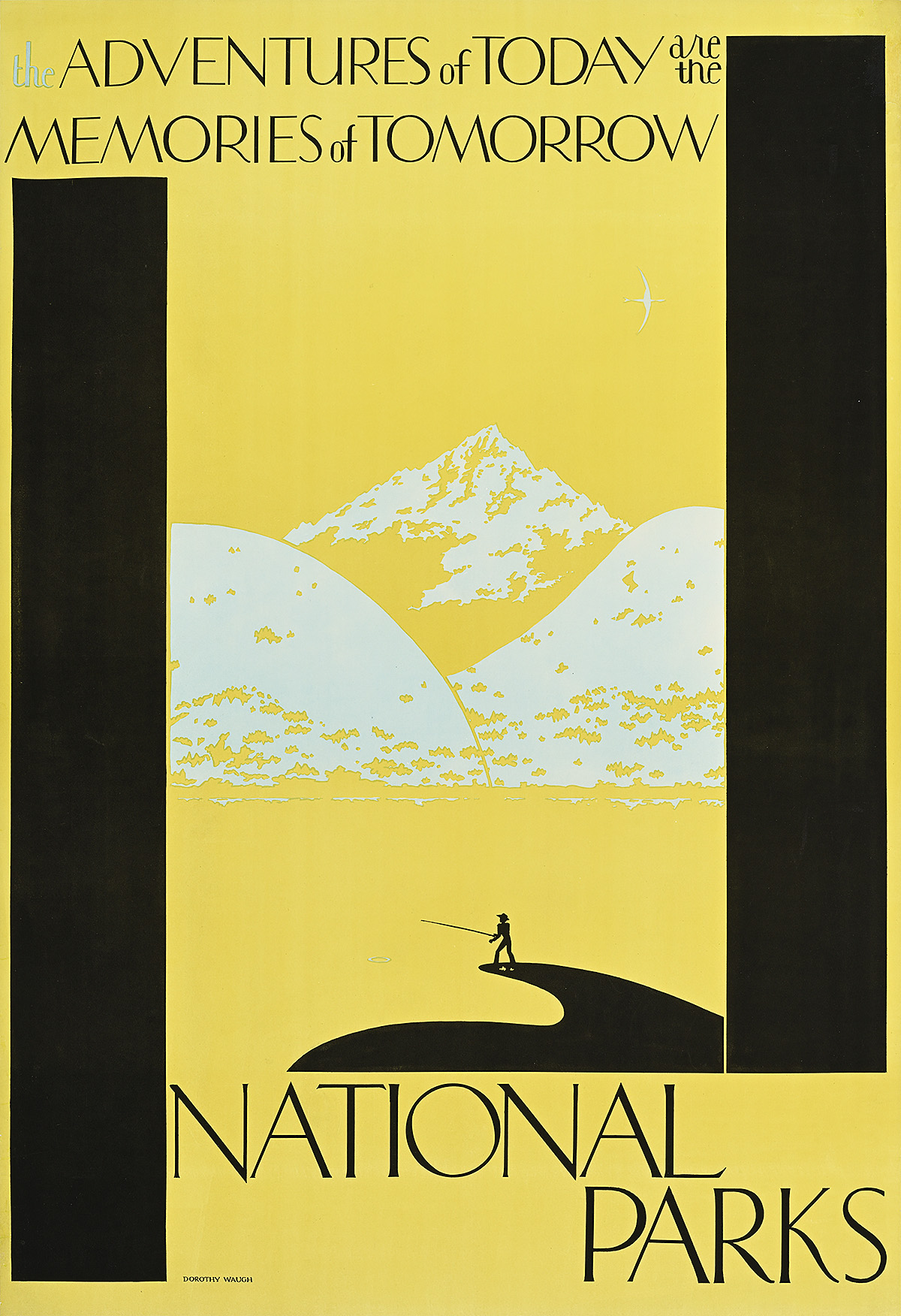

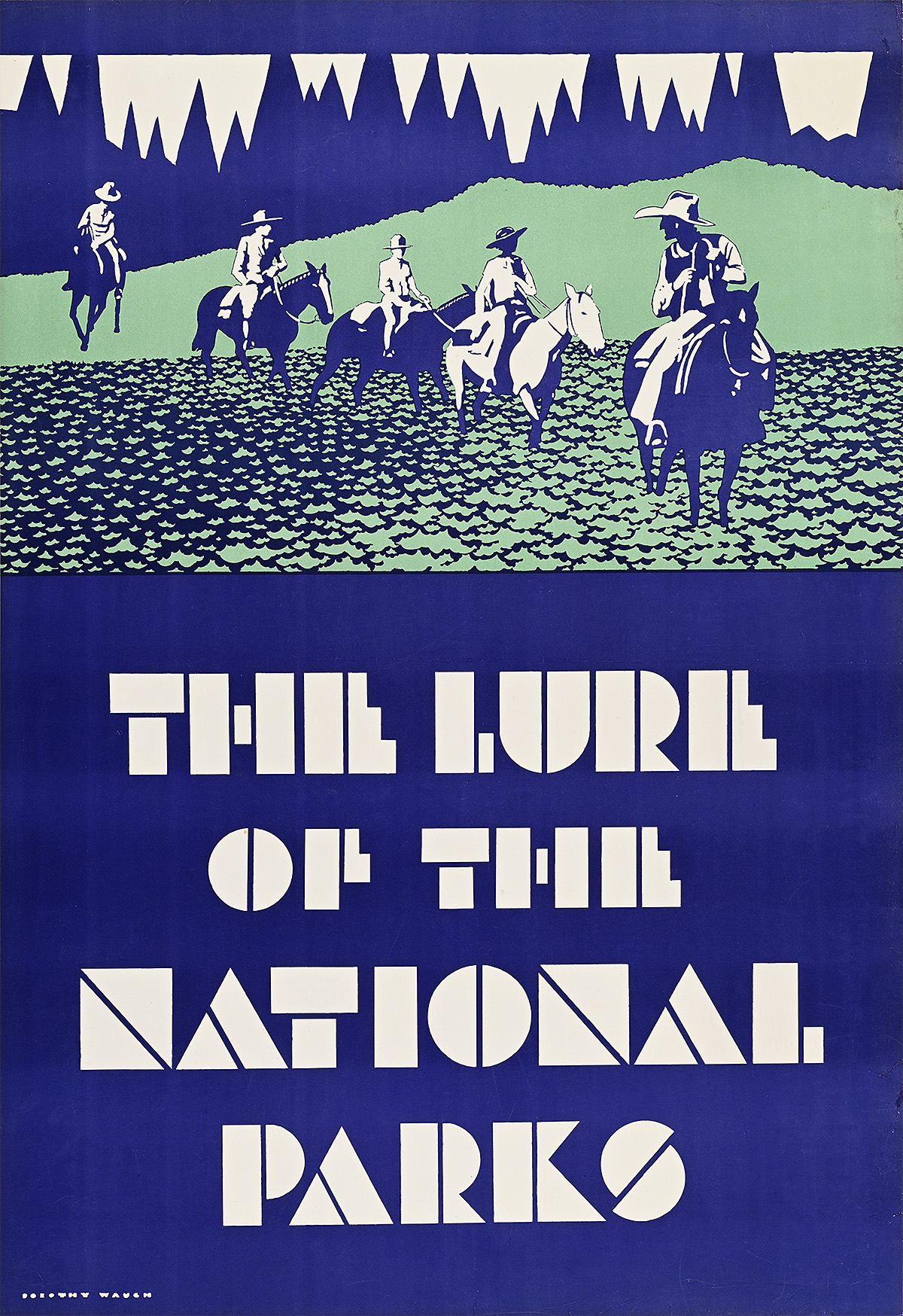

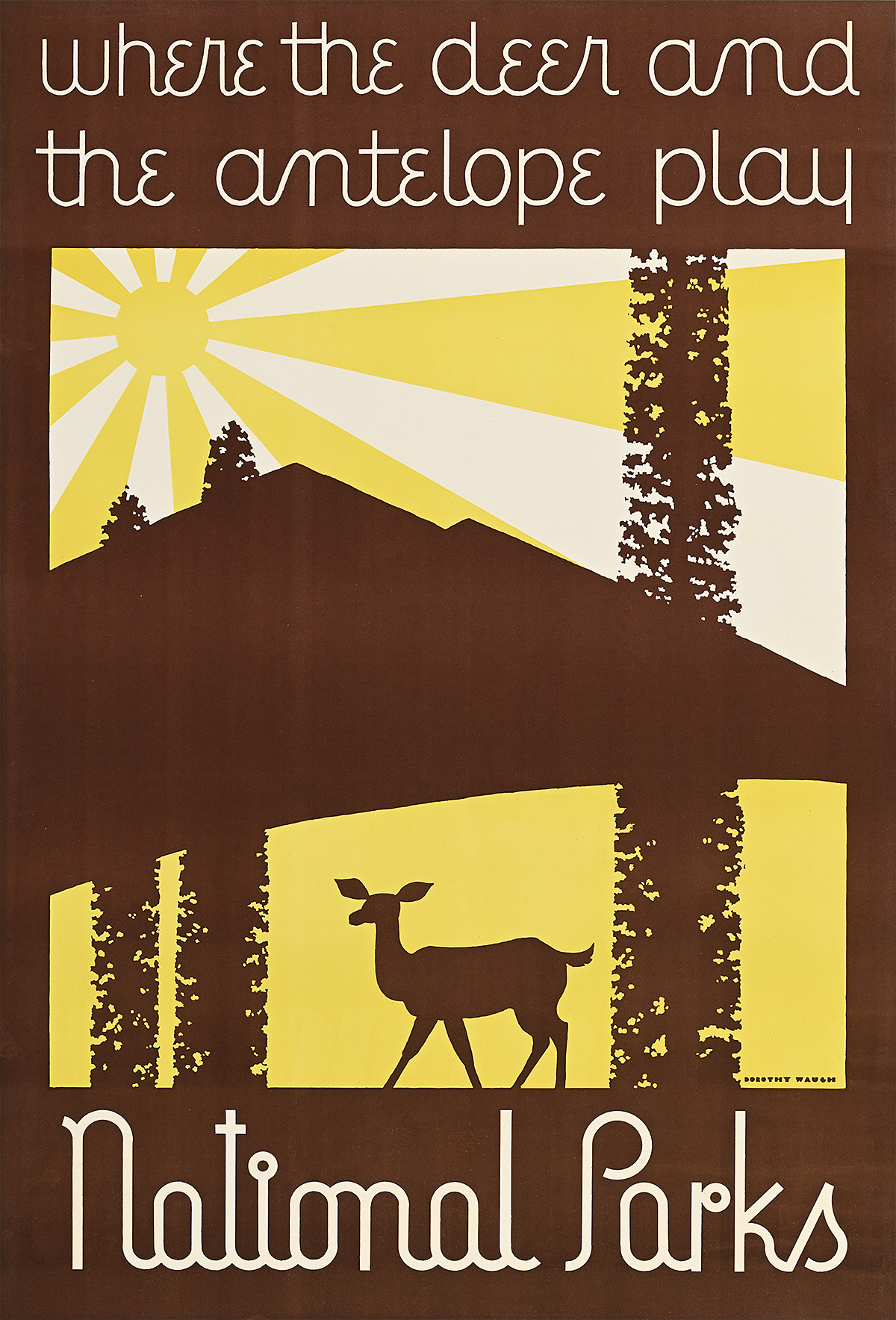

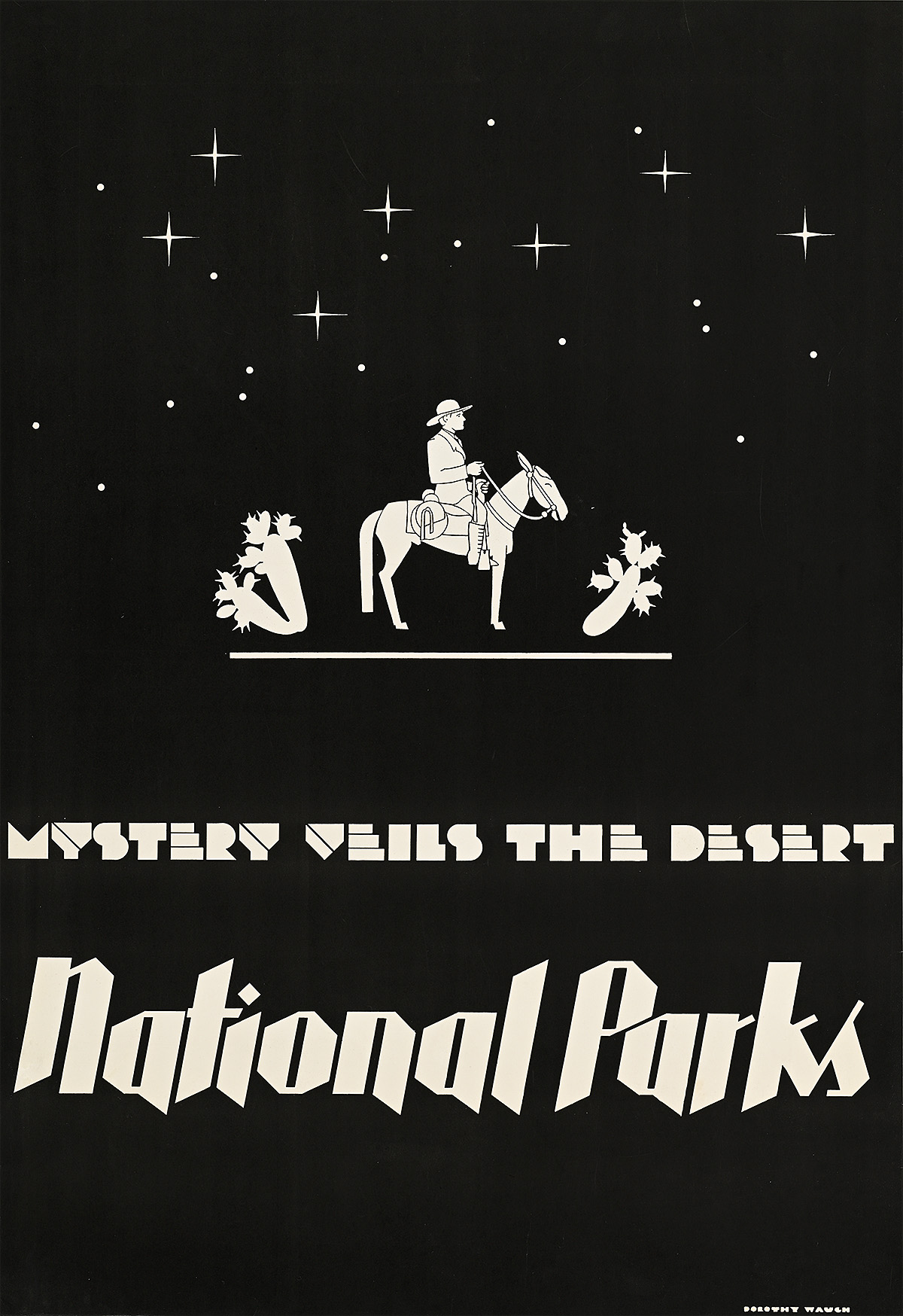

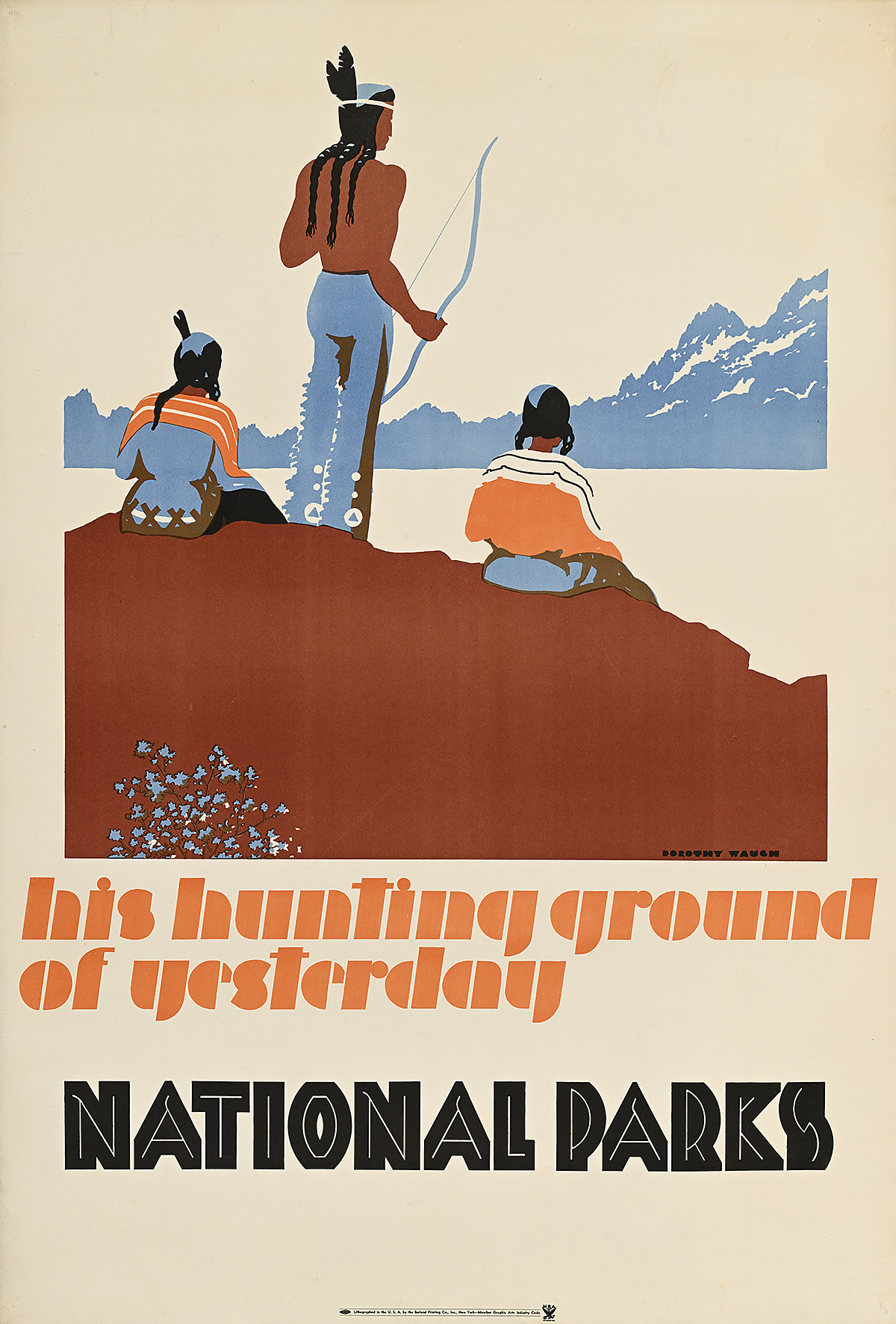

