The Road to Disarmament

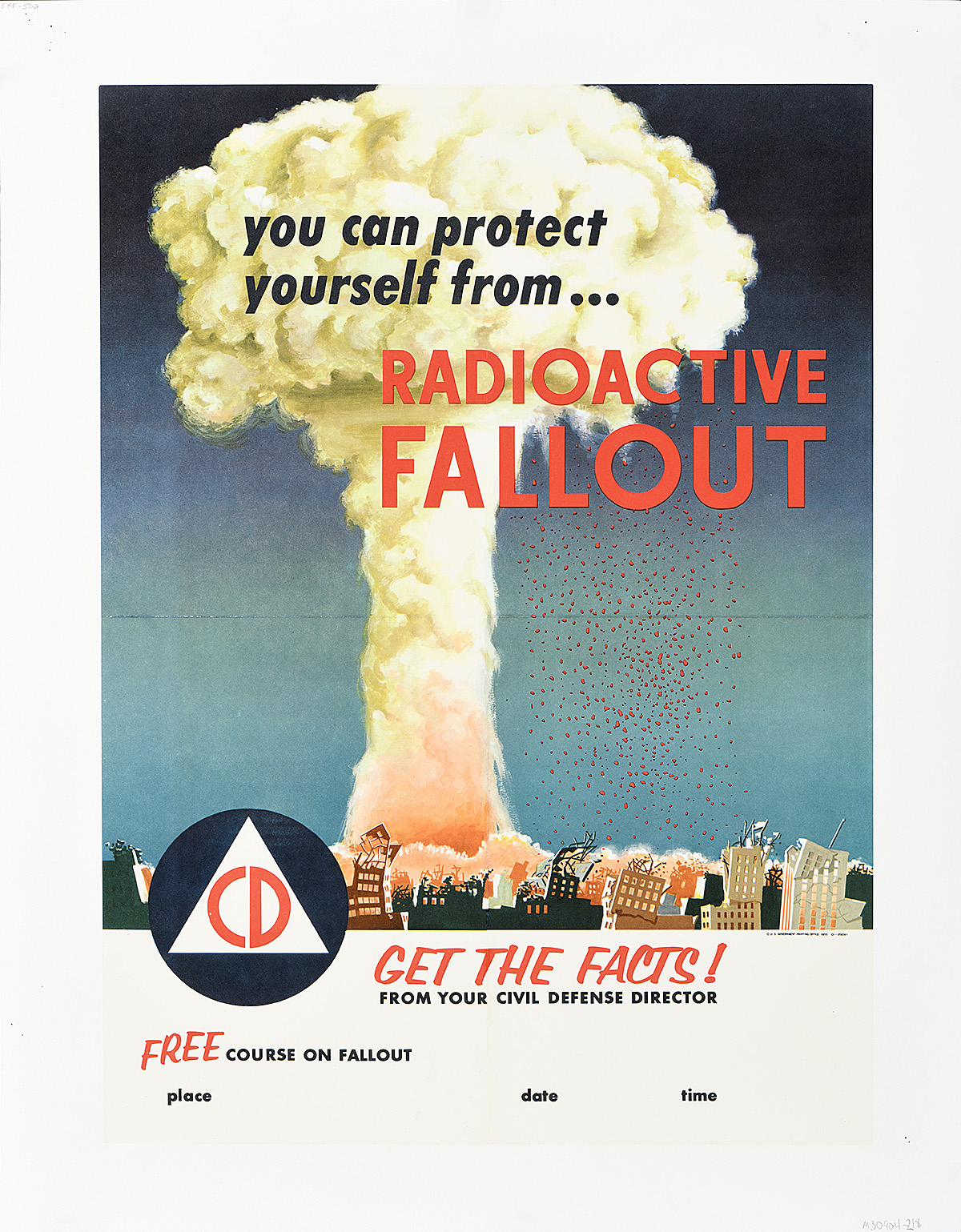

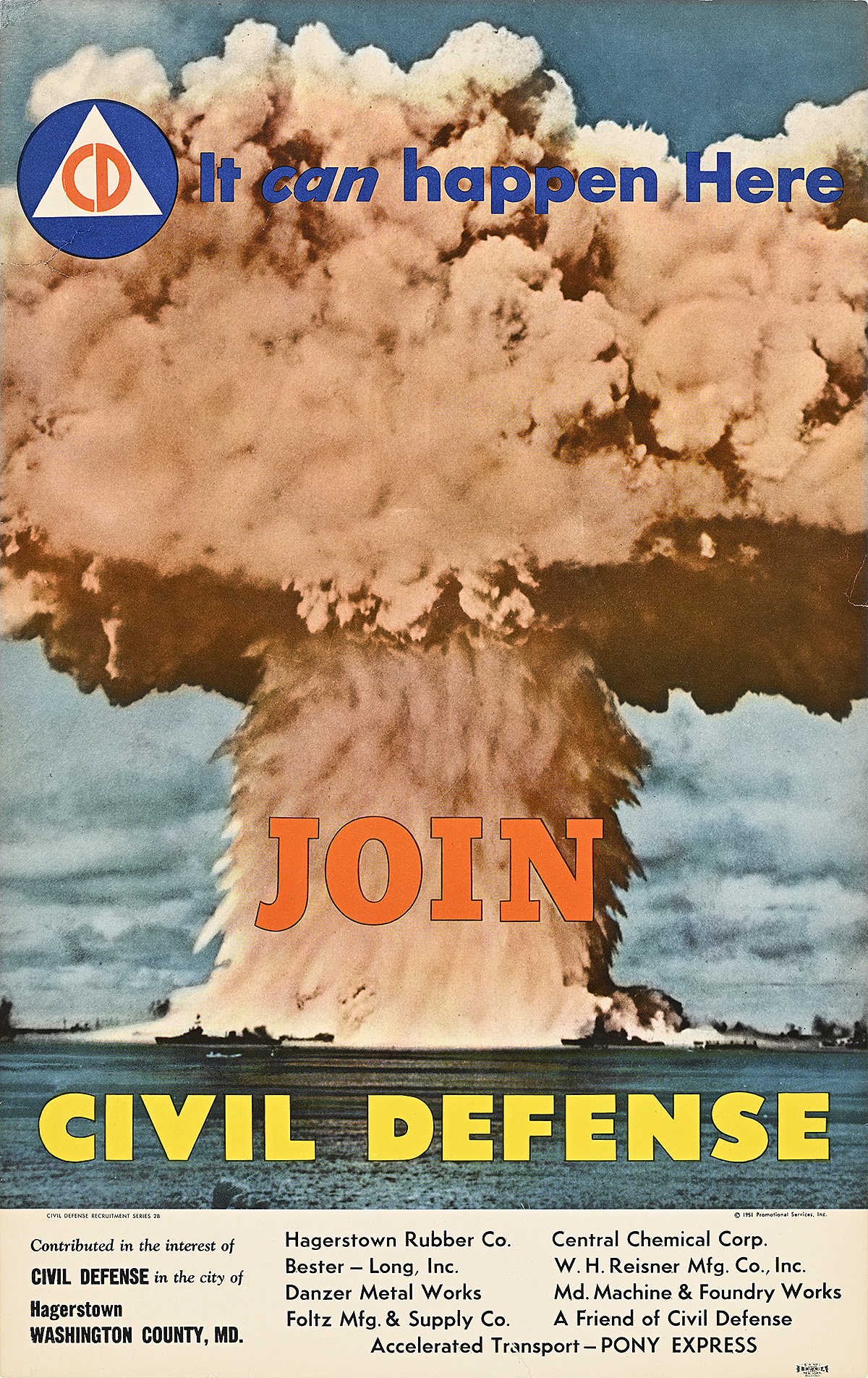

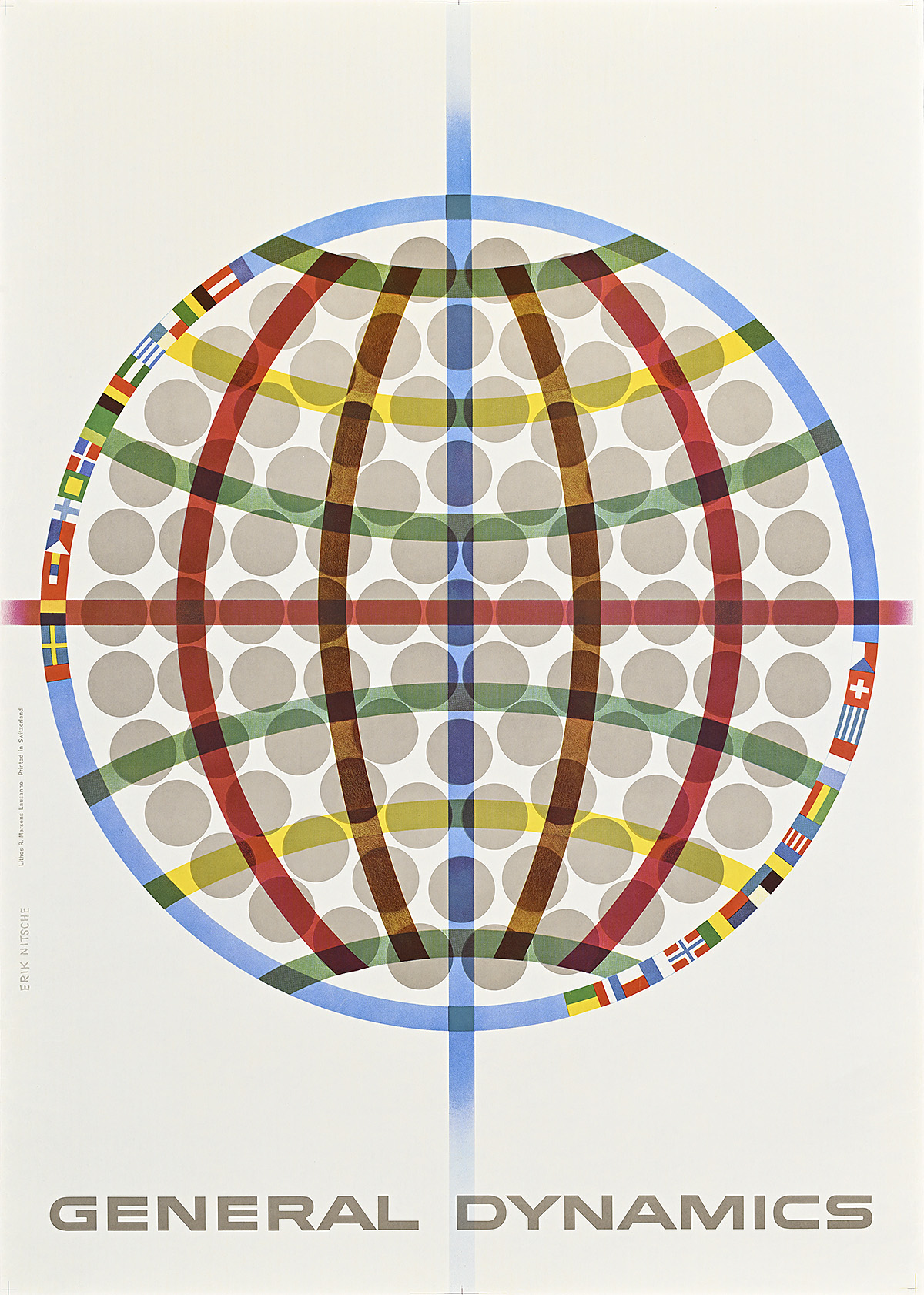

