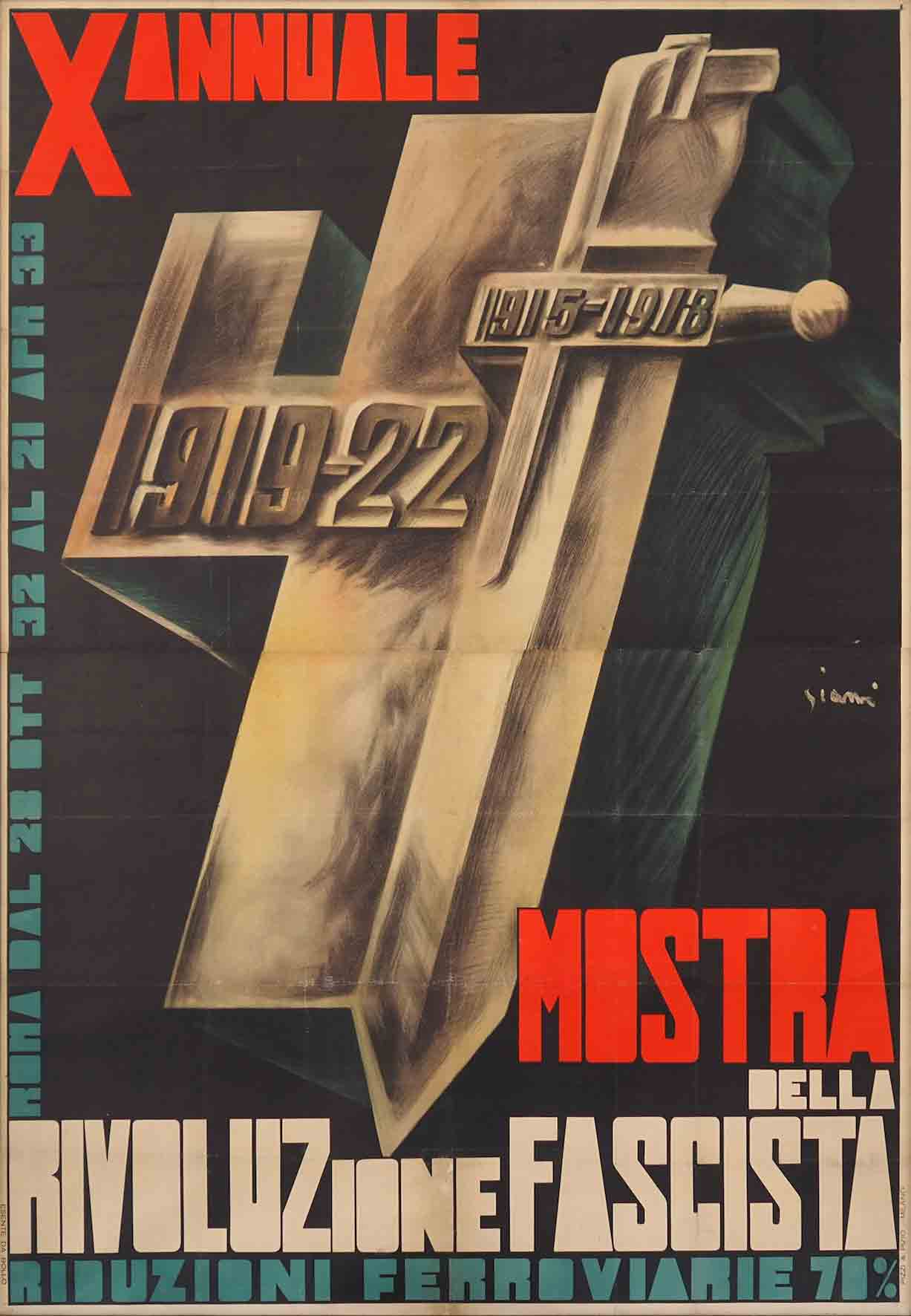

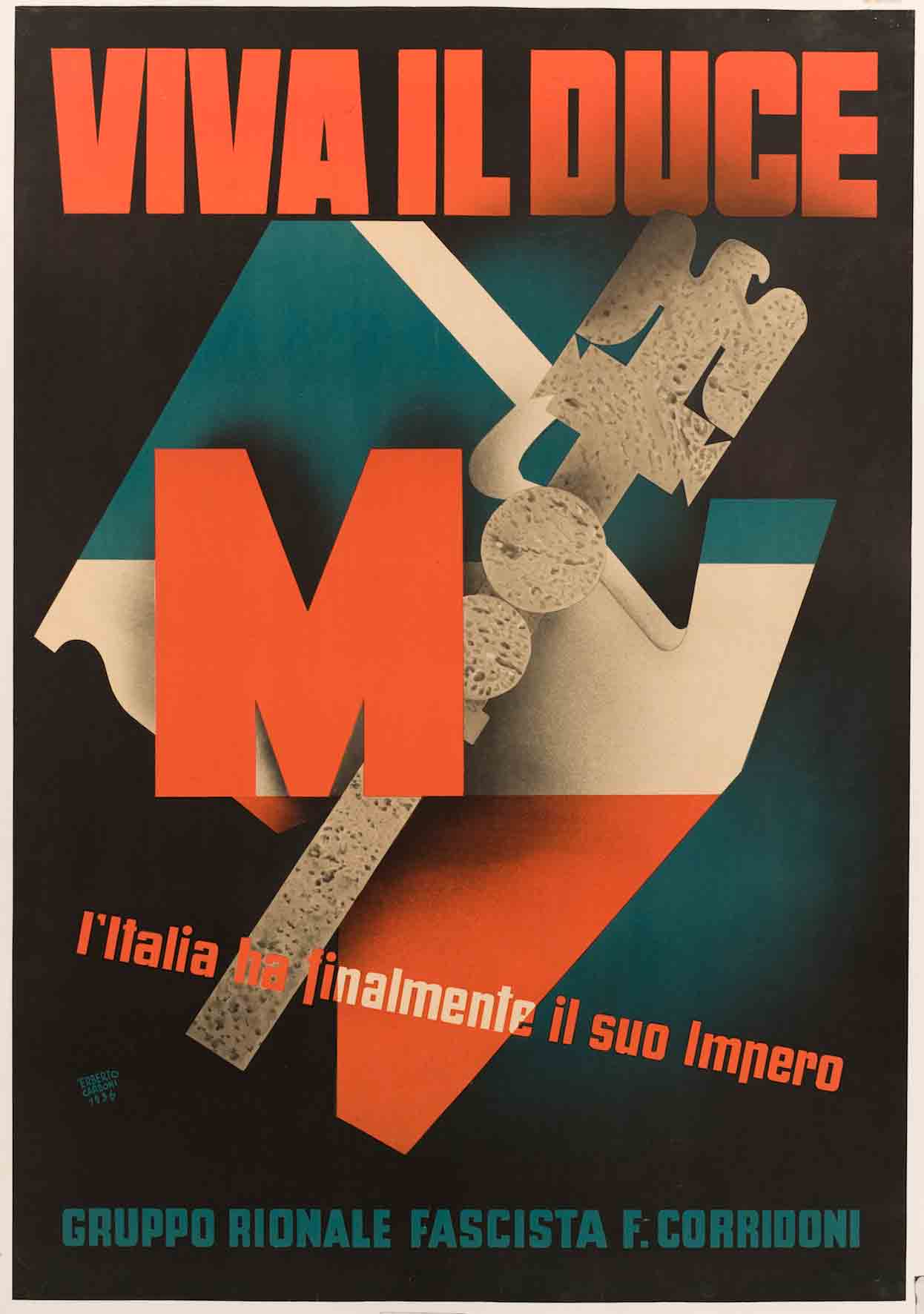

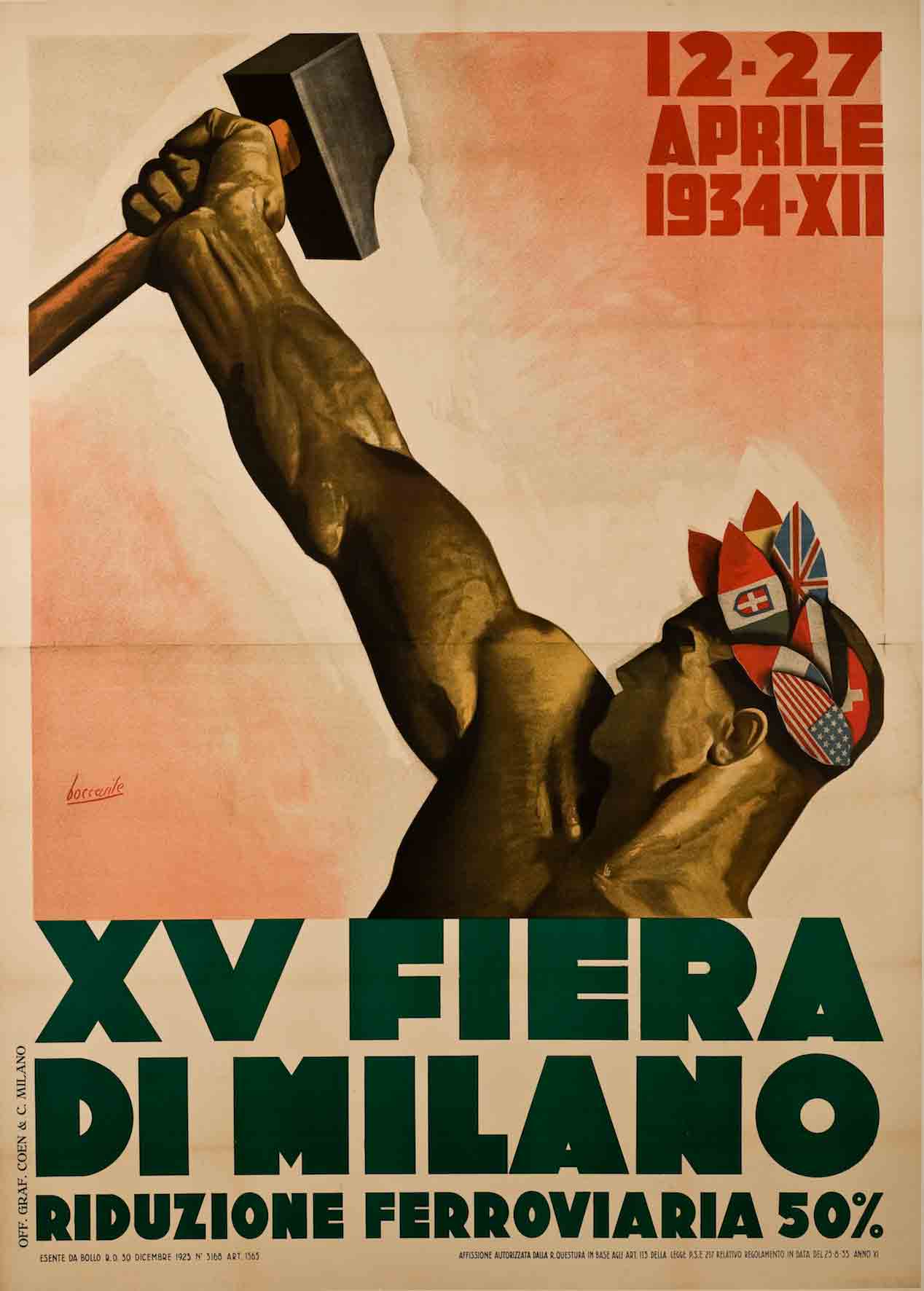

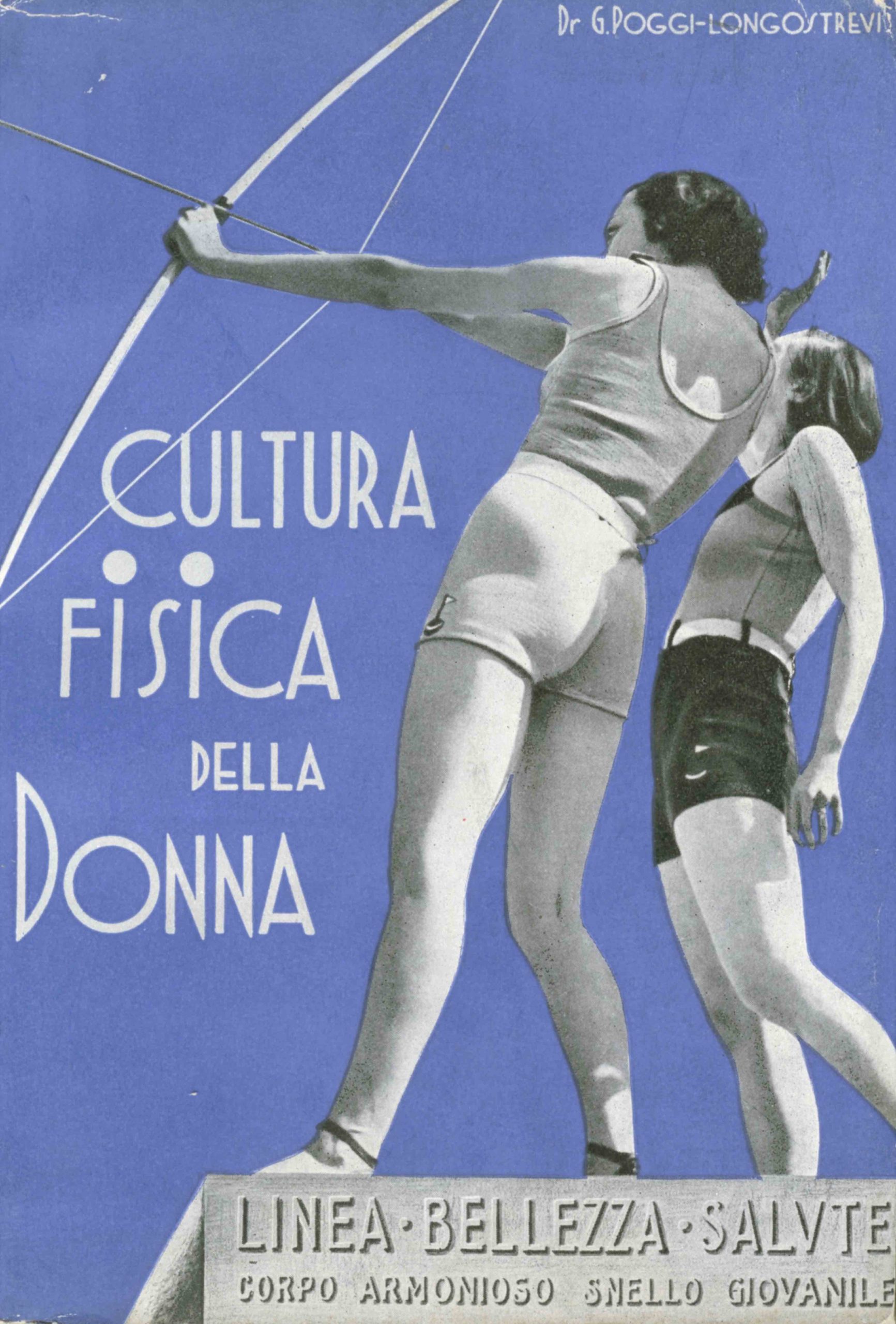

The Future Was Then: The Changing Face of Fascist Italy

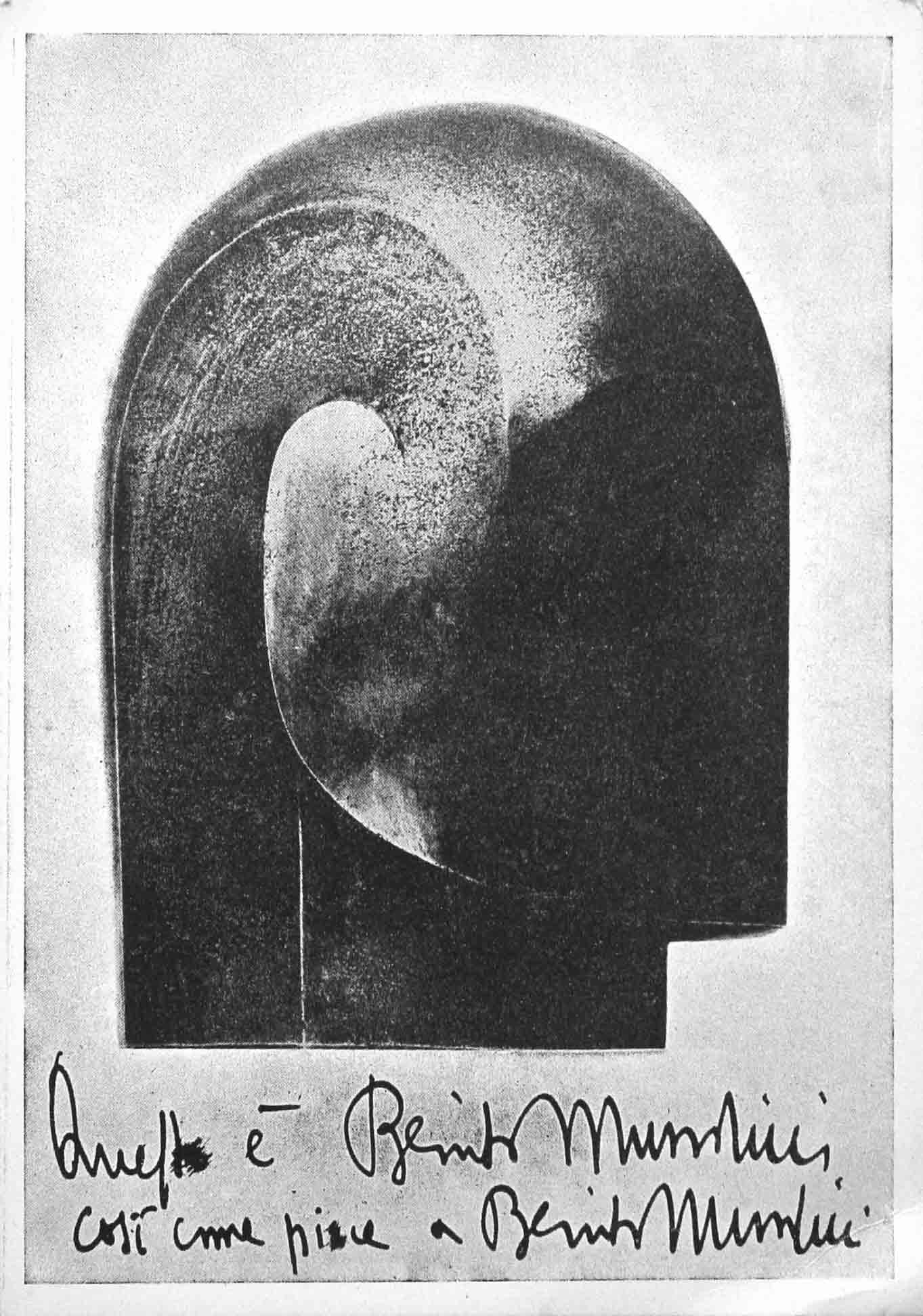

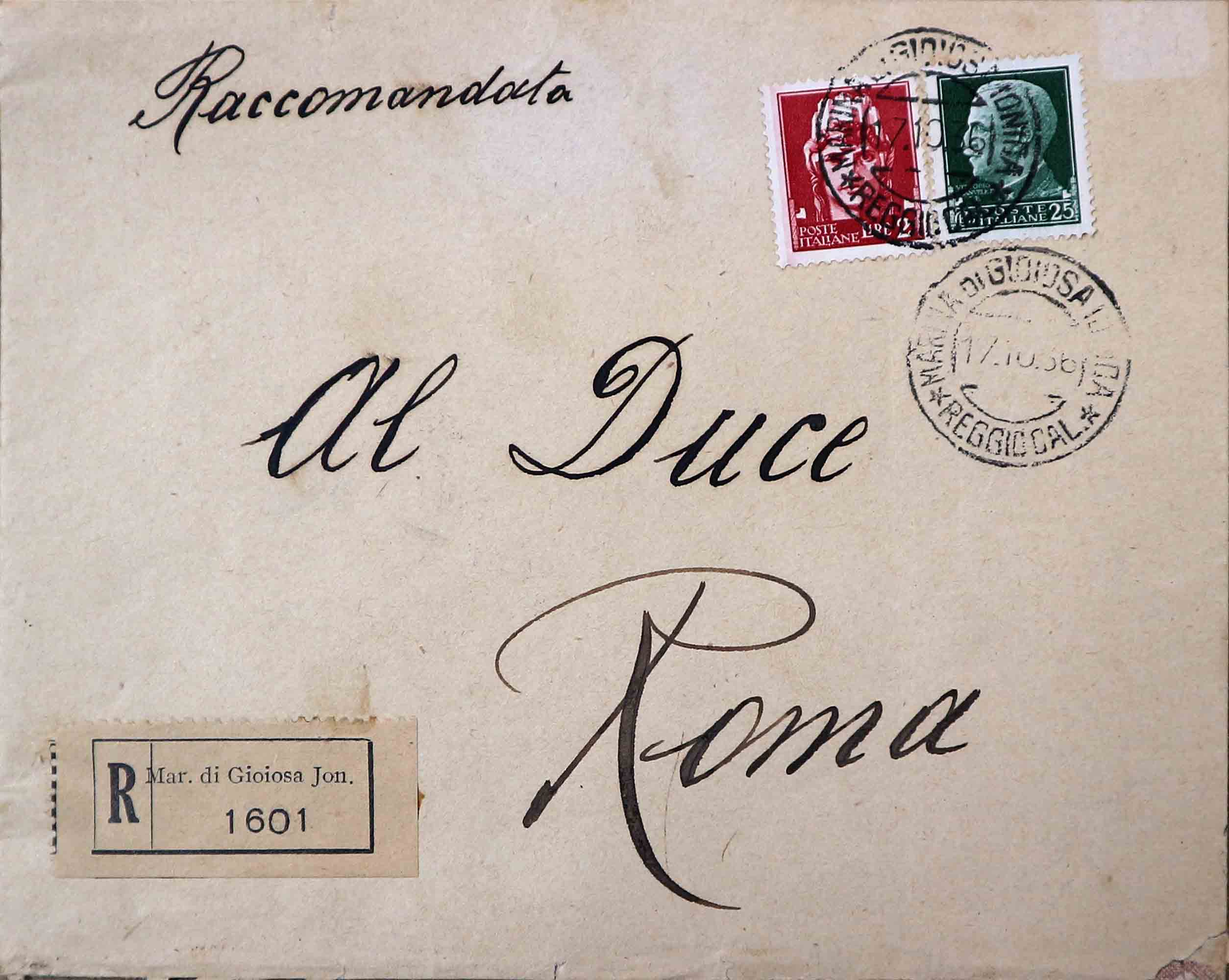

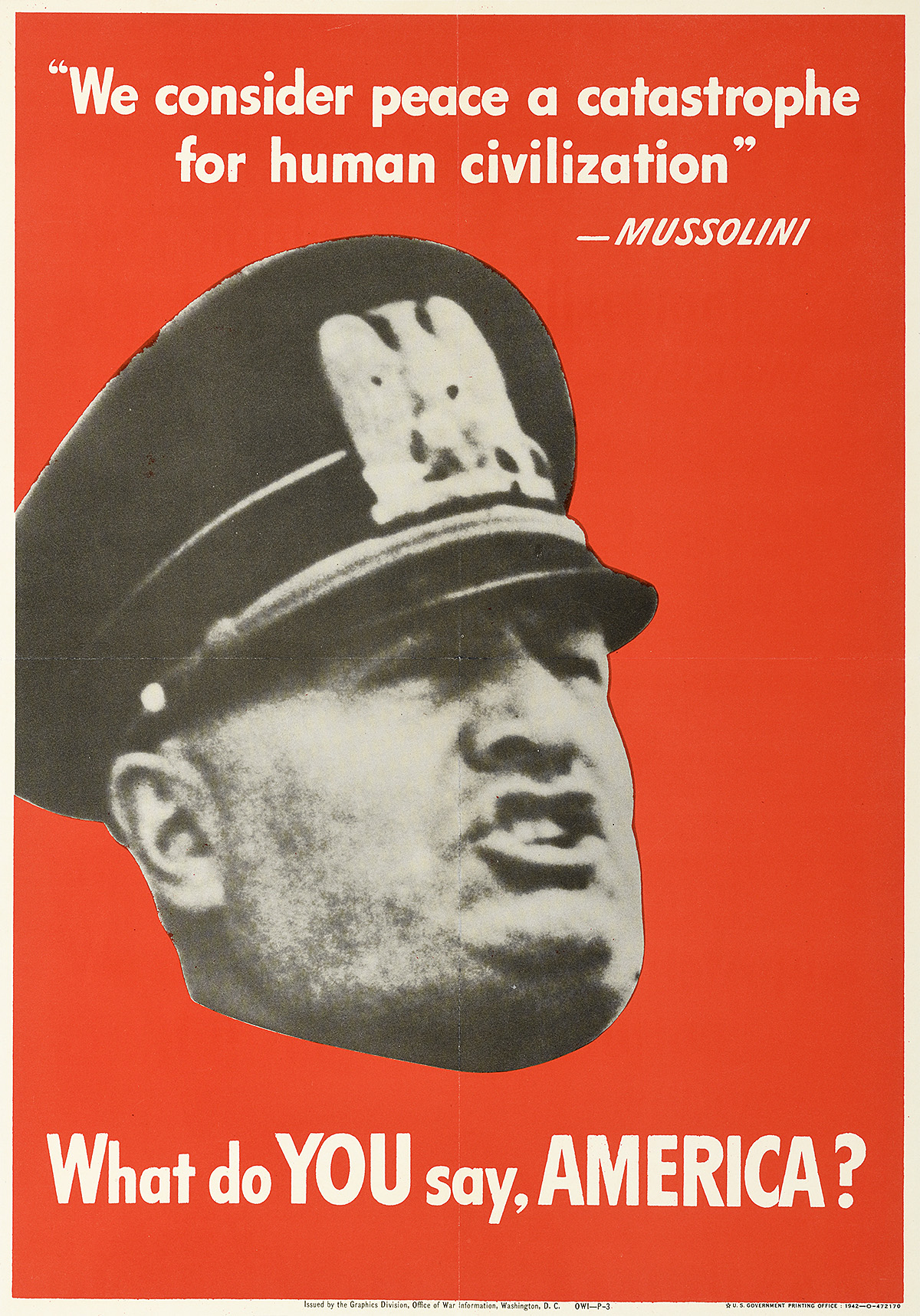

In early 1918, a little-known, largely unimportant Northern Italian writer and bureaucrat penned a newspaper editorial calling for the emergence of “a man ruthless and energetic enough to make a clean sweep” to revive the Italian nation. During a speech in Bologna three months later, he suggested he might be the very person for whom he had pressed; four years later, he led a march on Rome to prove that, in fact, he was.

His name was Benito Mussolini.

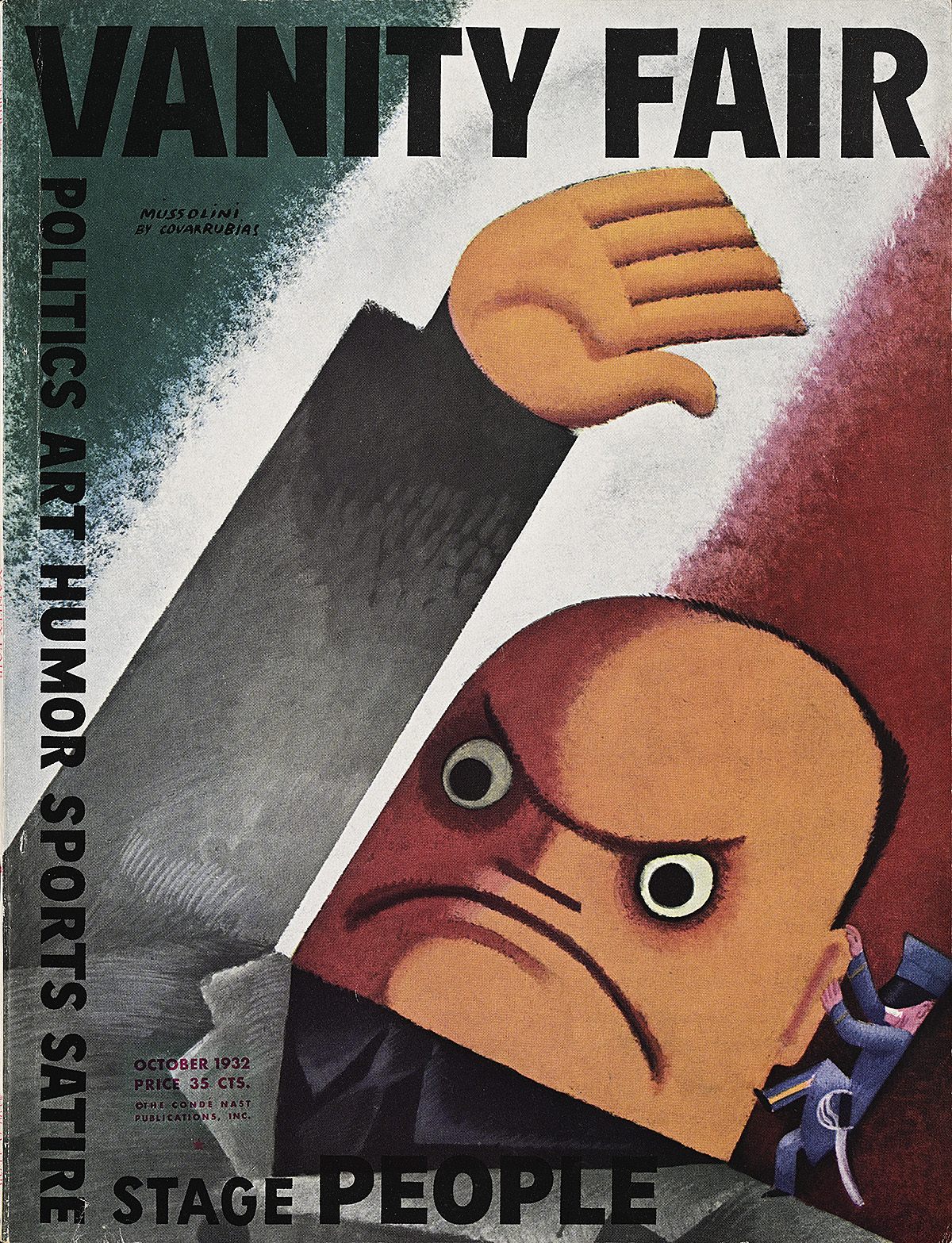

In the aftermath of World War I, the Italian peninsula was not what it once was: the home of the Roman Empire—perhaps the most powerful the world had ever known—and of the Renaissance, when culture and art had flourished, and tremendous wealth had been amassed. Italy had since sunk to a place among Europe’s poorest nations, and its people were disaffected and disunified. In the first two decades of the 20th century, it had been dragged through a global war, a devastating pandemic, large-scale emigration, food shortages, and rapid inflation. Mussolini, a former schoolteacher and soldier, gradually built a cult of personality around his reputation as a populist, purposefully buffoonish bully, and earned the support of an unusual coalition between the nation’s industrial elites, who saw opportunity, and its rural poor, who saw him as one of their own. In 1922, he gathered thirty thousand thugs in black shirts at the capital, raising one-armed “Roman salutes” to demand the resignation of the sitting prime minister. Italy’s figurehead king, Victor Emmanuel III, feared violence and quickly handed power

to the young radical.