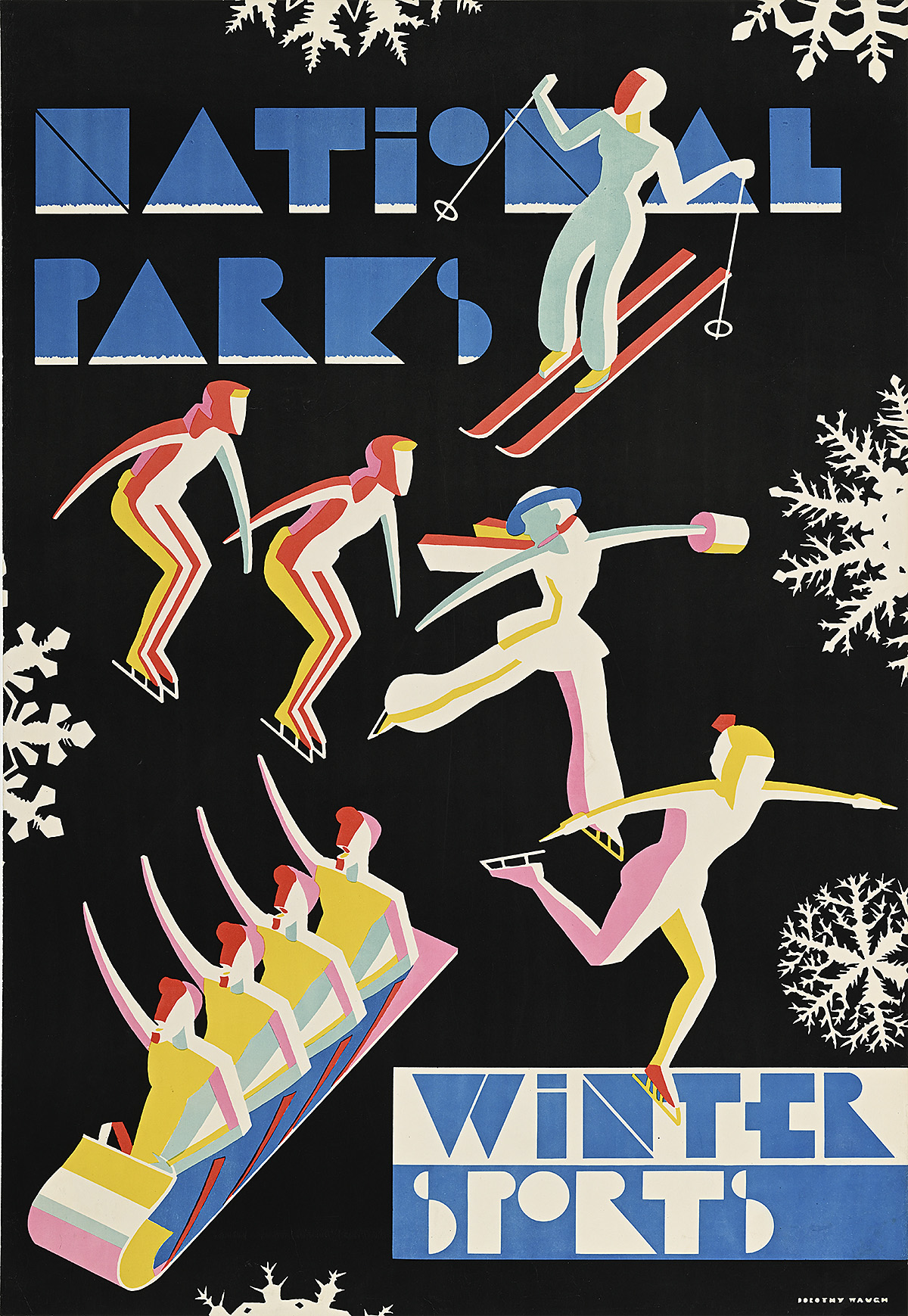

Blazing A Trail: Dorothy Waugh’s National Parks Posters

A Groundbreaking Campaign

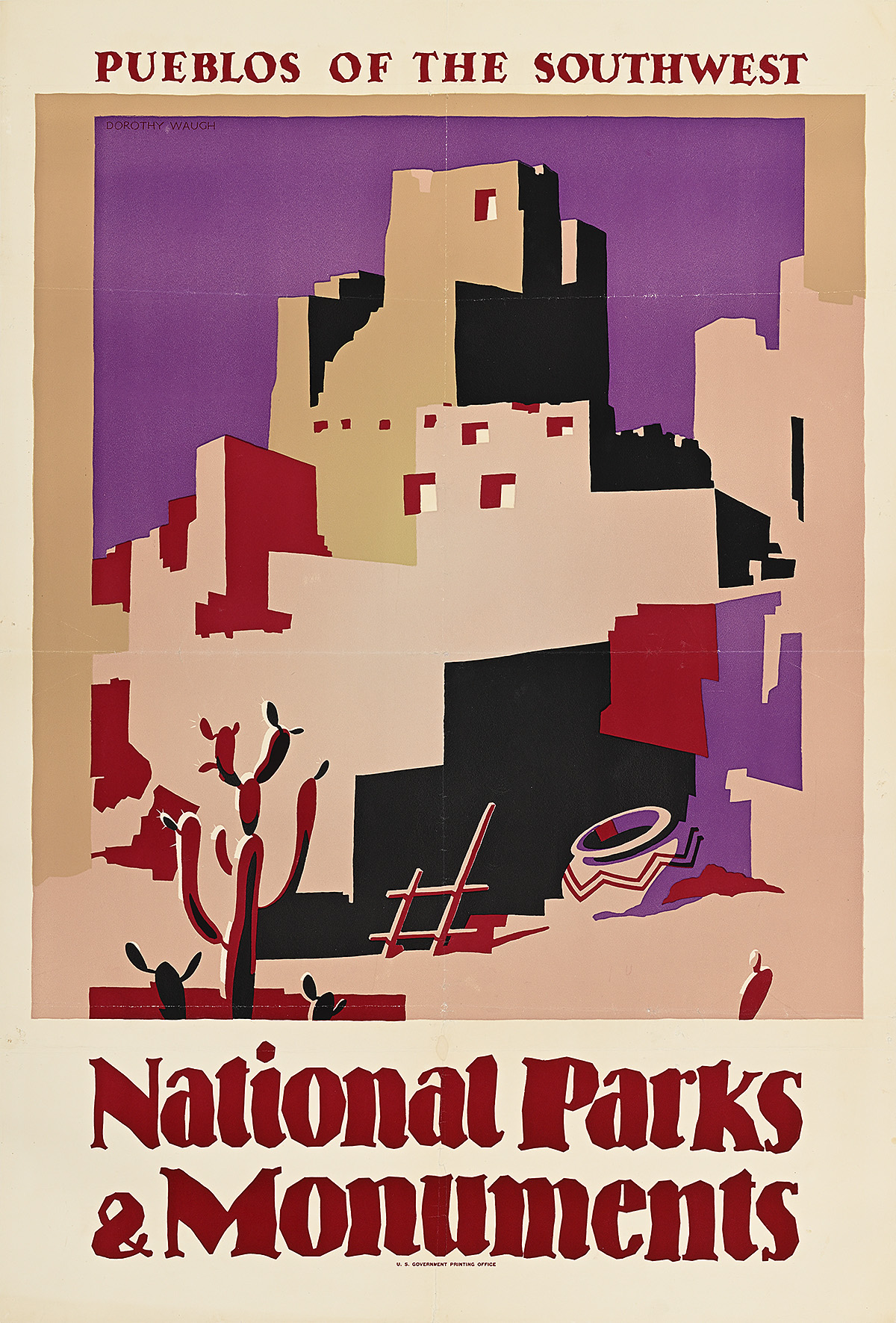

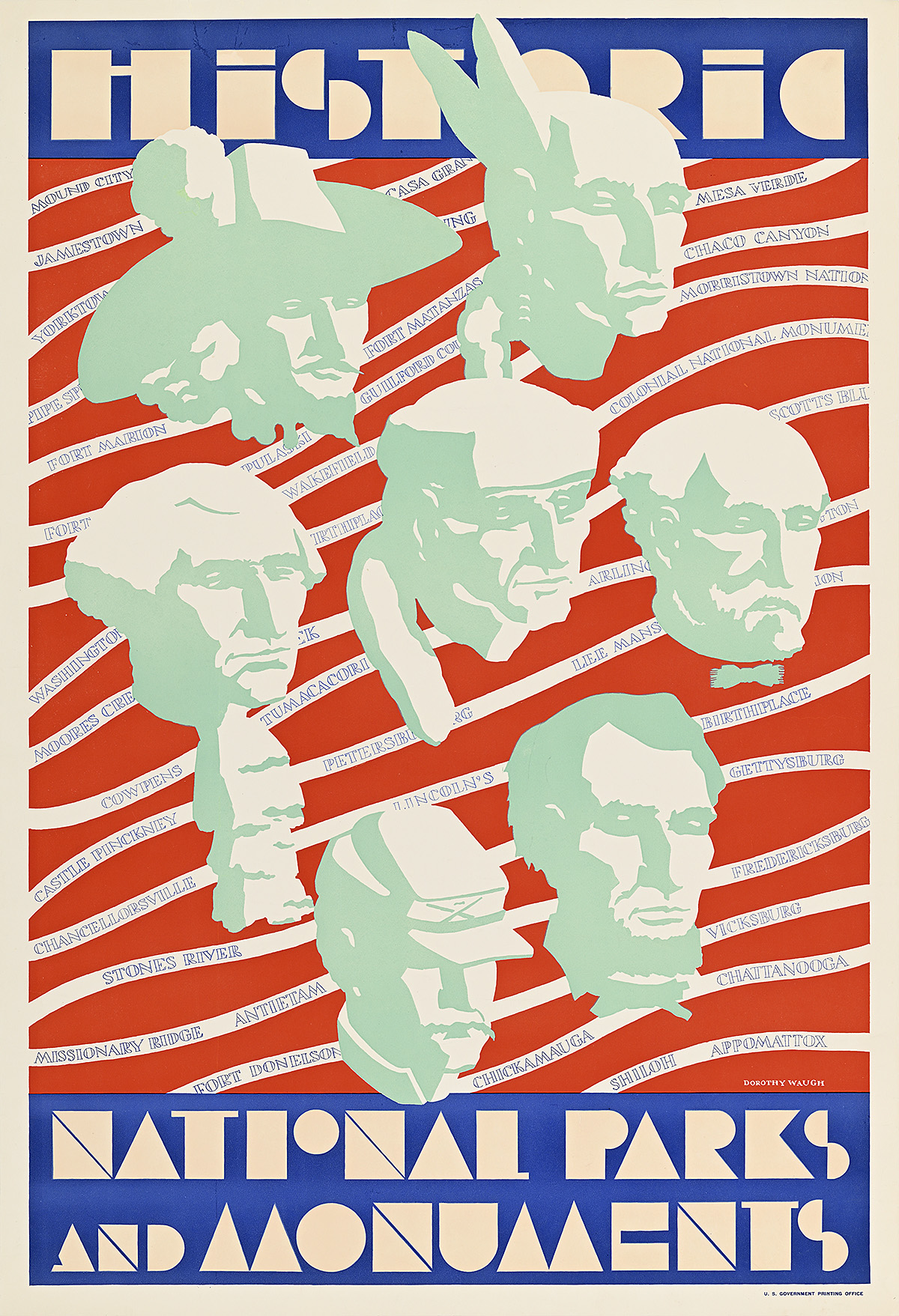

