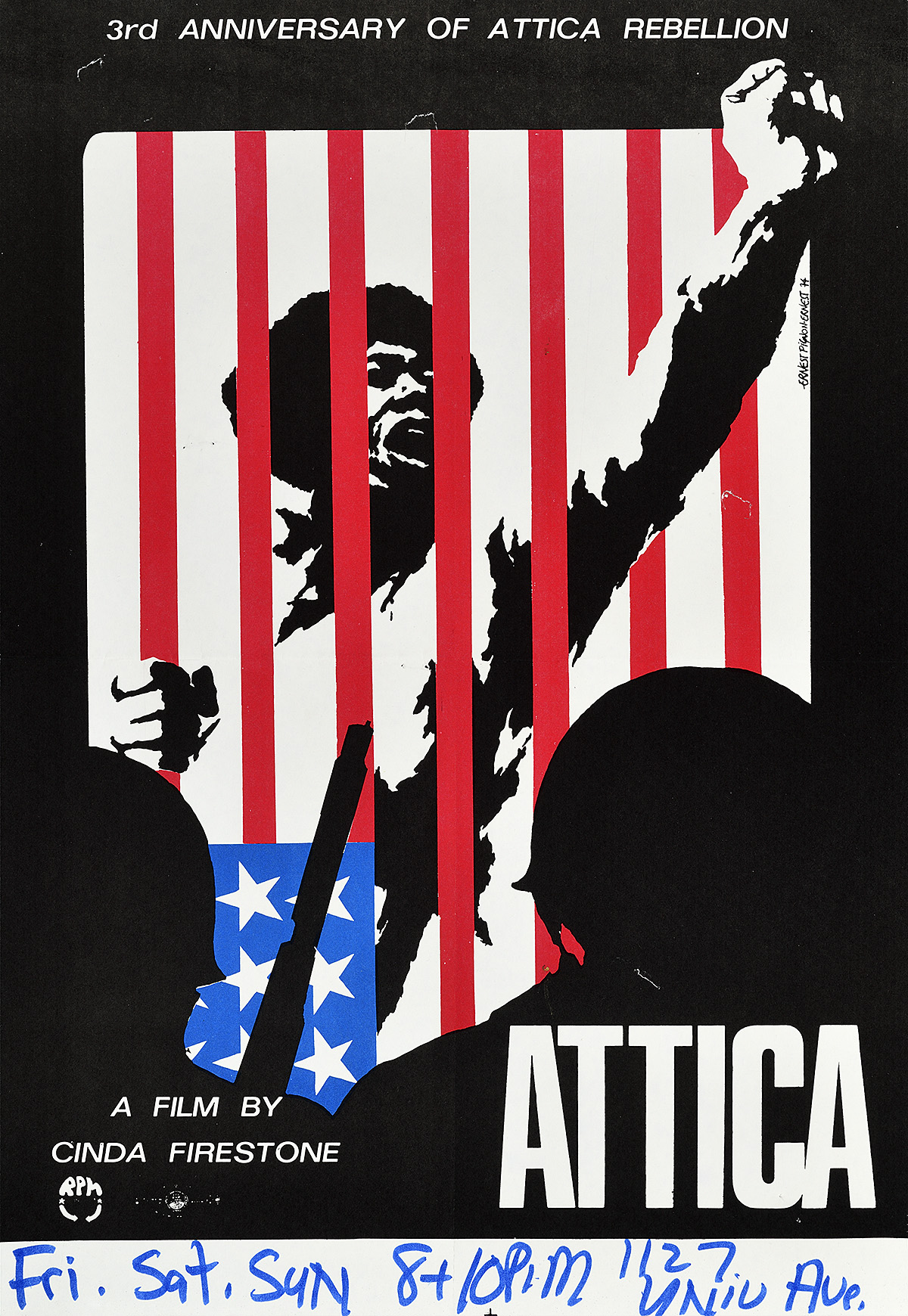

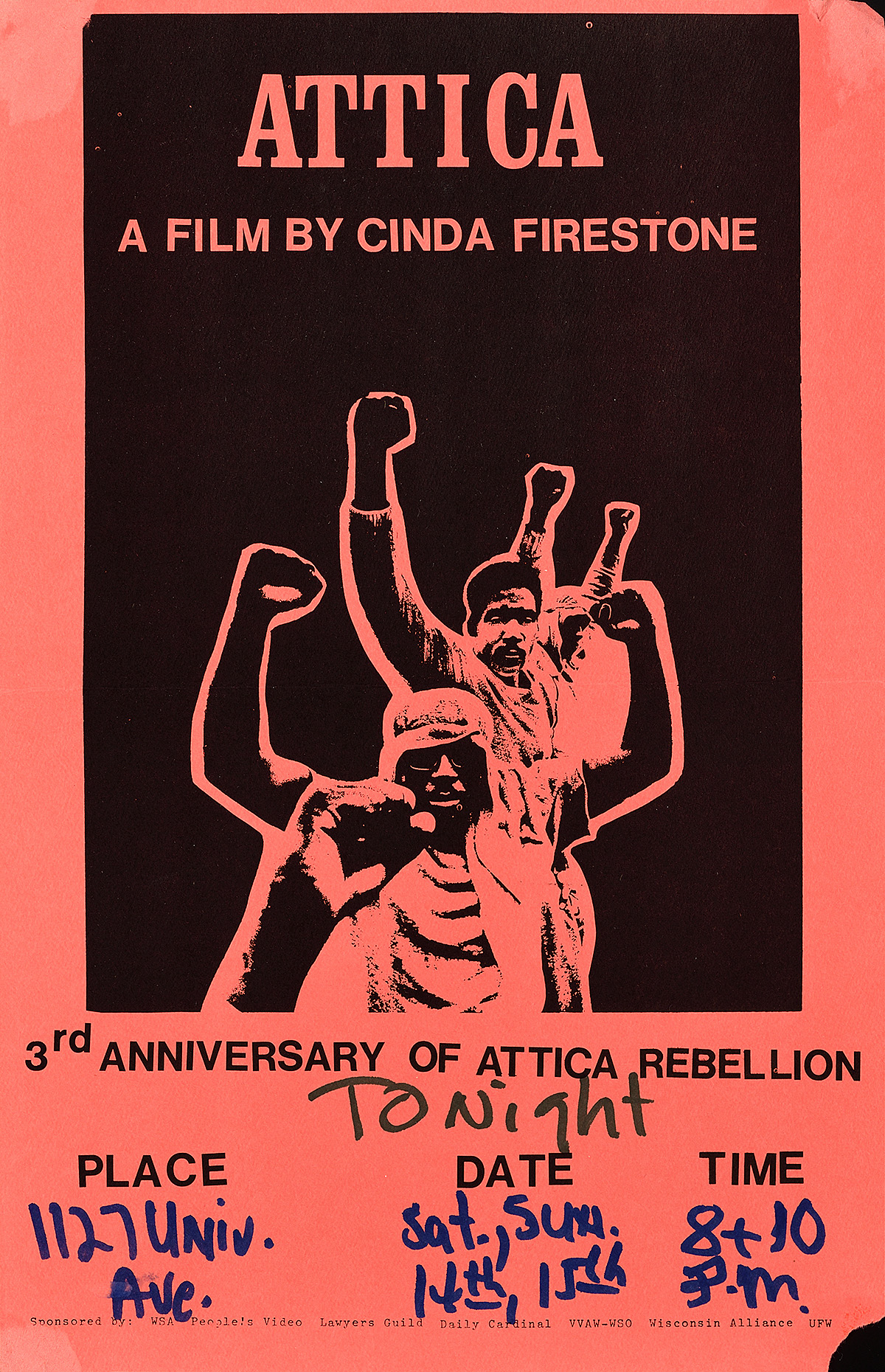

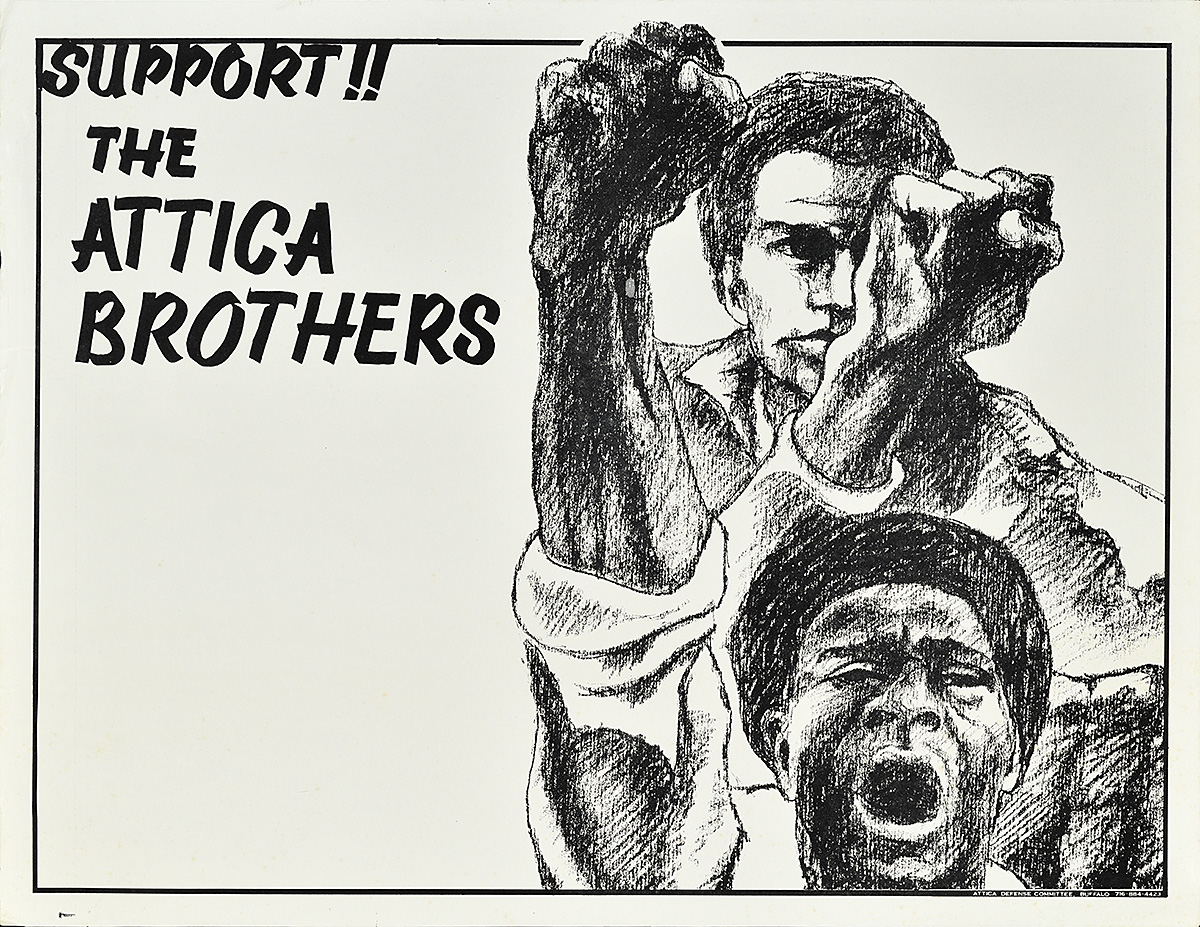

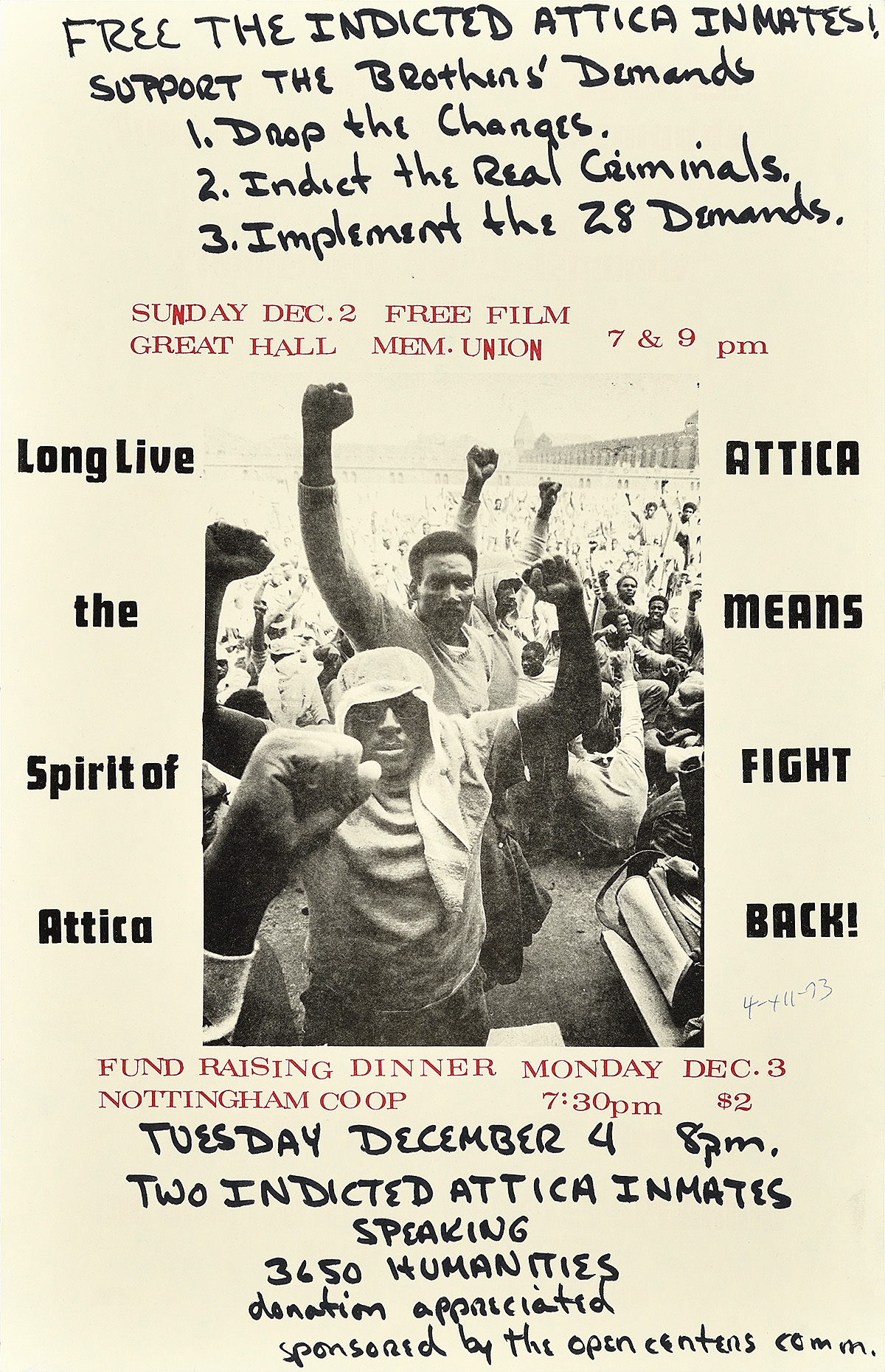

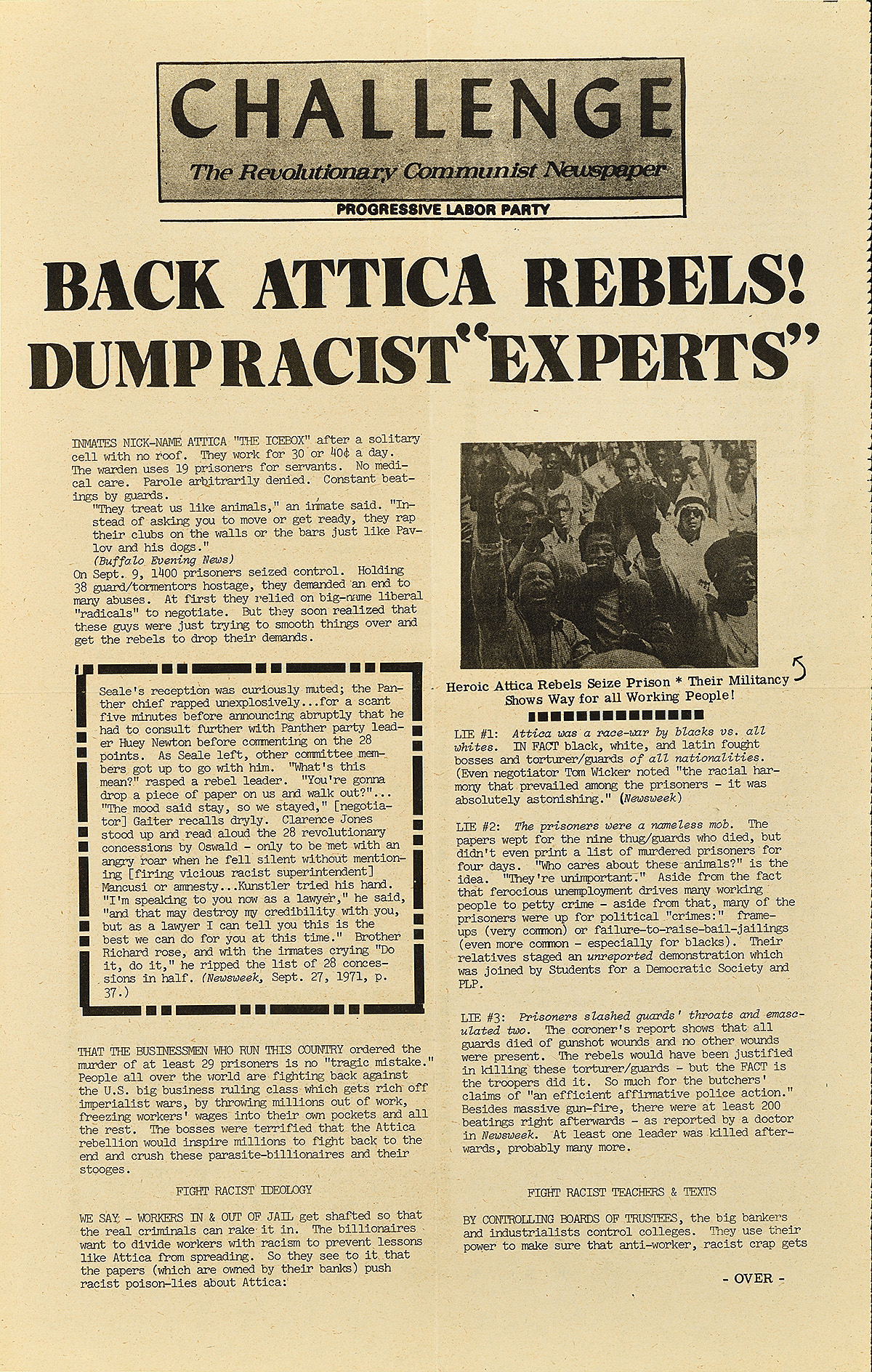