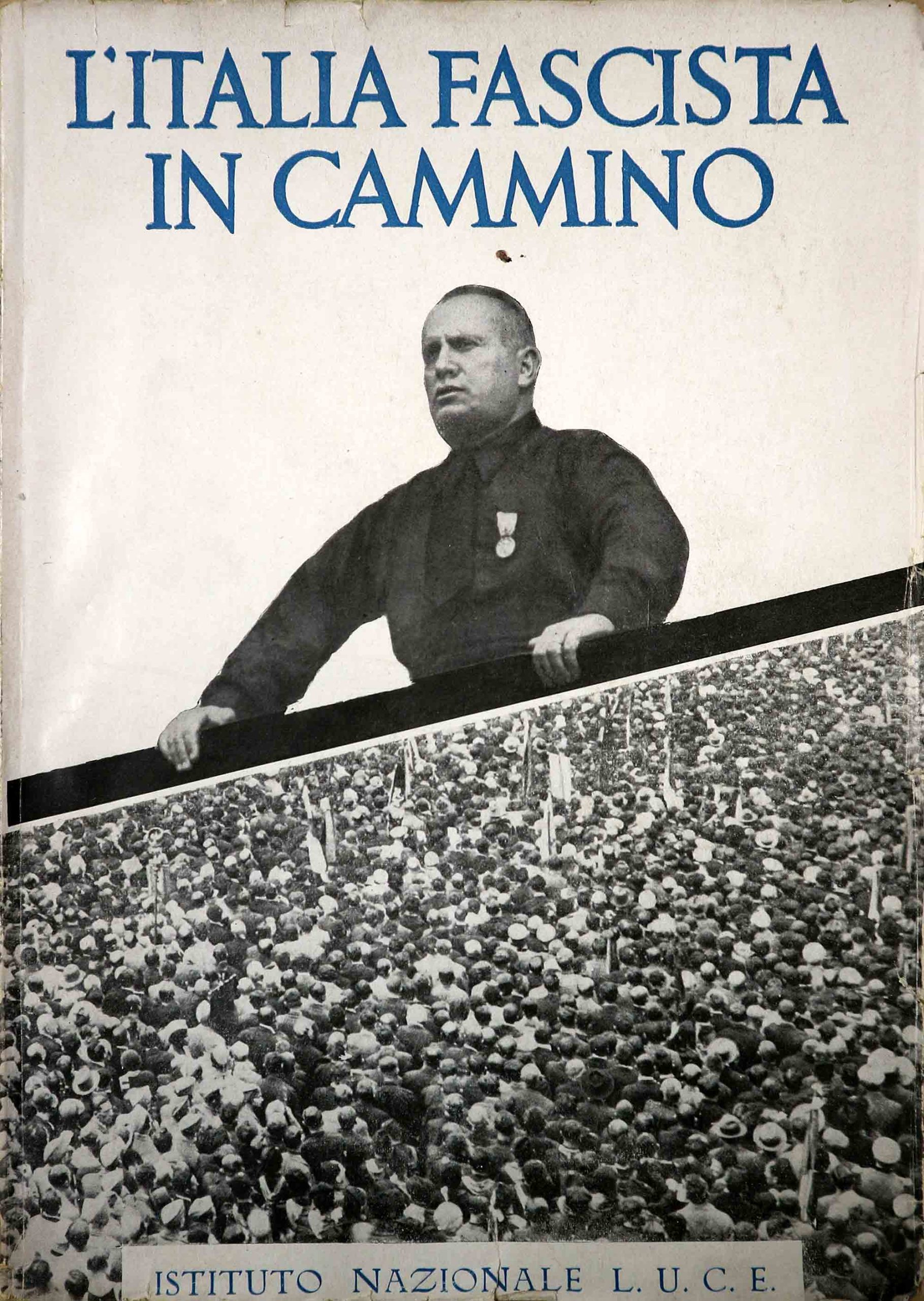

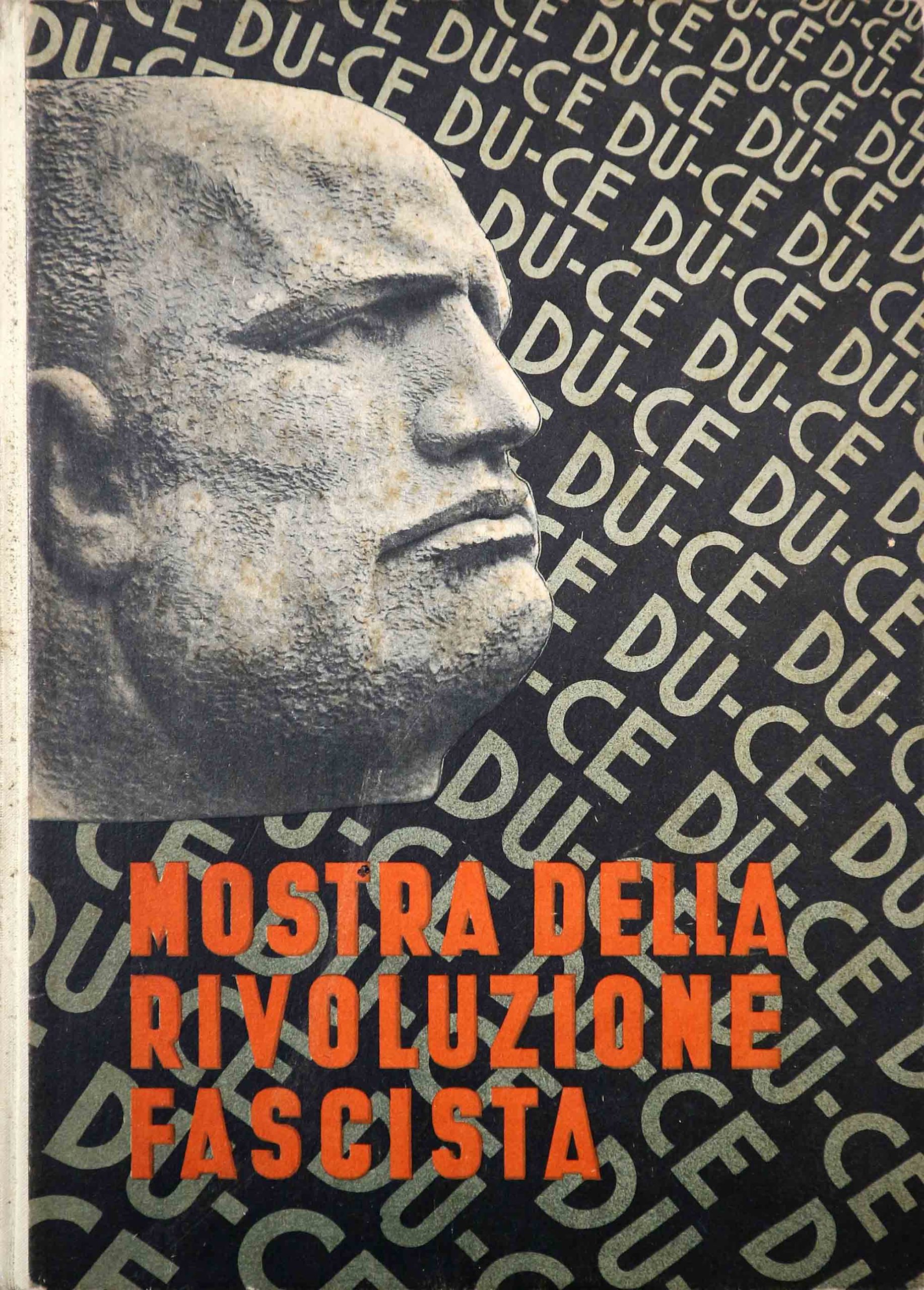

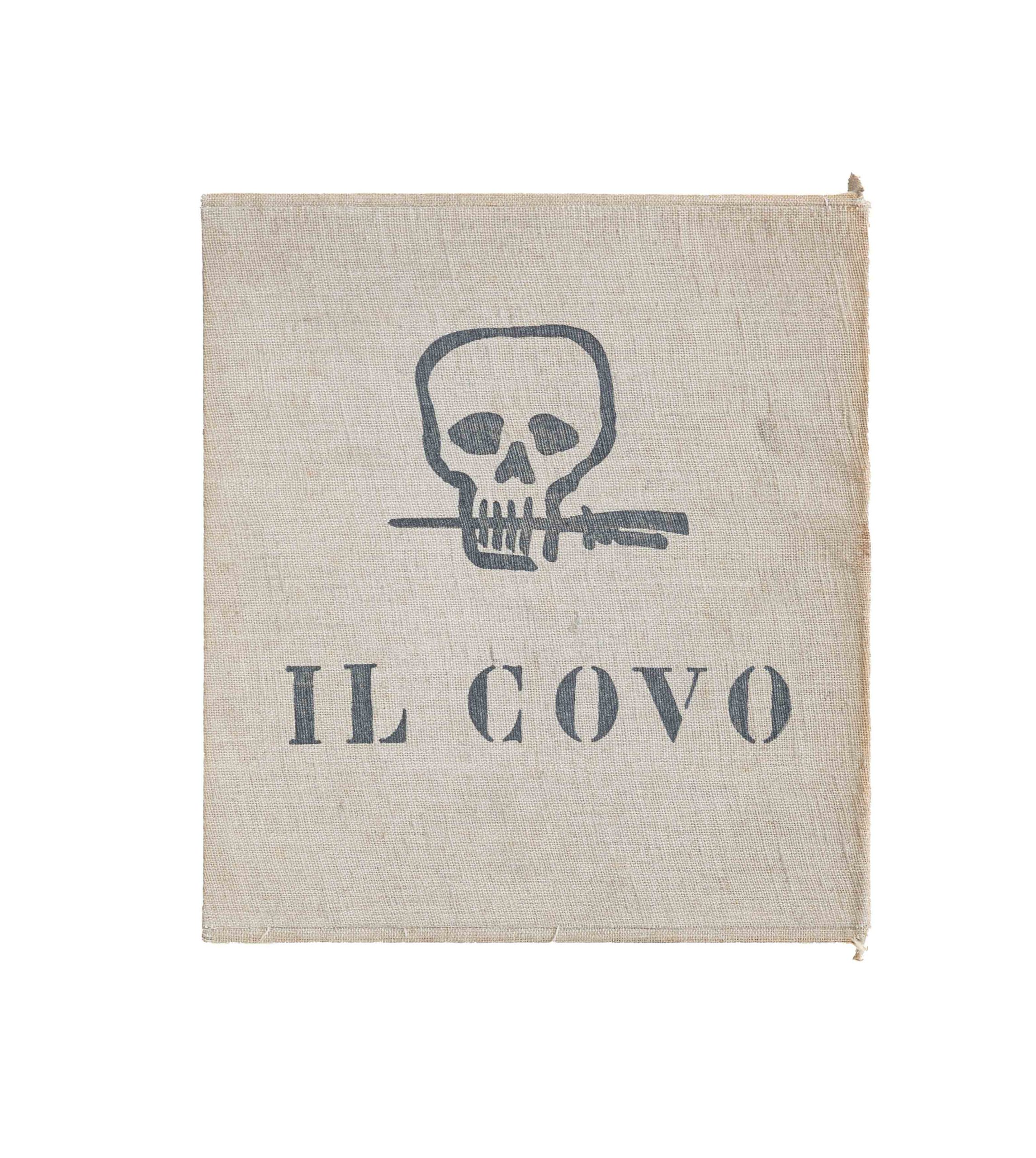

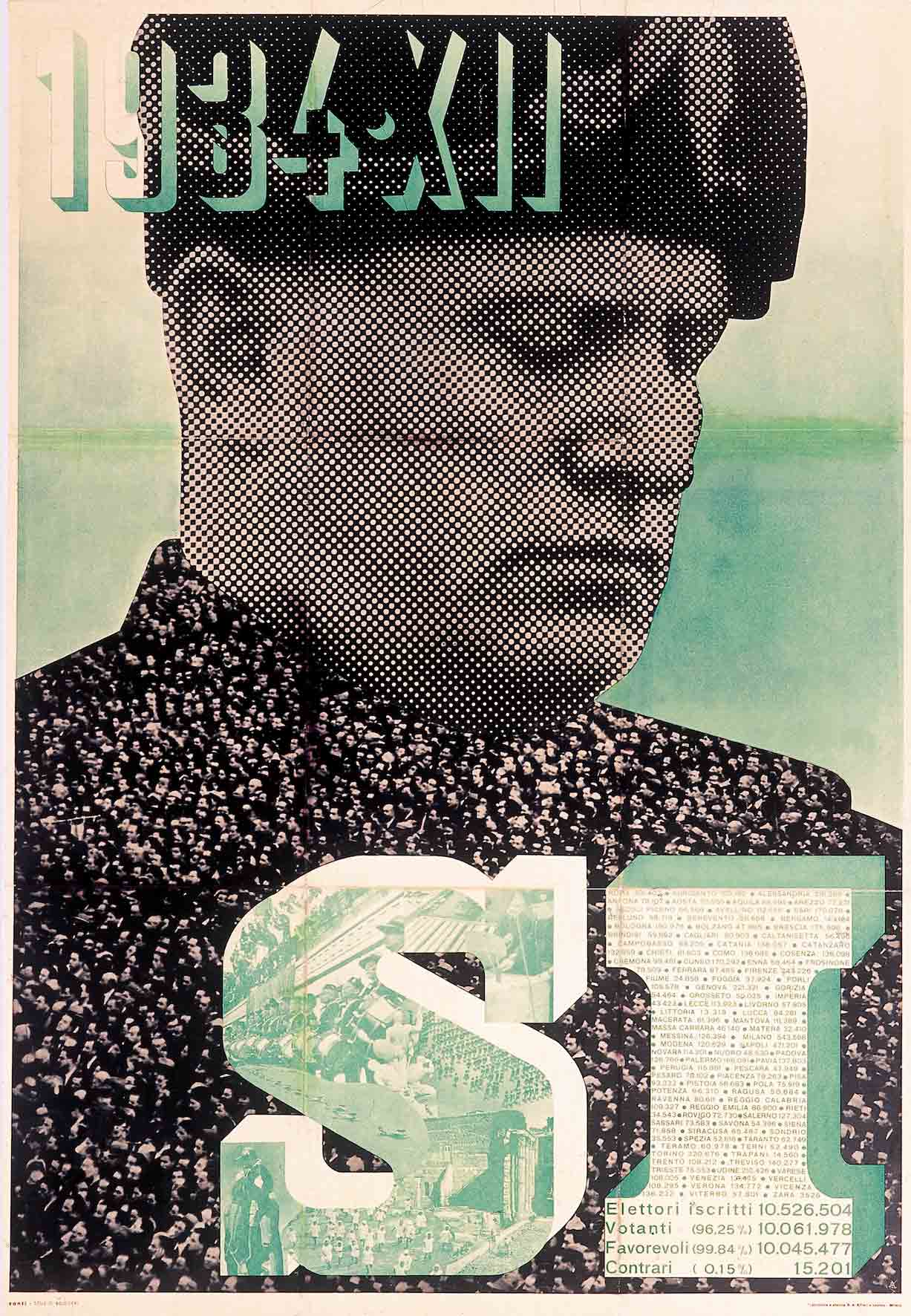

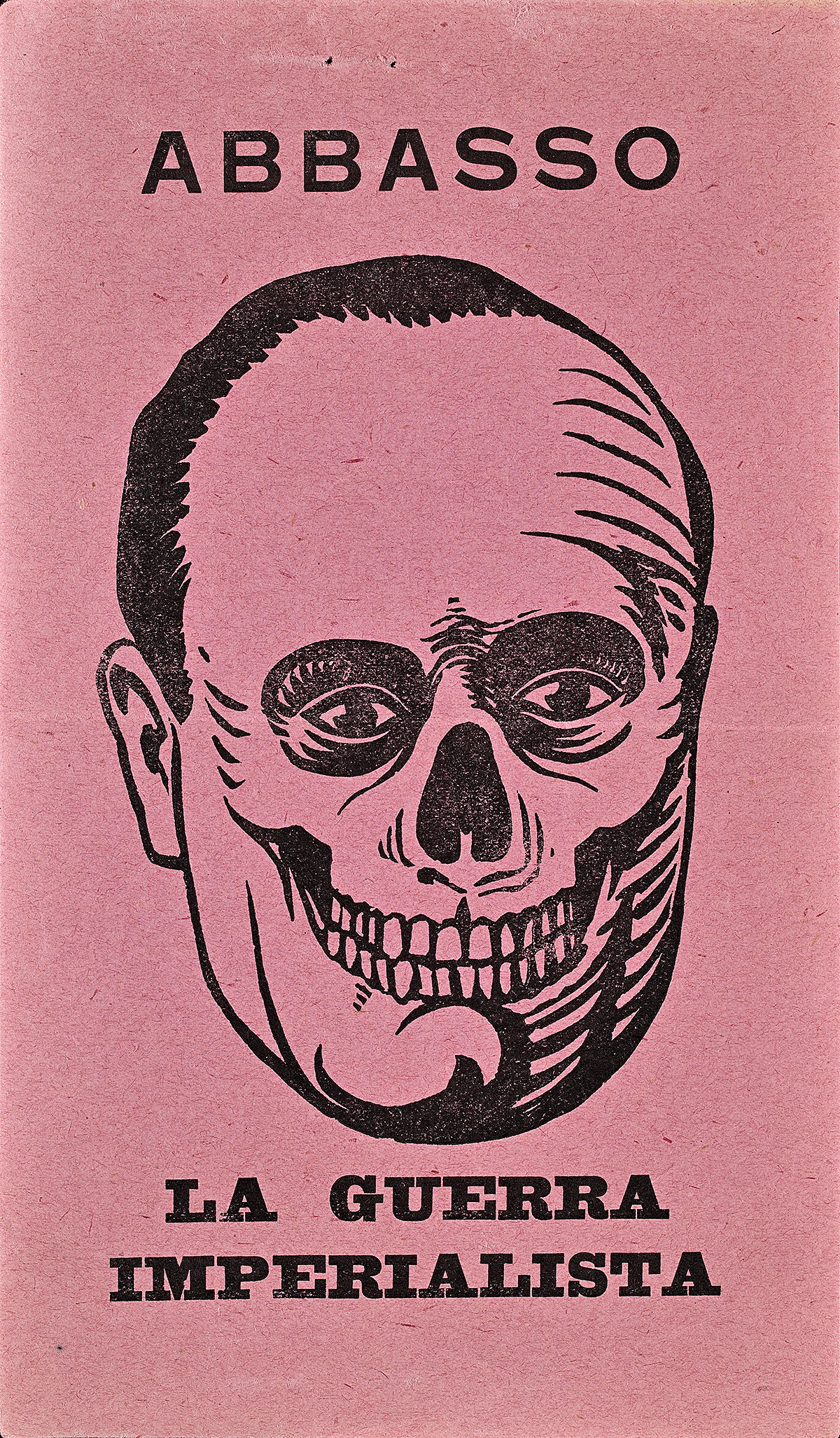

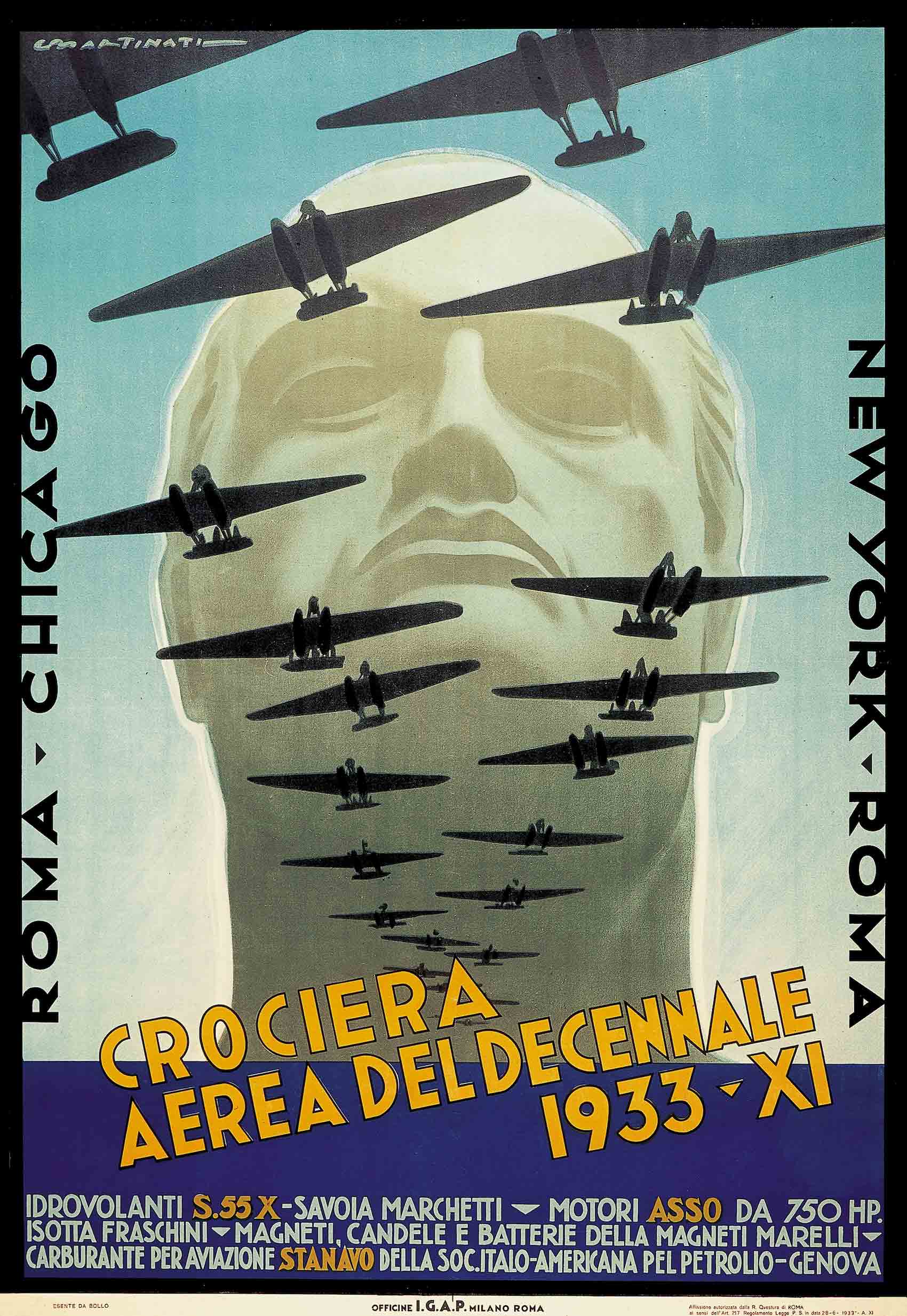

Mussolini seized power without being elected; he ruled without morality. He controlled every branch and office of his nation’s government, and vowed to rule without any checks or balances, claiming he would restore law and order. The king, and many Italians, believed him.