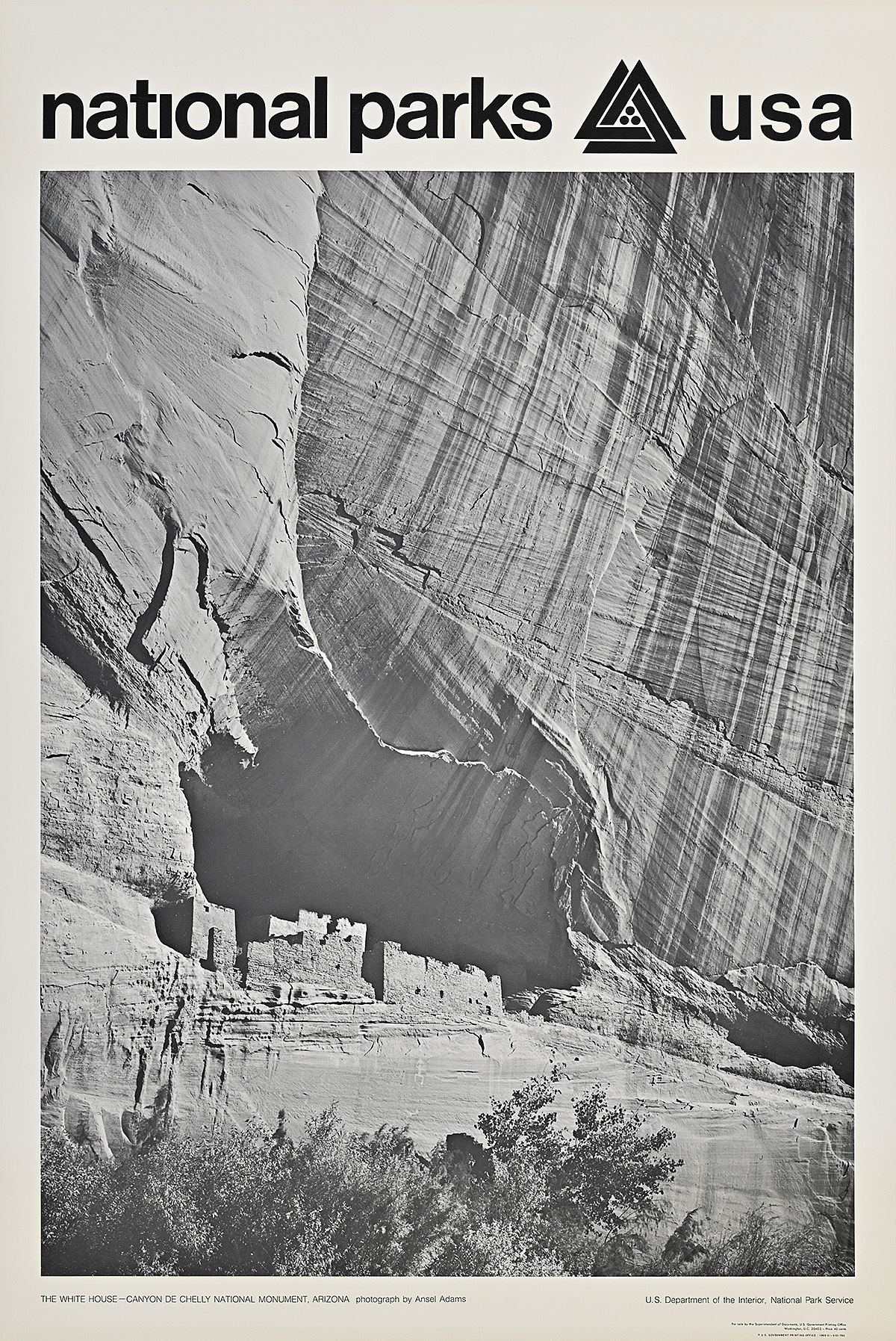

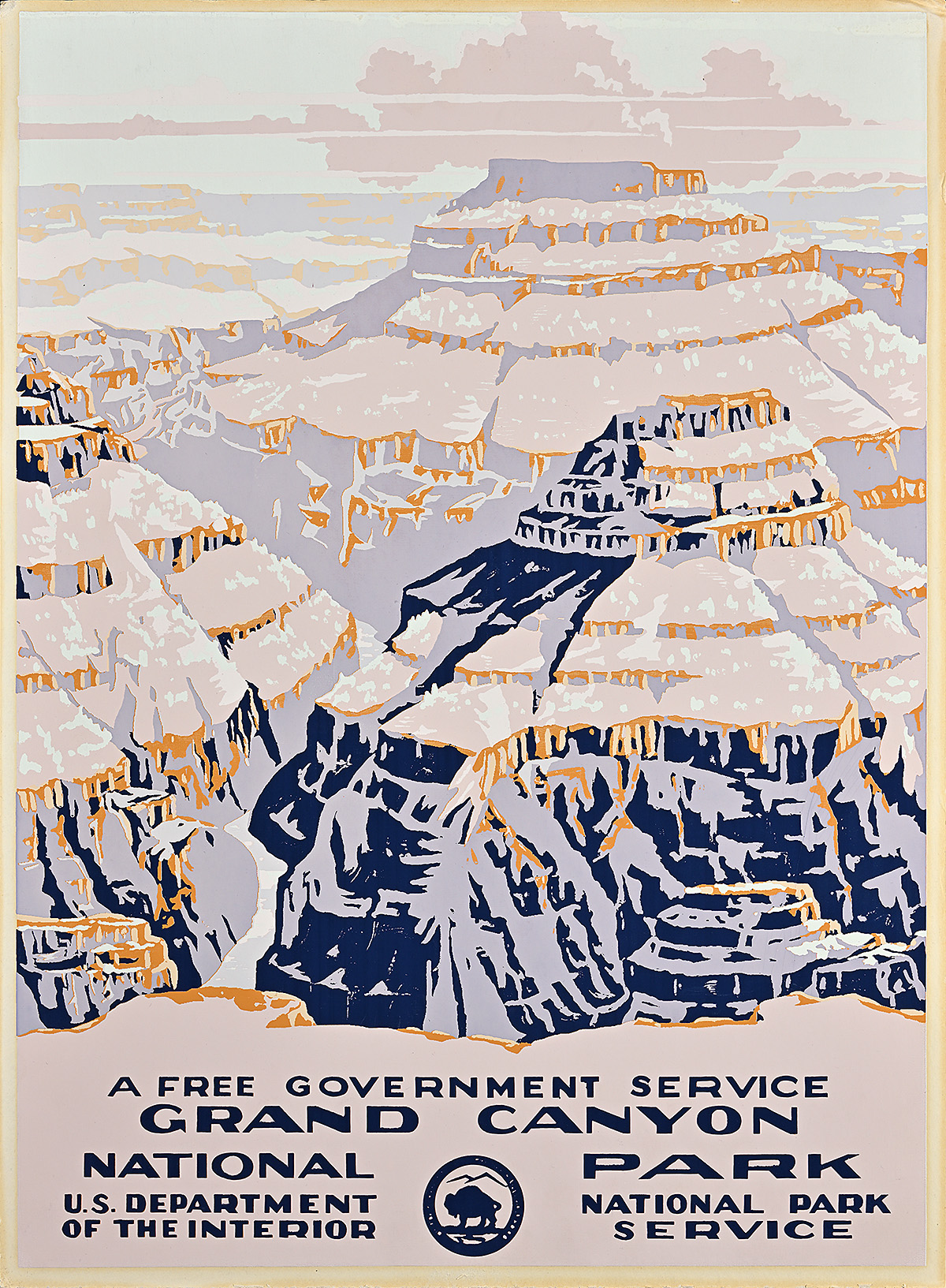

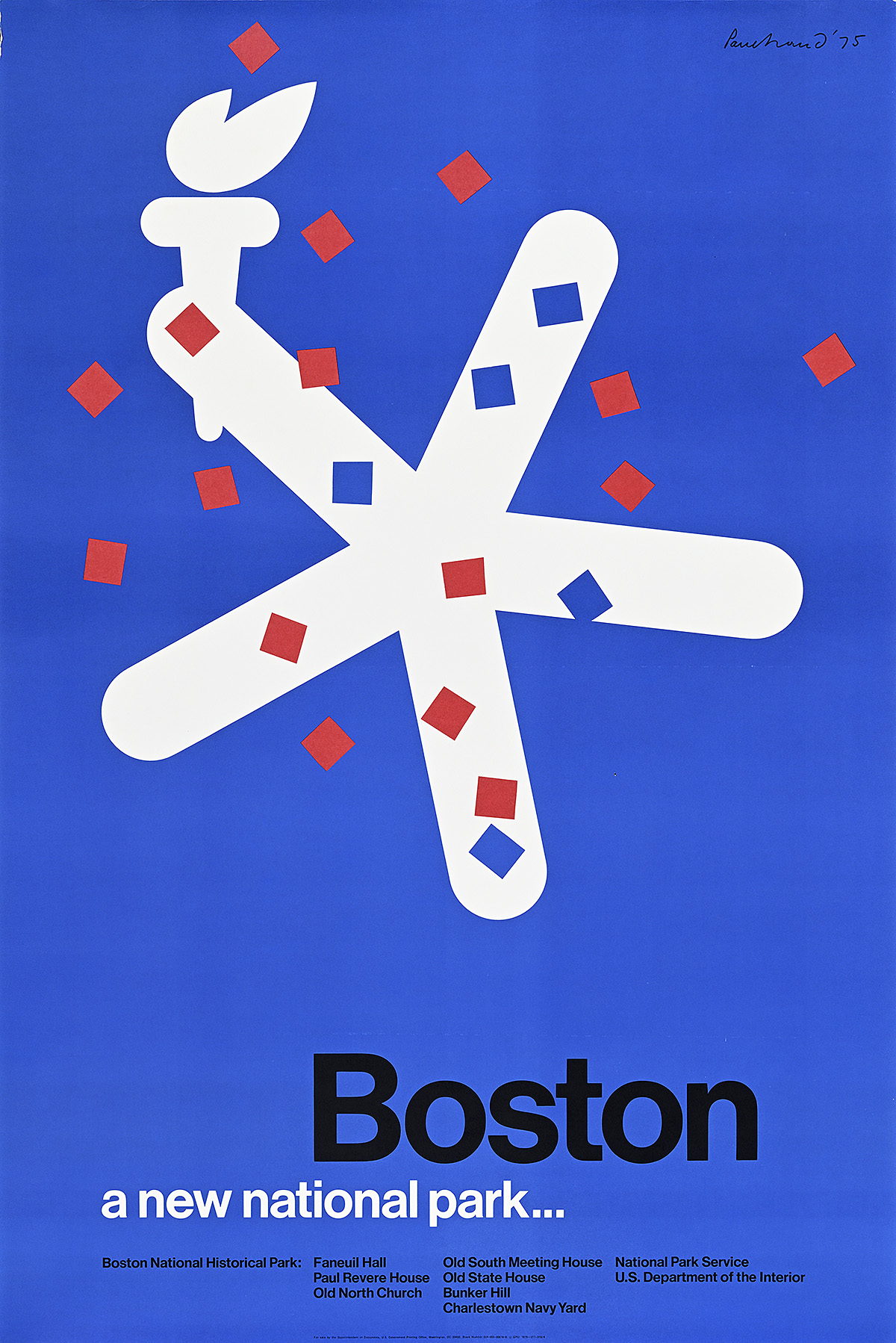

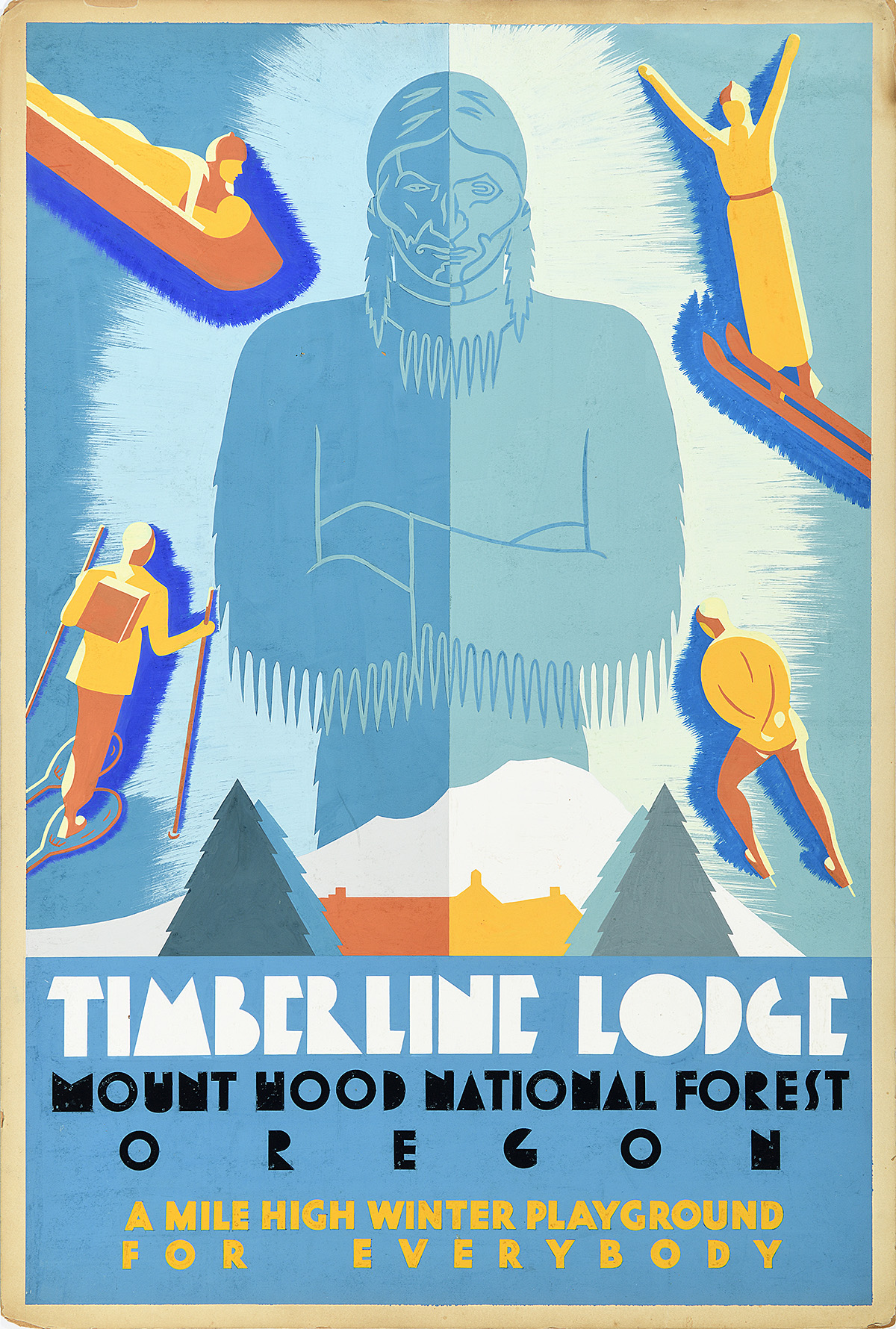

The 17 travel posters Dorothy Waugh created for the National Park Service (NPS) between 1934 and 1936 are significant cultural records of the Great Depression and mark a turning point in American graphic design. Until now, however, there has been little research on them or on their originator. This exhibition, based on private and government documents, is the first dedicated to Waugh and the first to show all of the campaign’s surviving posters.