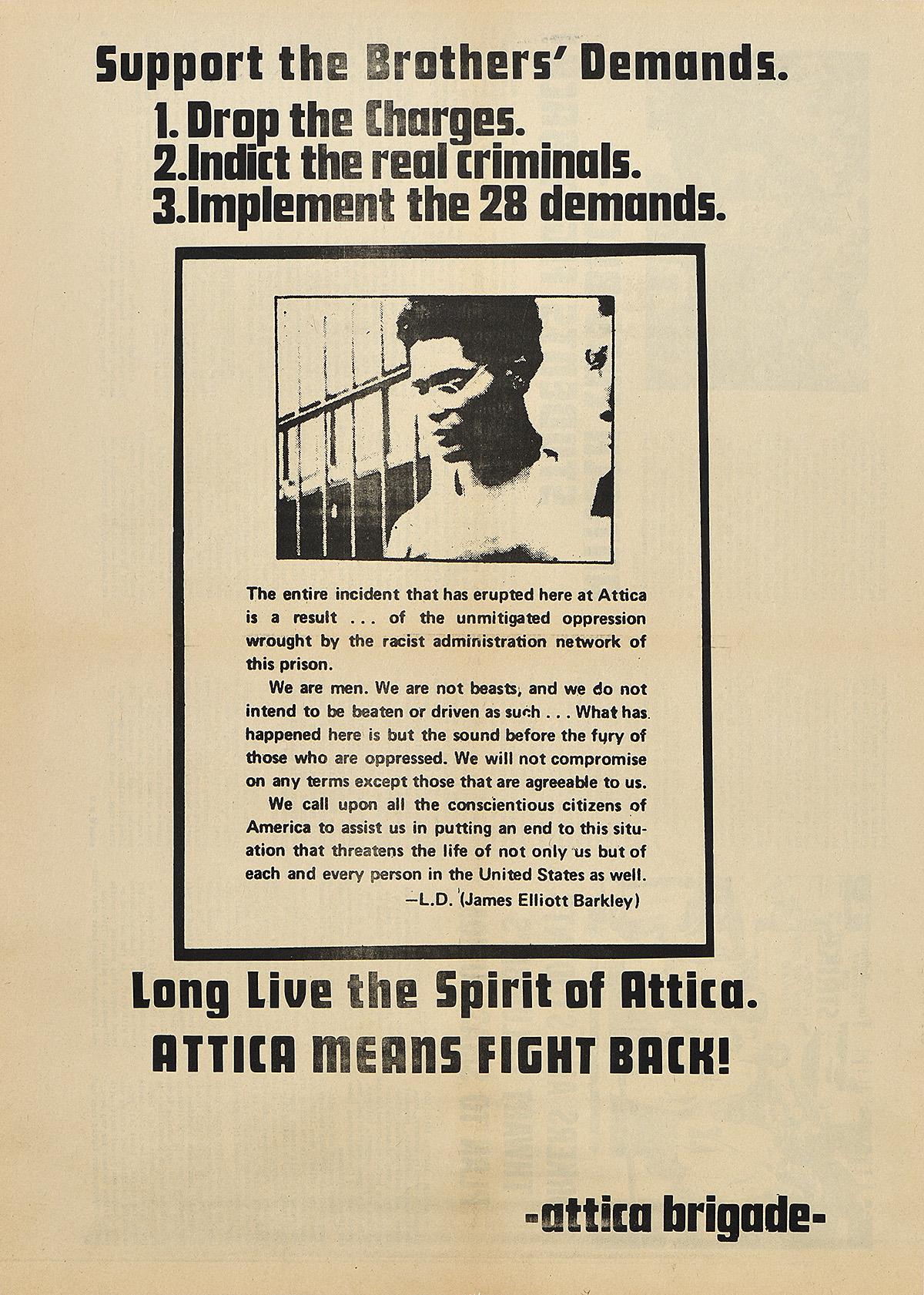

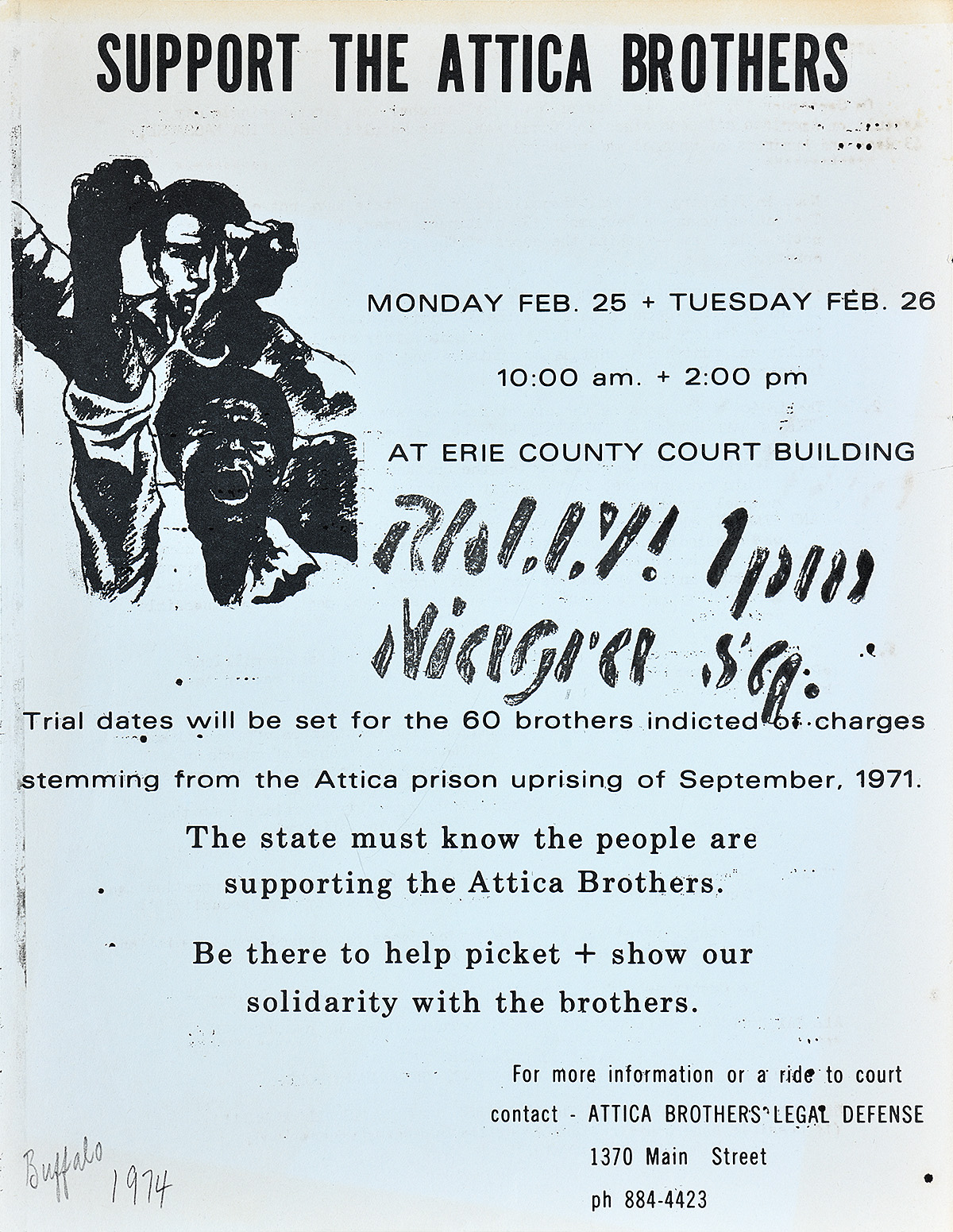

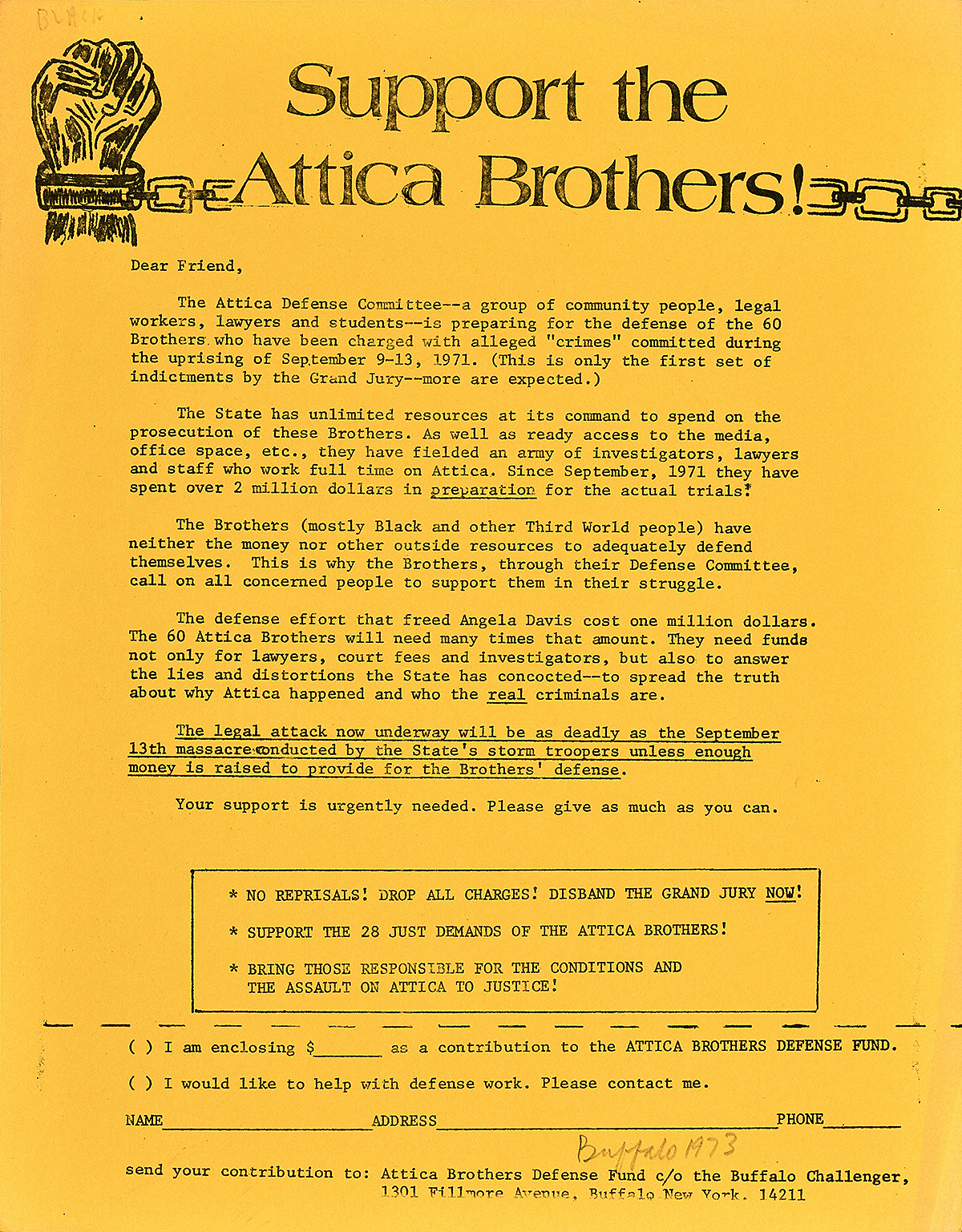

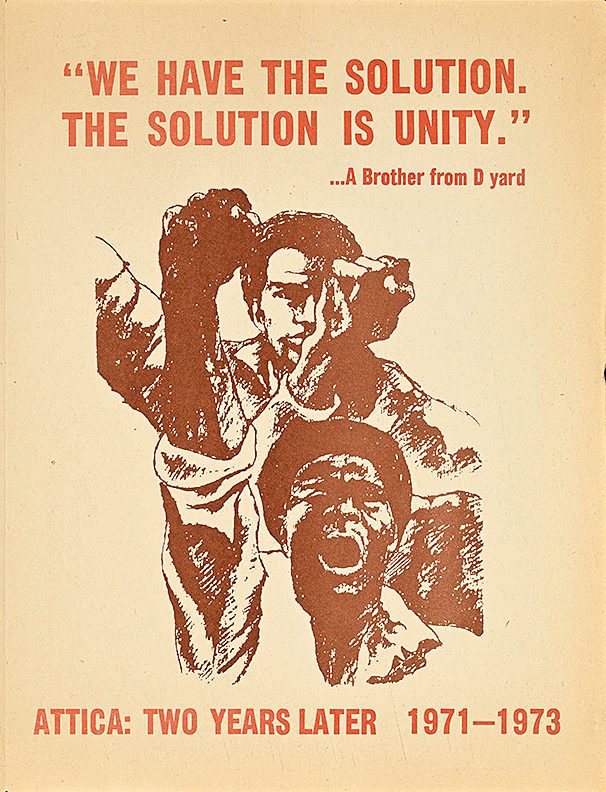

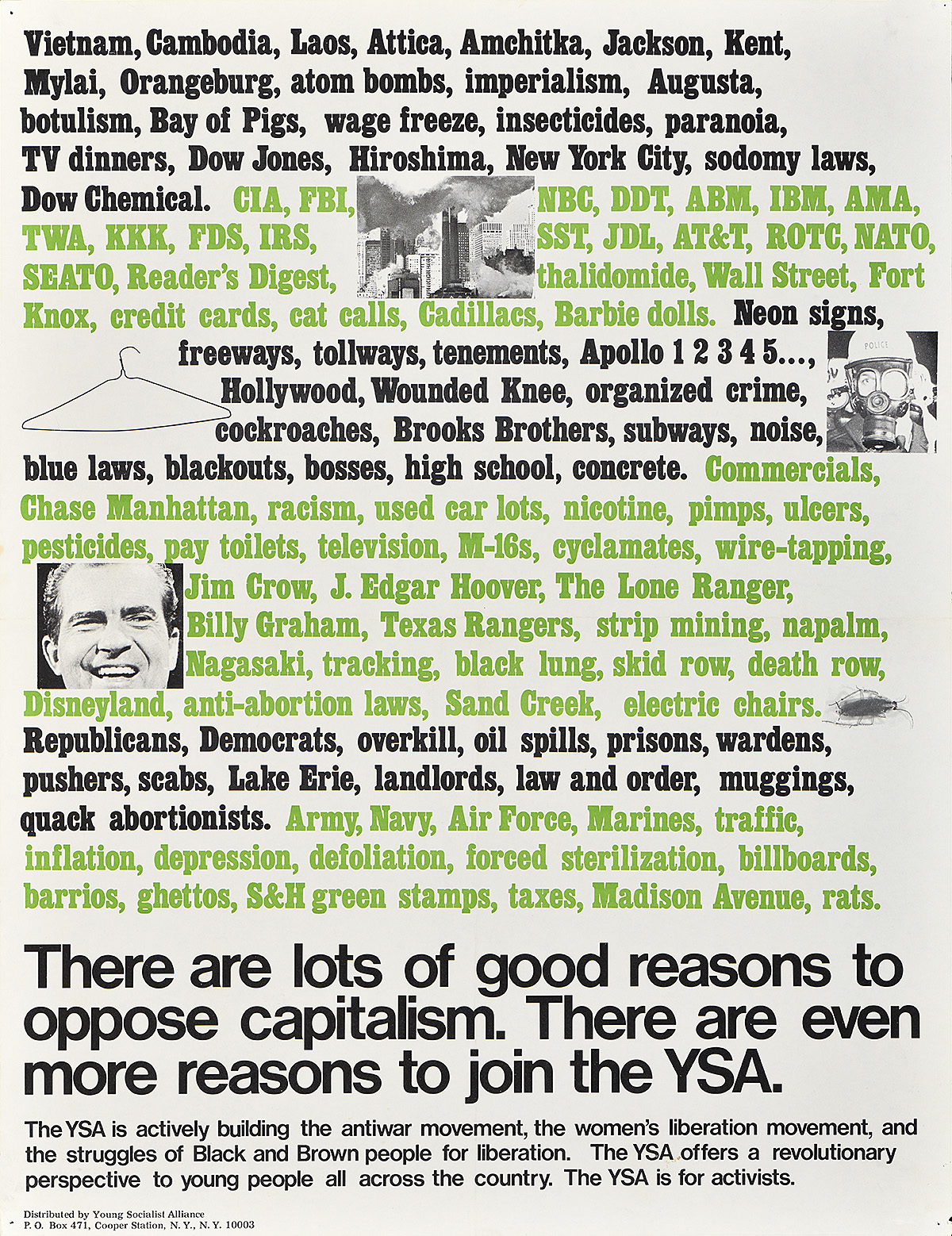