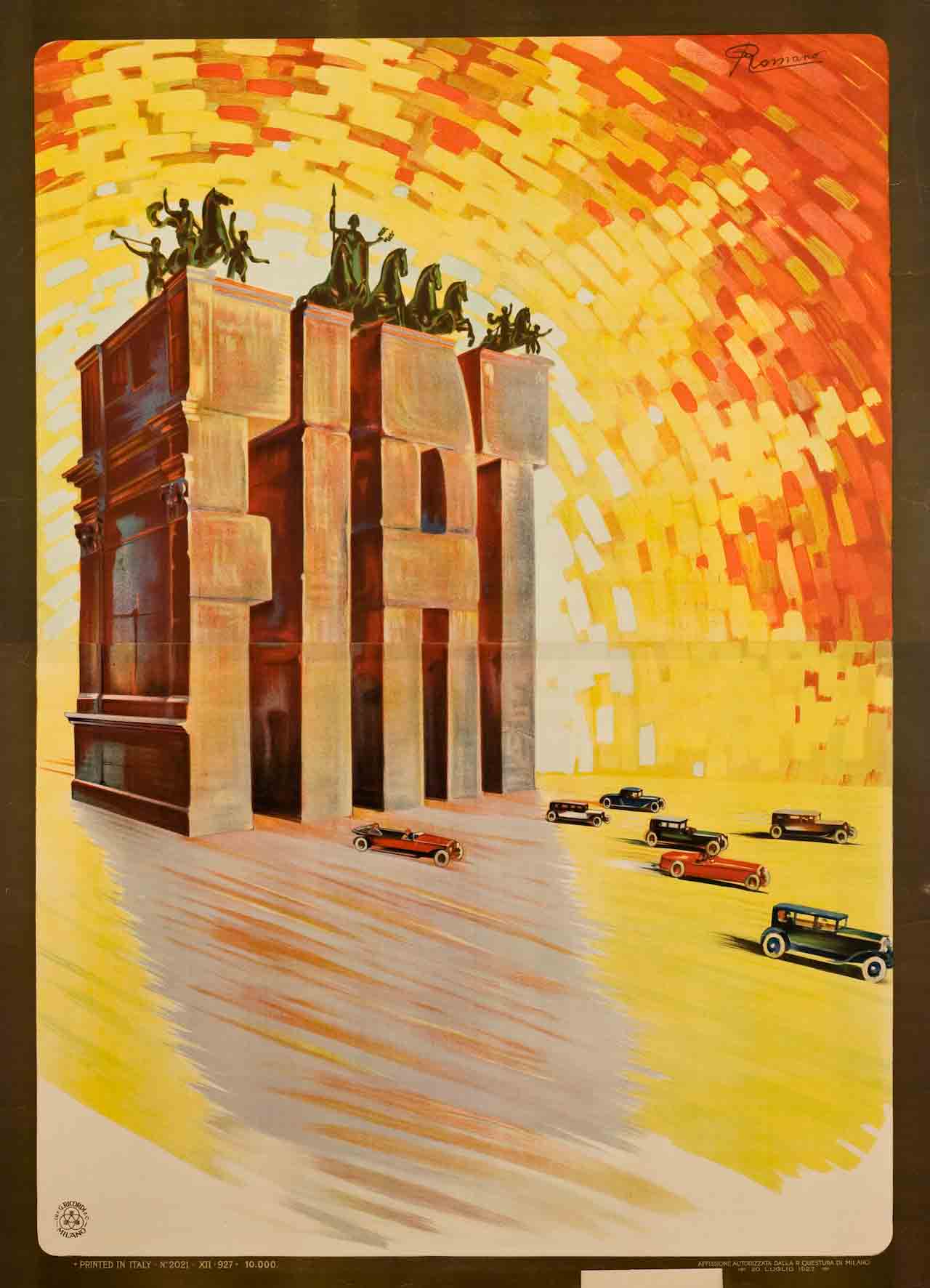

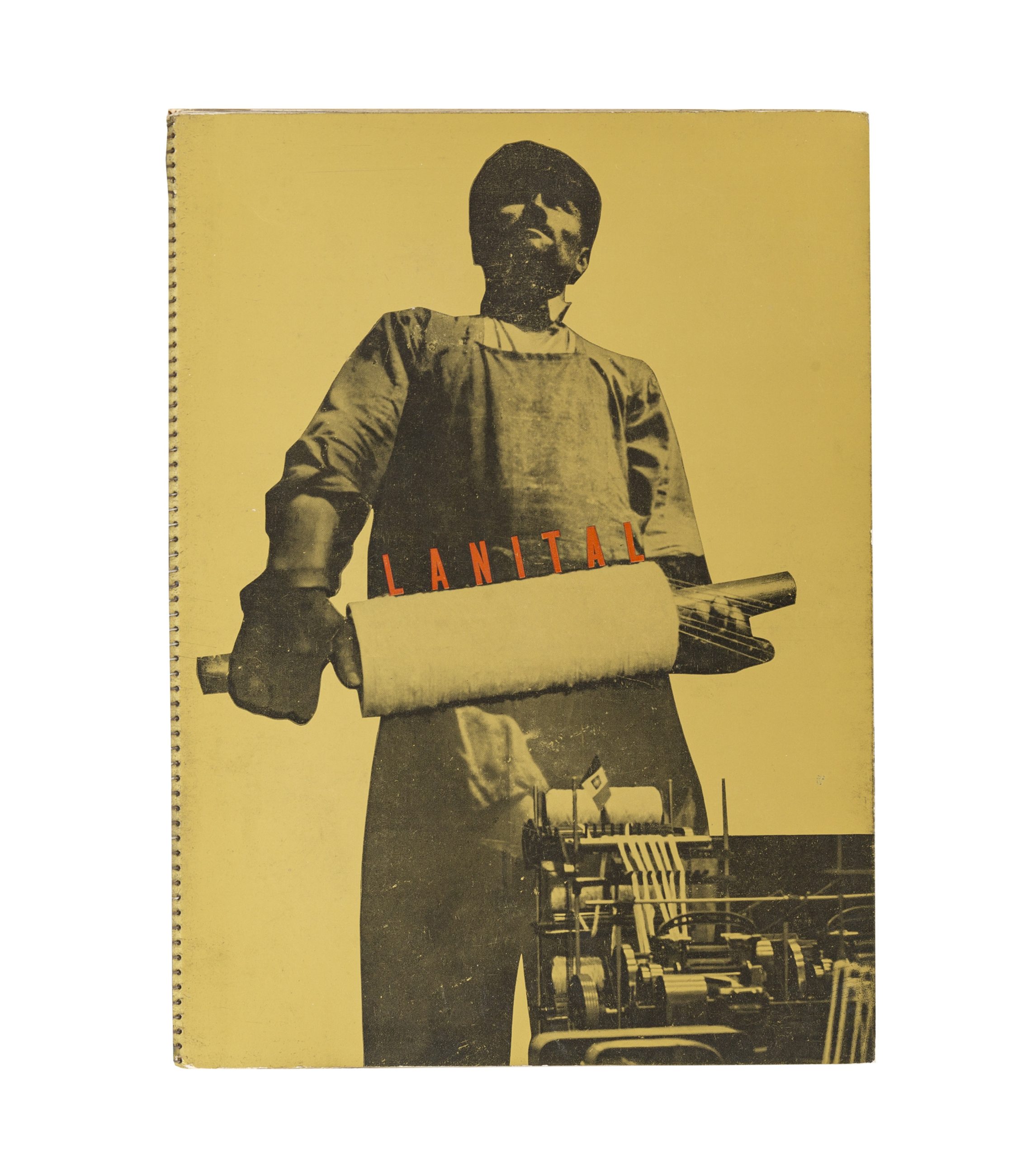

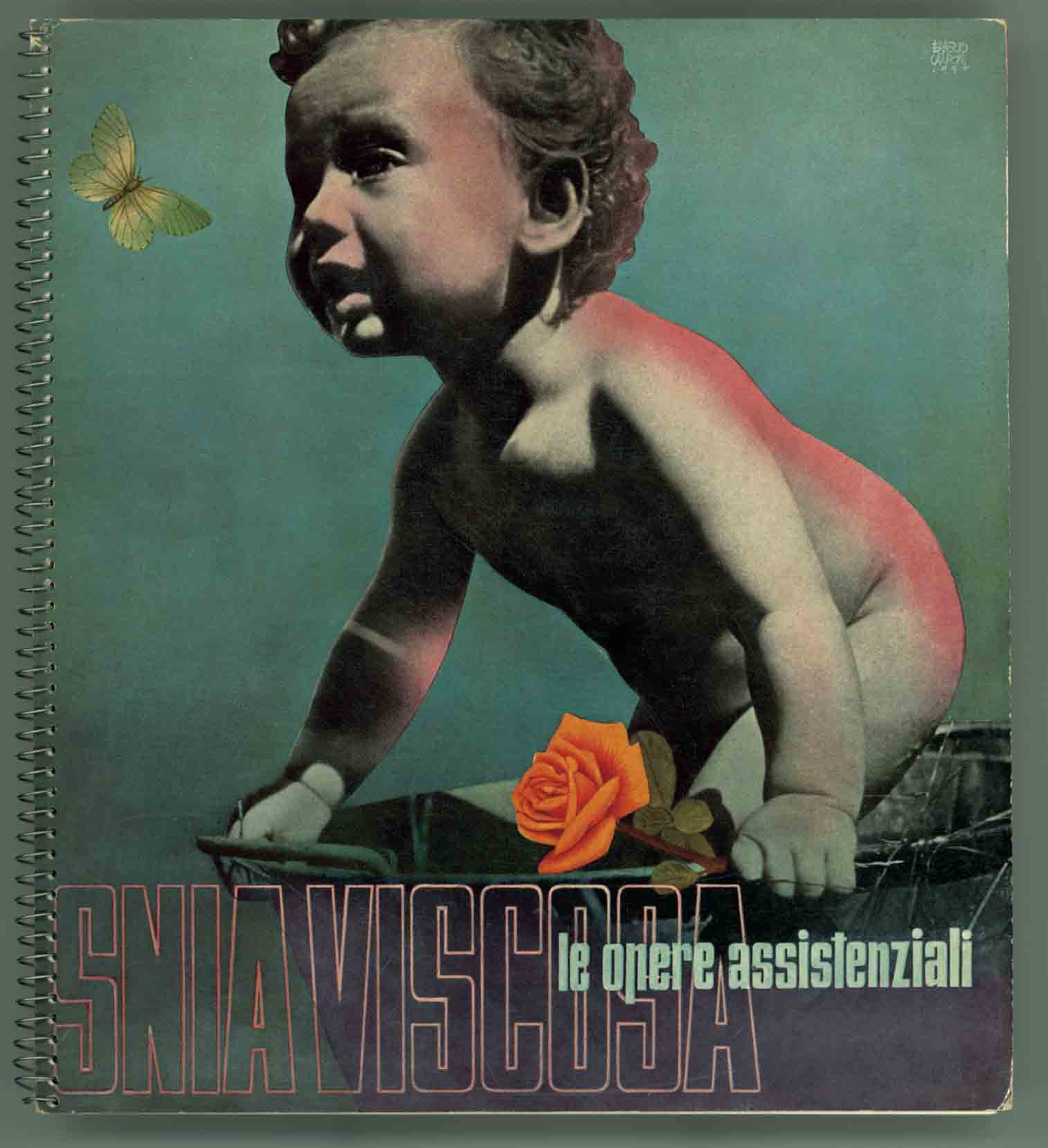

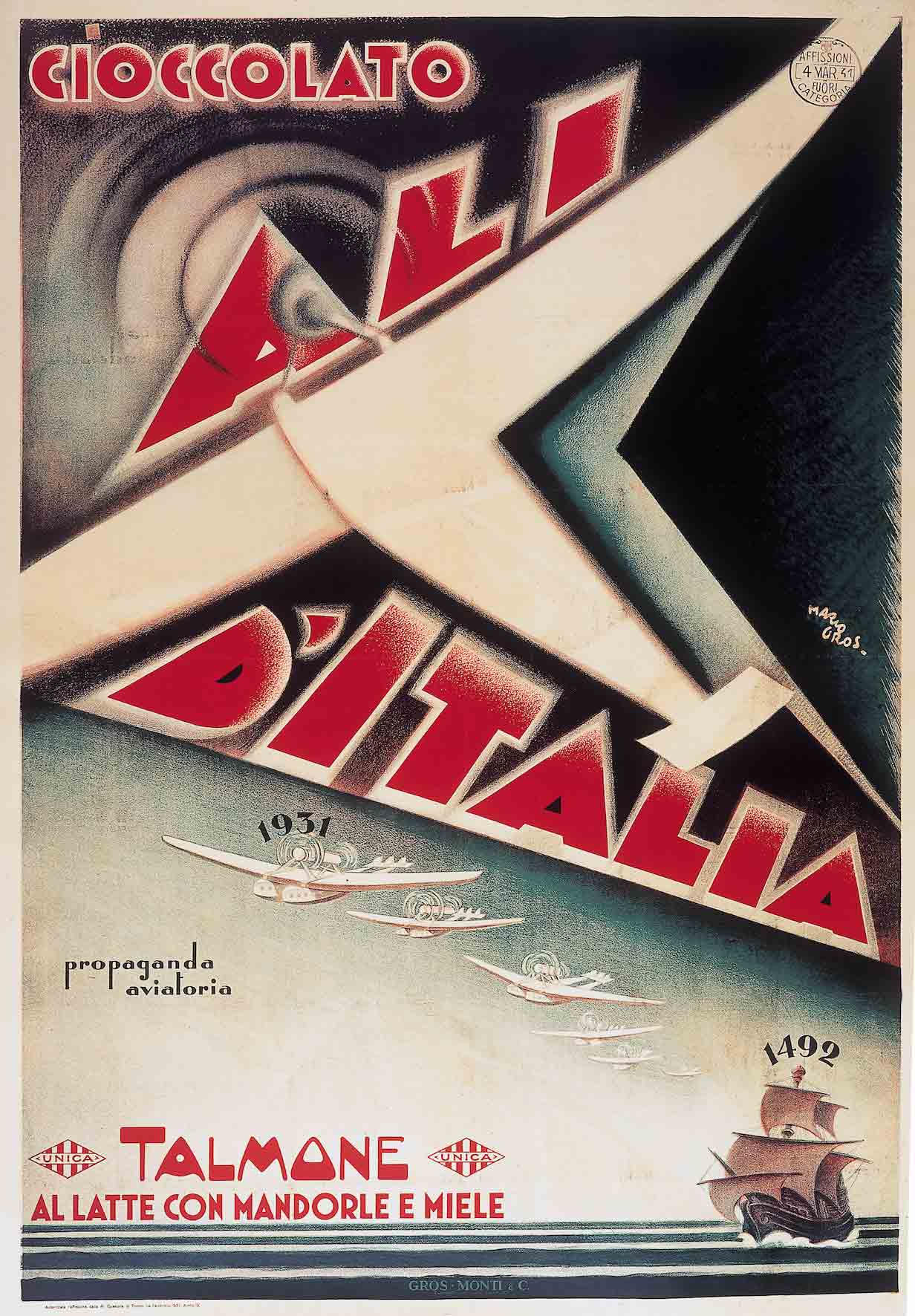

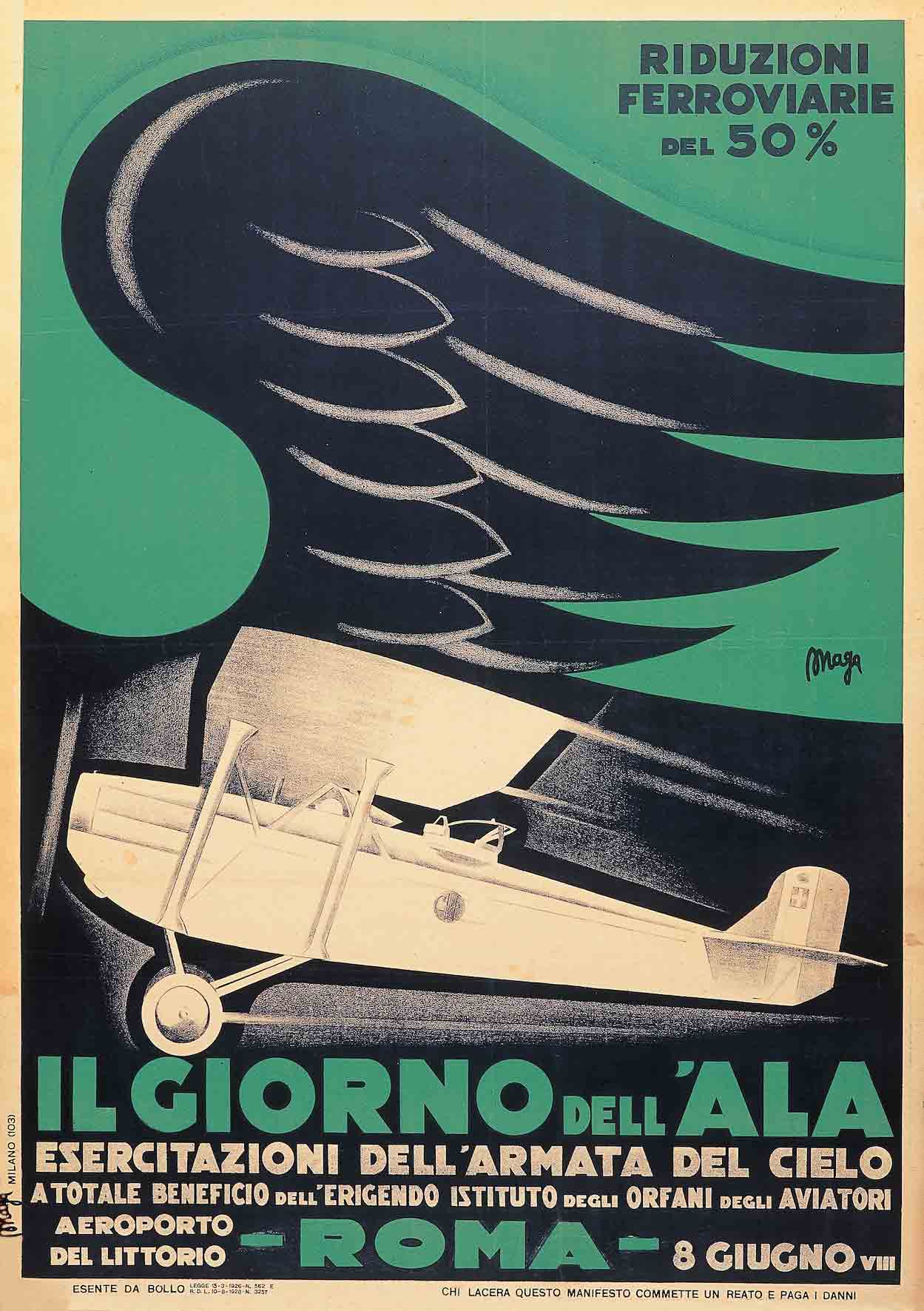

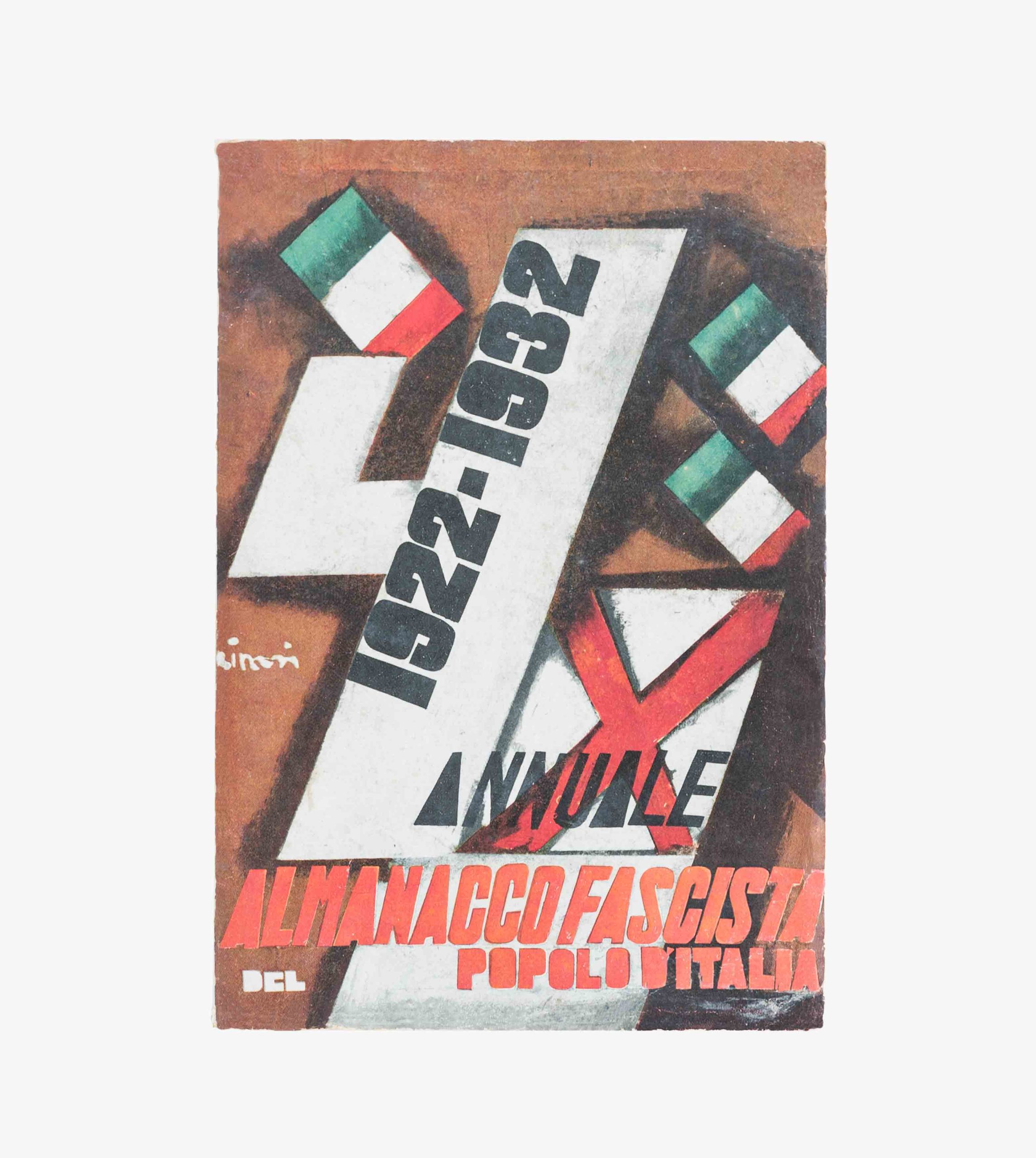

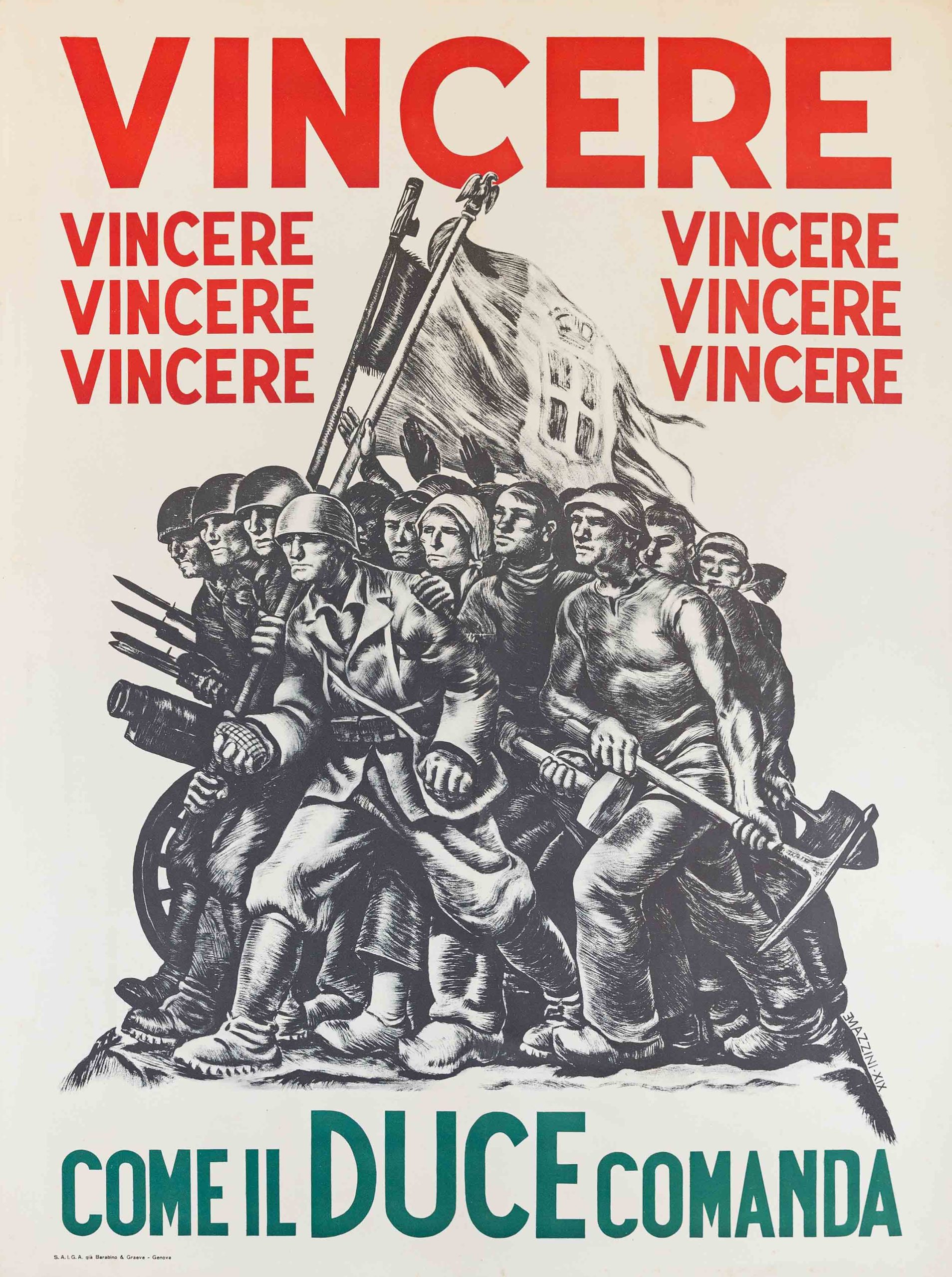

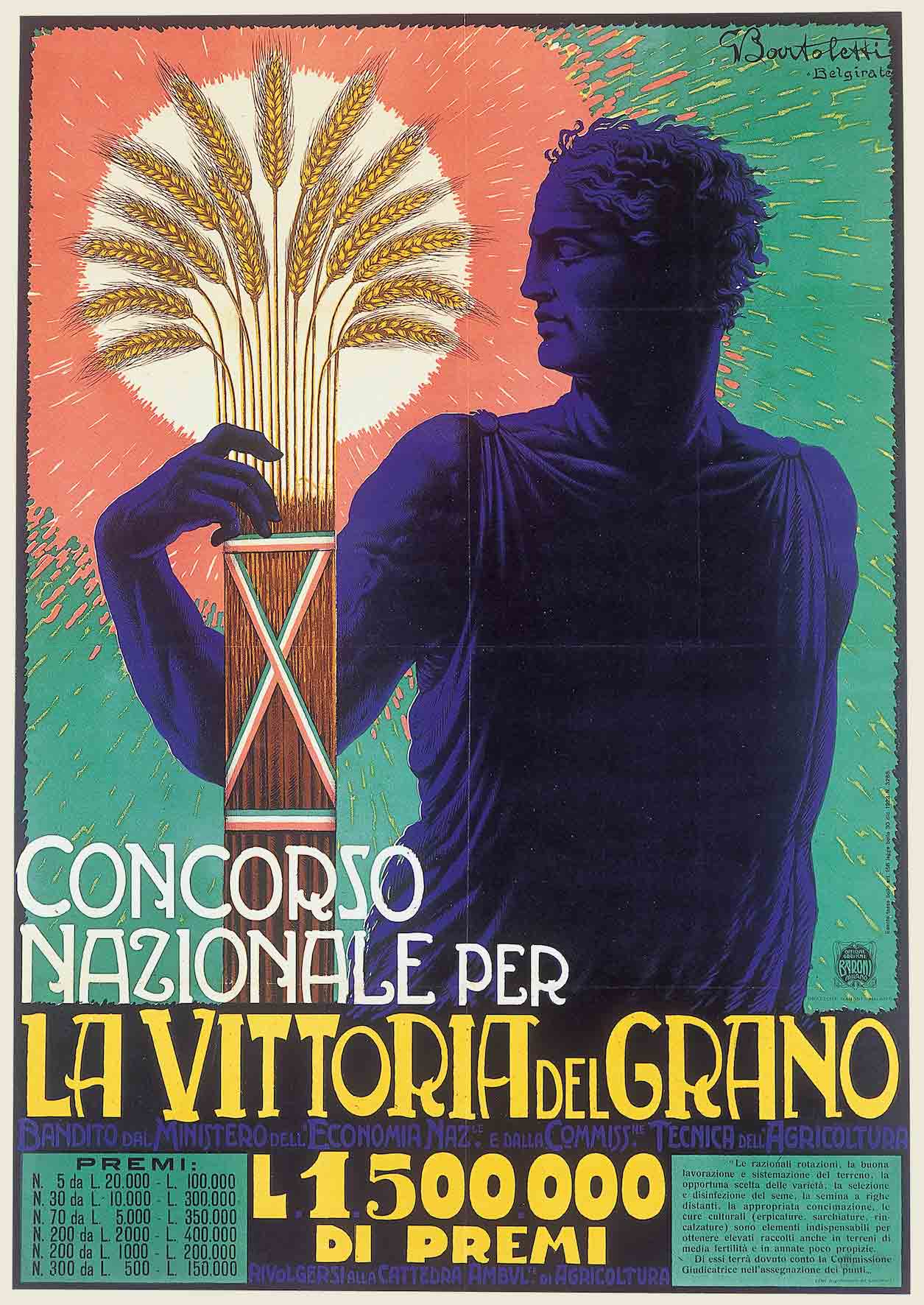

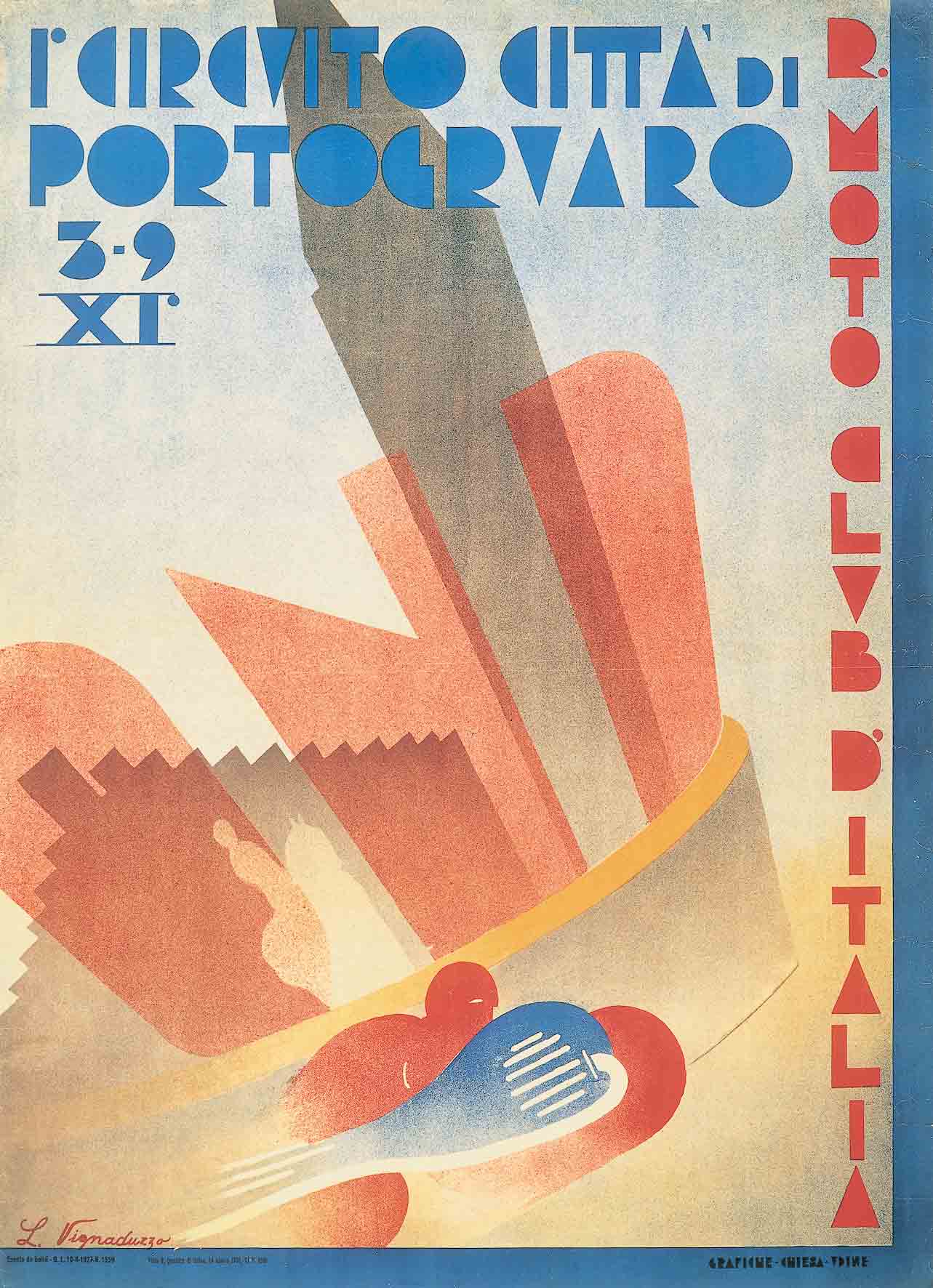

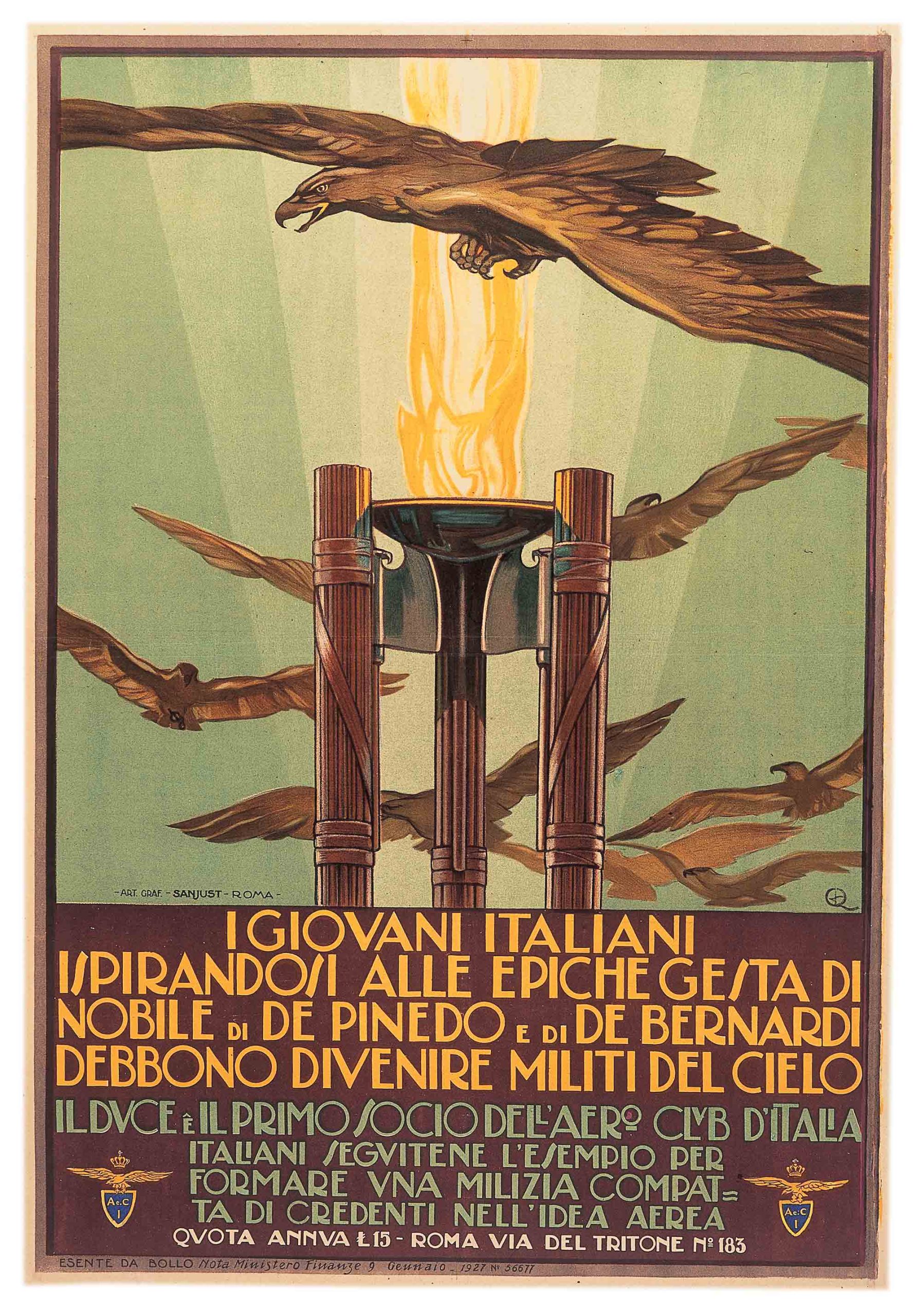

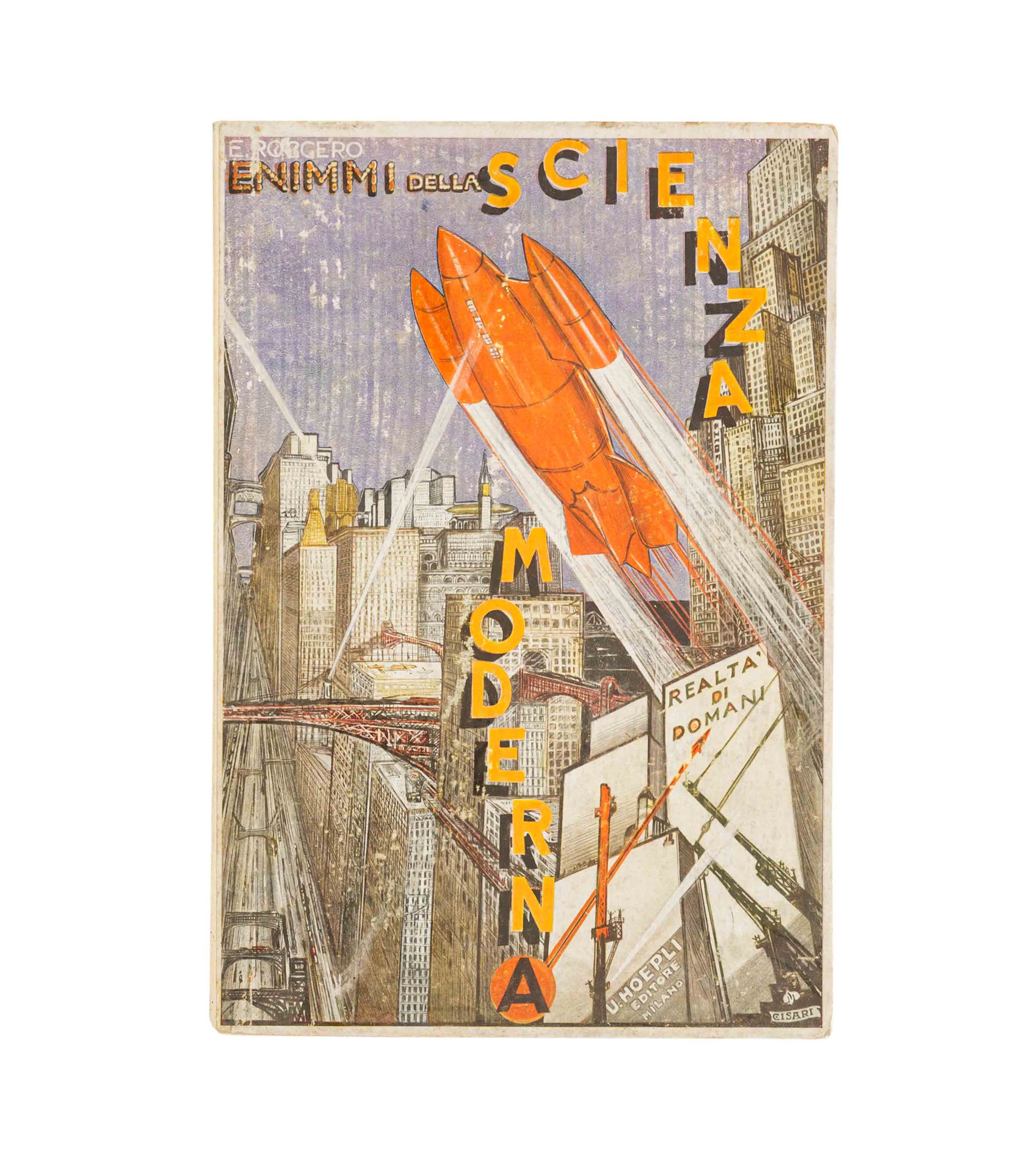

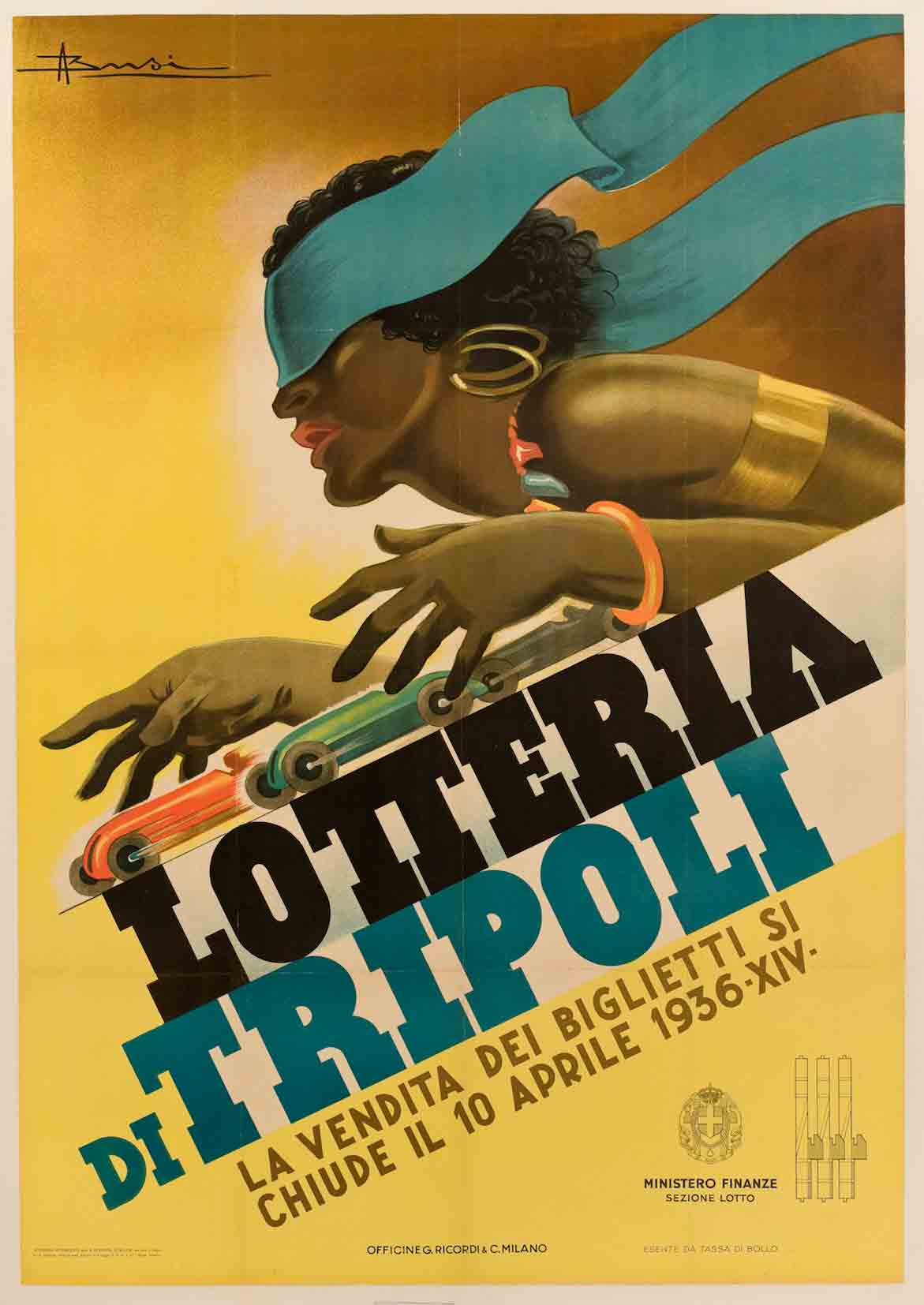