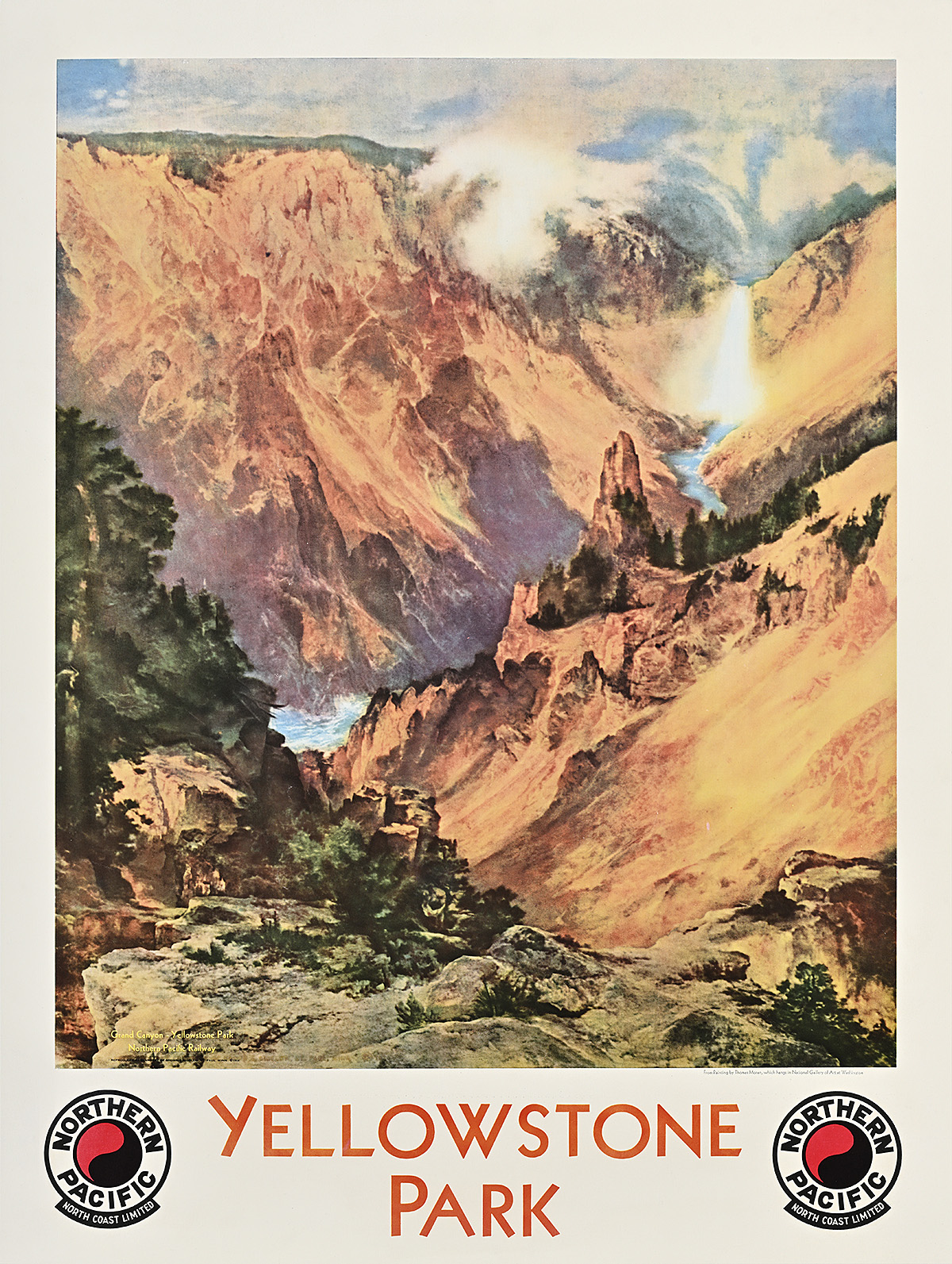

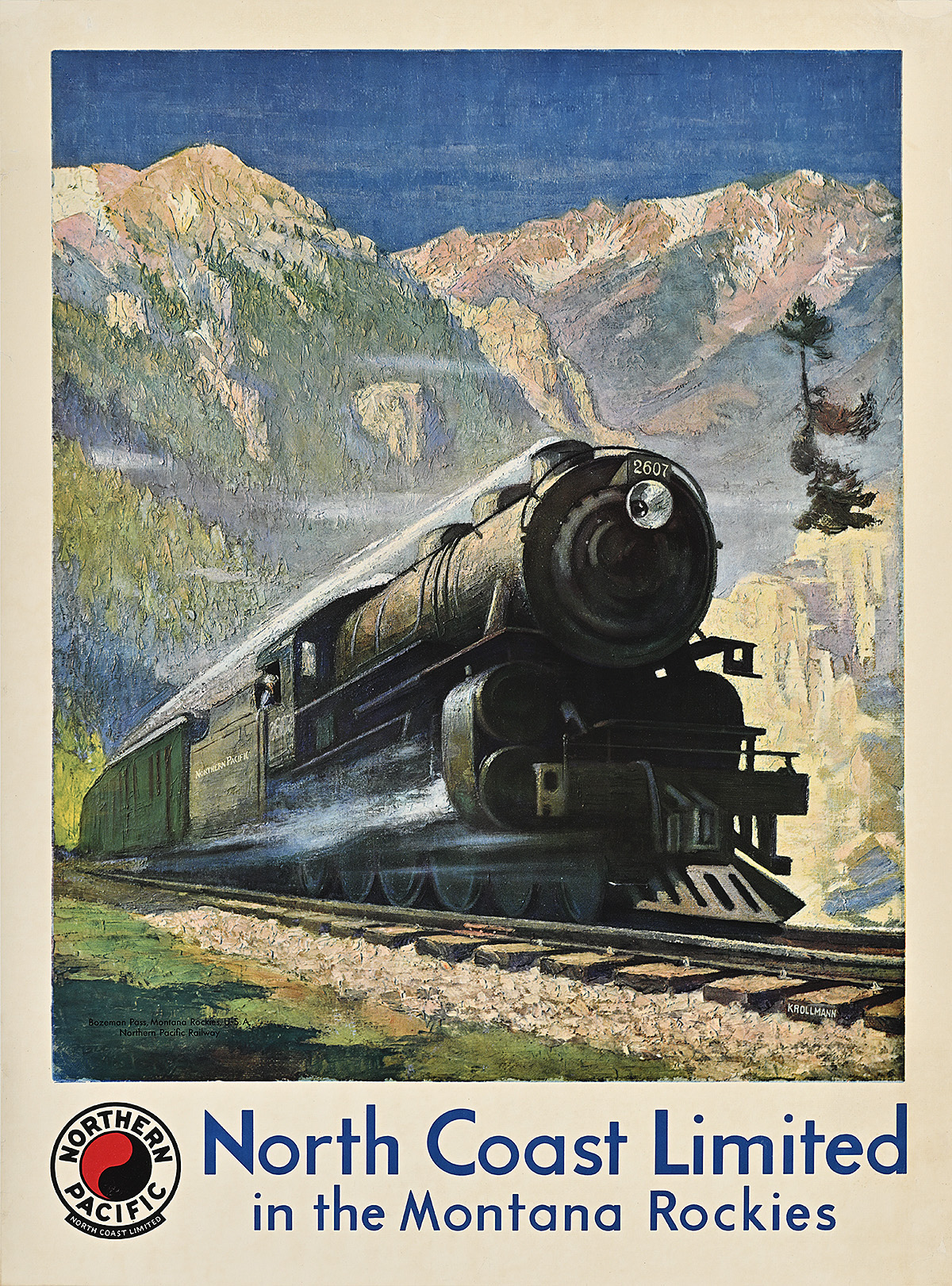

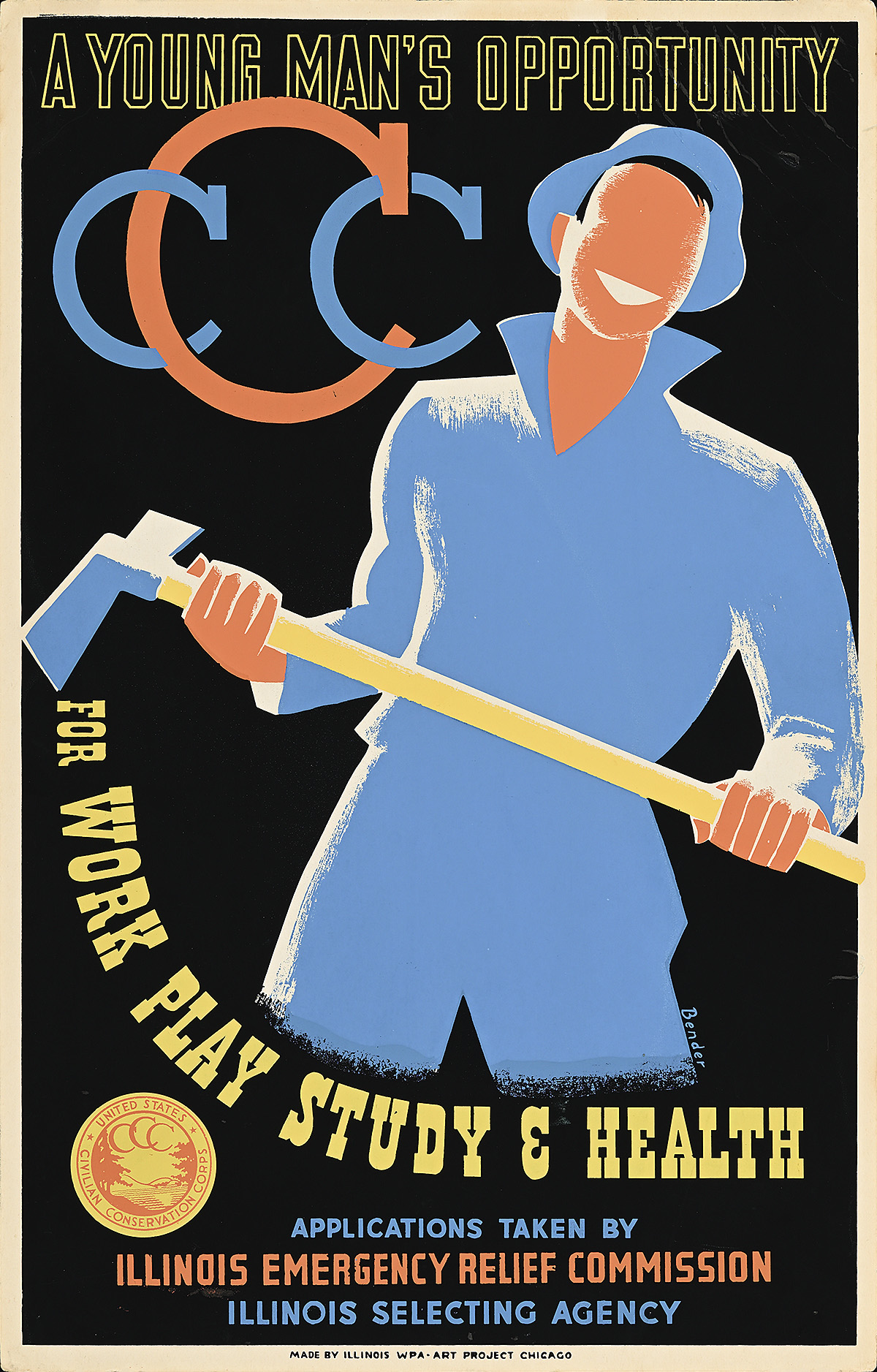

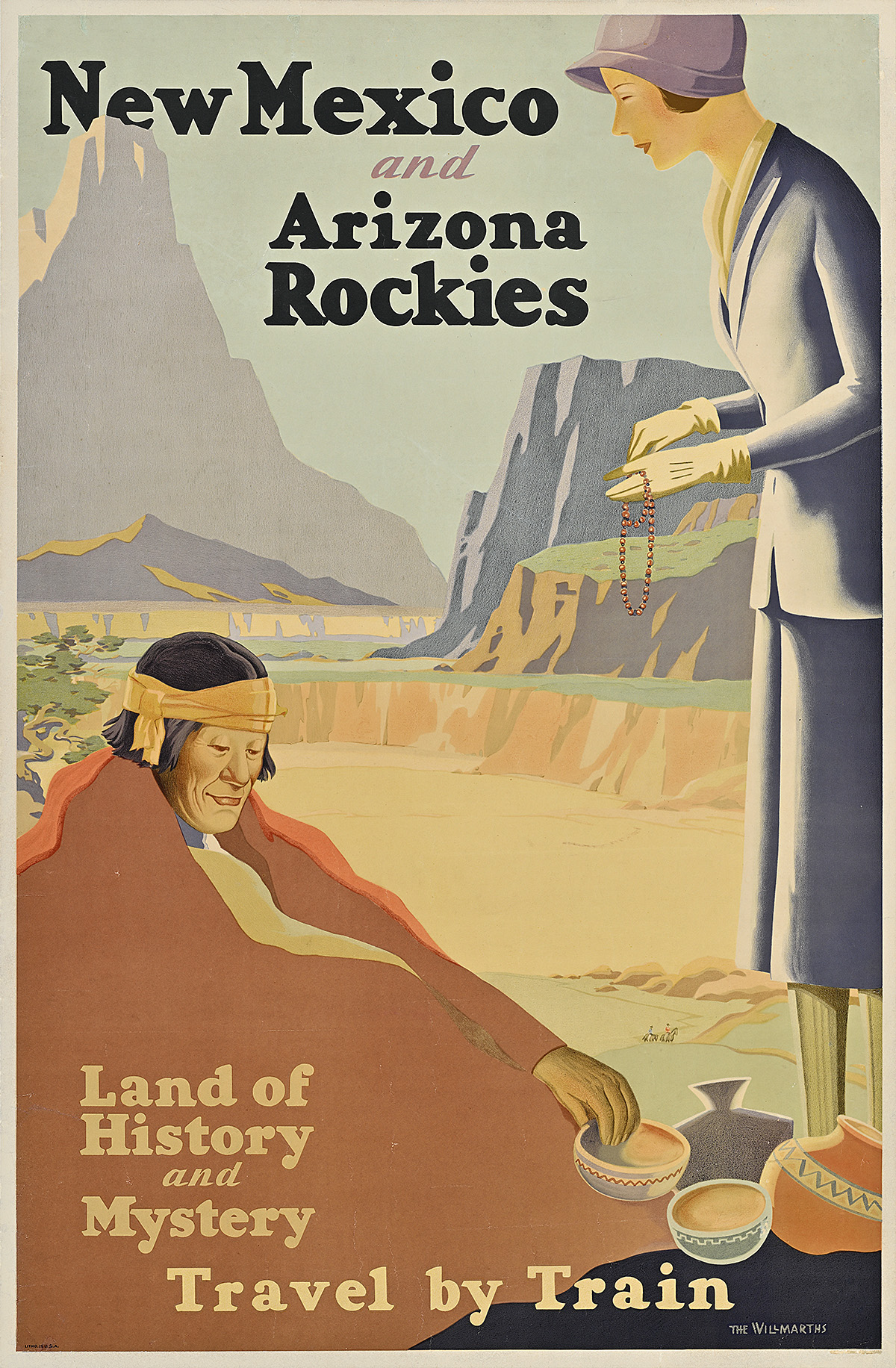

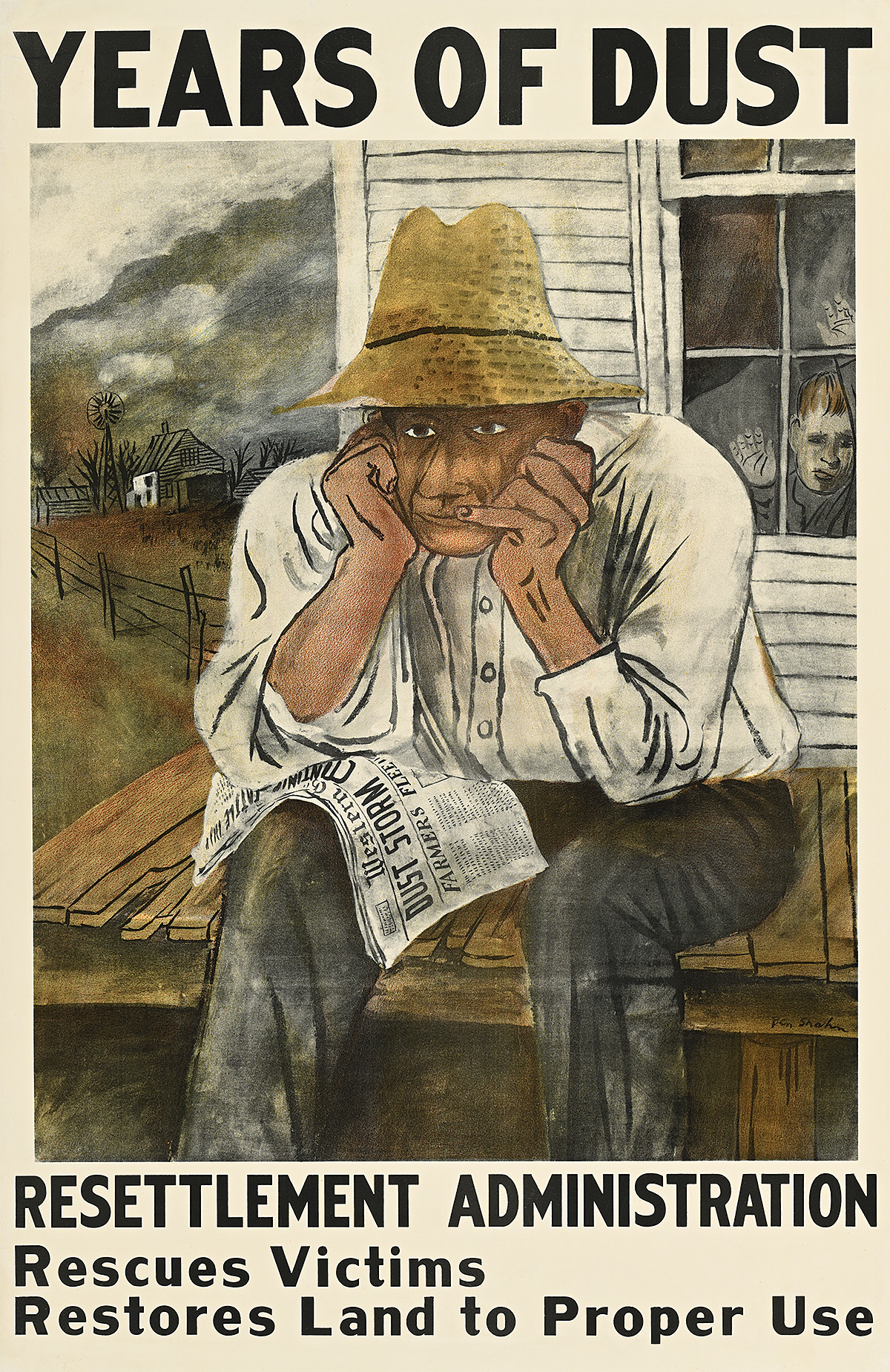

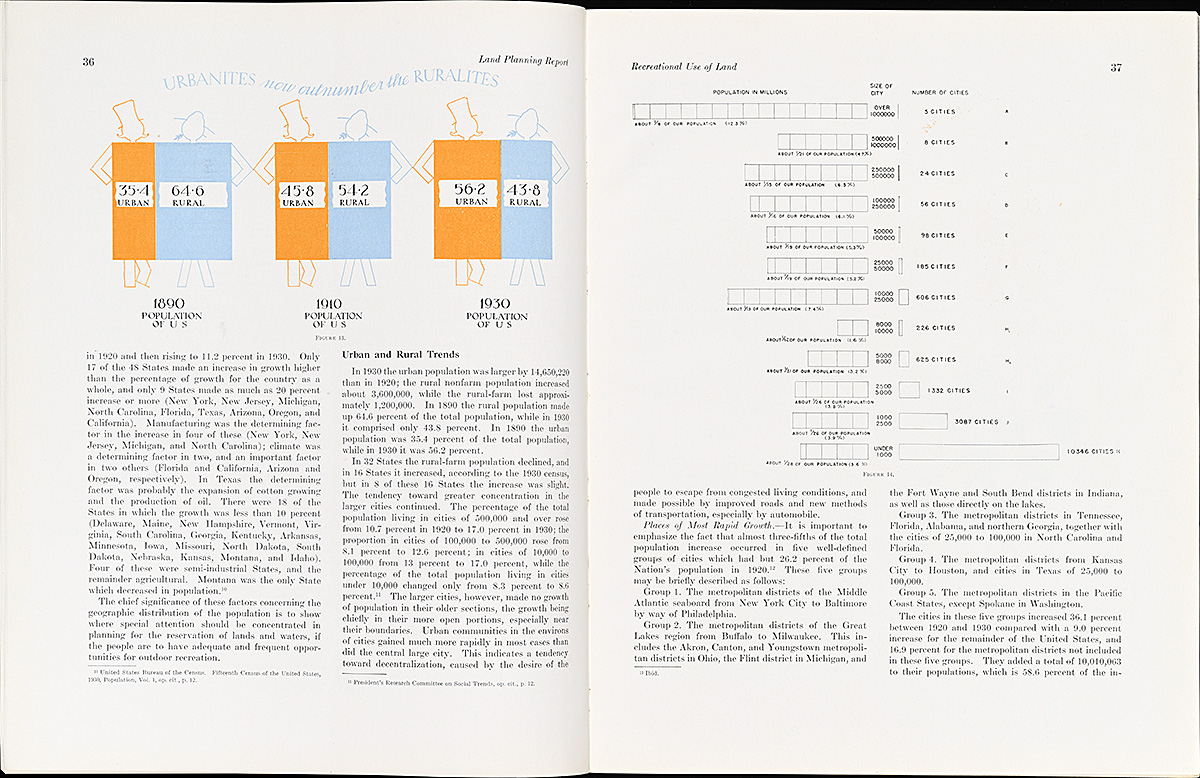

From the 1870s, America’s railroad companies played a critical role in promoting the national parks as tourist destinations in order to increase passenger numbers. Even after the founding of the NPS under President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, the railroads continued to be the main source of such advertising; they issued a steady stream of attractive if conventional posters popularizing the parks and the beautiful landscapes on the routes