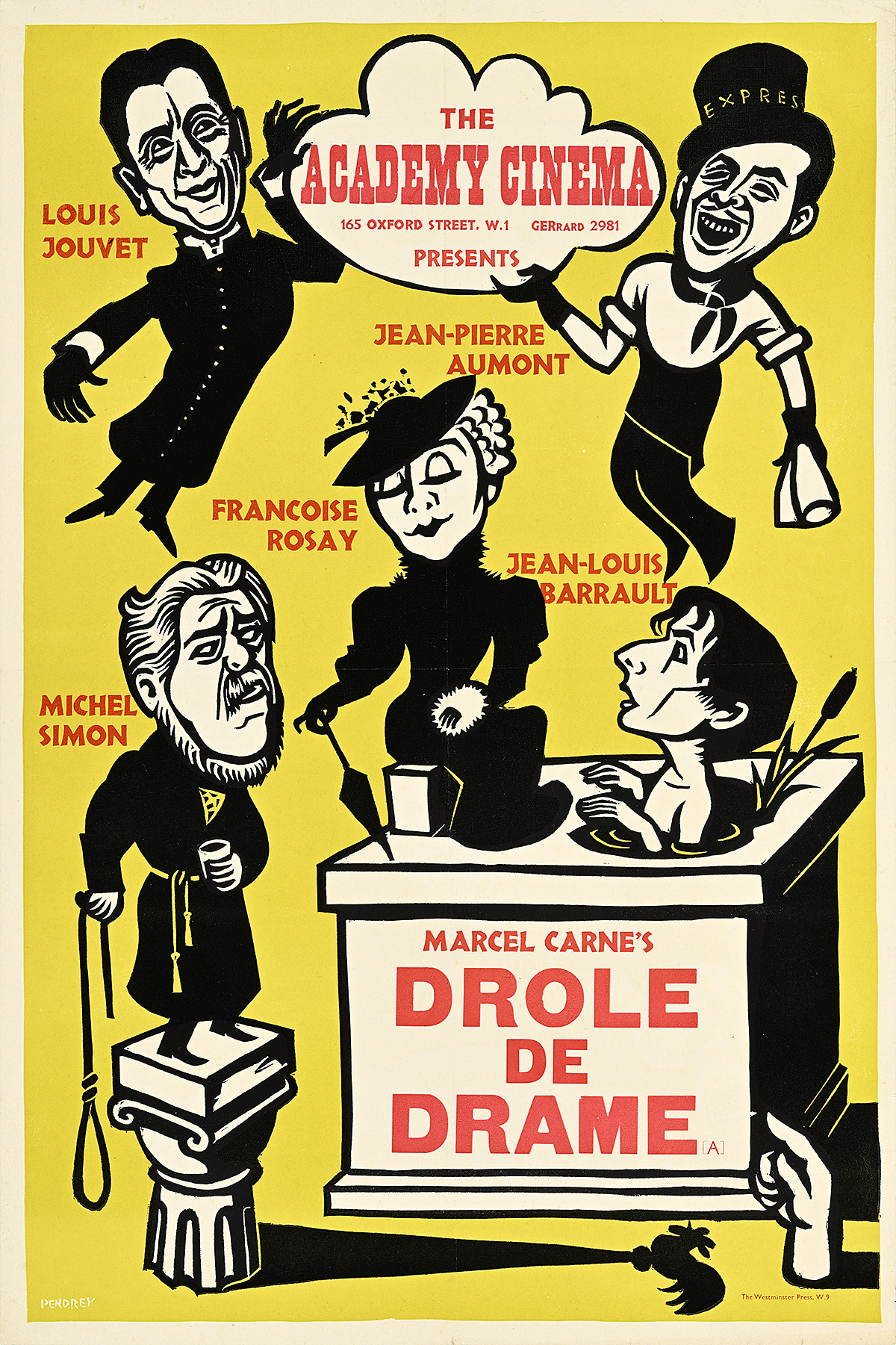

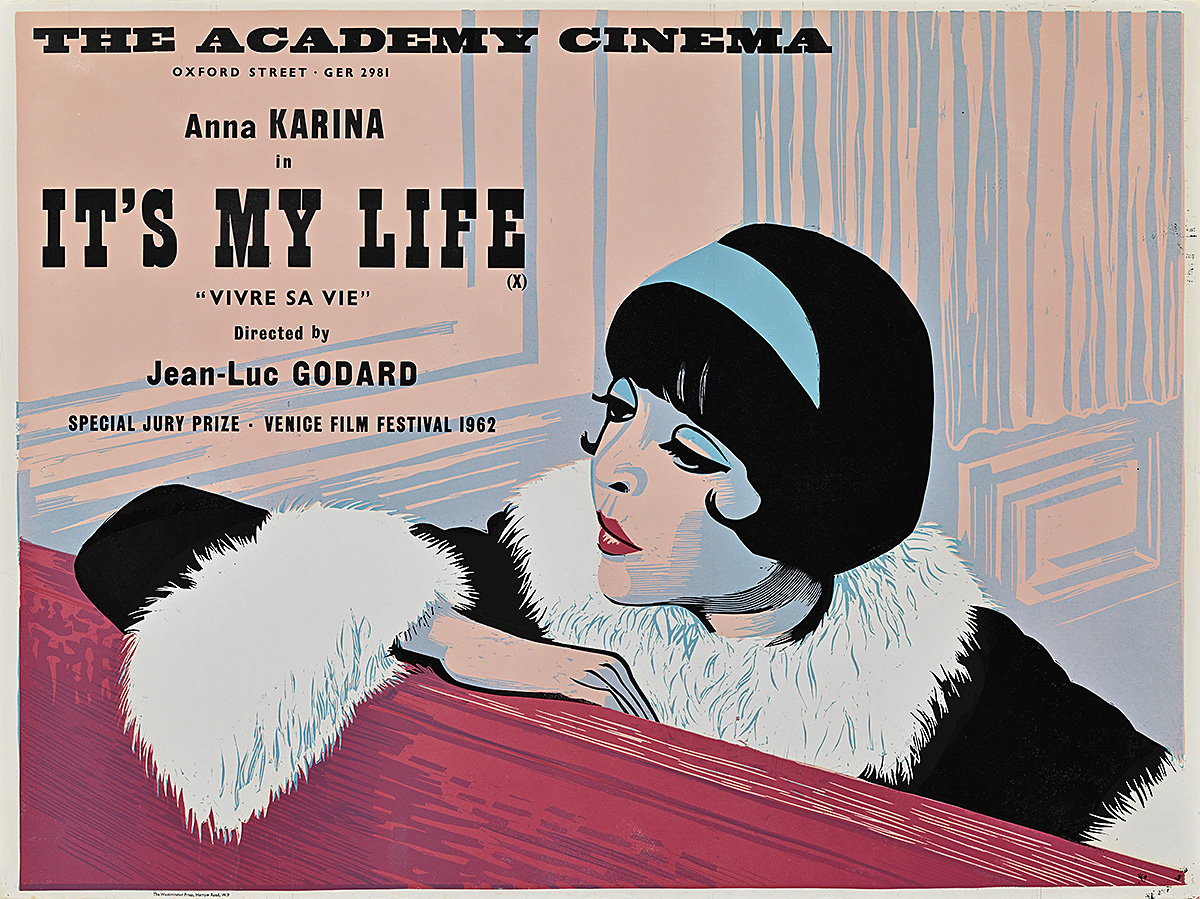

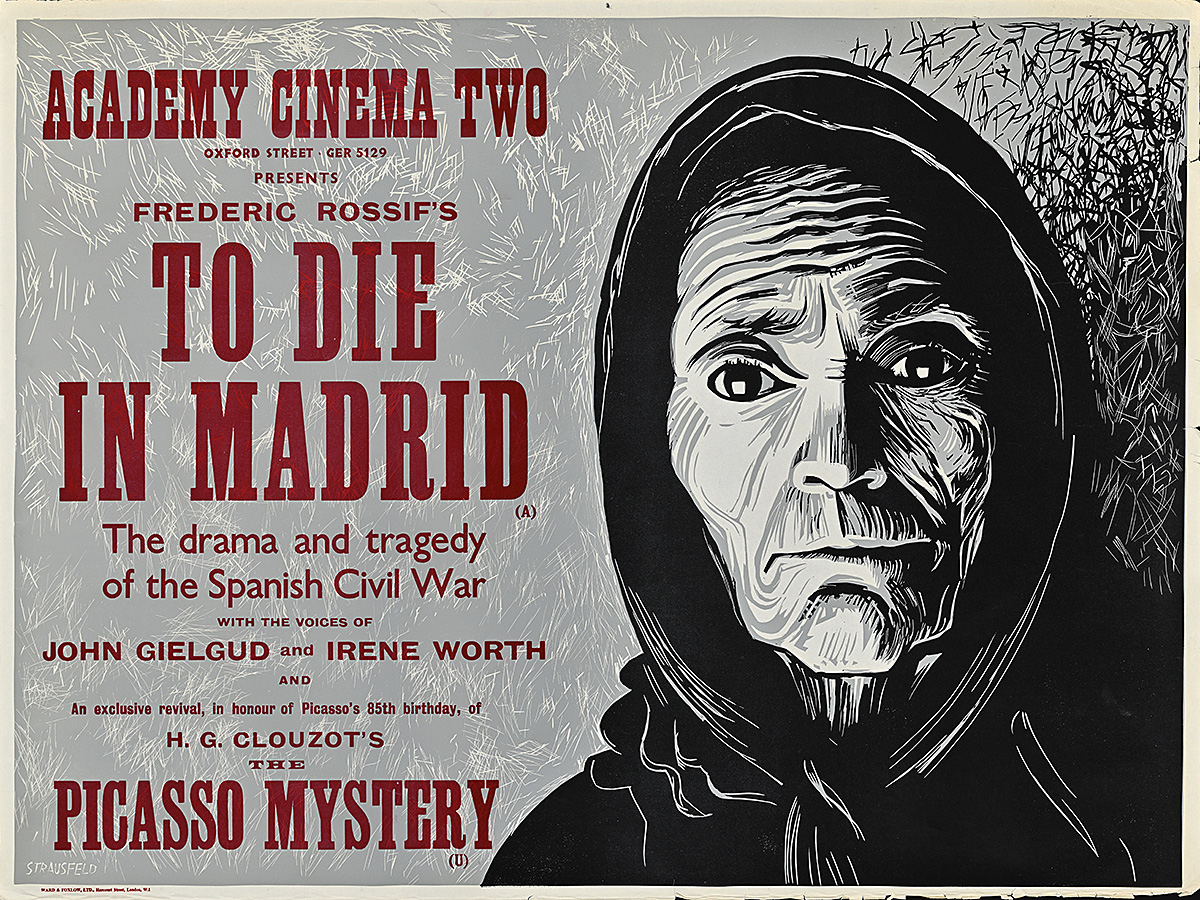

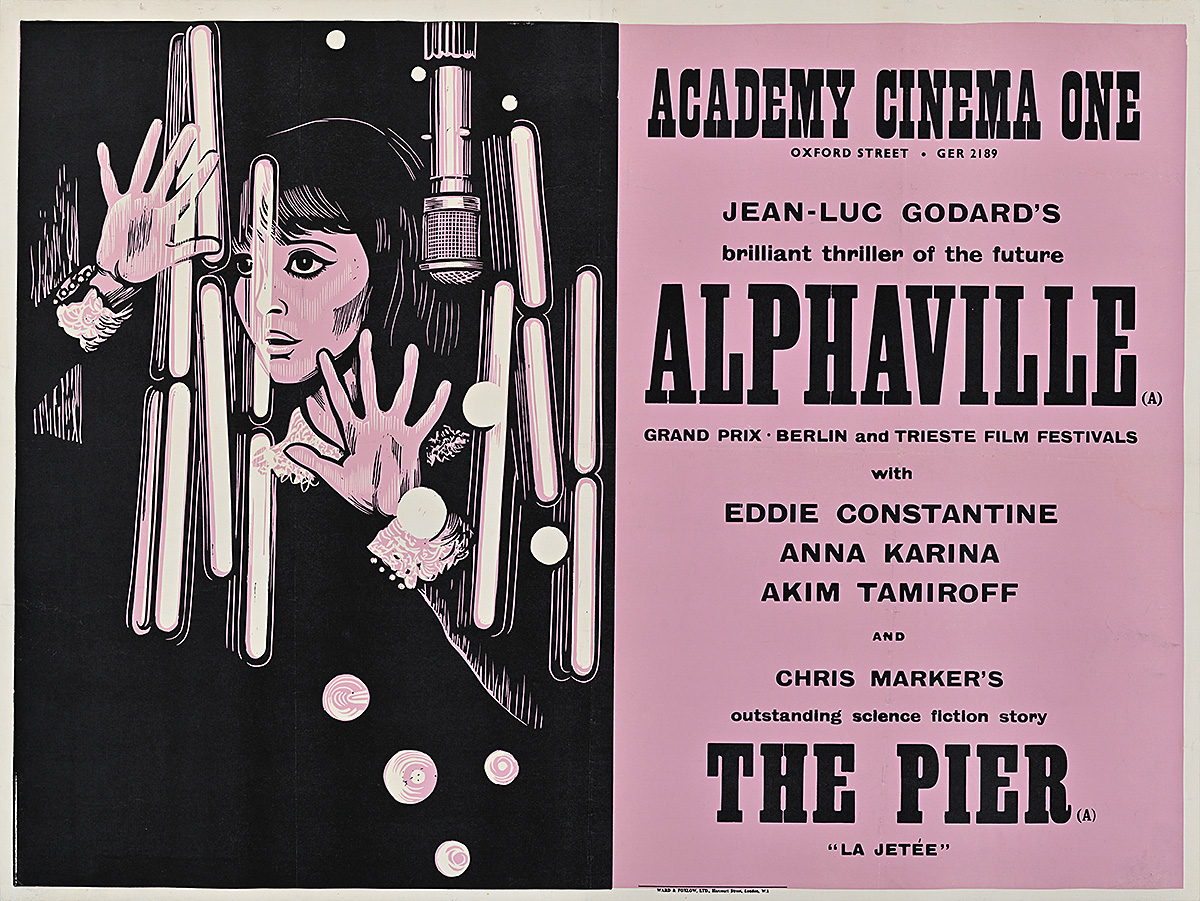

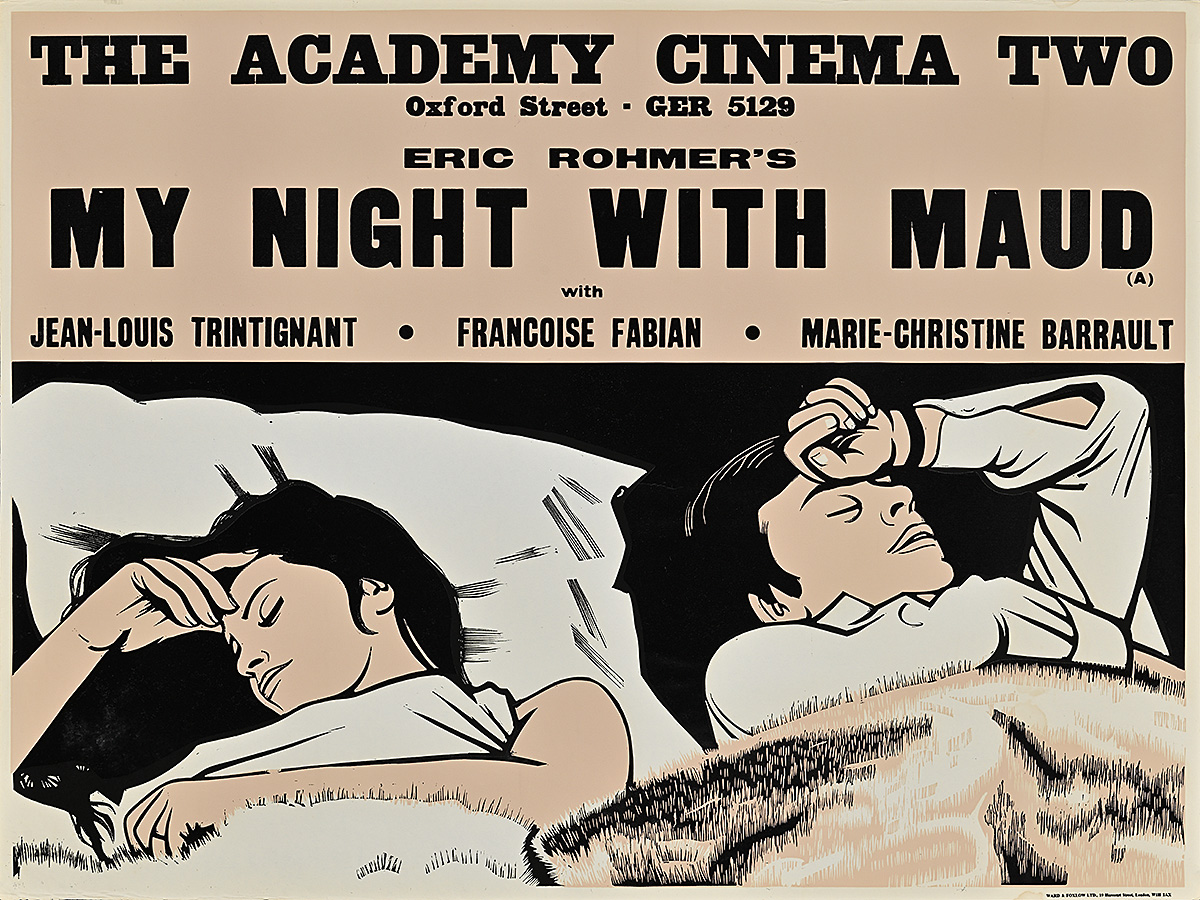

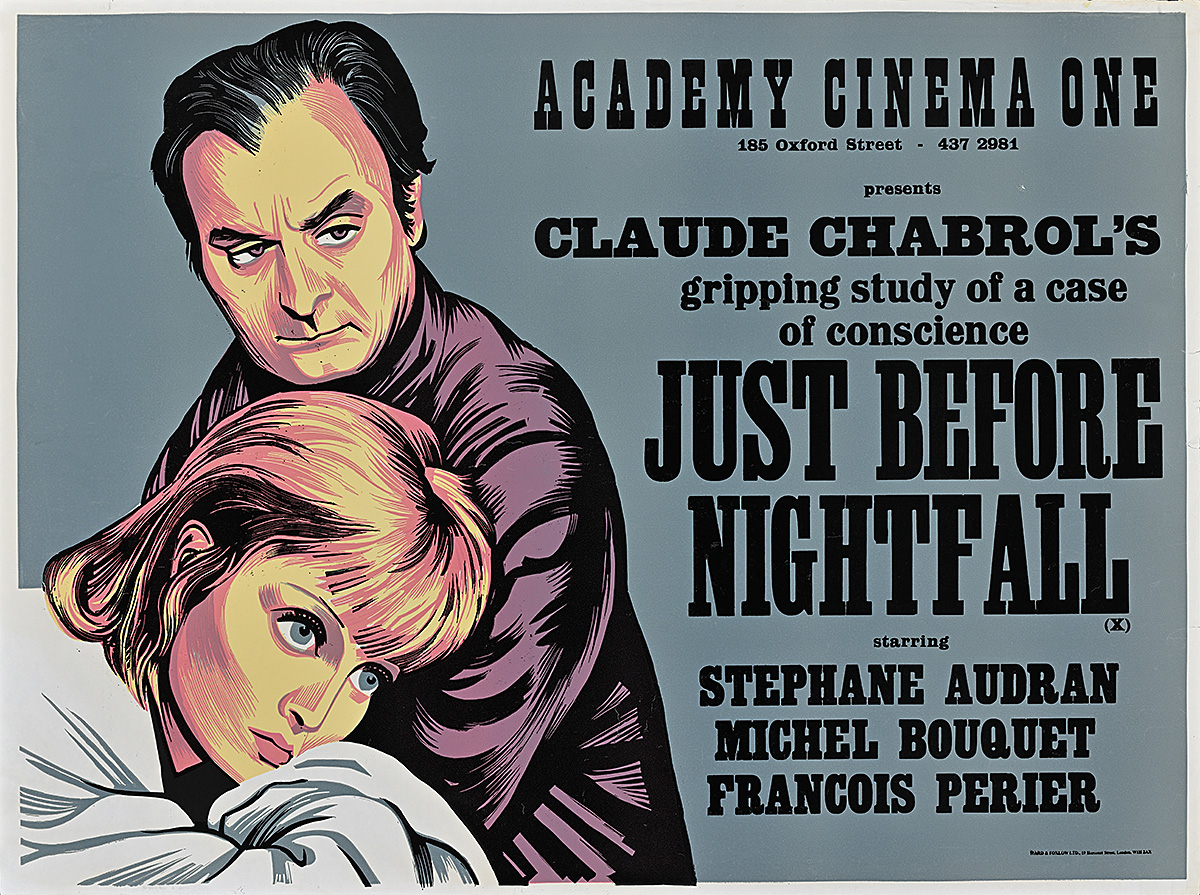

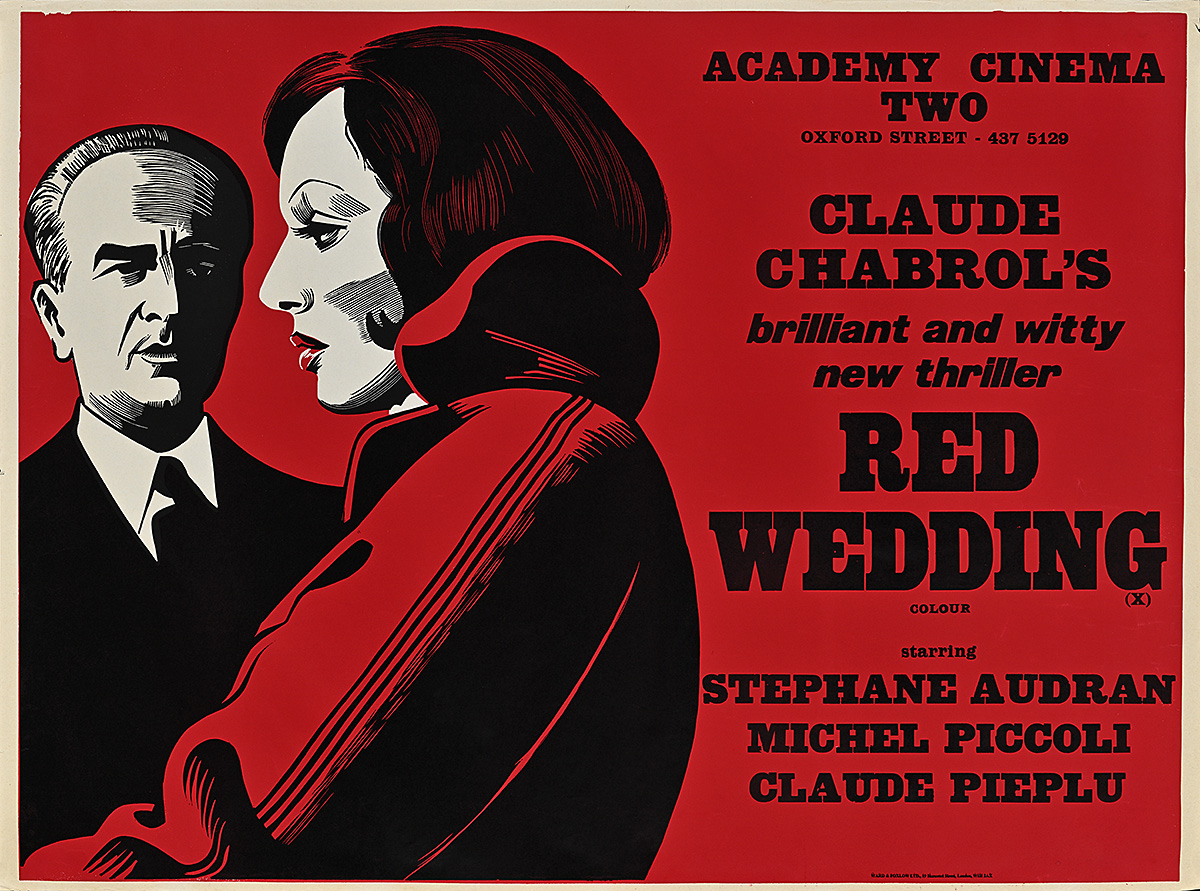

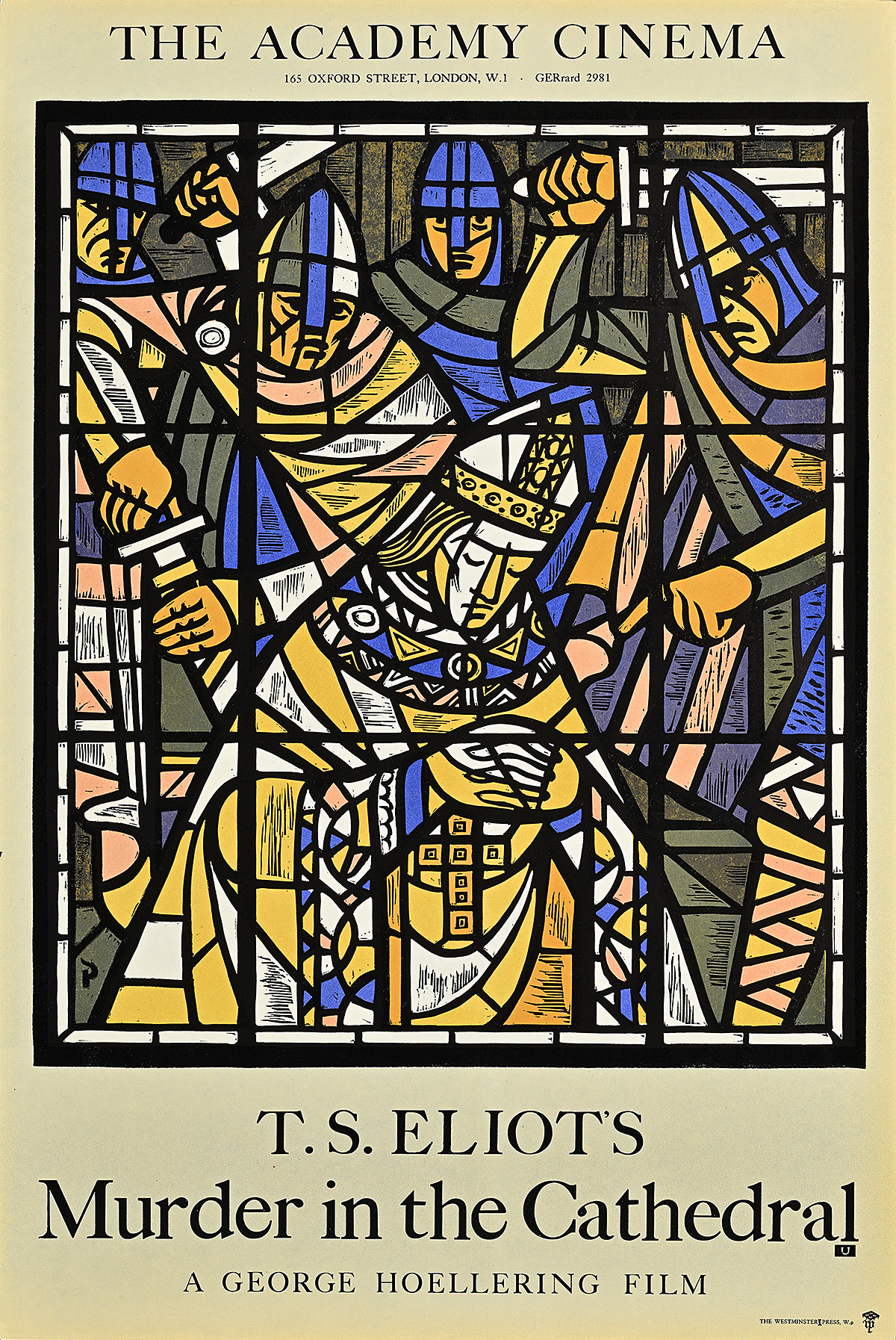

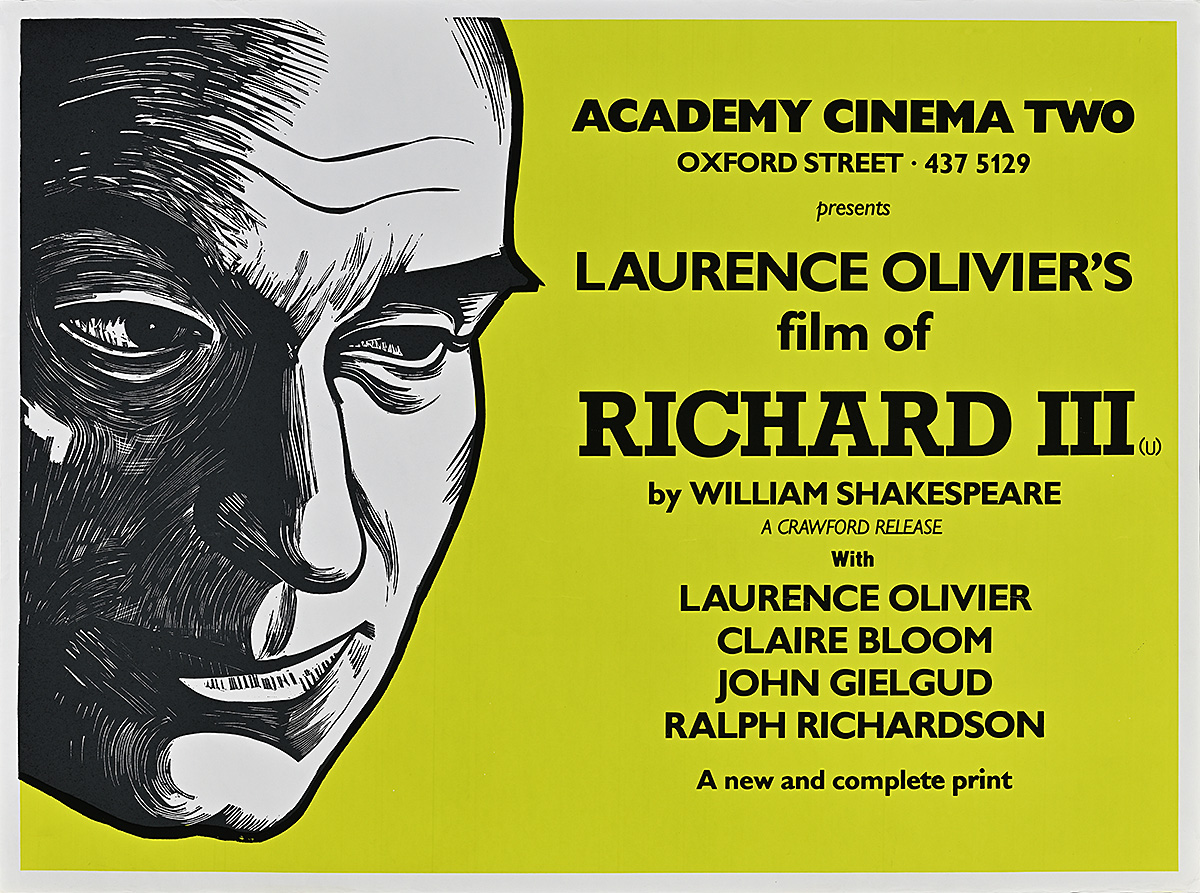

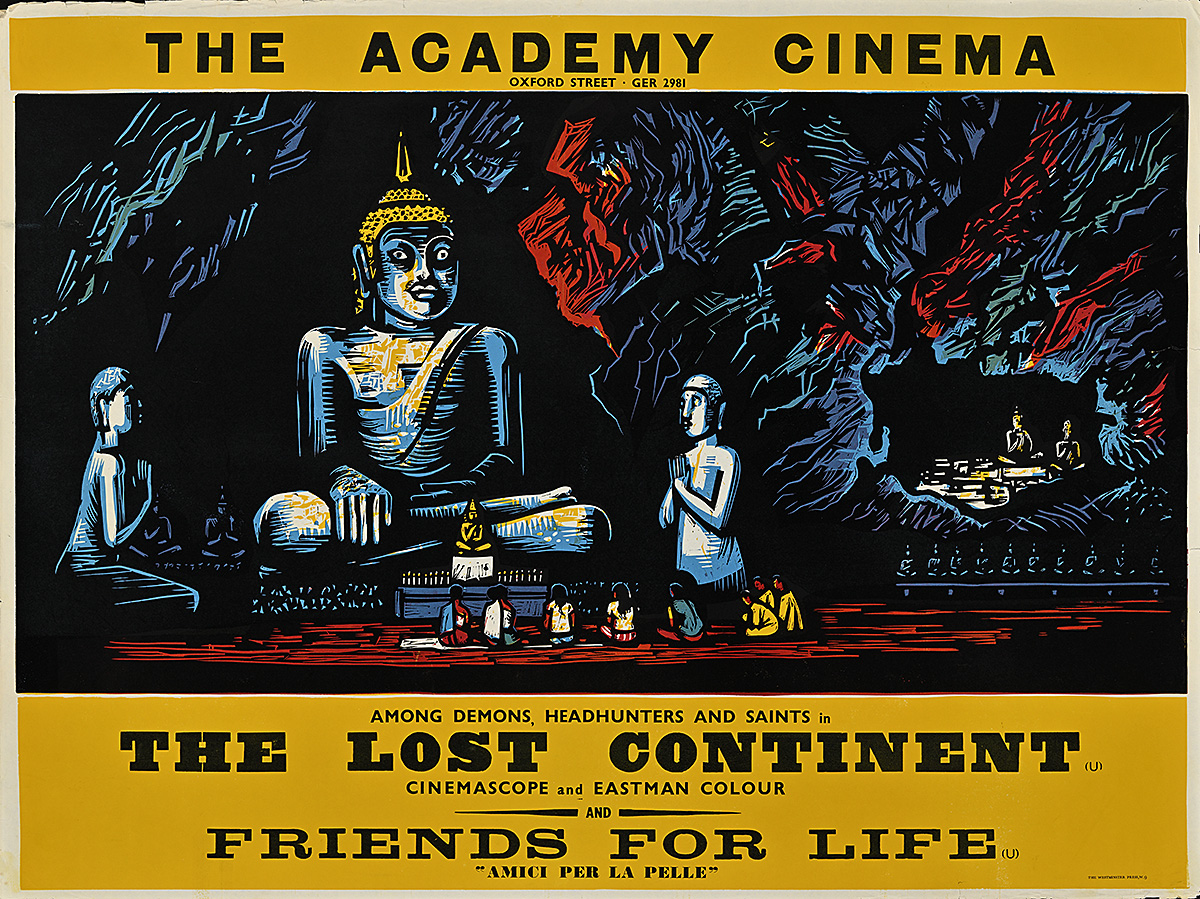

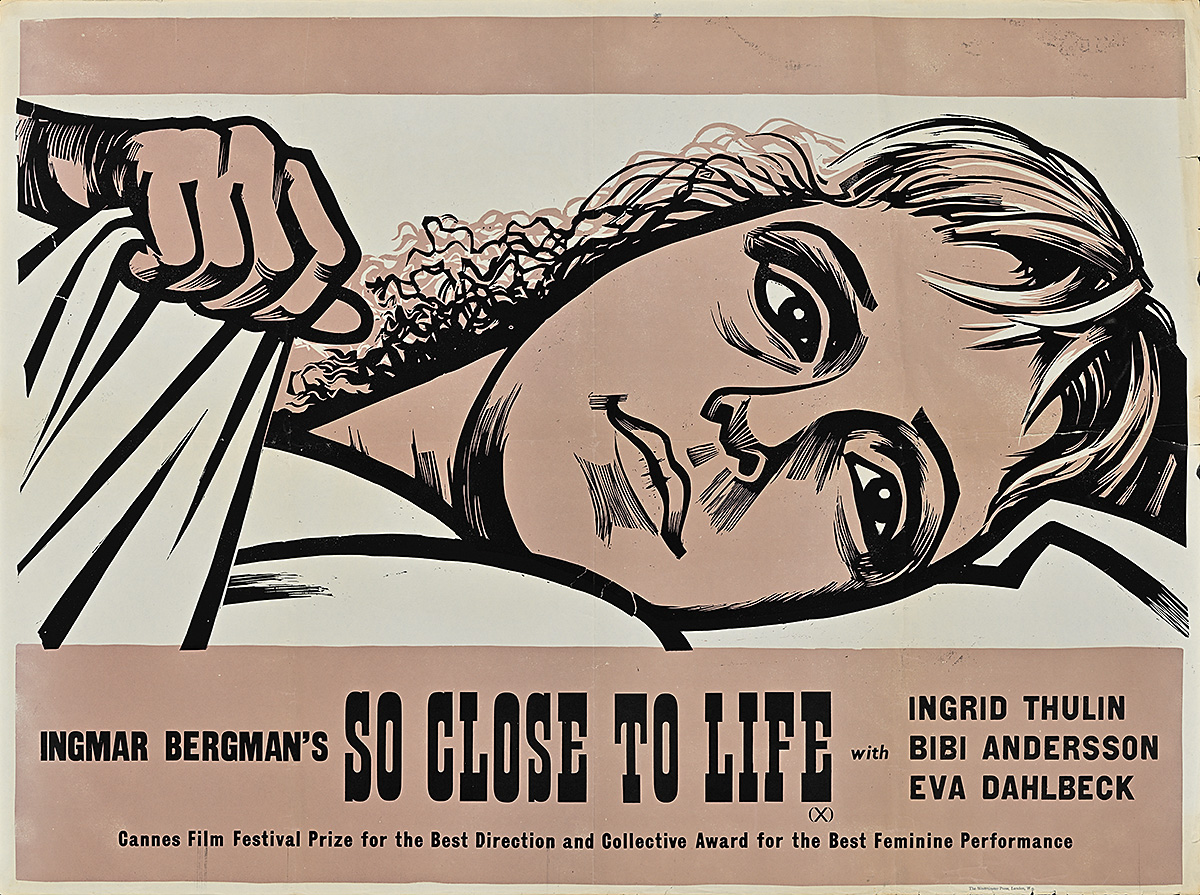

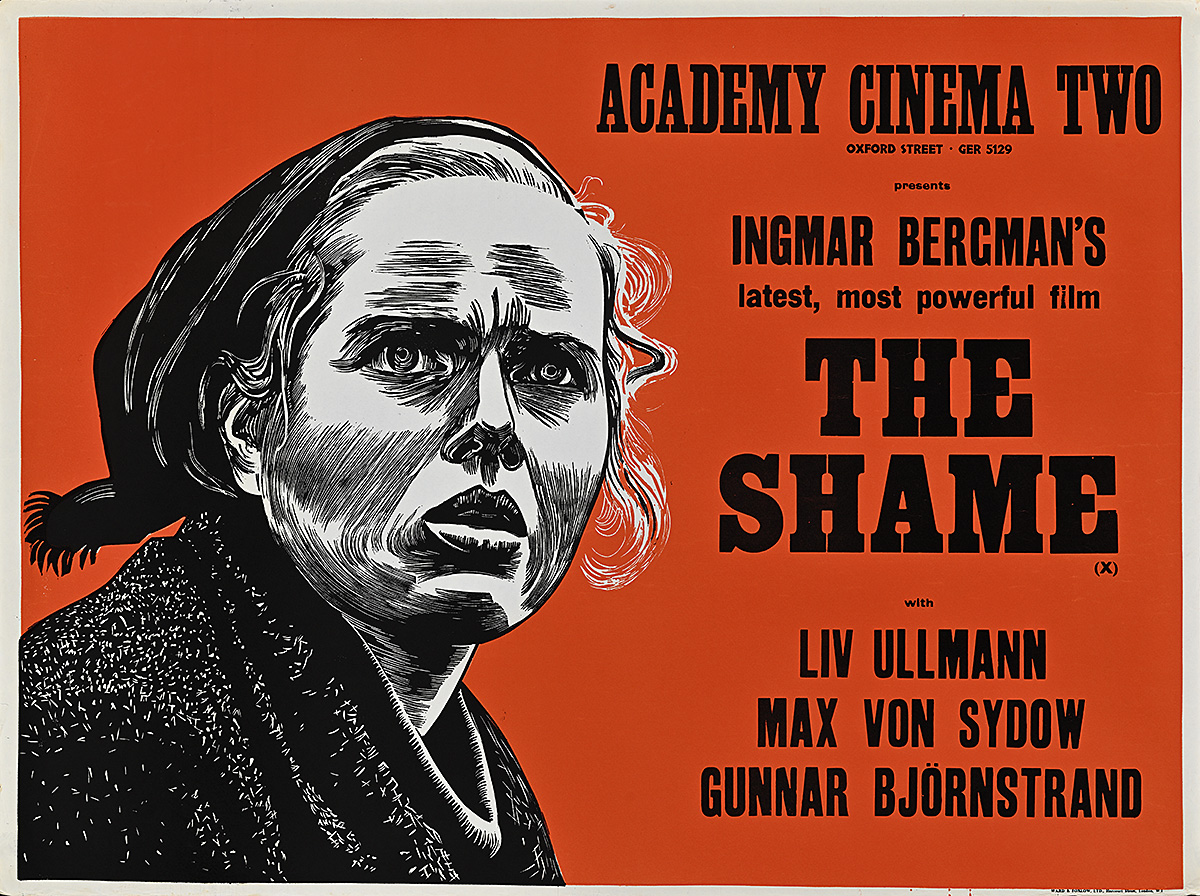

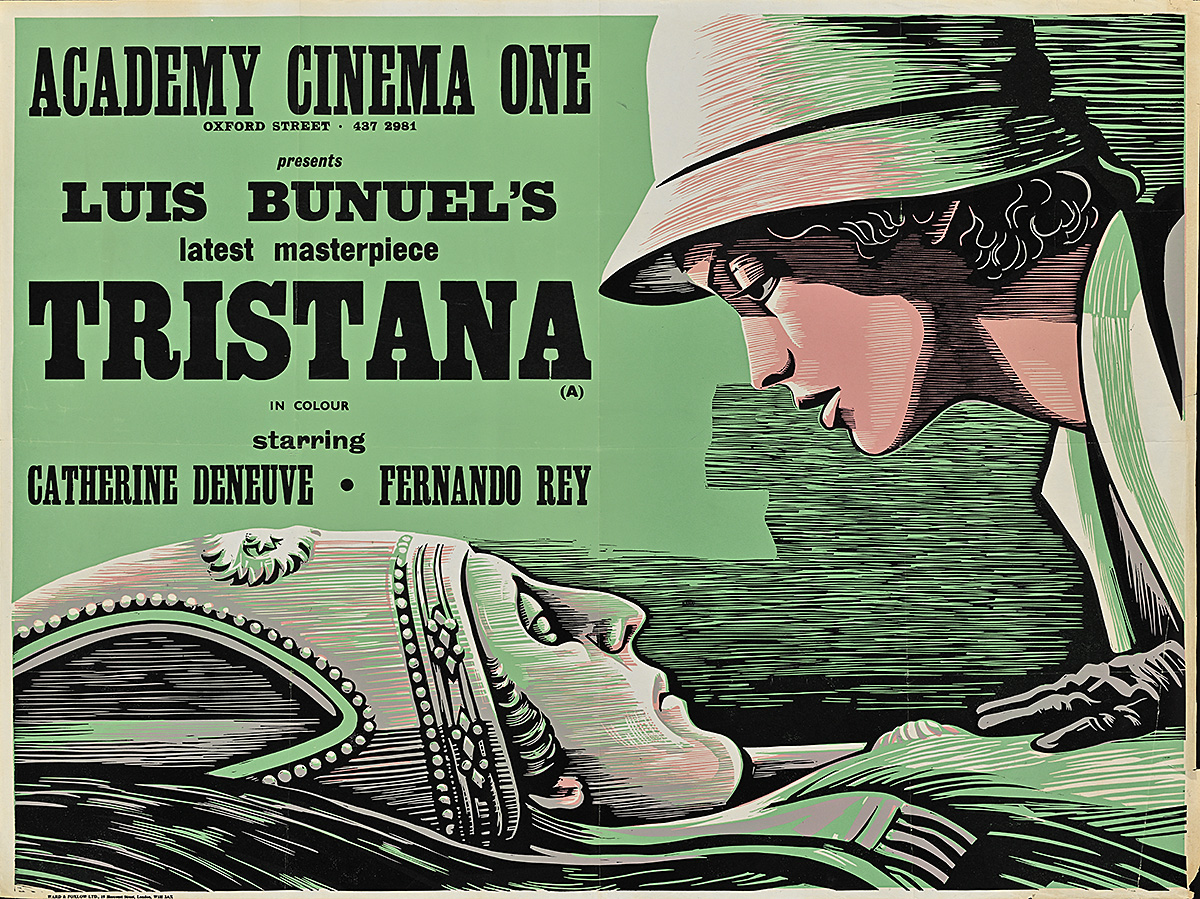

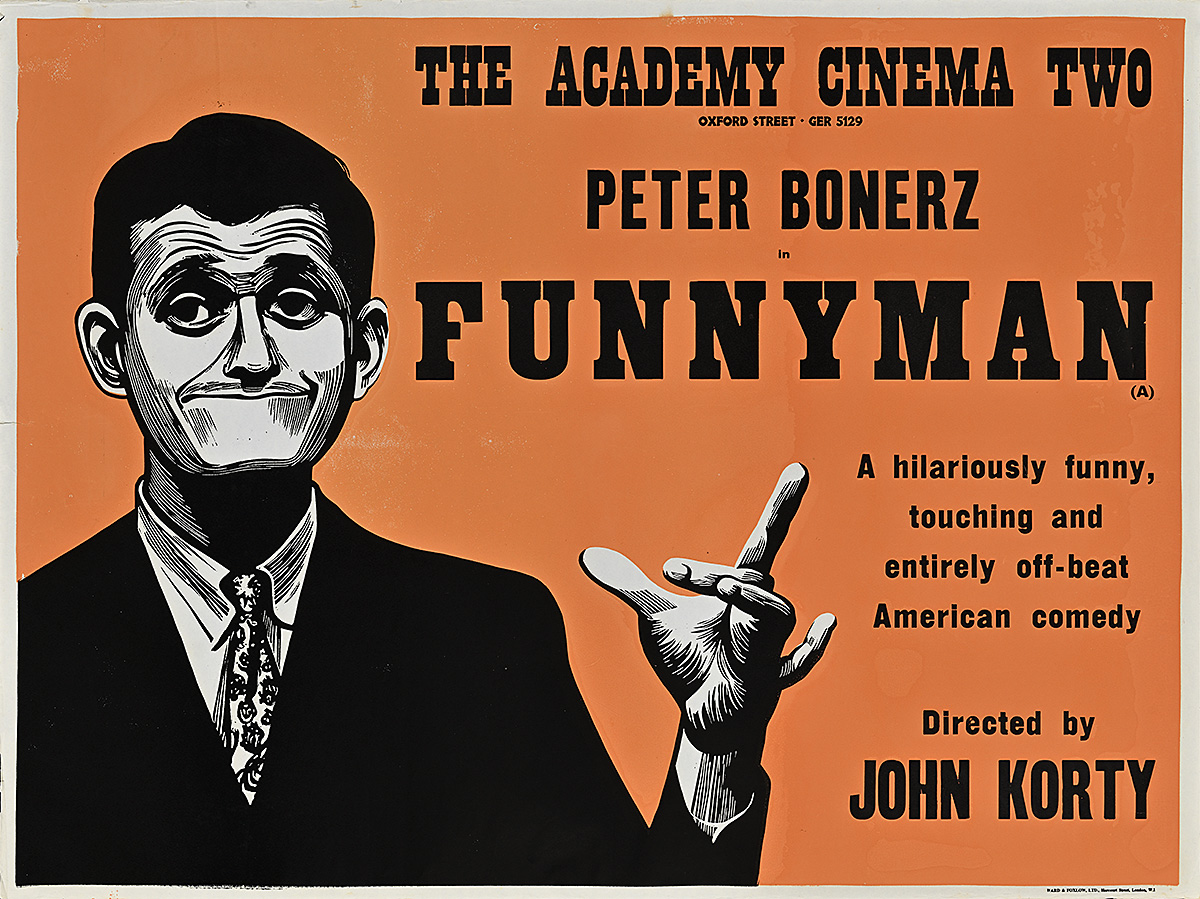