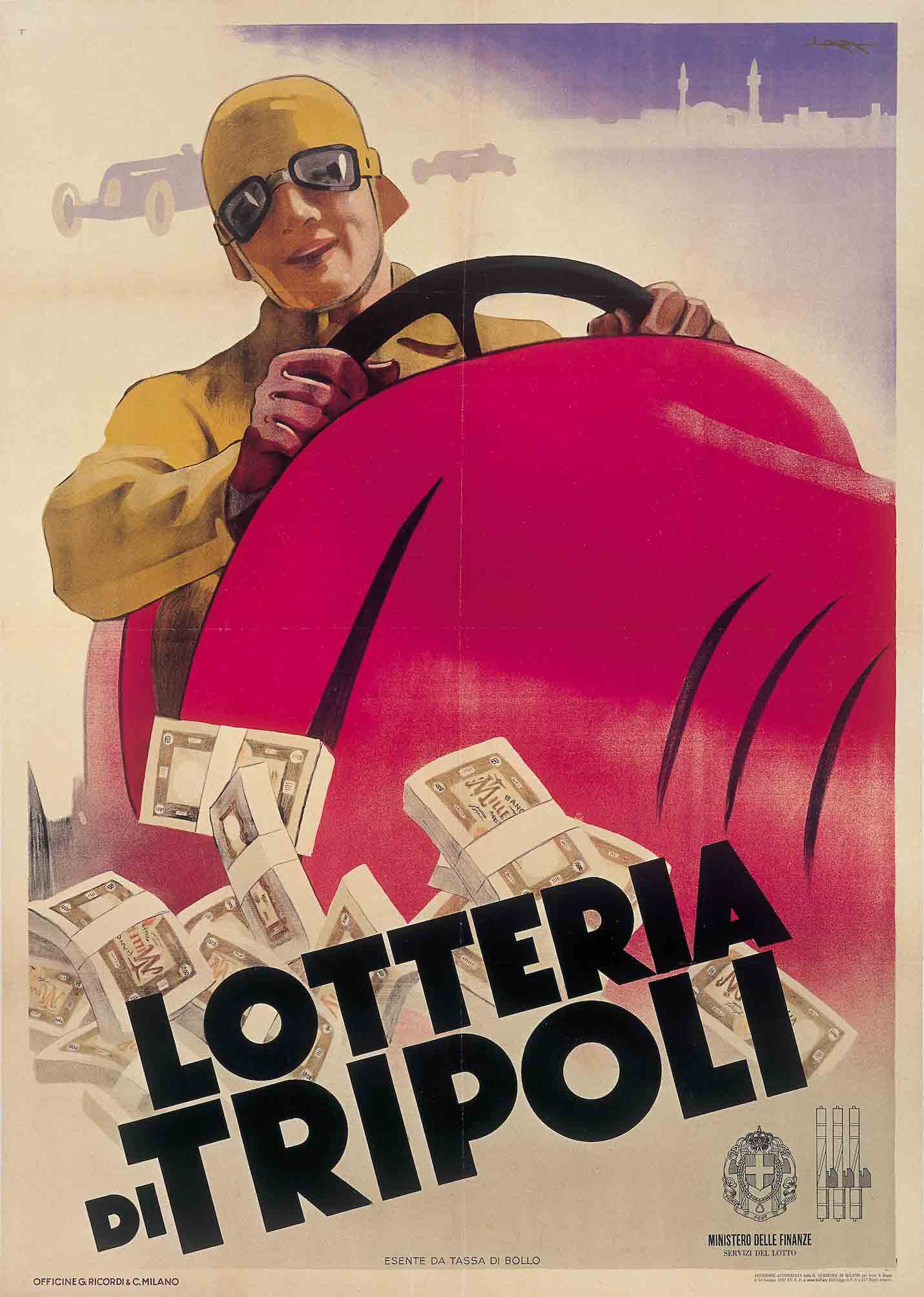

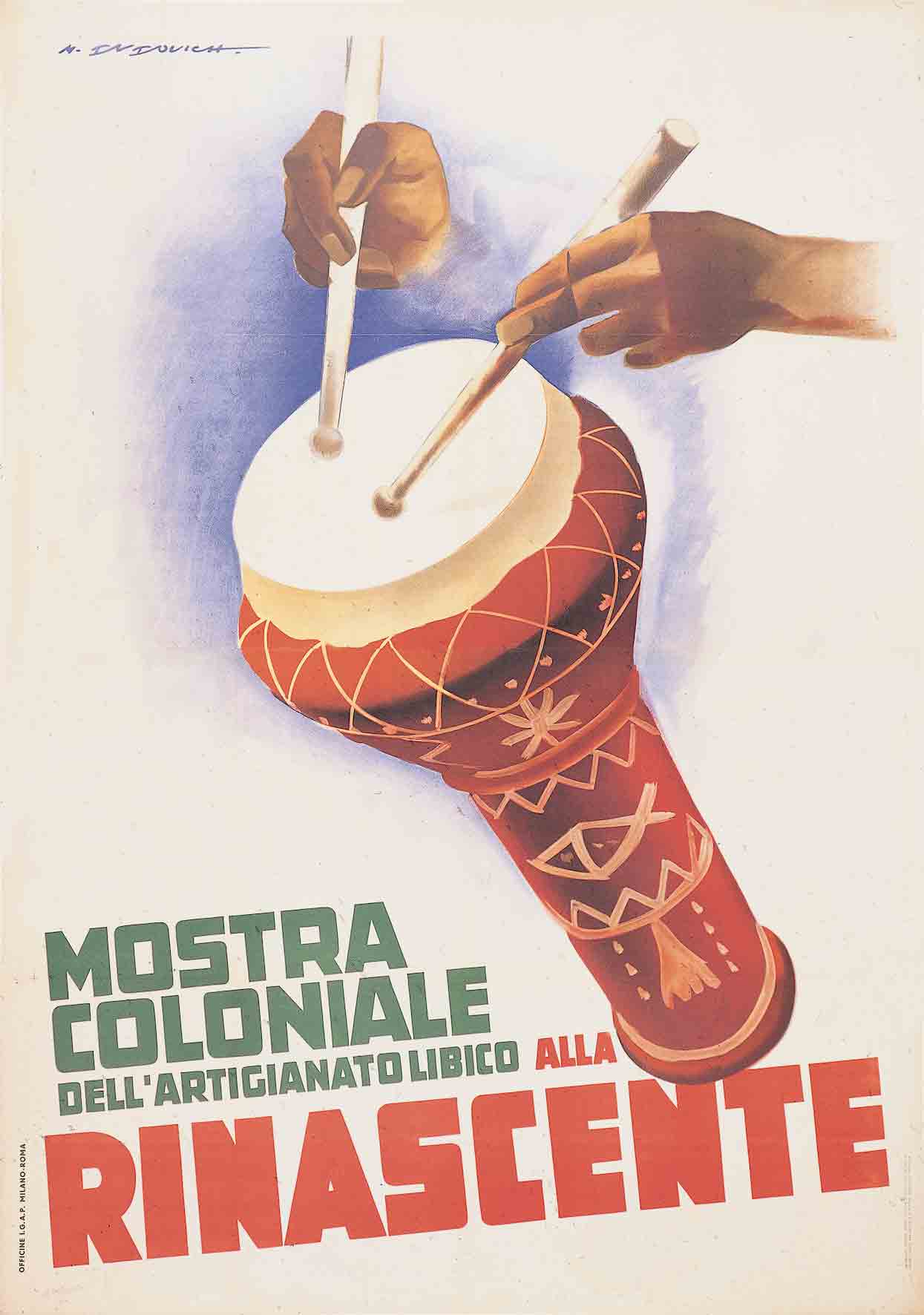

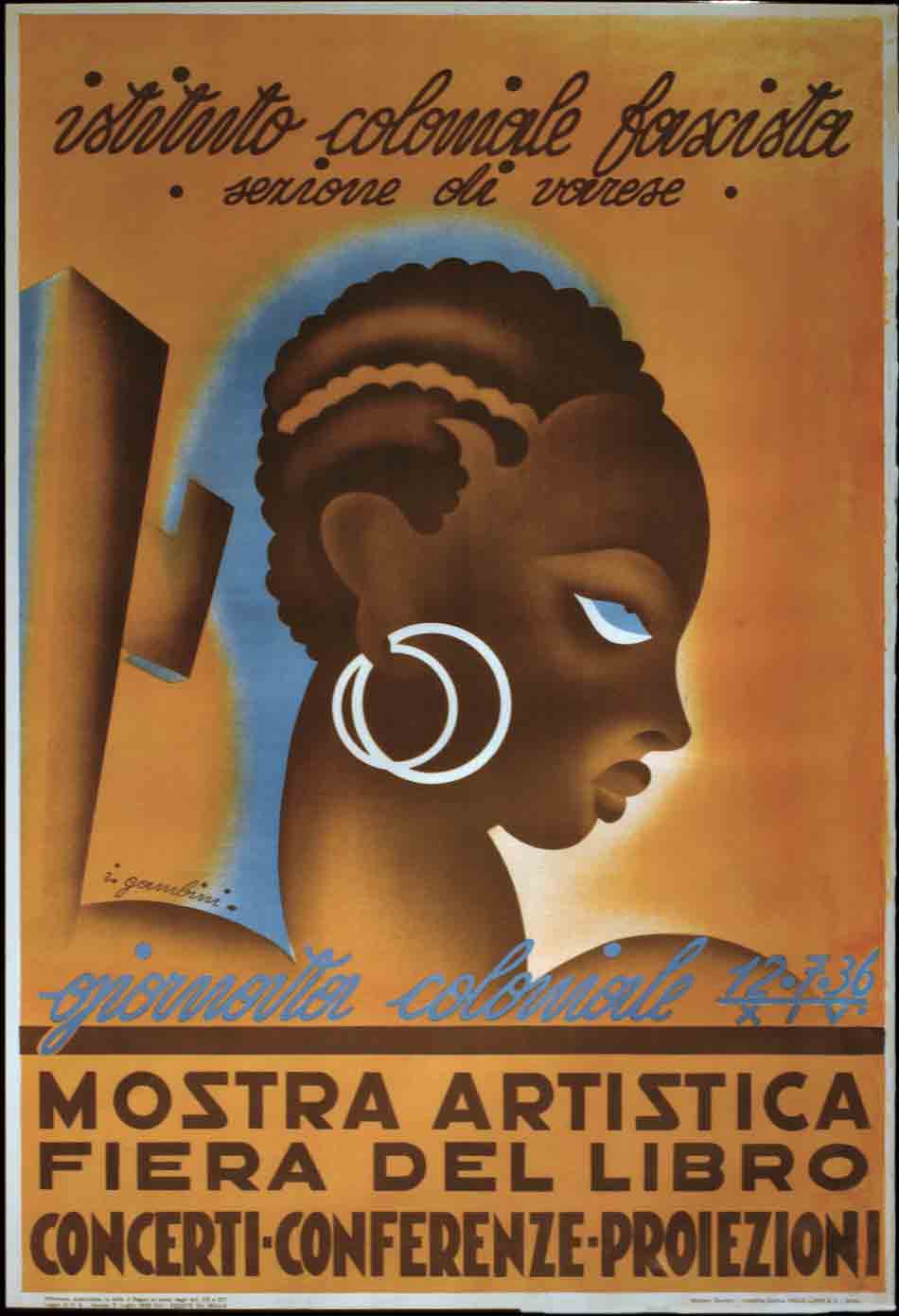

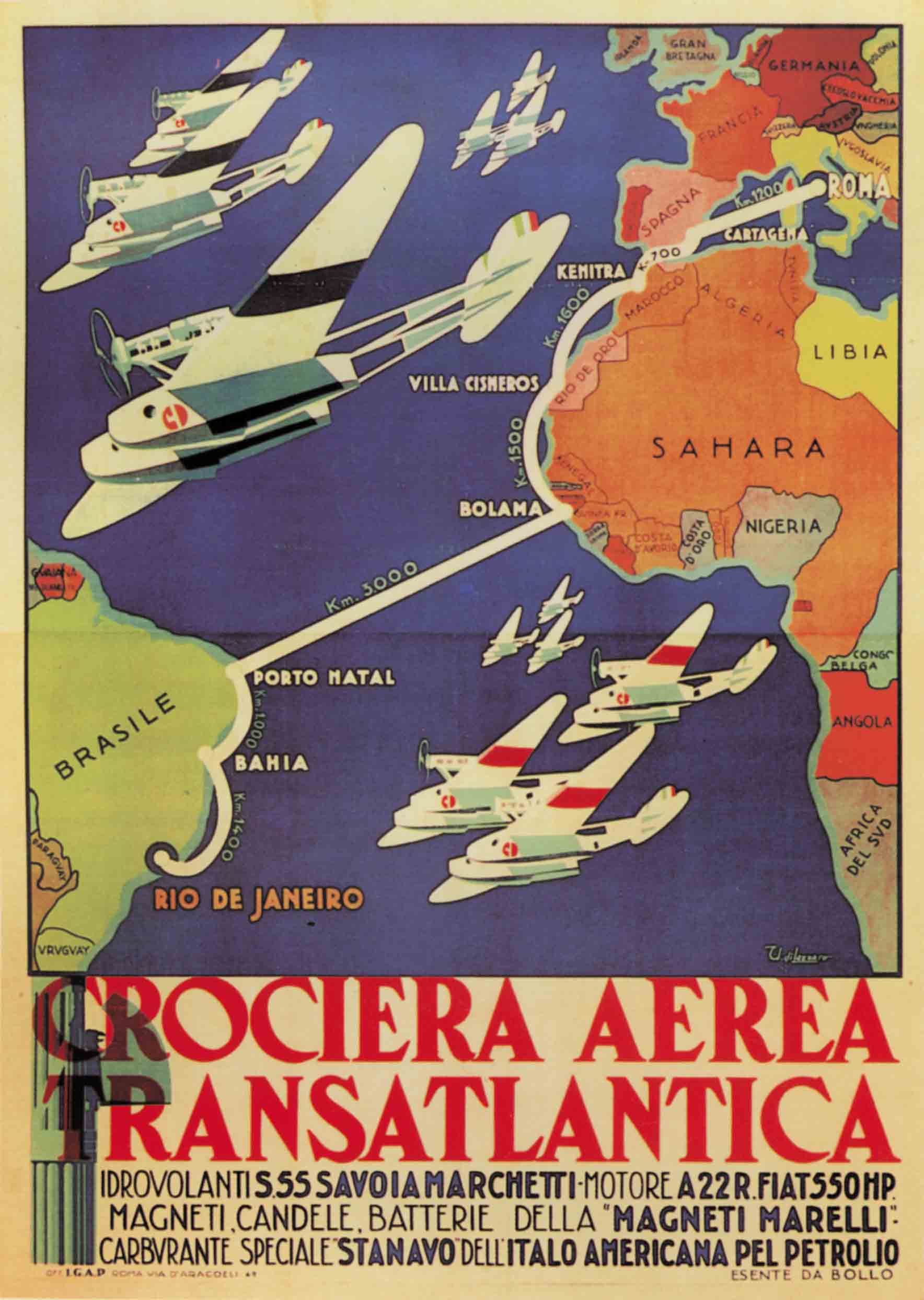

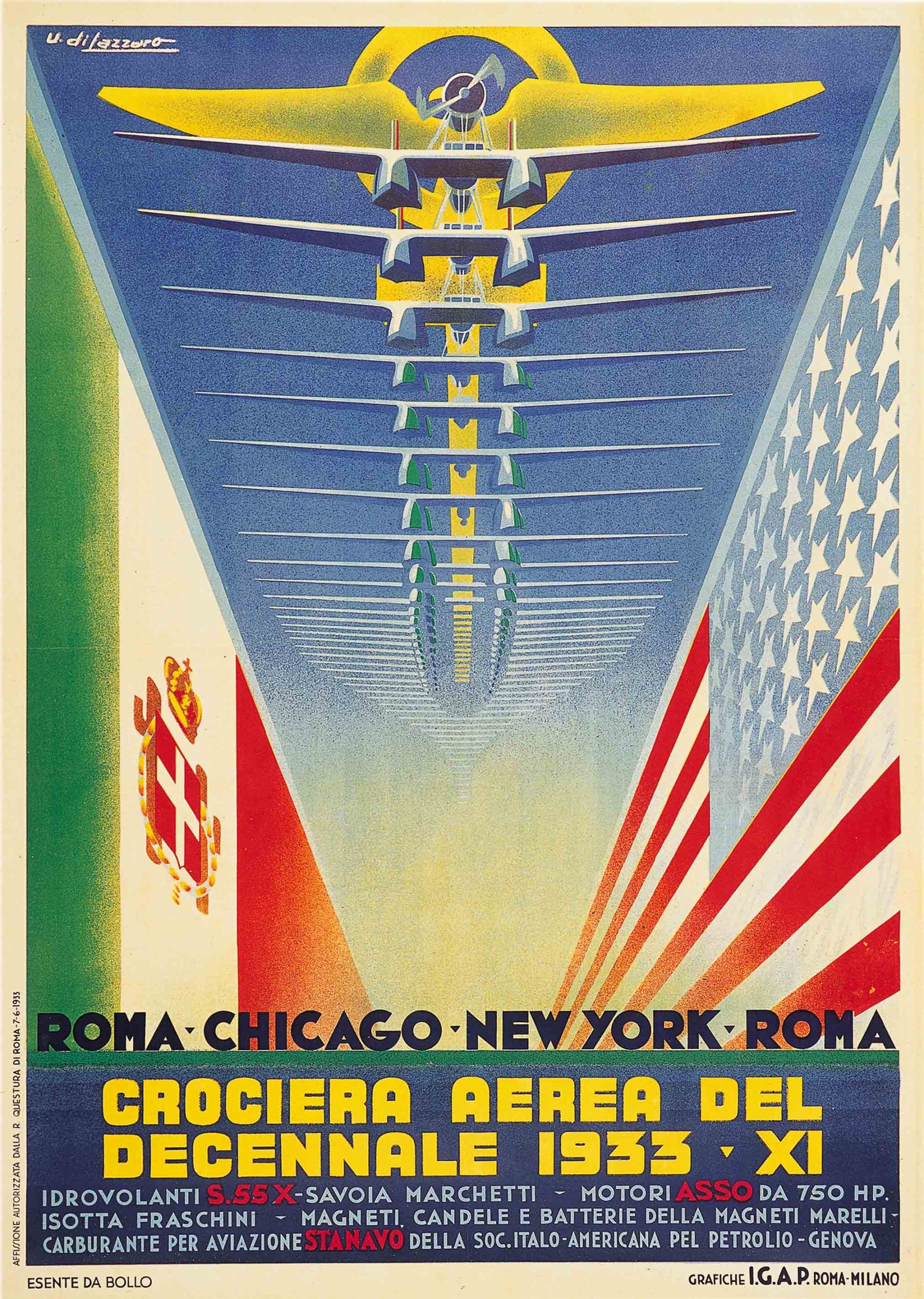

Two years later, after his second election, Mussolini completely replaced the government with extreme loyalists. He stated his goals for the nation he intended to build: its reemergence as a world power and the reestablishment of the Roman empire, offering pride to the people and glory to the country. The next 21 years would be among the most turbulent in the history of a peninsula with two millennia of turmoil preceding it: the then-fledgling nation of Italy—only 50 years beyond the reorganization of its scattered duchies, principalities, and provinces into a unified state—underwent a tempestuous shift as it was electrified by colonialist, industrialist, and racist ambitions that would take it into World War II, its own civil war, and, finally, the founding of the modern Italian Republic.