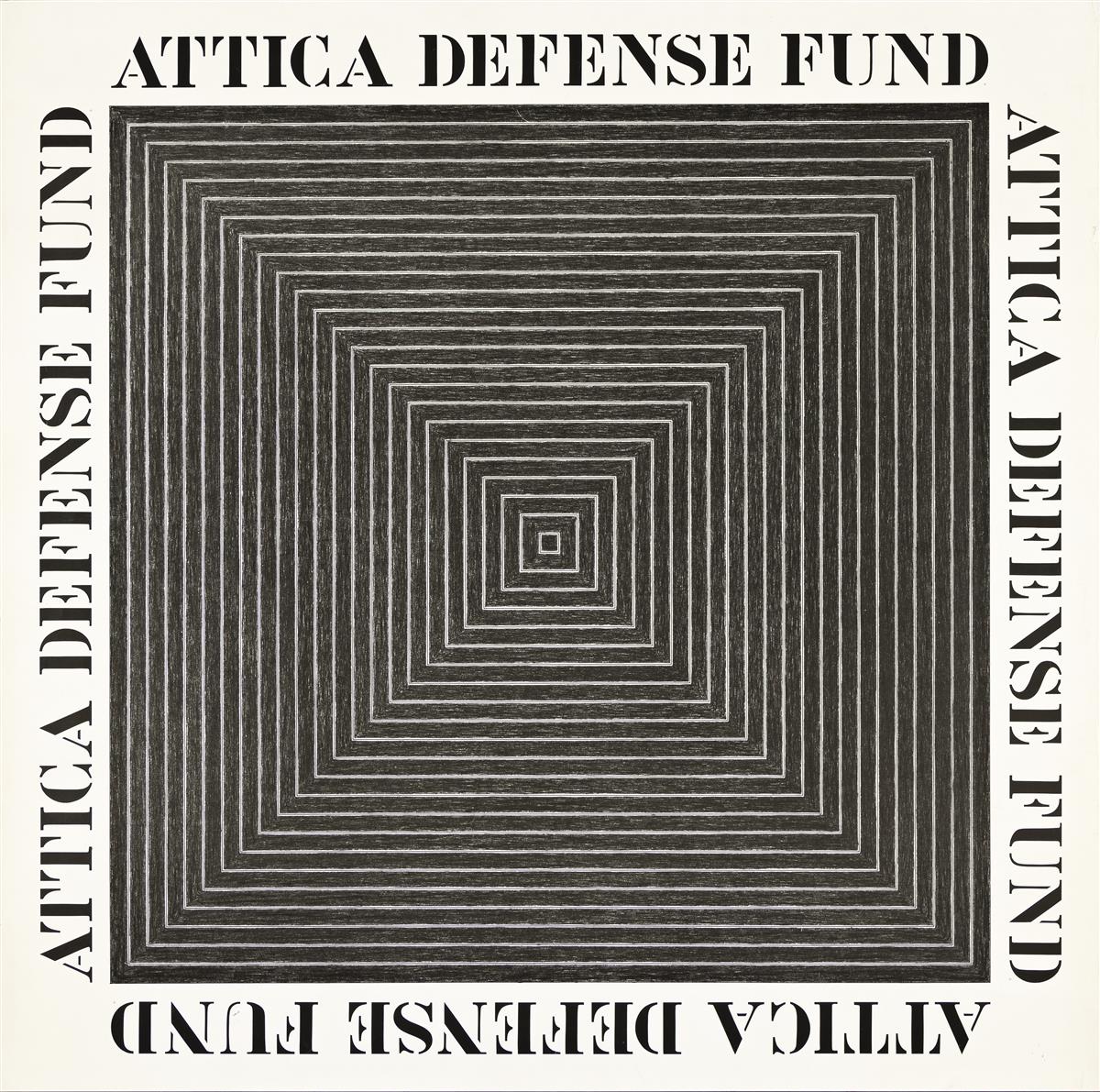

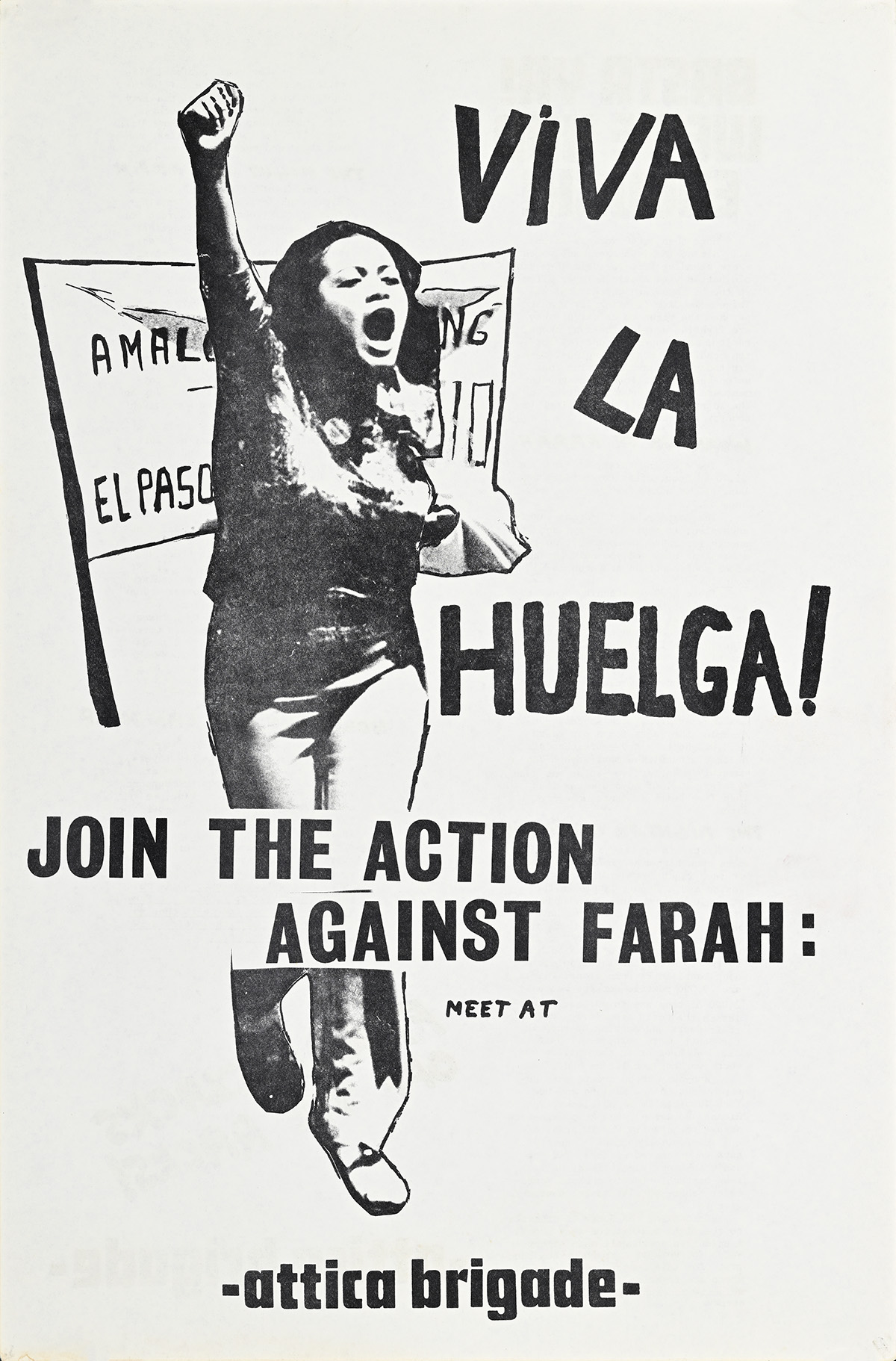

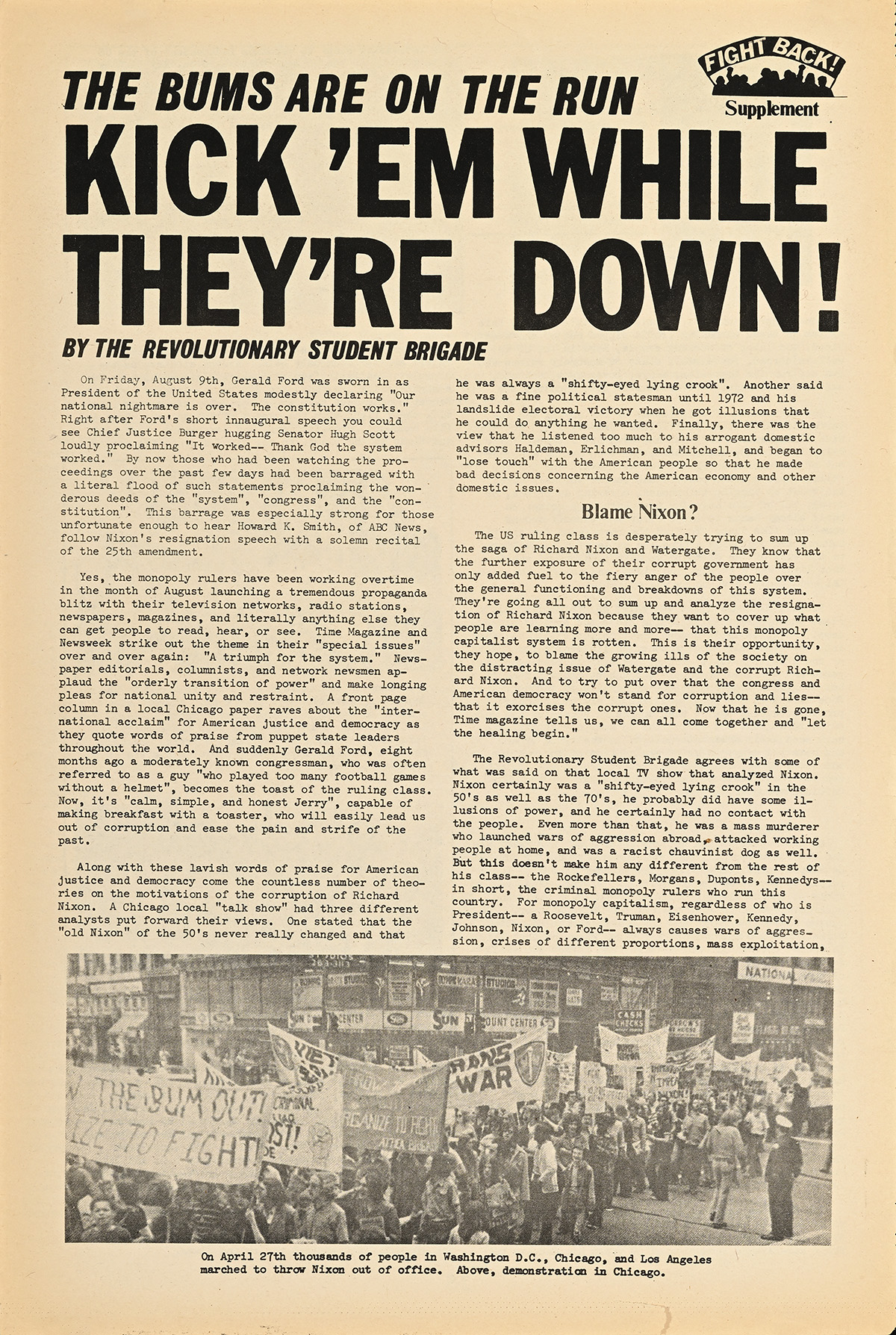

In the weeks and years that followed, these events galvanized activists and reformers—particularly student-led groups and socialist organizations—some of which channeled their fury and frustration into poster art that reflected the national passions provoked by the bloodshed. These posters advertised screenings of the eponymous 1974 documentary on Attica and rallied those sympathetic to the plight of the “Attica Brothers,” who were refused amnesty once the prison was reoccupied by law enforcement. They also helped to sustain public awareness of the prisoners’ position by linking the events of Attica to other social causes, ensuring that the legacies of the men who fought and died, as well as of those who survived the uprising, would not be forgotten.

Please be advised that this display includes images and references to racism and police brutality that some viewers might find disturbing.

Unless otherwise noted, all posters are part of the Poster House Permanent Collection.

Click this link for connections to issues of contemporary prison reform.

Large text is available at the Info Desk.

Guías con letra grande están disponibles en informaciones.