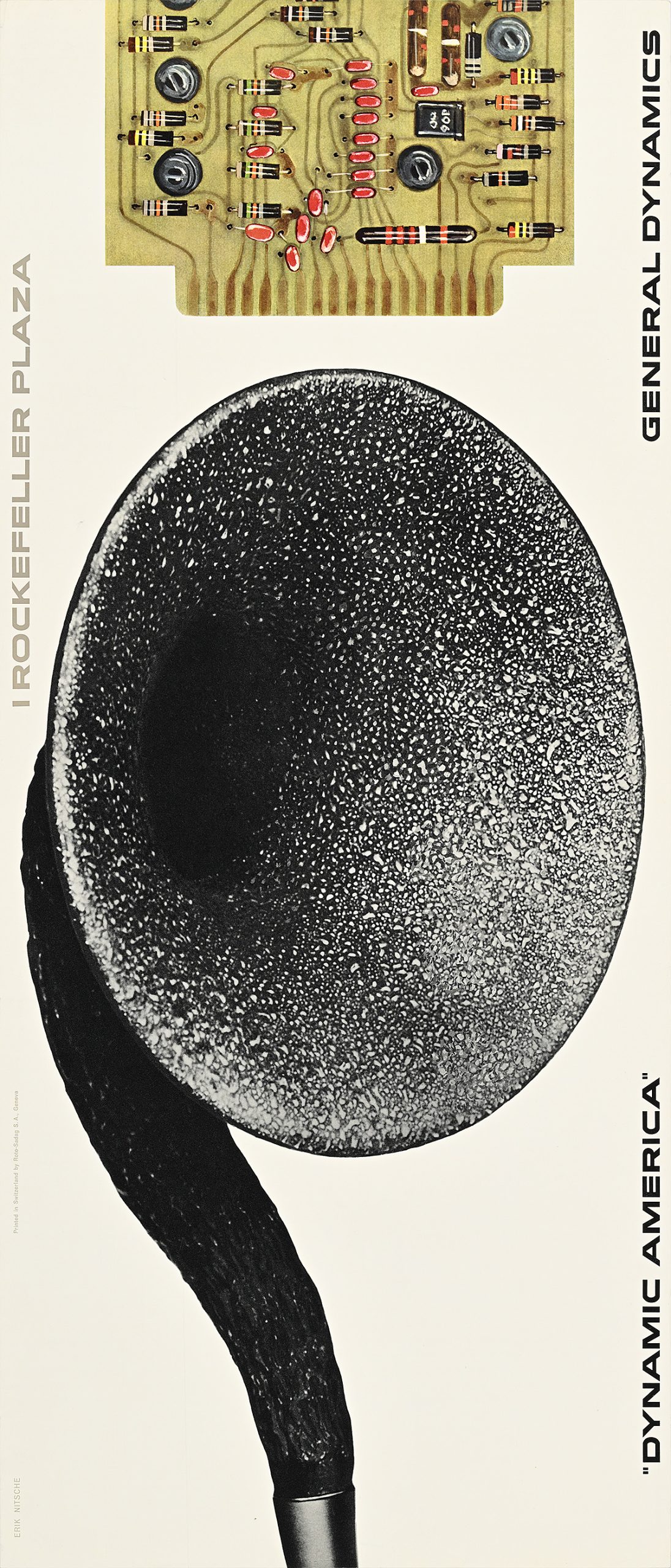

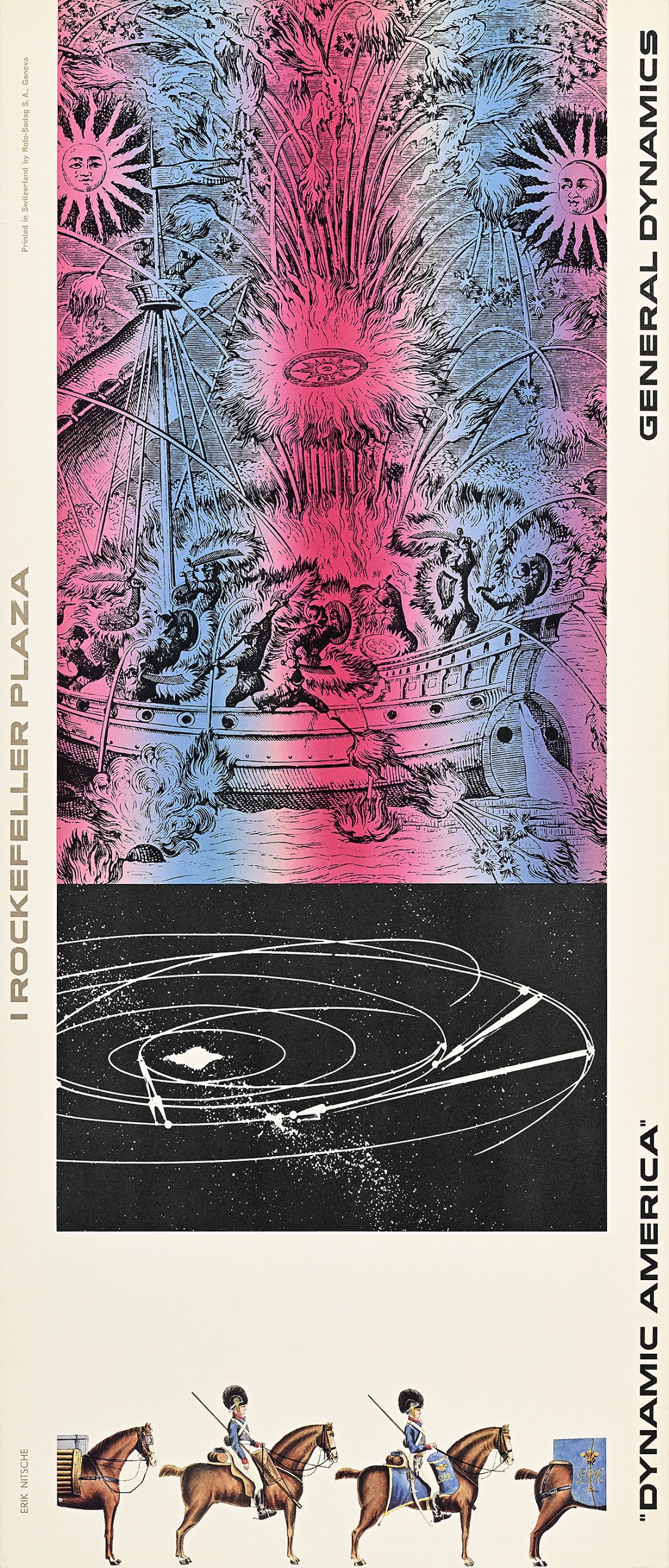

When Dwight D. Eisenhower became president in 1953, the United