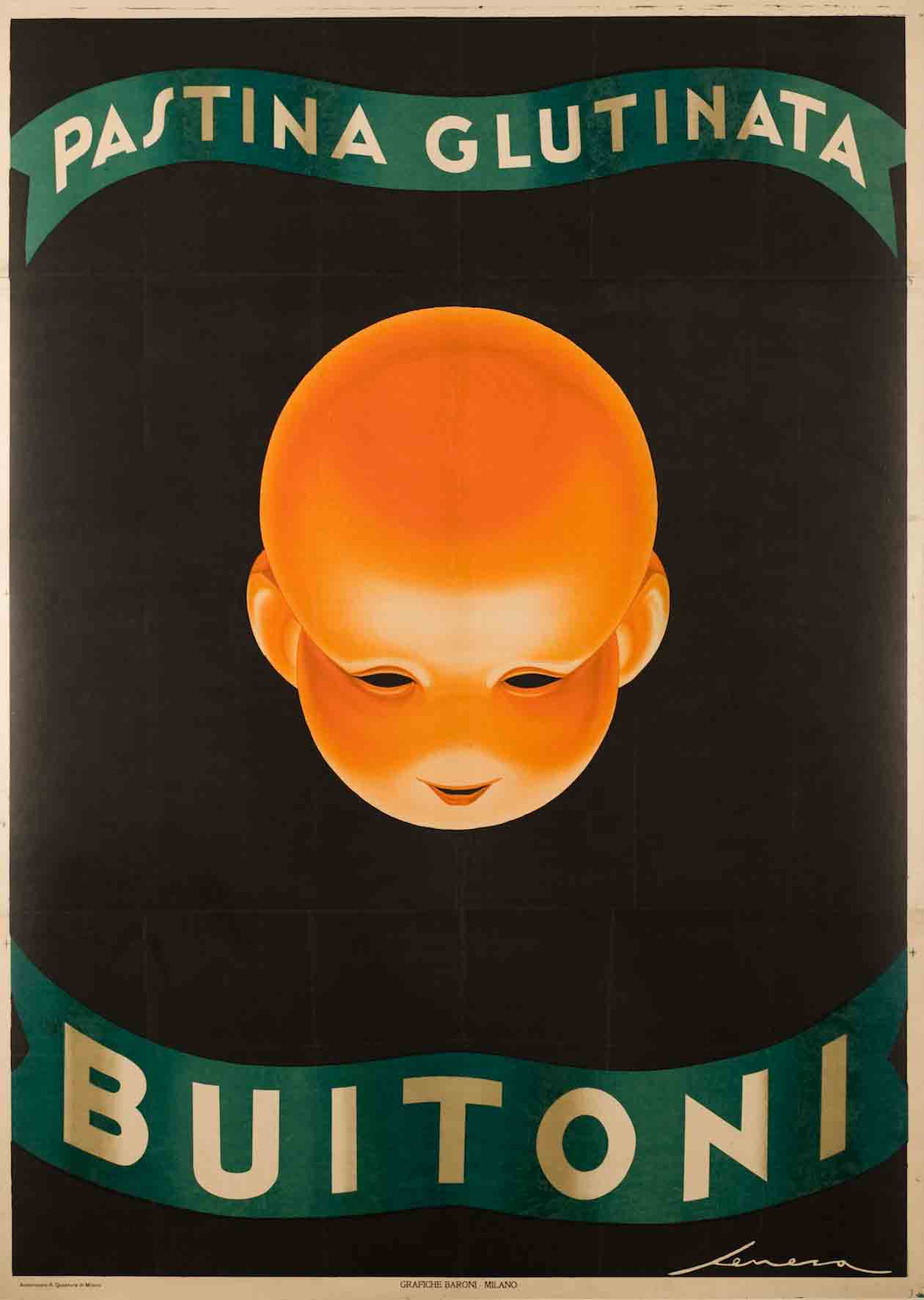

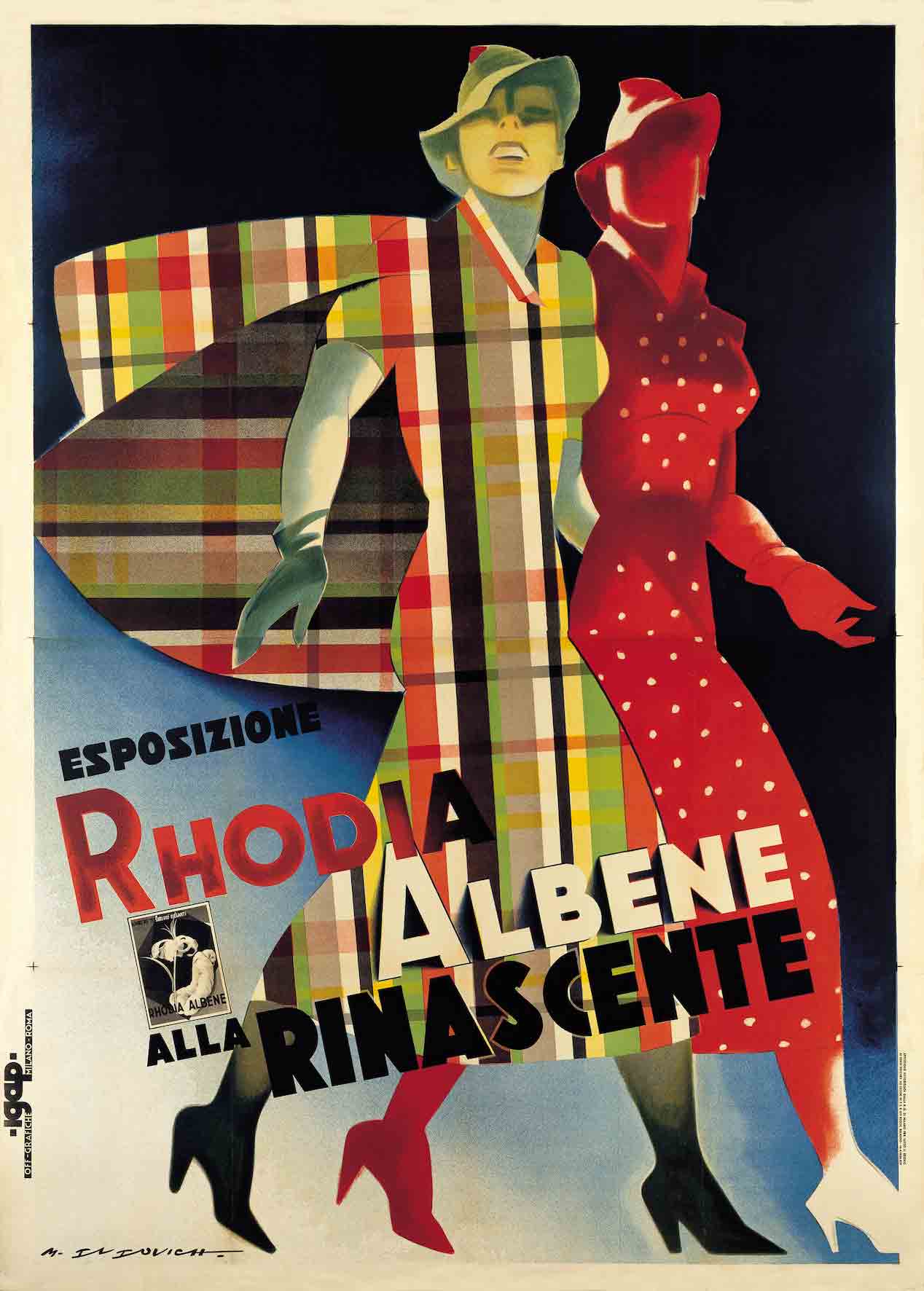

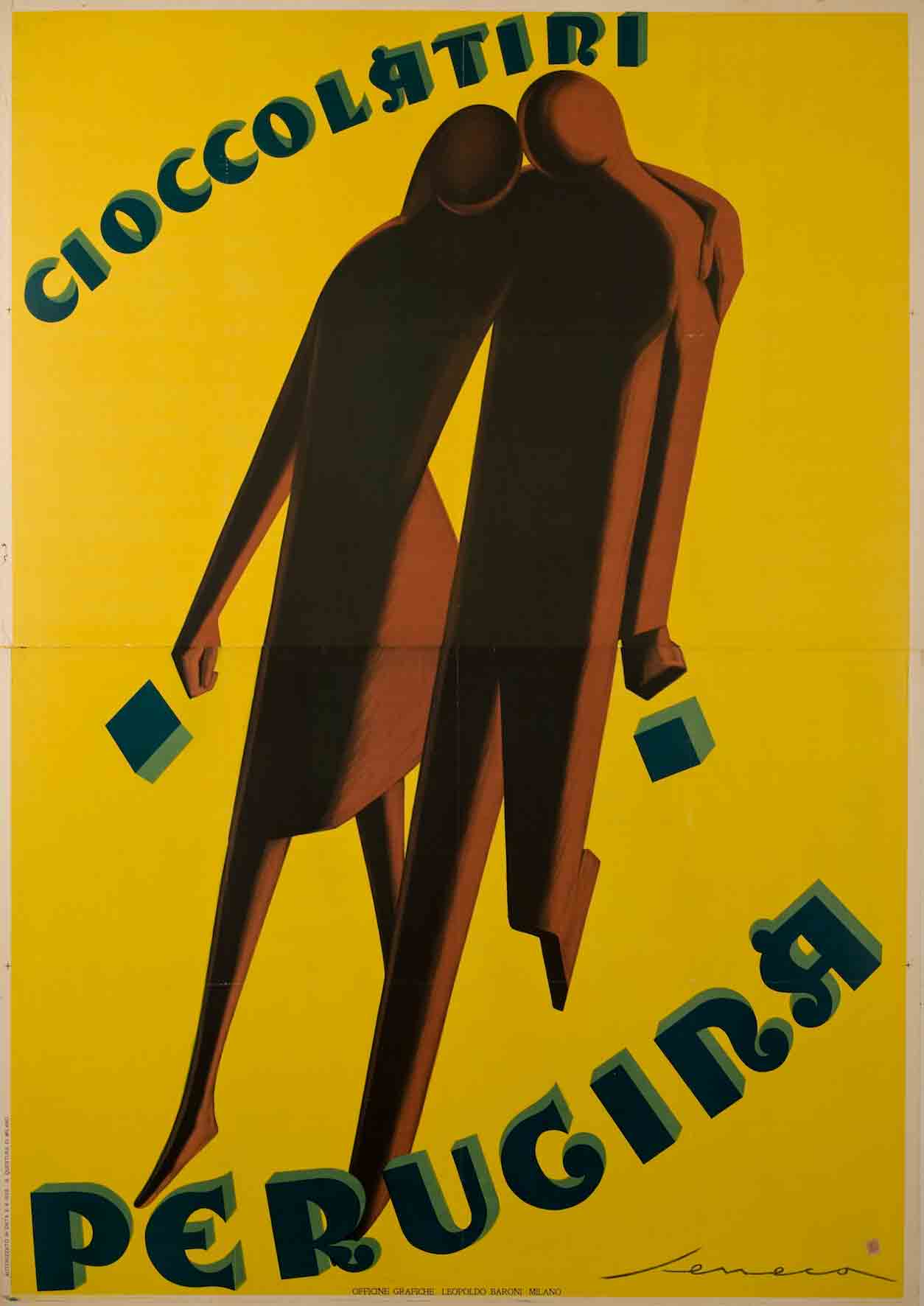

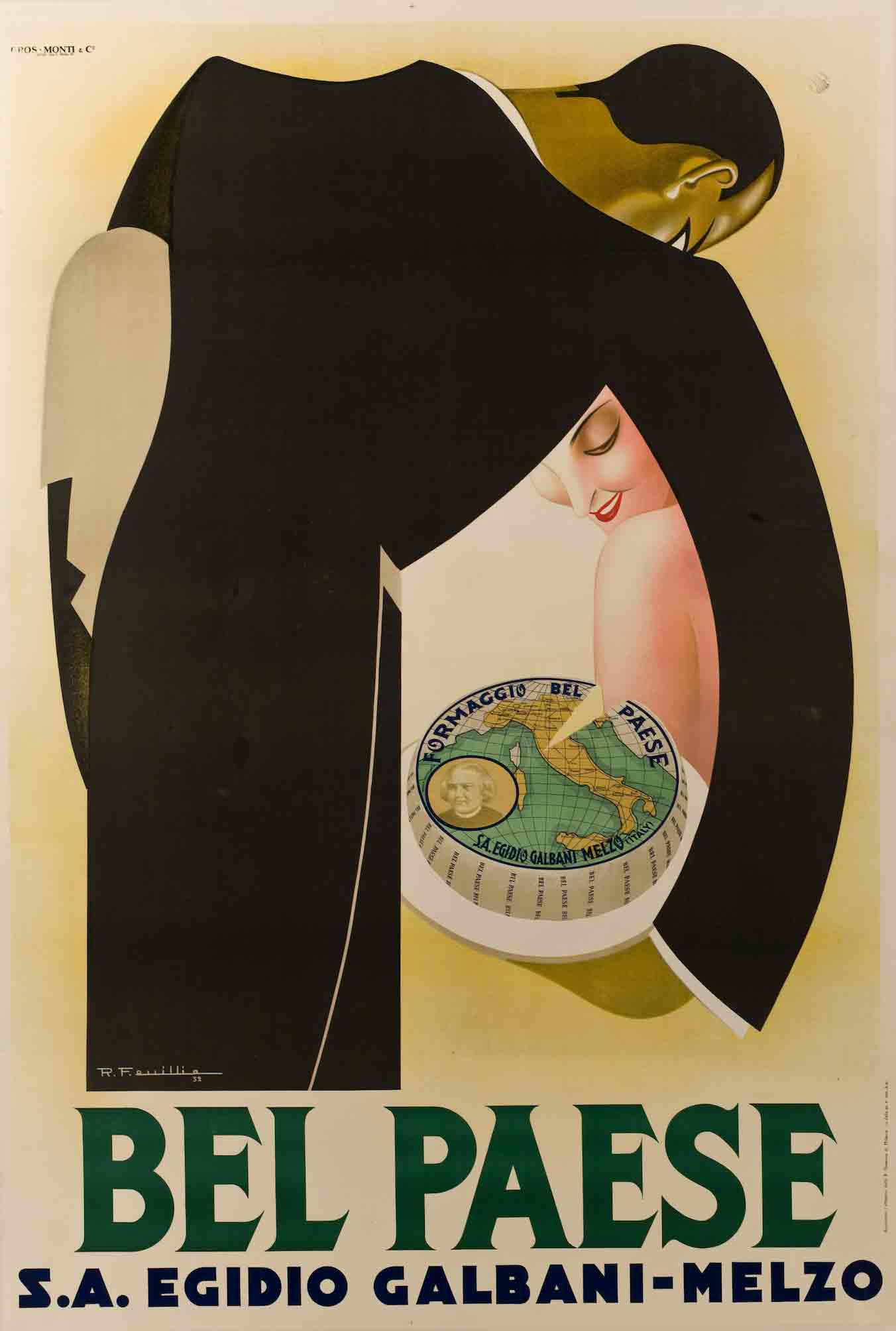

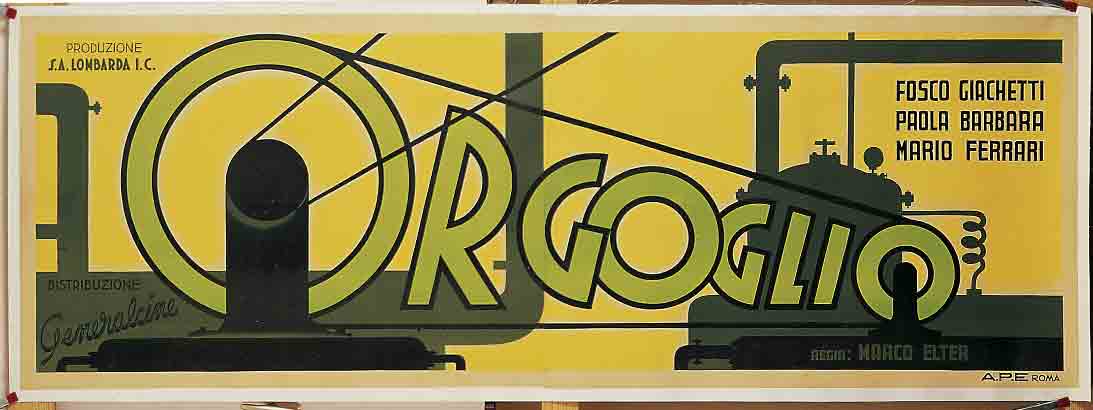

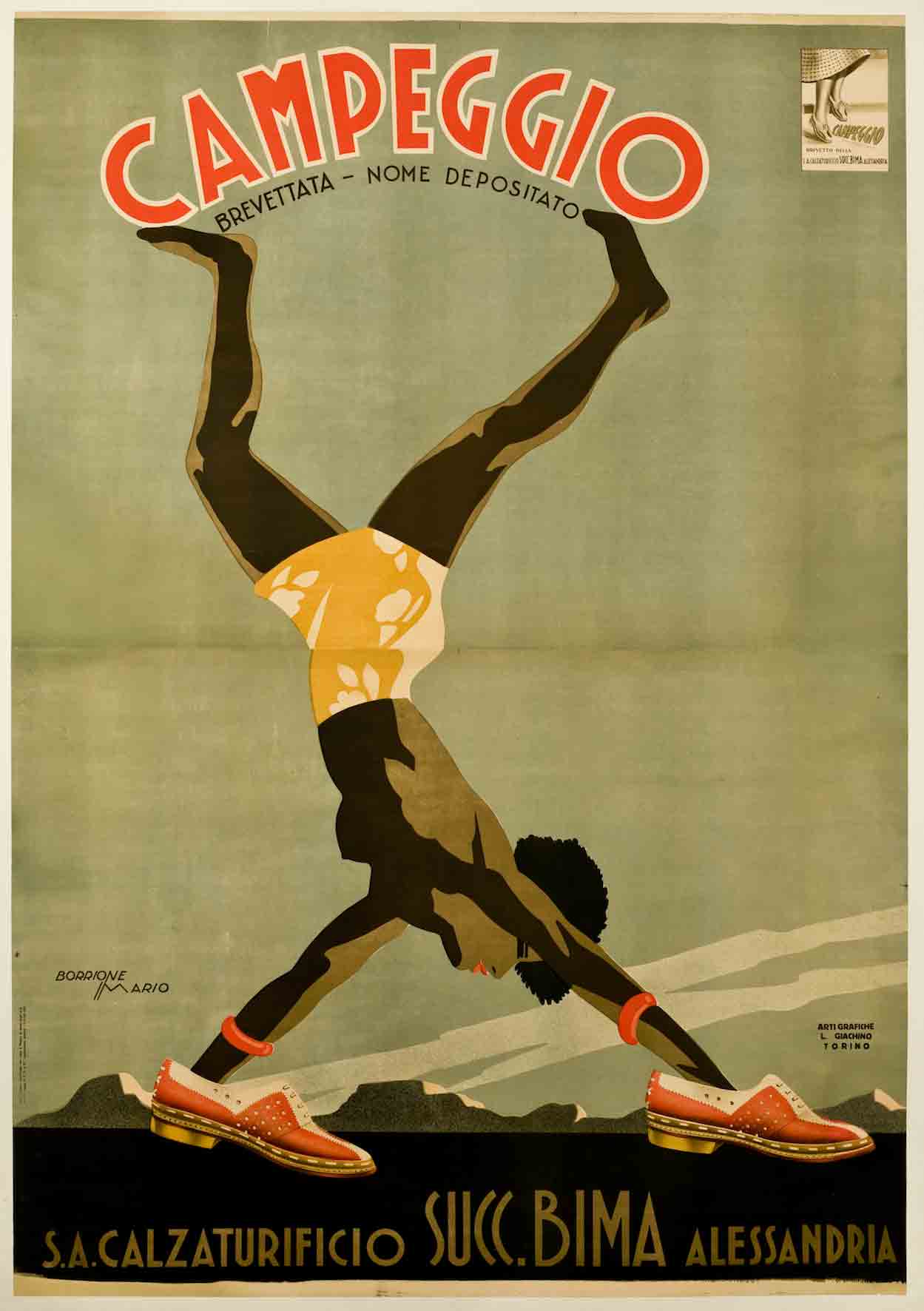

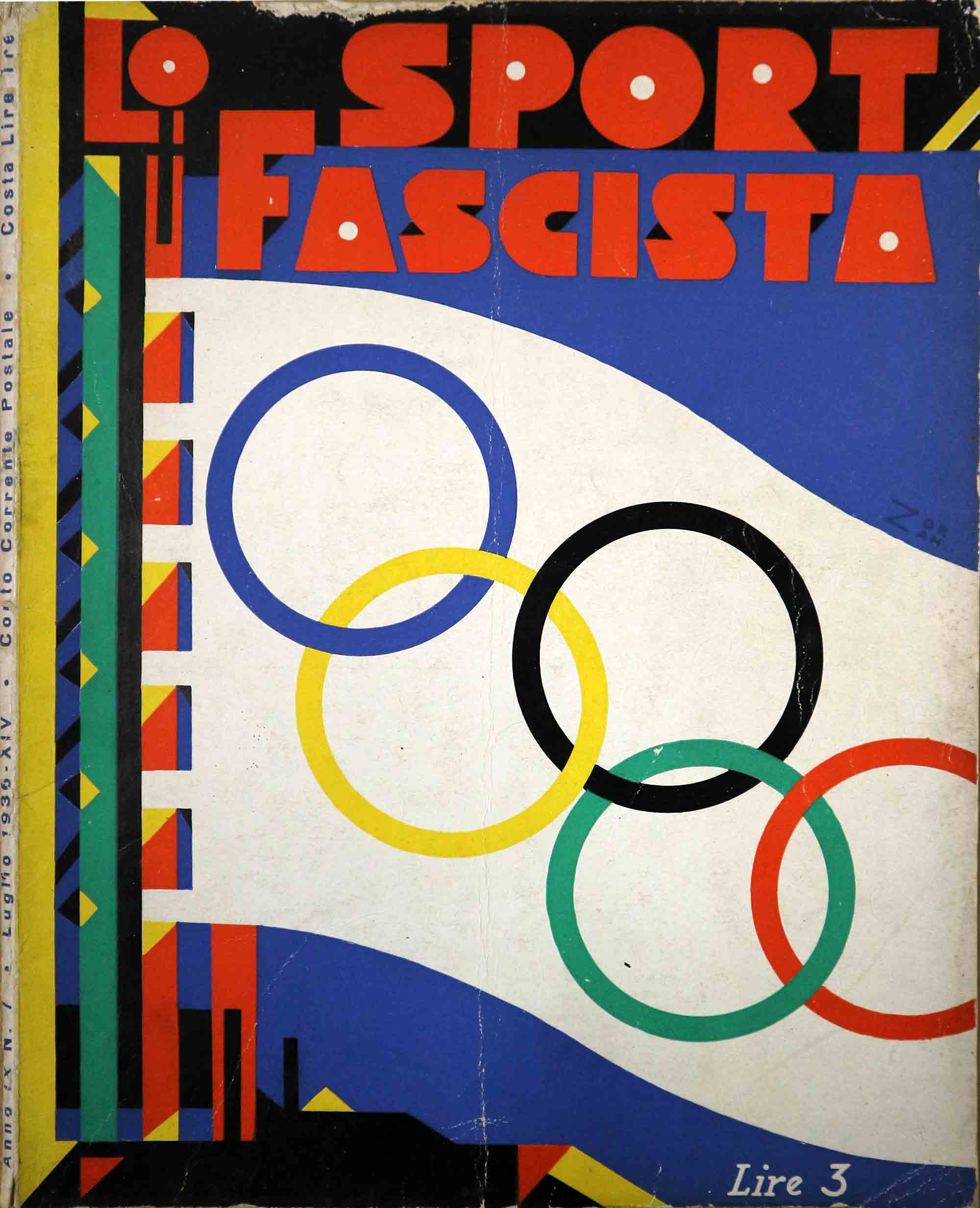

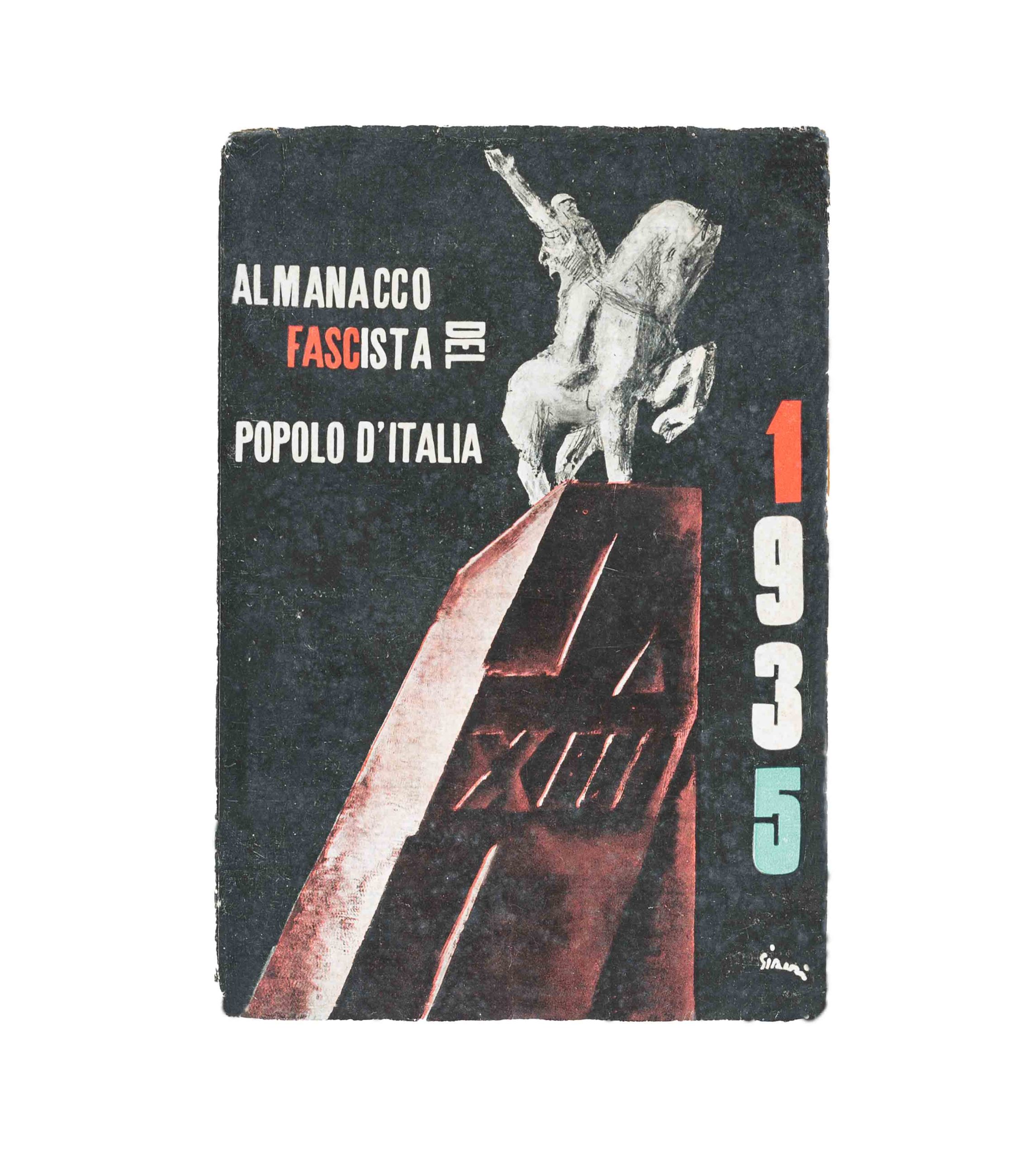

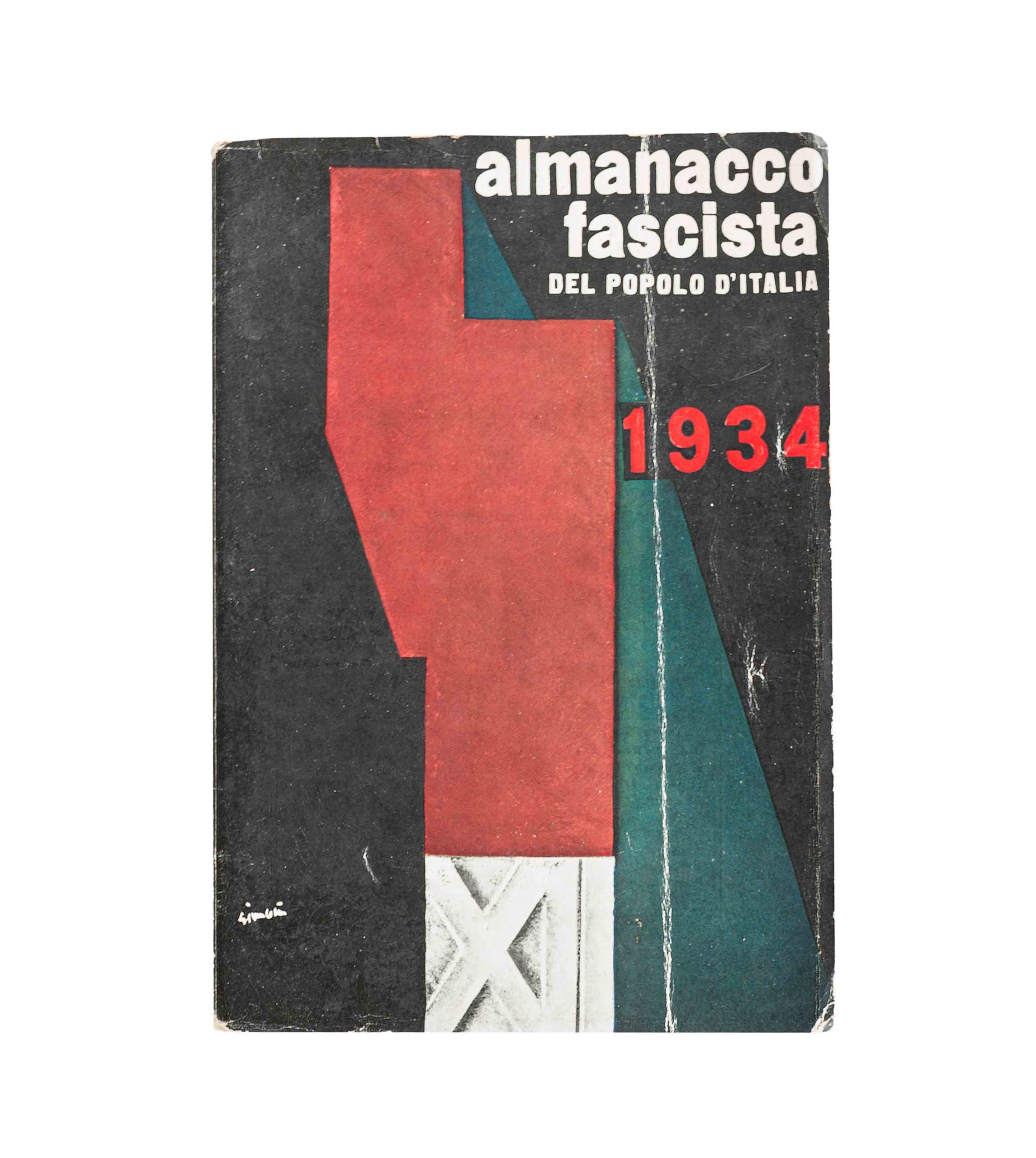

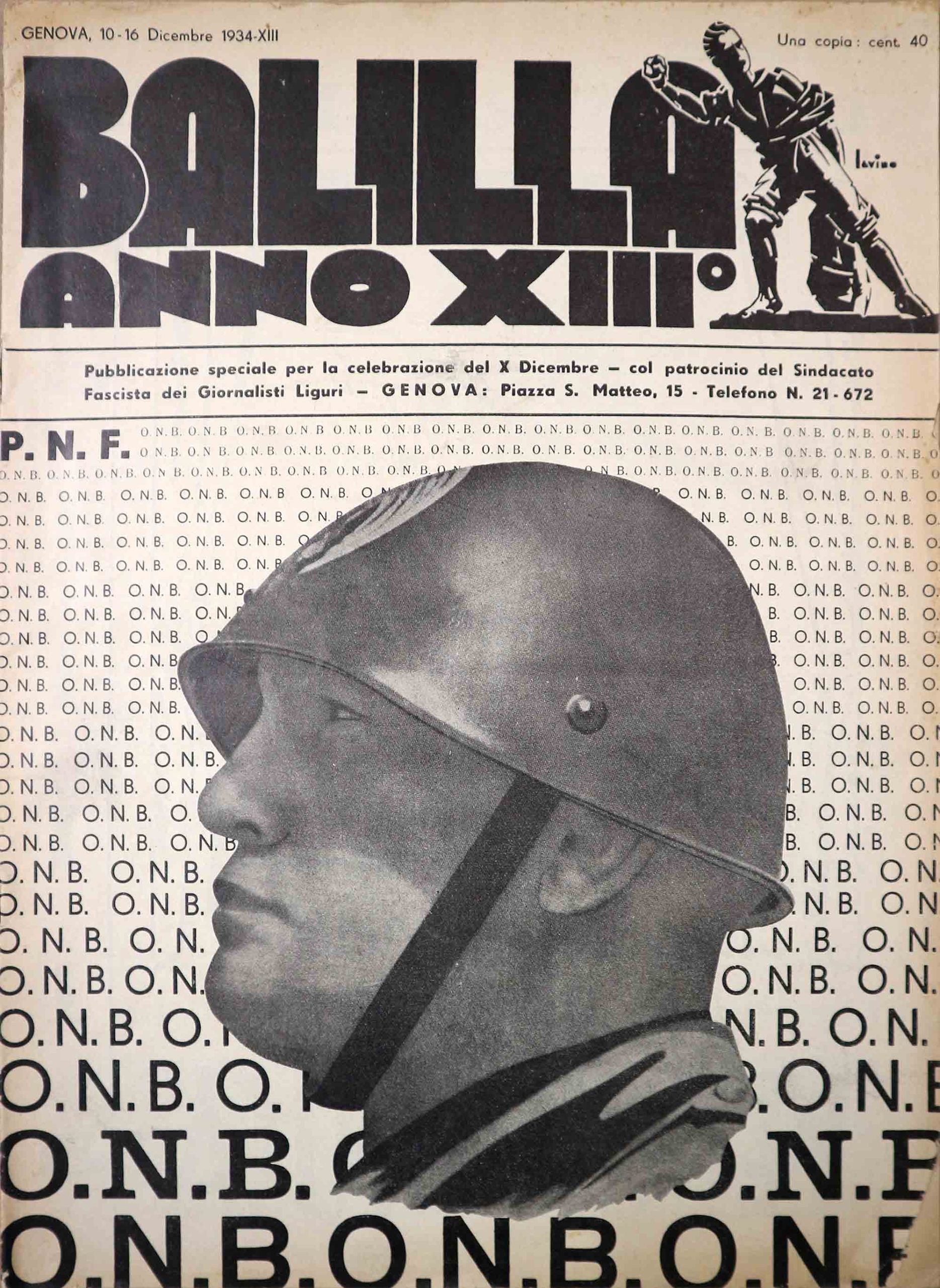

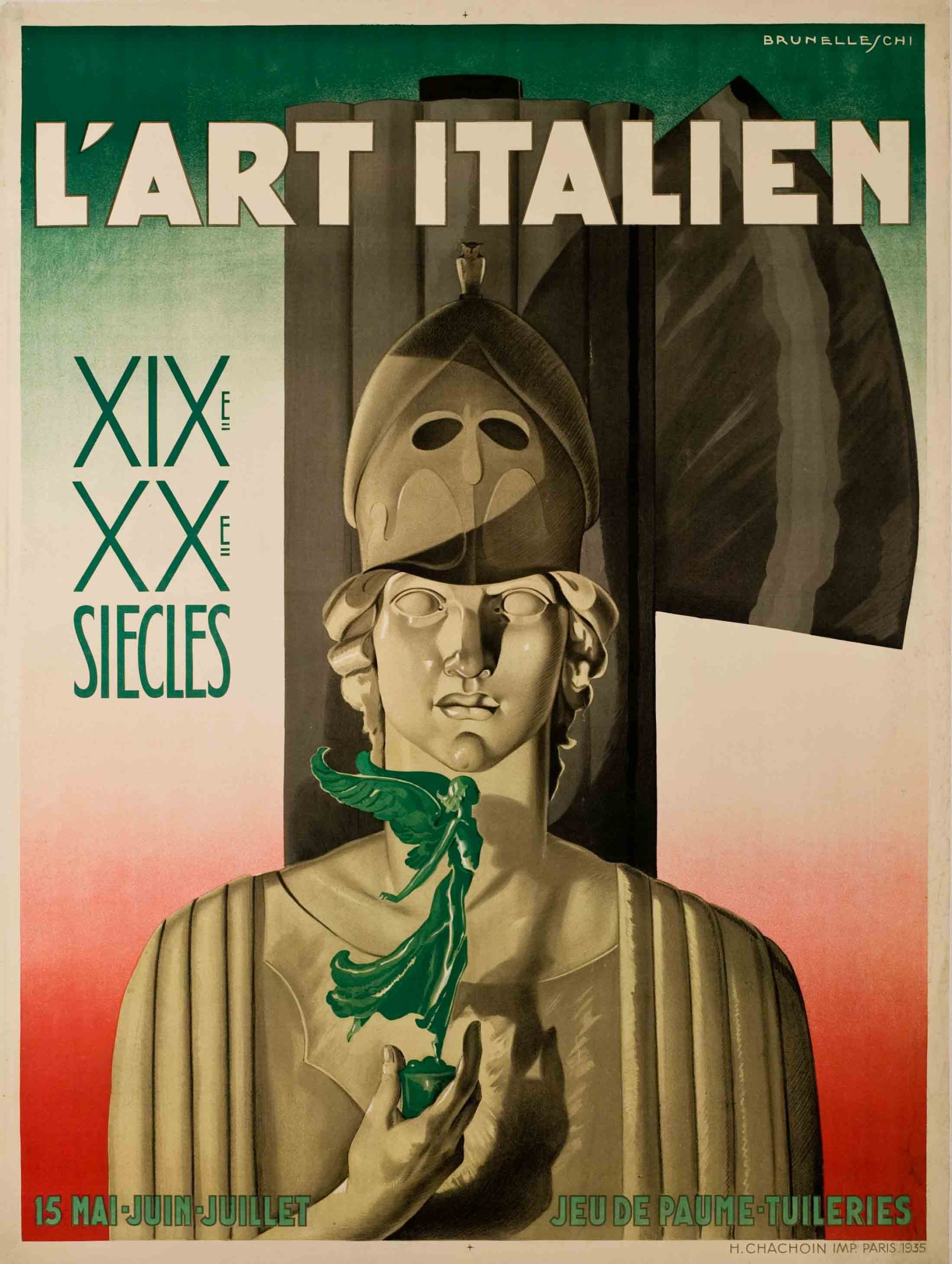

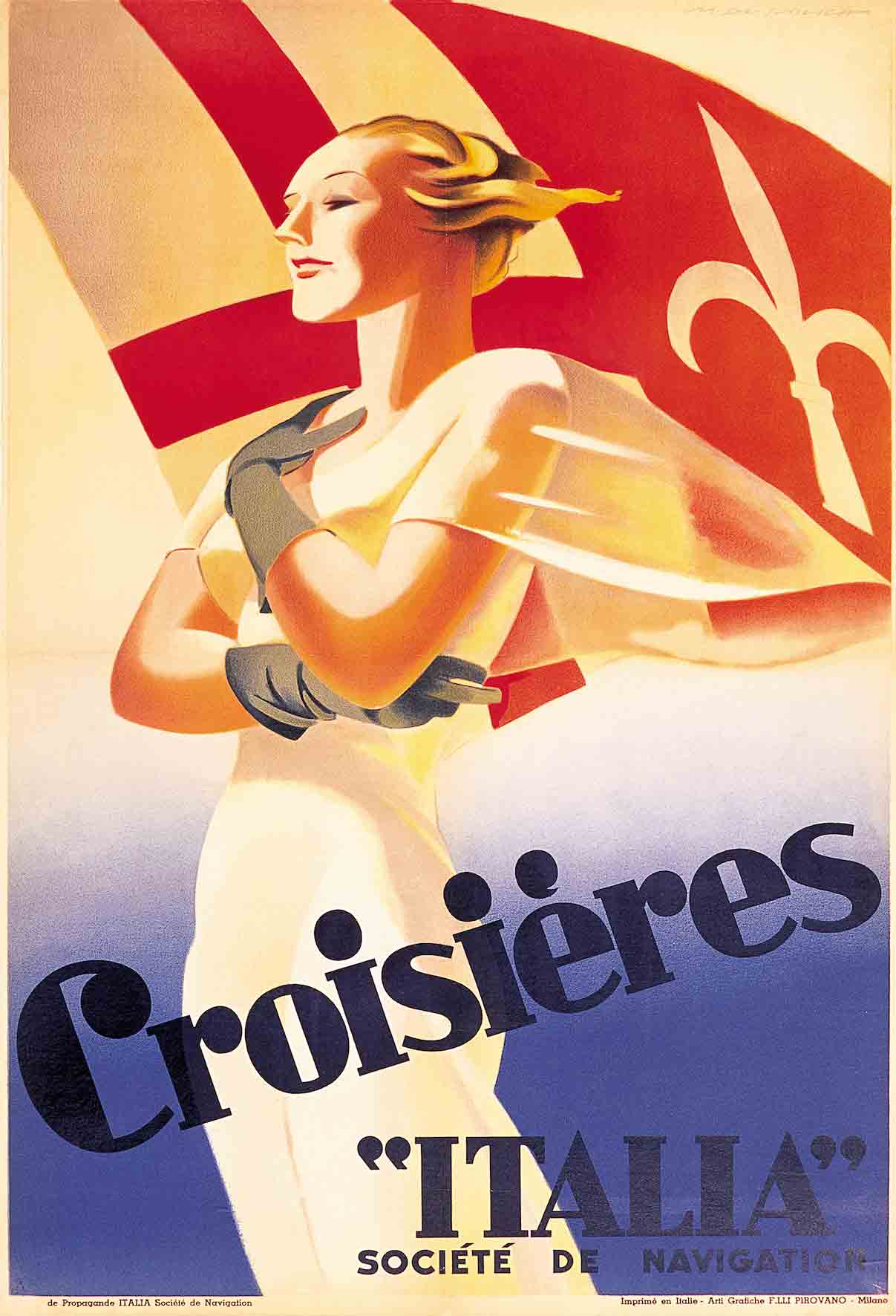

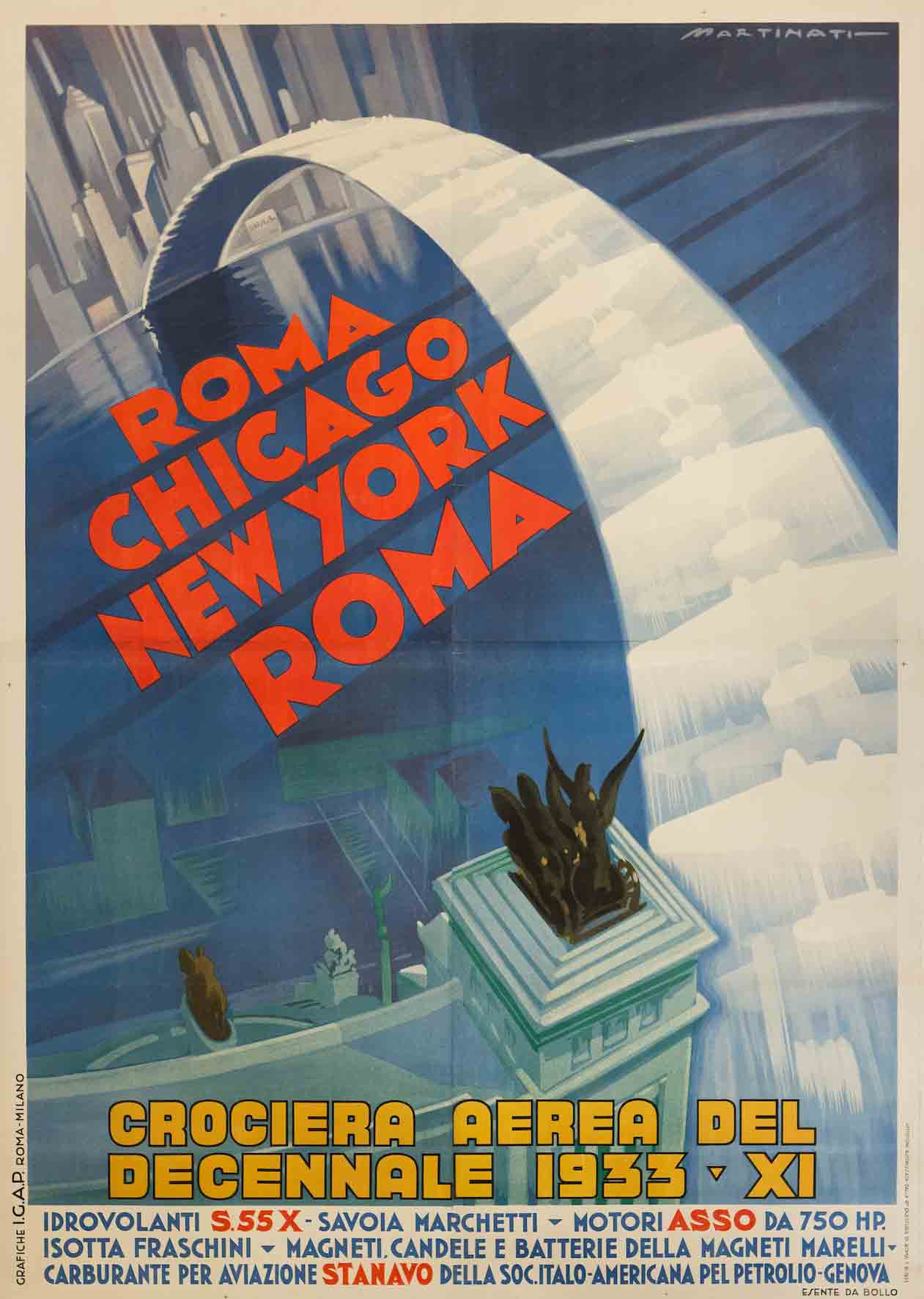

As Italy expanded geographically, culturally, and creatively, it felt for many Italians that the future was now. Through the State—and its tremendous cultural influence on private enterprise—a new national identity was presented, promoted, and urged, in a transformation not only of Italy but of the Italian people.