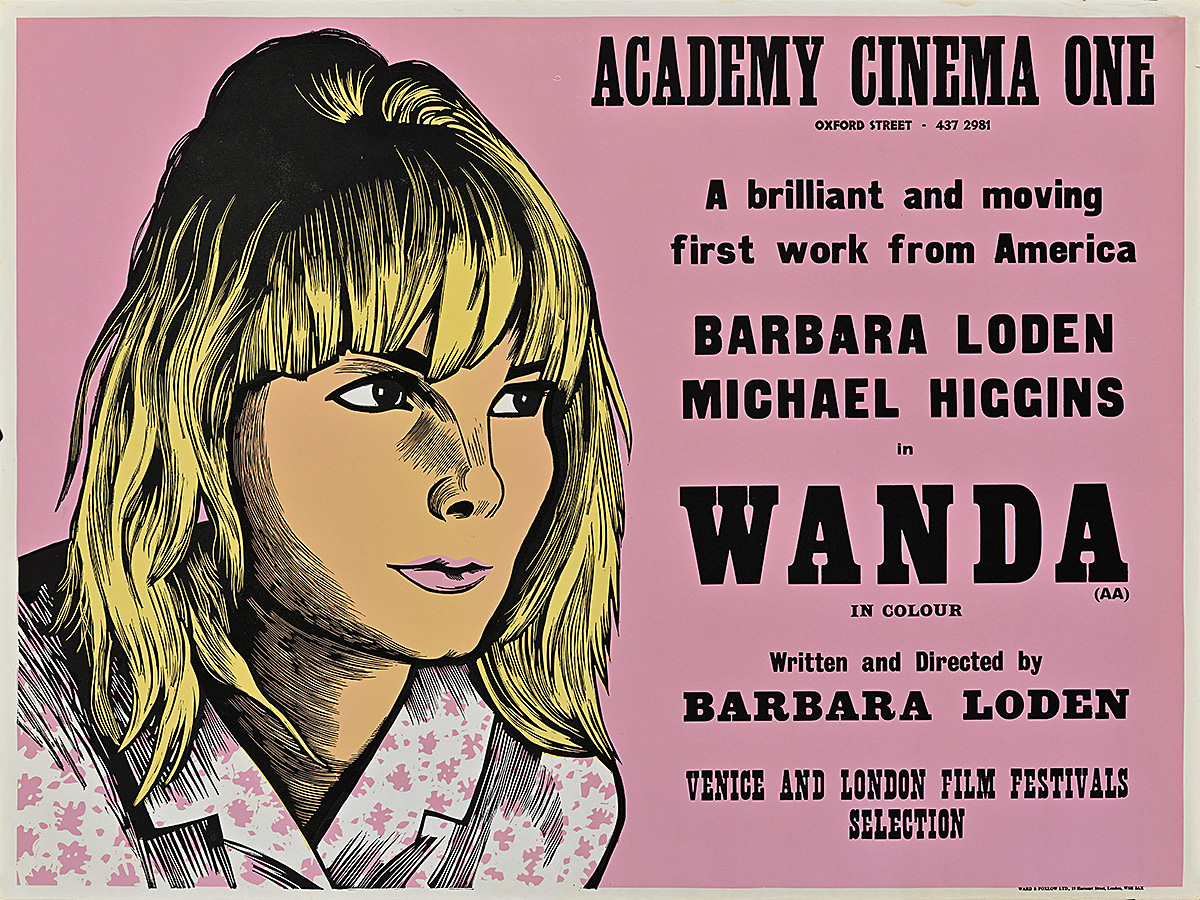

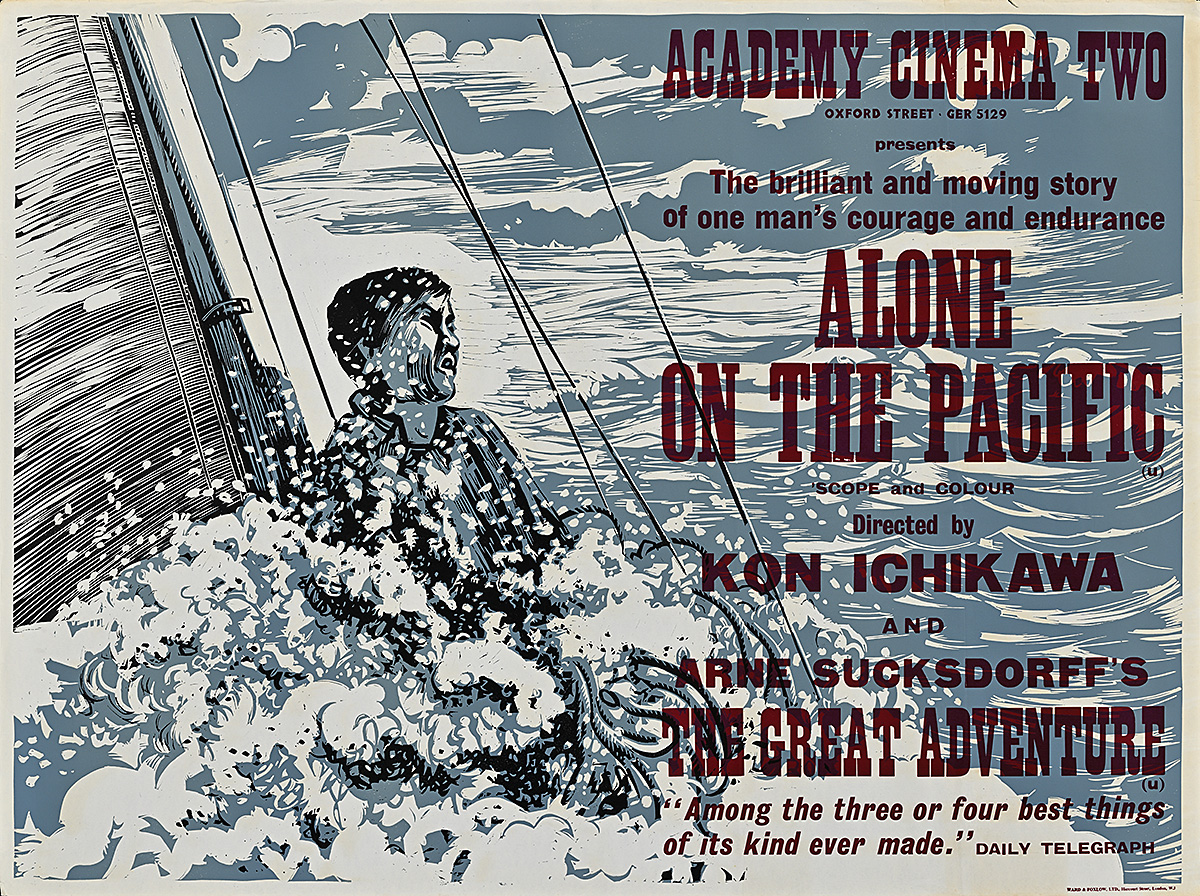

Art for Art House: The Posters of Peter Strausfeld

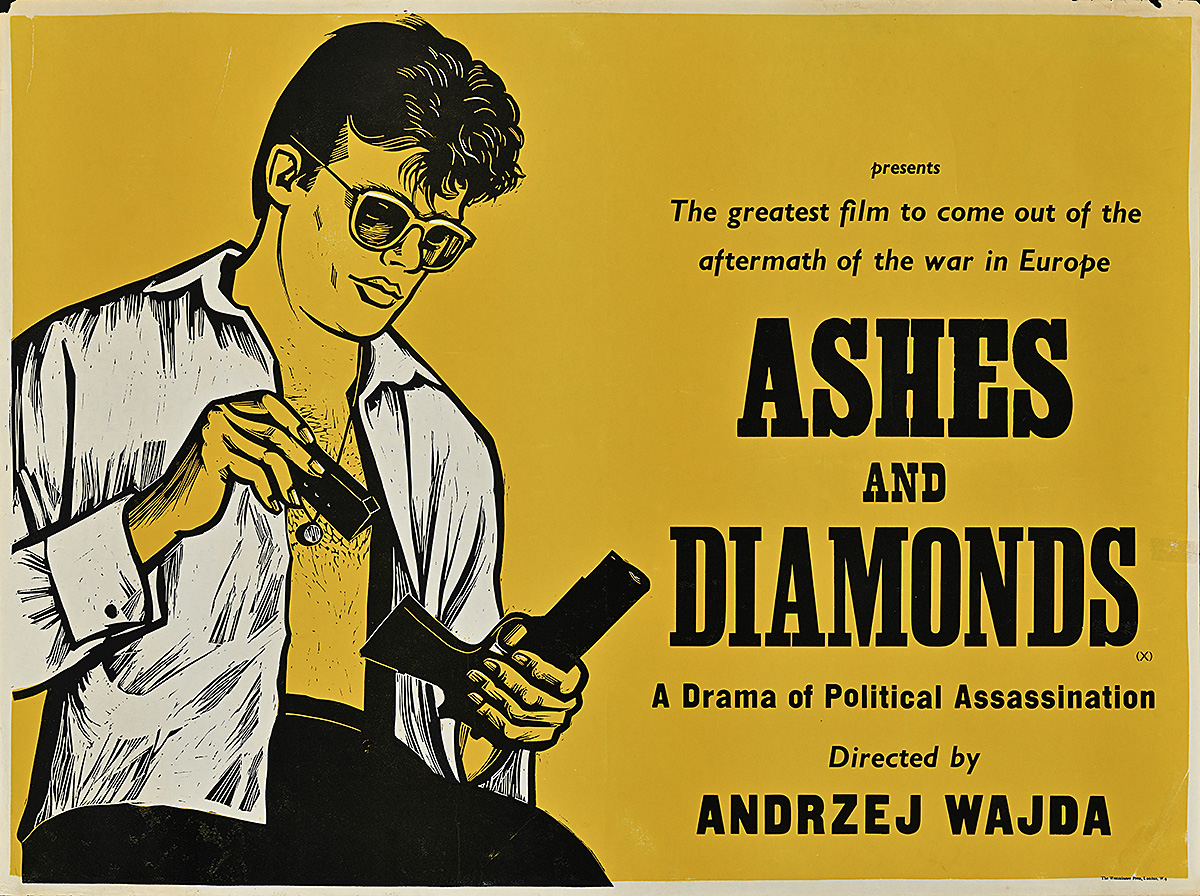

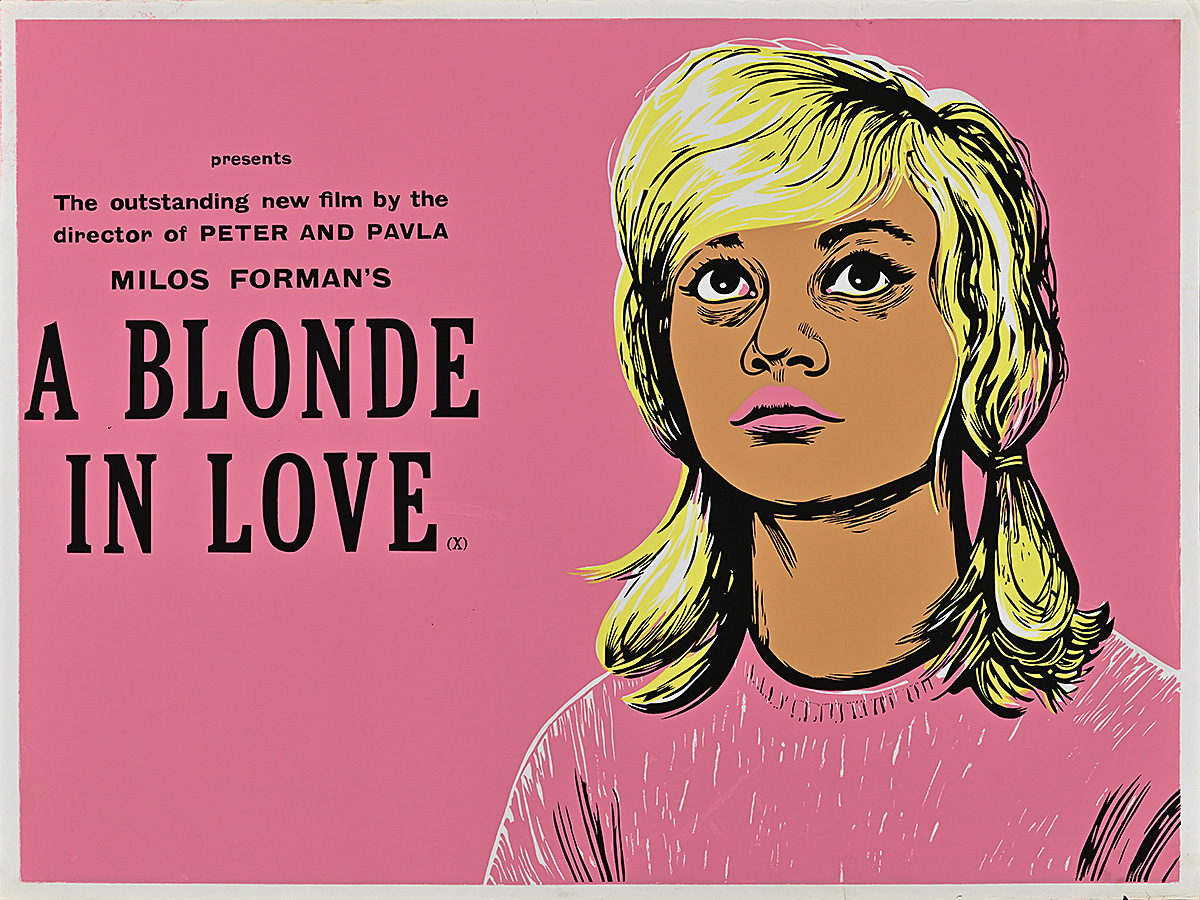

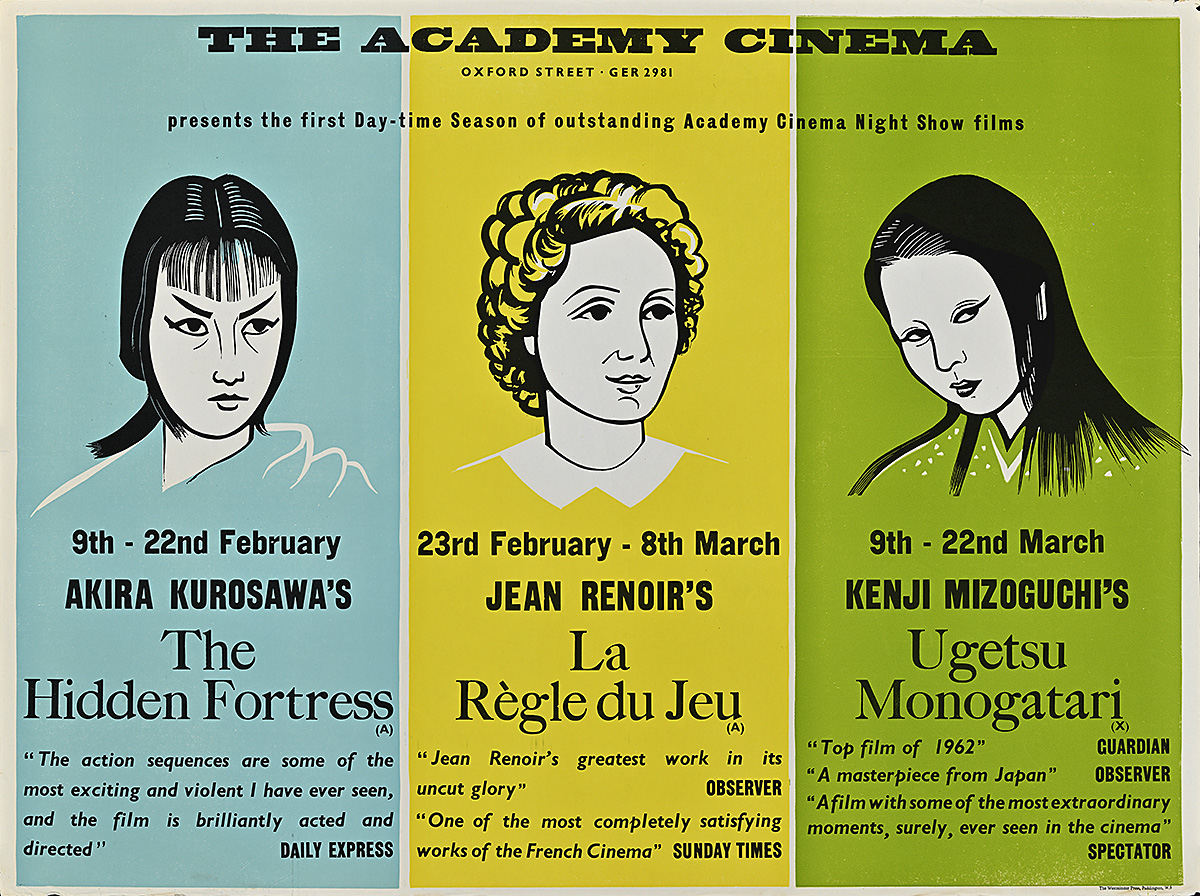

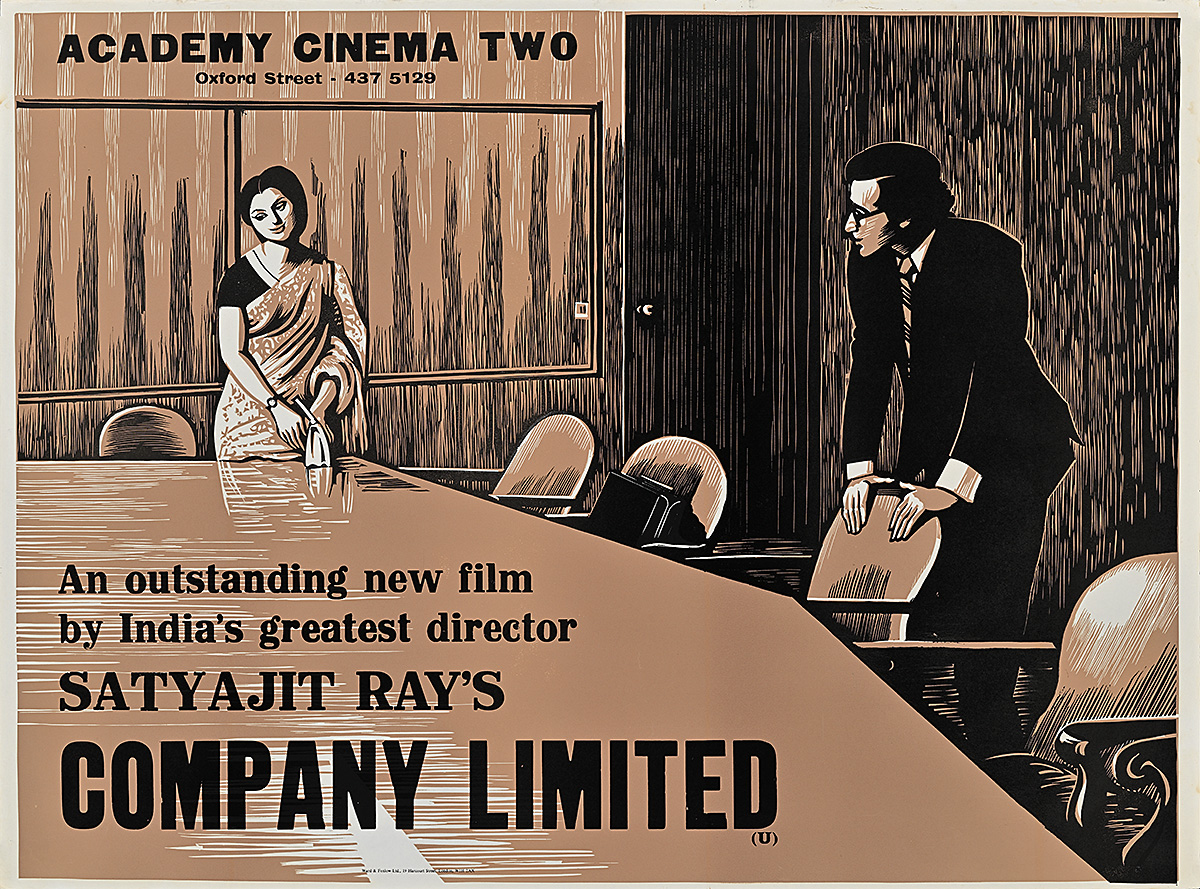

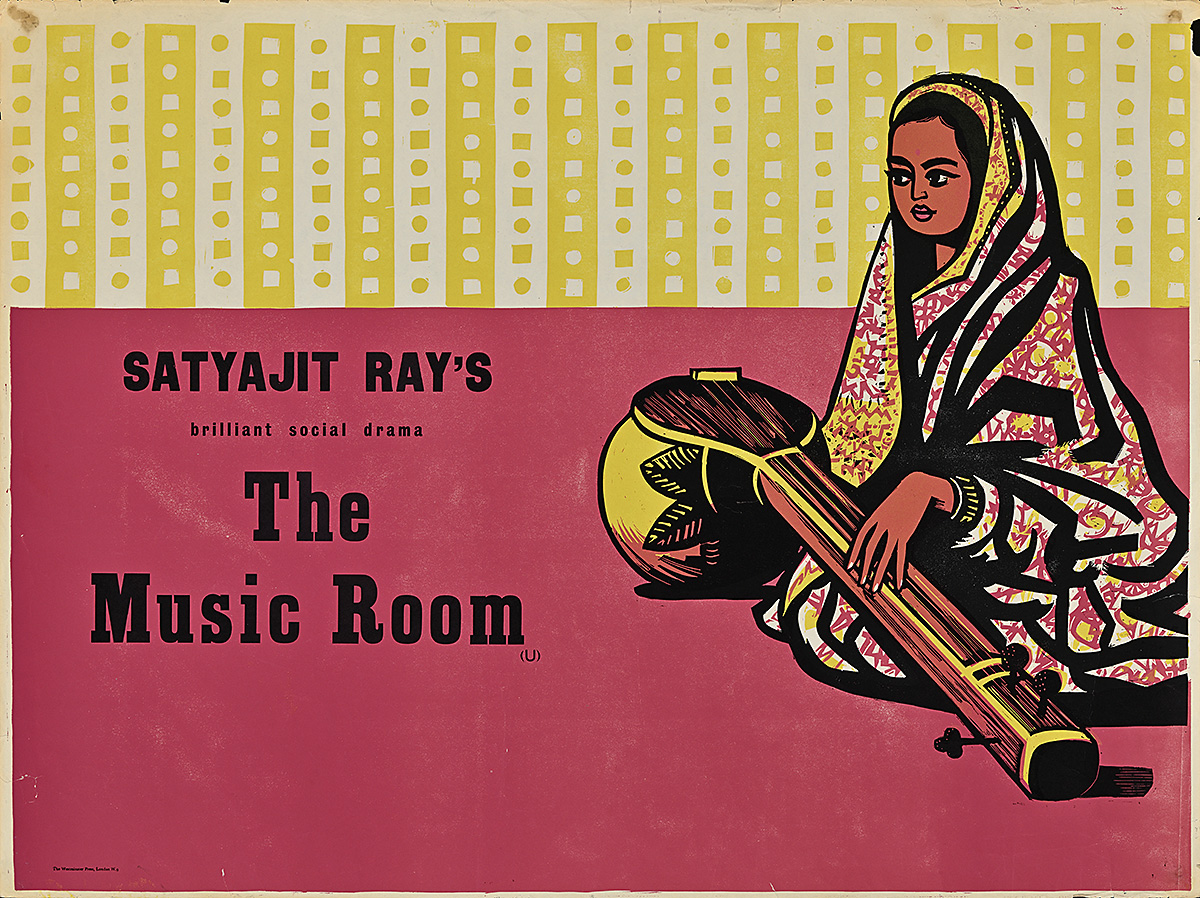

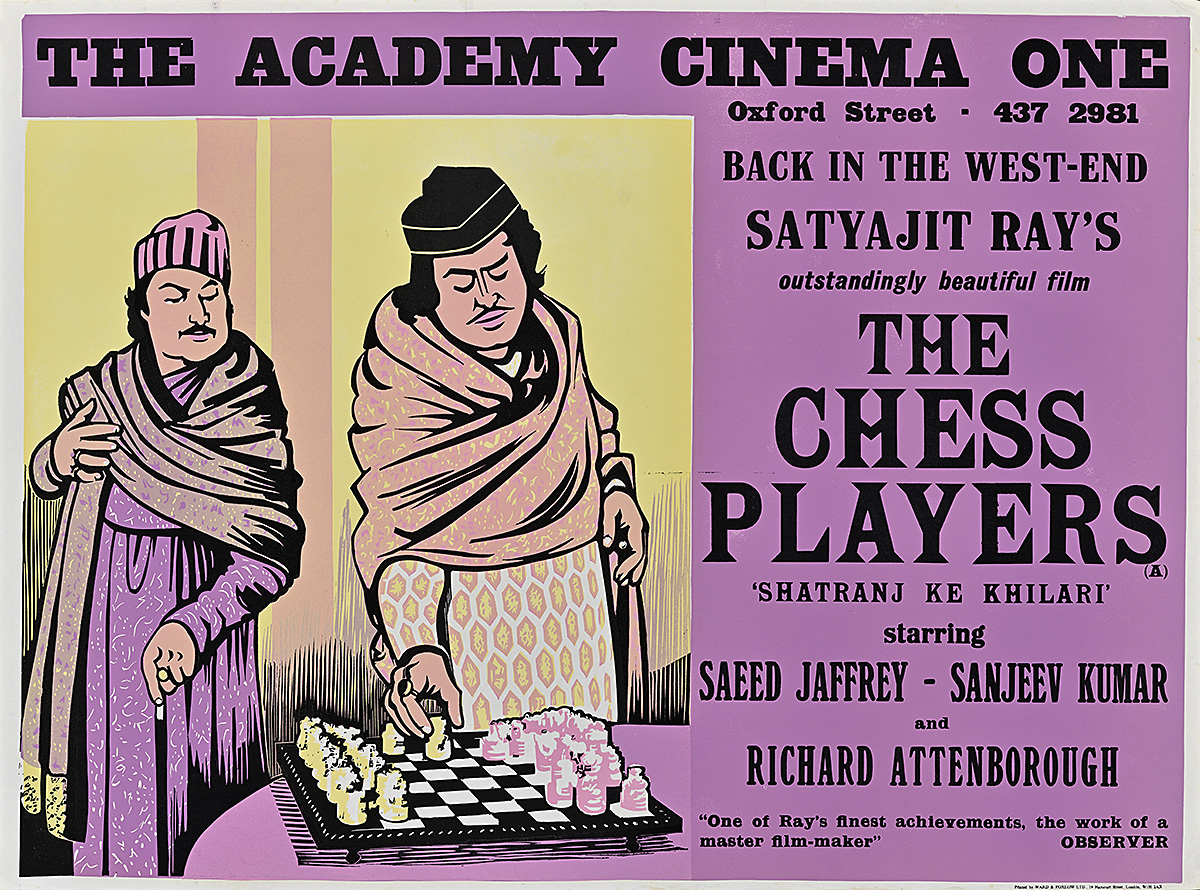

In operation from 1931 to 1986 (with a brief hiatus between 1940 and 1944 due to damage sustained during World War II), the Academy Cinema was London’s premier art house movie