States had one thousand nuclear warheads. When he left office in 1961, it had twenty-three thousand. Military might had become big business—and Eisenhower warned about the consequences of this in his final address to the American public:

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machine of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together. Disarmament, with mutual honor and confidence is a continuing imperative. As one who has witnessed the horror and lingering sadness of war—as one who knows that another war could utterly destroy this civilization—I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.”

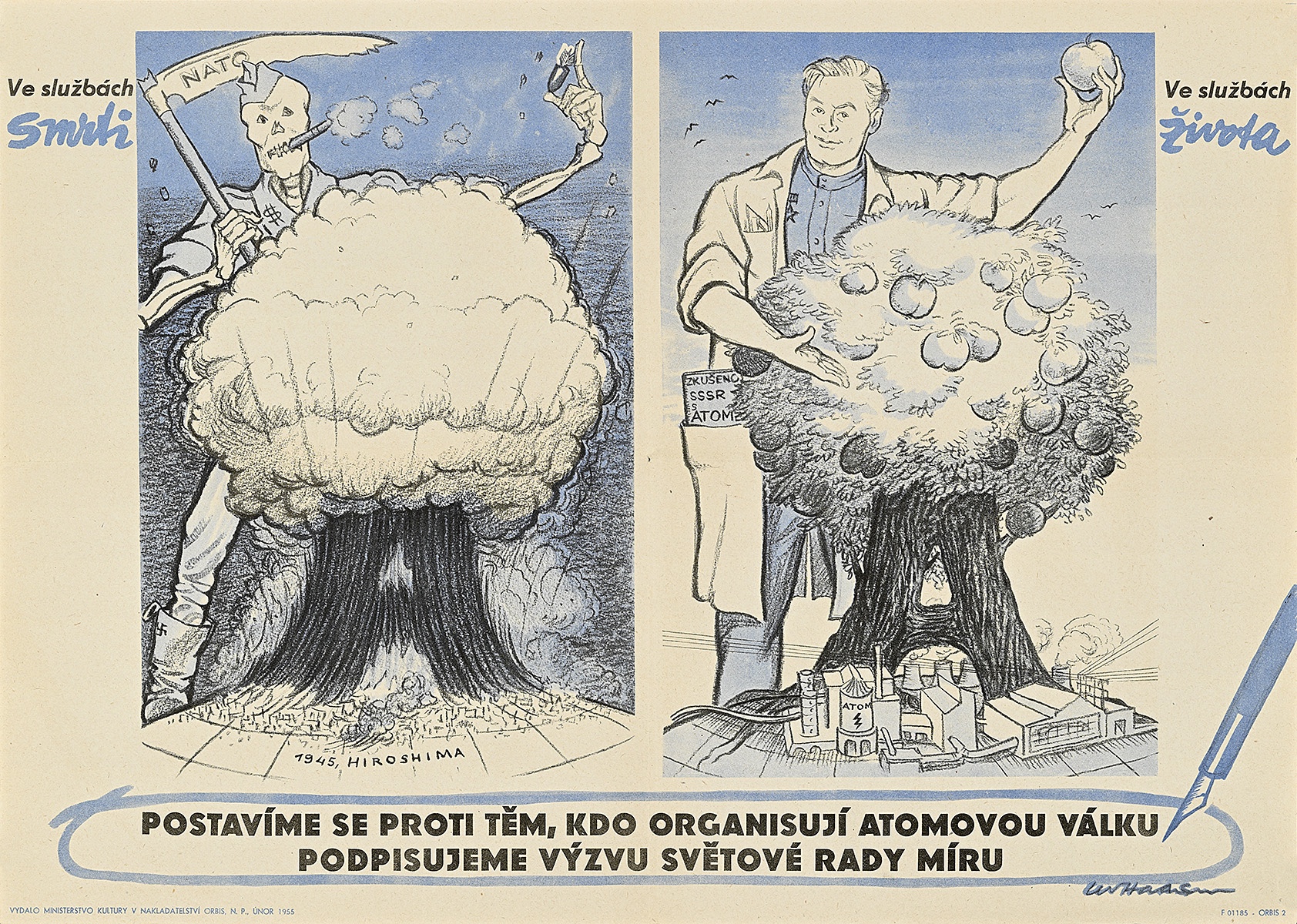

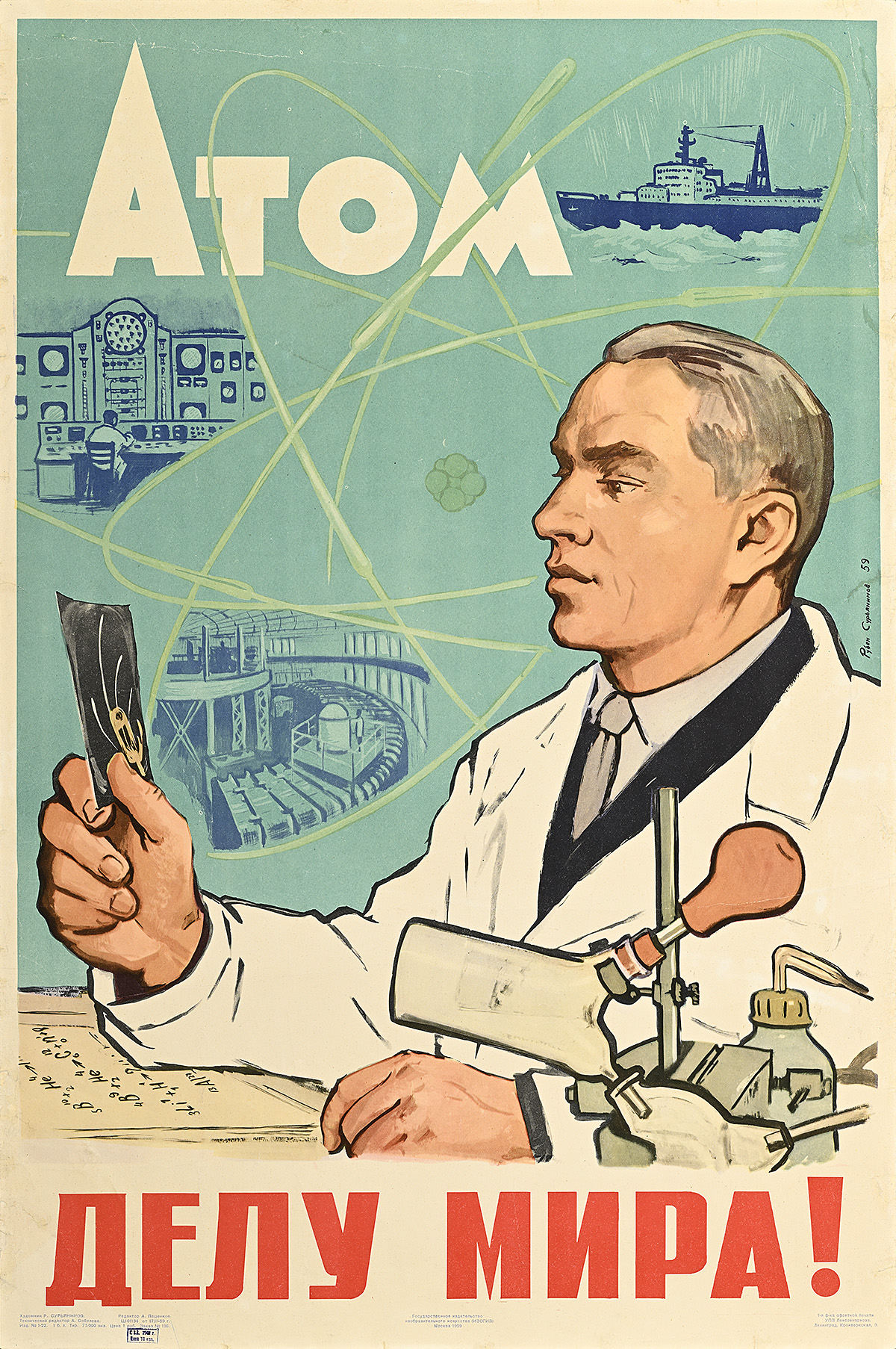