to them. During the Depression, the parks took on new importance. President Franklin D. Roosevelt invested heavily in park tourism, convinced that it would bolster both the beleaguered nation’s morale and its devastated economy.

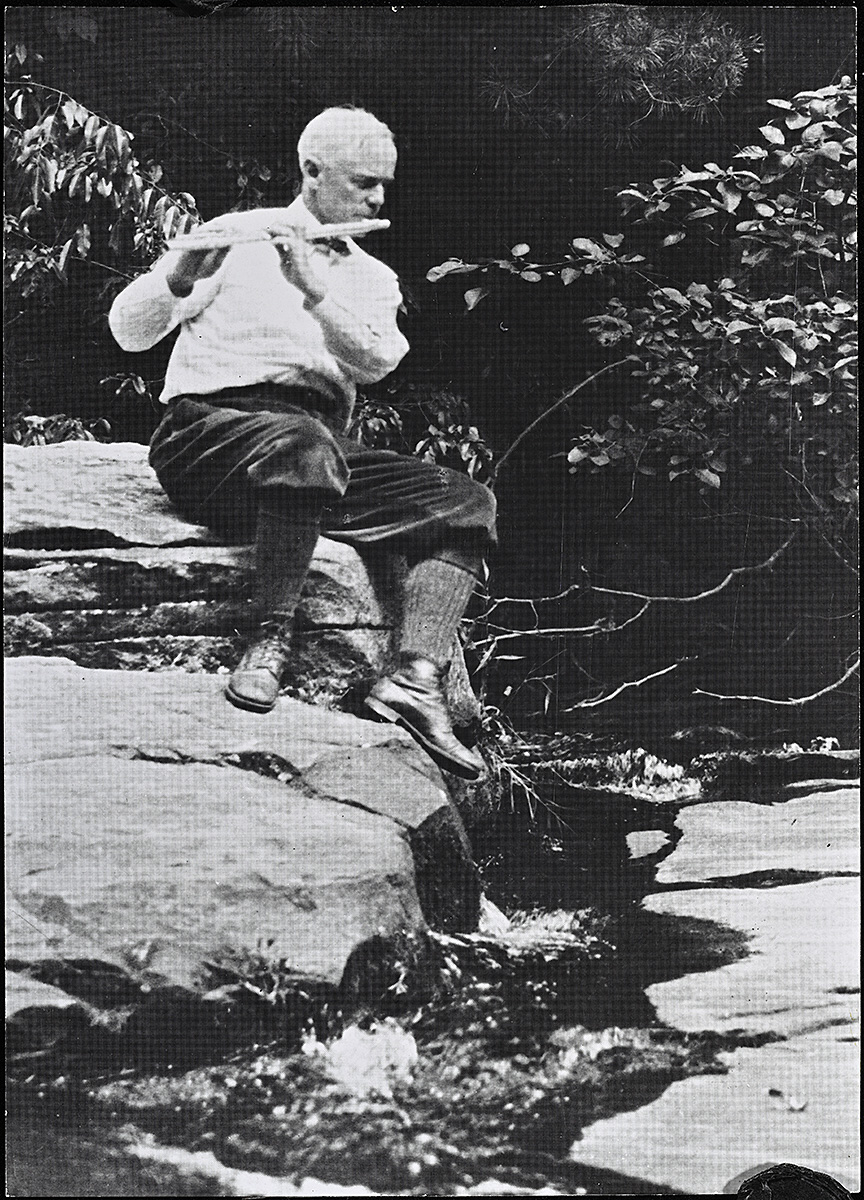

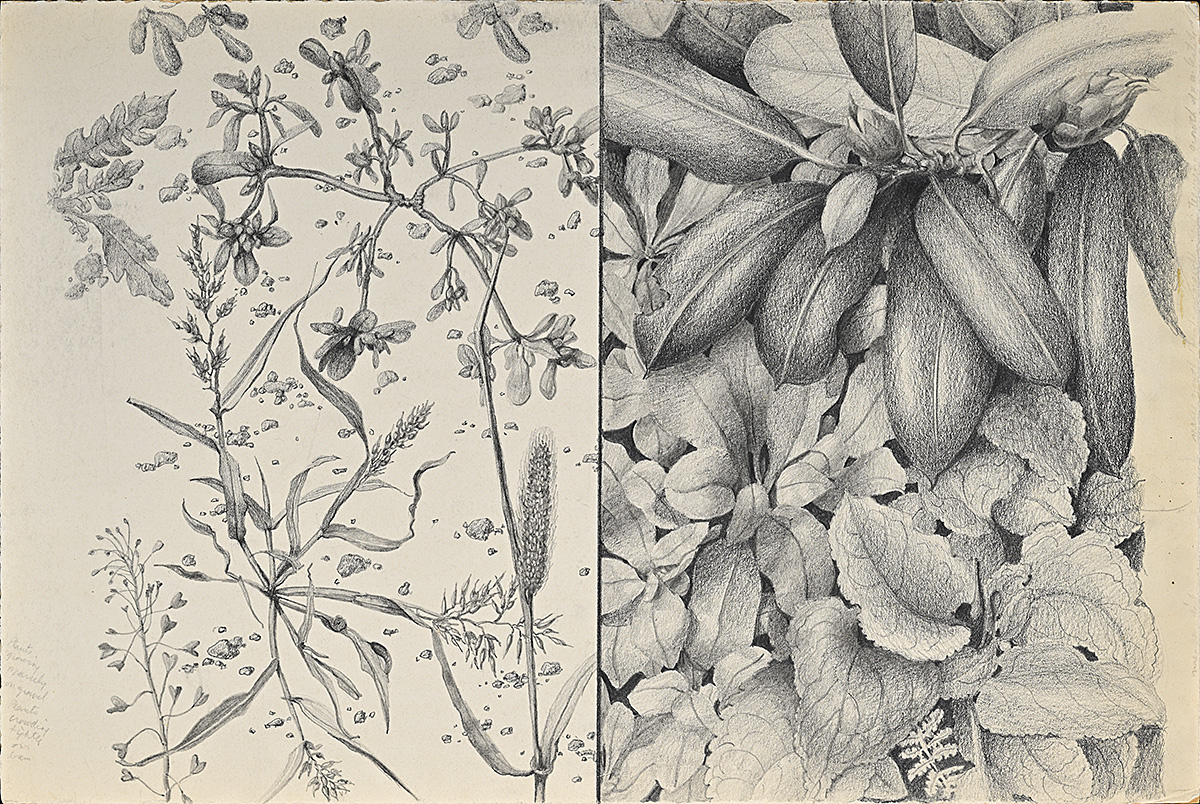

Although Waugh began her work for the NPS in 1933 as a landscape architect, she was also a highly trained artist. She soon advocated for the bureau to produce its own poster campaign, separate from those of the railroads and with its own style and messaging. In 1934, the Roosevelt administration launched National Parks Year, a public-relations initiative that included money for the campaign, whose design was entrusted to Waugh. It was the first time the government had assigned such an ambitious project to a single designer, let alone a female modernist. Waugh also received the backing of her very senior male supervisor at the NPS, who was well aware of her artistic talent. The resulting series of posters, at once avant-garde and accessible, put Waugh at the forefront of the government’s increasingly expansive presence in American visual culture.

Large text, Spanish translation, and a Plain Language summary are available via the QR code and at the Info Desk.

El texto con letra grande, la traducción al español y un resumen en lectura fácil están disponibles a través del código QR y en atención al público.