theater. Managed by Elsie Cohen, it specialized in international films that eschewed classic cause-and-effect narratives and instead highlighted a given director’s vision. This approach to moviemaking led many art house films of the period to be known primarily by the names of their directors rather than by those of their stars; Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa, François Truffaut, Ingmar Bergman, Andrzej Wajda, and Satyajit Ray still hold cult status for cinema aficionados. The output of such directors was often prolific since they did not have to navigate standard Hollywood bureaucracy and could therefore focus entirely on their craft. Of course, once these films achieved international fame, the larger movie industry began copying many of their visual techniques and storytelling methods; however, during the early to mid-20th century, art house remained a novel and daring form of cinema showcased by only a few theaters.

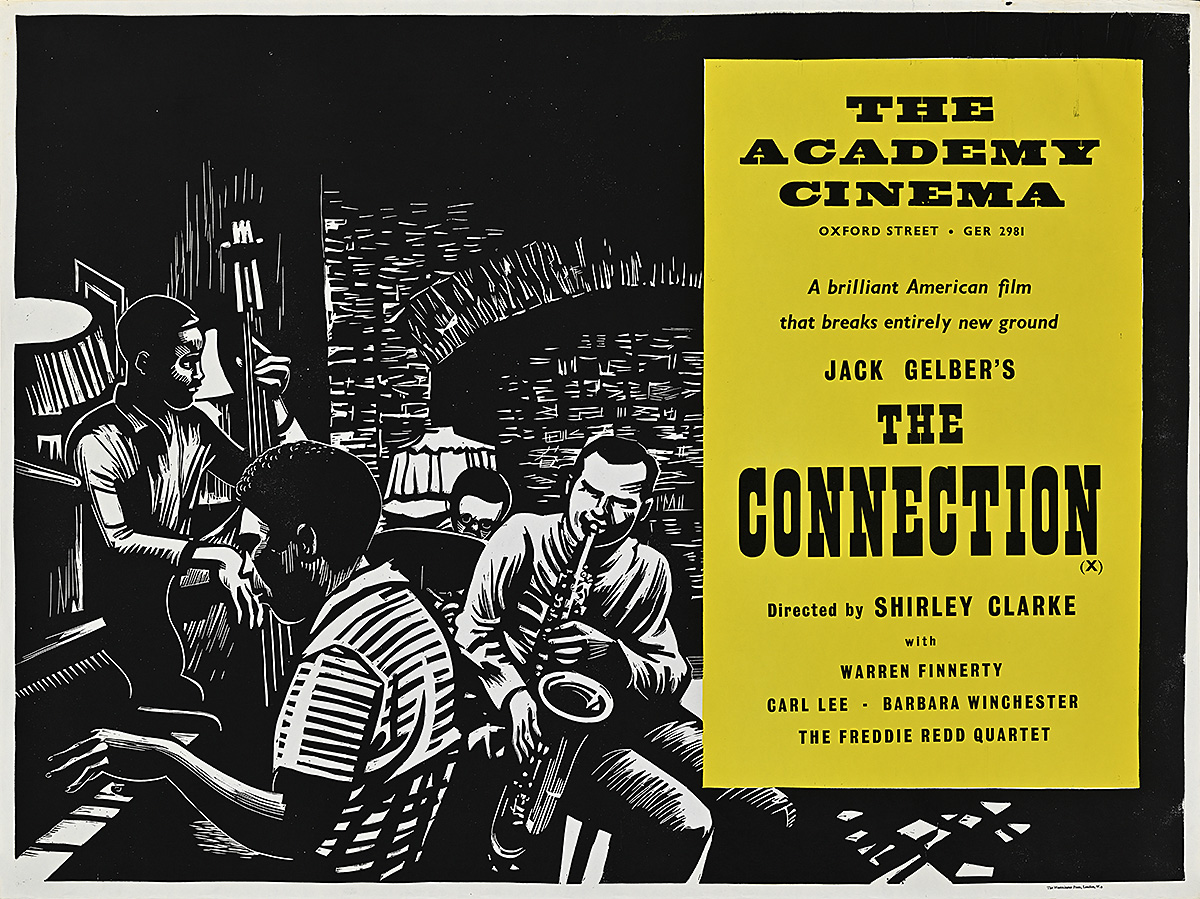

Elsie Cohen believed strongly in the purpose of her theater and in 1937 she hired George Hoellering, an Austrian-Jewish refugee, film producer, and director, as