And so then began the task of selling Italy: at home, abroad, and as an idea in itself.

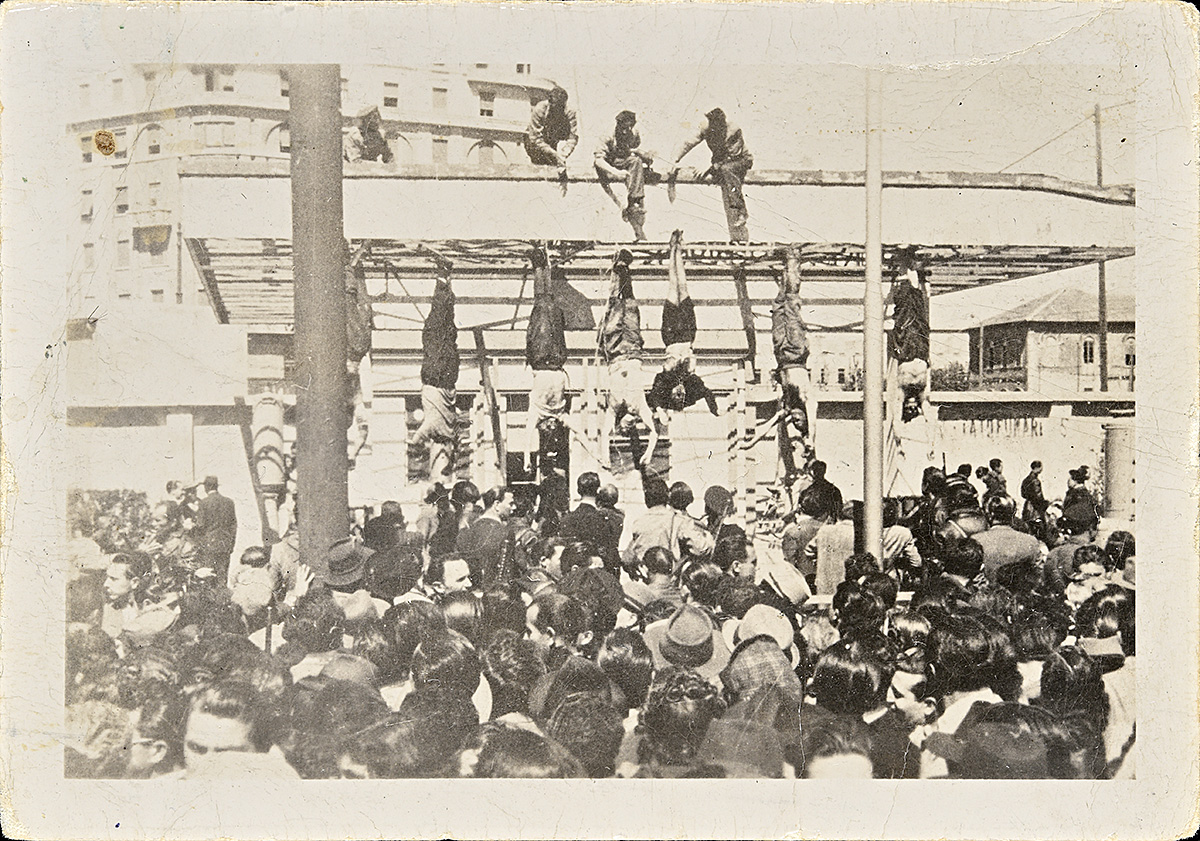

Please note that this exhibition contains violent imagery that some visitors may find disturbing.

Unless otherwise noted, all posters, sculptures, and ephemera are from the Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli Collection, Bologna.

Whenever feasible, Poster House reuses materials from previous shows to drive sustainable practice.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA).

Large text, Spanish translation, and a Plain Language summary are available via the QR code and at the Info Desk.

El texto con letra grande, la traducción al español y un resumen en lectura fácil están disponibles a través del código QR y en atención al público.