the Academy’s deputy general manager. When Great Britain entered World War II in September 1939, however, any residents born in countries with which England was now at war were classified as “enemy aliens,” and many were sent to internment camps around the country. Hoellering was imprisoned in Onchan Camp on the Isle of Man, one of the larger facilities that became a residence to many foreign-born artists and academics. While there, he formed a deep friendship with Peter Strausfeld, a German refugee and artist whom he ultimately hired to create the Academy’s unique advertising posters from 1945 until Strausfeld’s death in 1980.

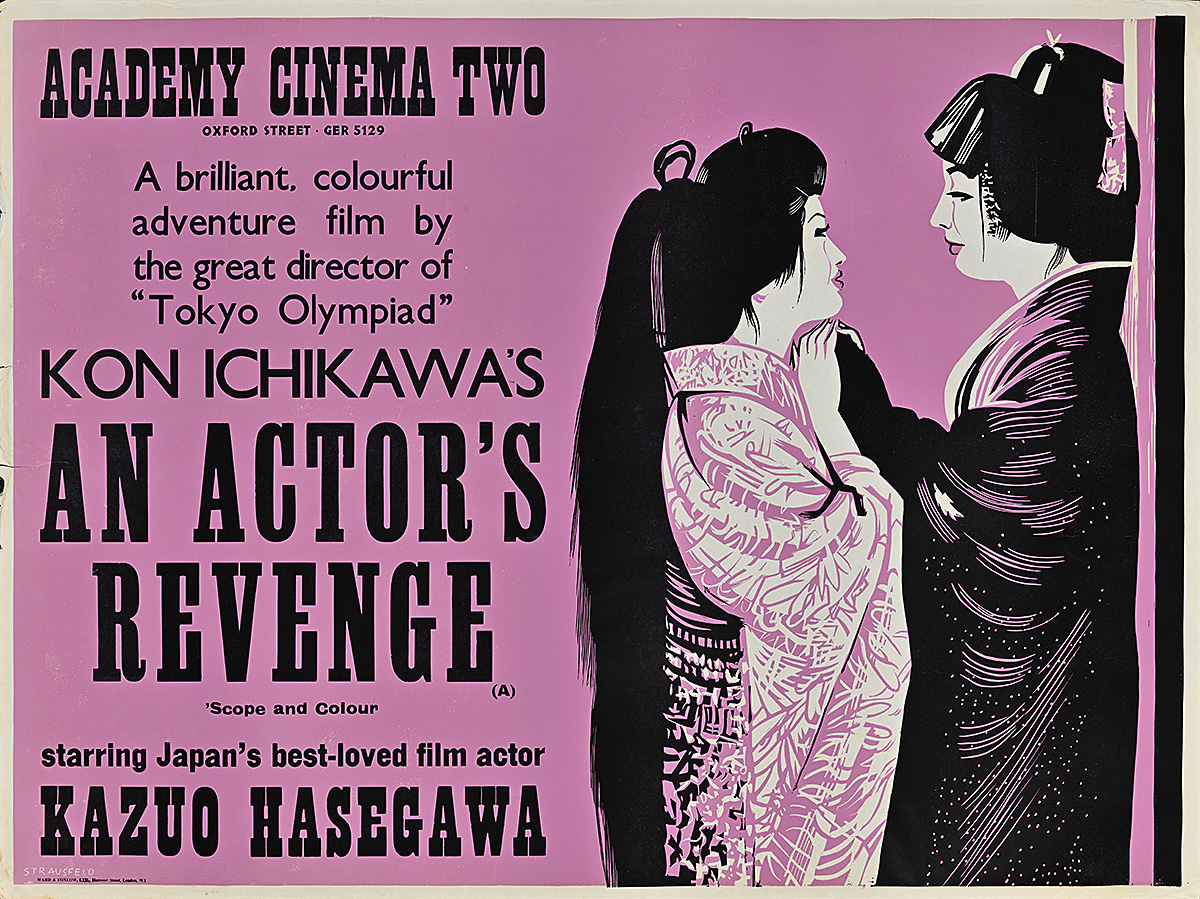

Both Strausfeld and Hoellering had lived in Berlin during the 1930s and would have been familiar with the lithographic posters created by Josef Fenneker for the Marmorhaus cinema. Never before had a theater commissioned its own unique posters for films, and Fenneker’s designs stood out dramatically for their unique approach to advertising. In this same manner, Strausfeld created more than three hundred bold, predominantly single-color linocut compositions with a deceptively simple hand-printed feel. Where mainstream movie posters typically relied on colorful, montage-style interpretations of scenes from a film combined with striking typography, Strausfeld’s posters were the opposite. Originally printed on bookbinders’ linen because of the wartime paper shortage, they were first posted at bomb sites around the city. Once paper was more readily available, editions of 100 to 350 copies began appearing in London’s subway system, expanding through design the audience for what was a relatively niche product. These posters remain some of the most unique examples of localized cinema advertising in movie history.

Unless otherwise noted, all posters are from the collection of Michael Lellouche.

Whenever feasible, Poster House reuses materials from previous shows to drive sustainable practice.

Large text, Spanish translation, and a Plain Language summary are available via the QR code and at the Info Desk.

El texto con letra grande, la traducción al español y un resumen en lectura fácil están disponibles a través del código QR y en atención al público.

A catalogue of this exhibition is available in the Shop.