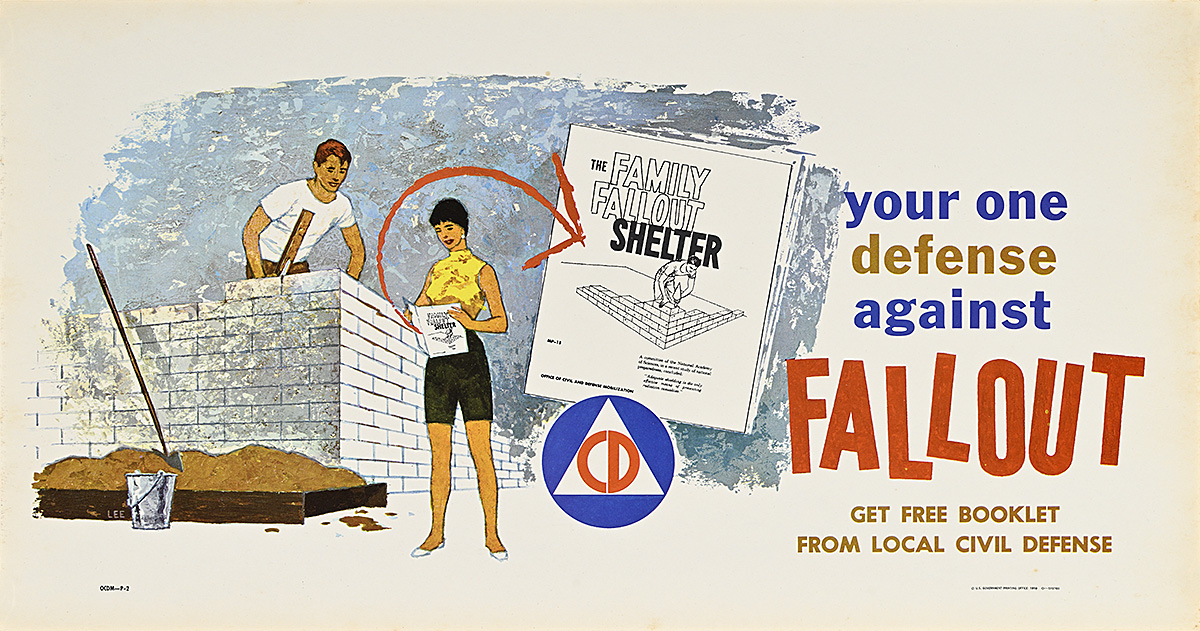

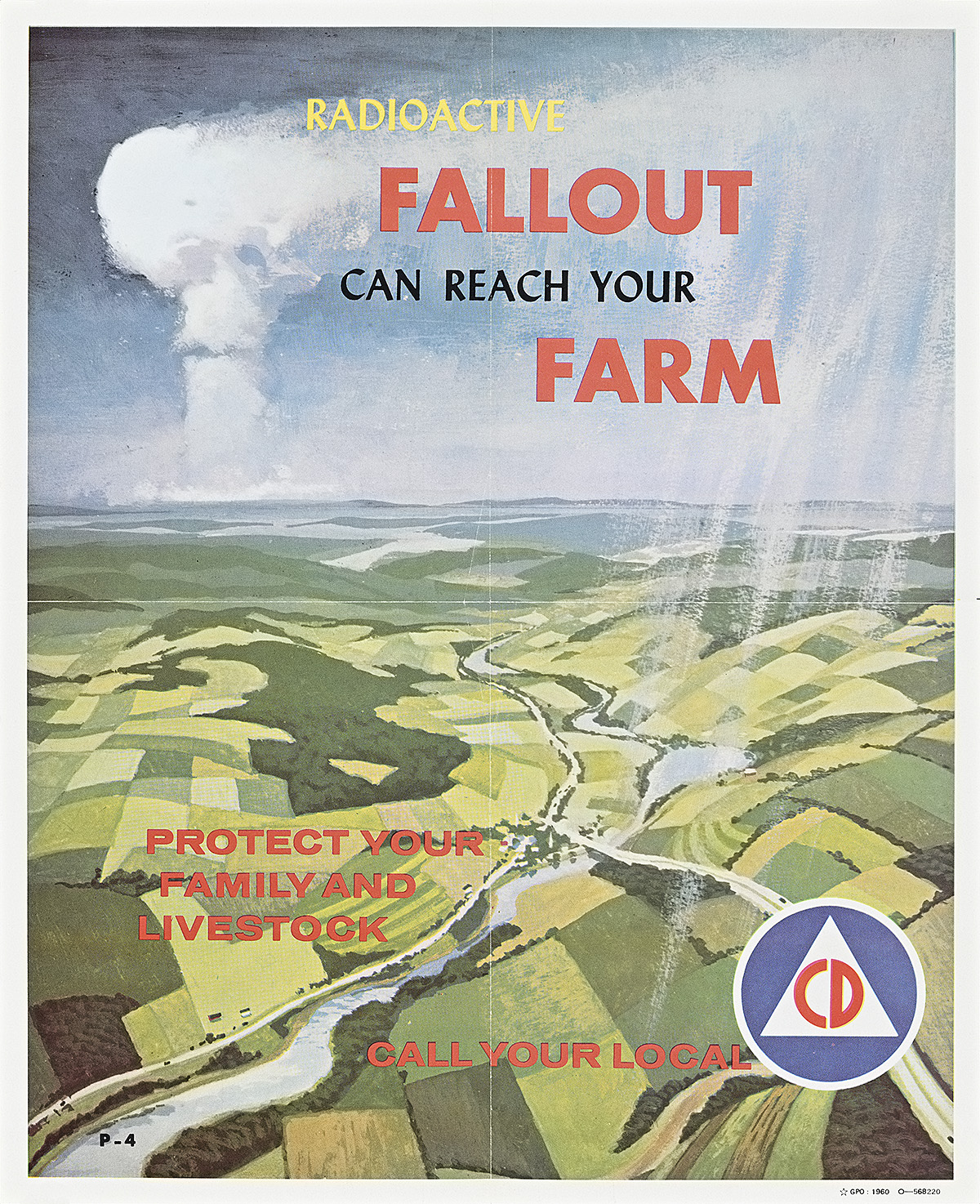

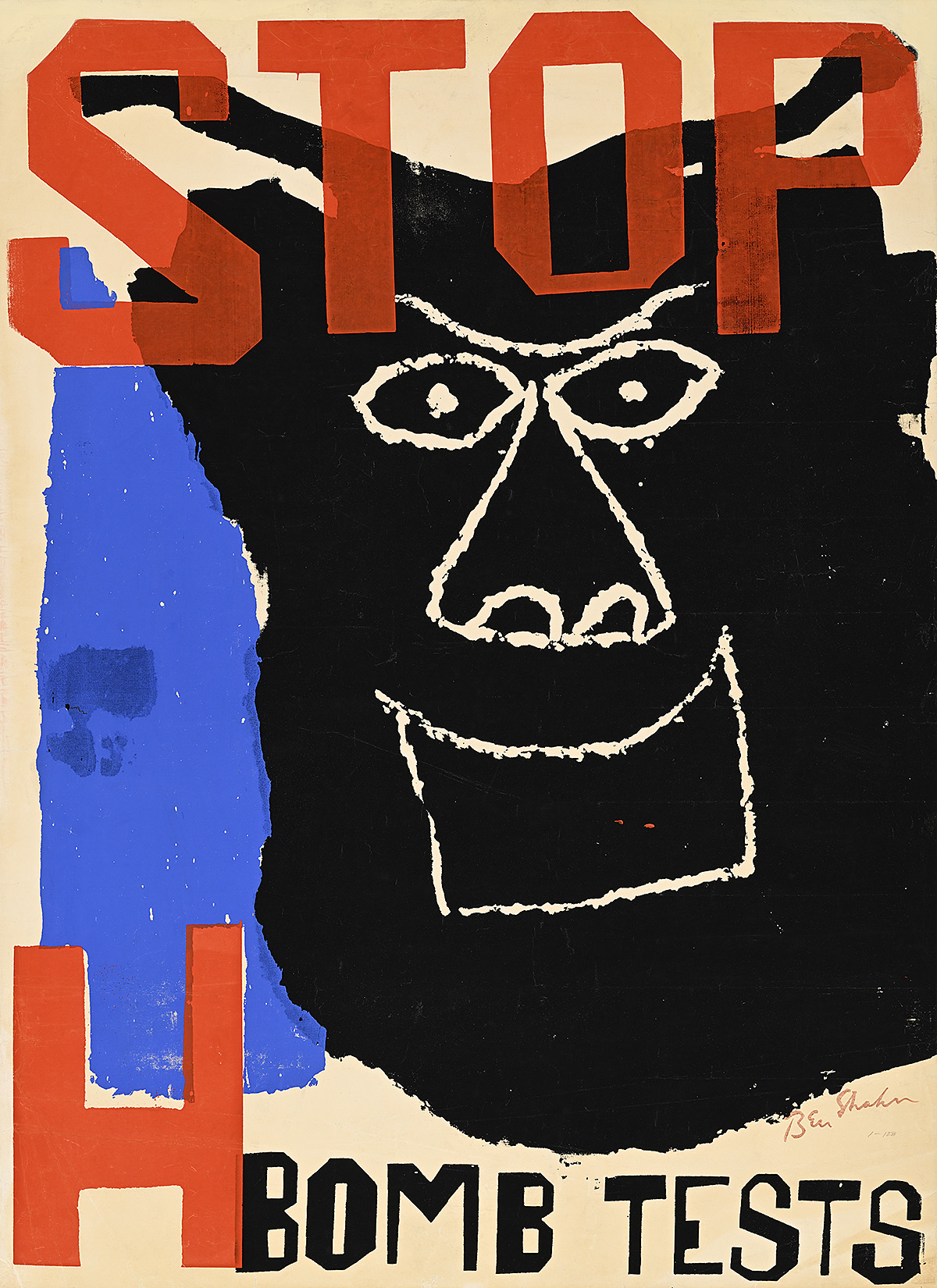

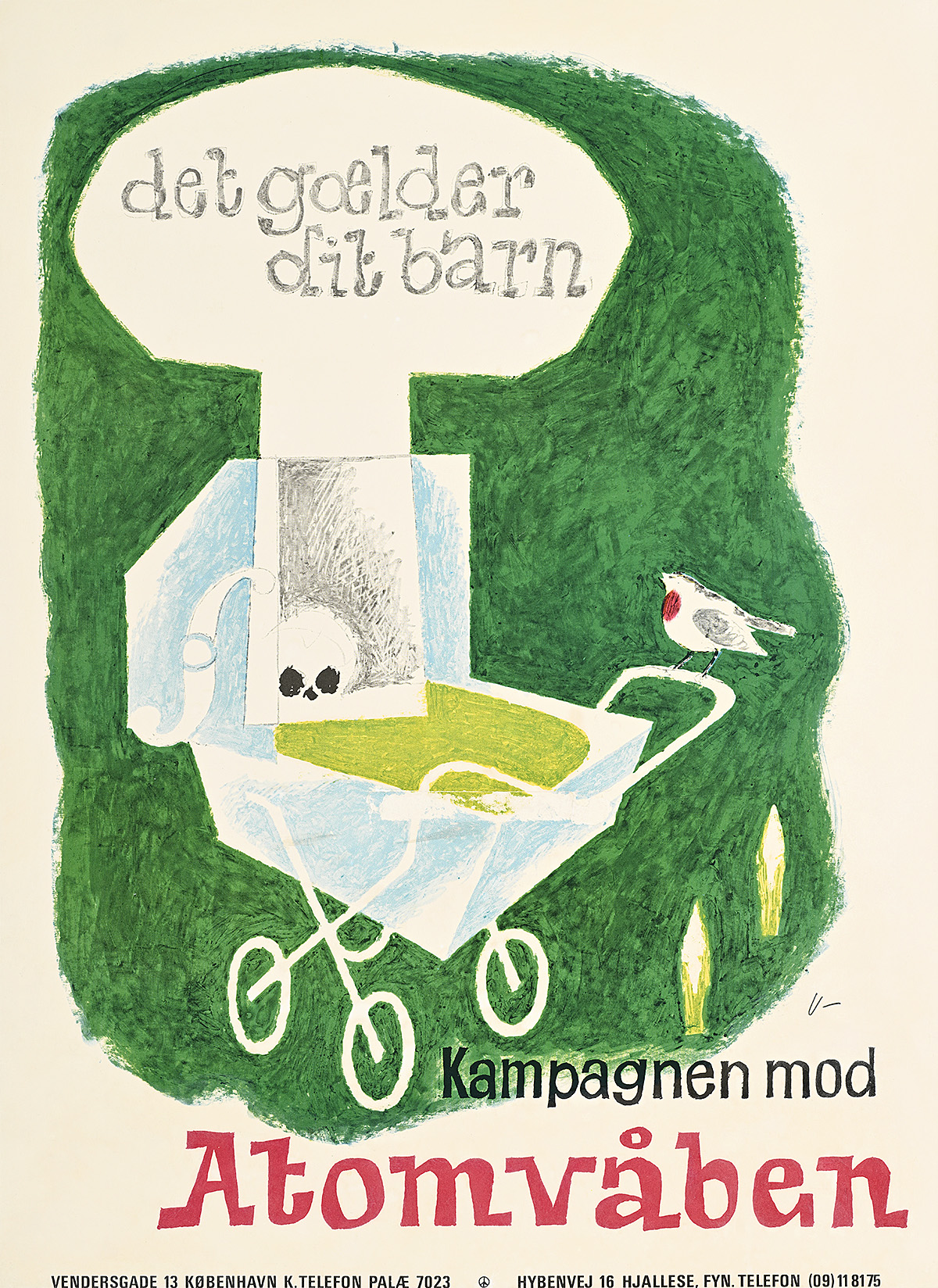

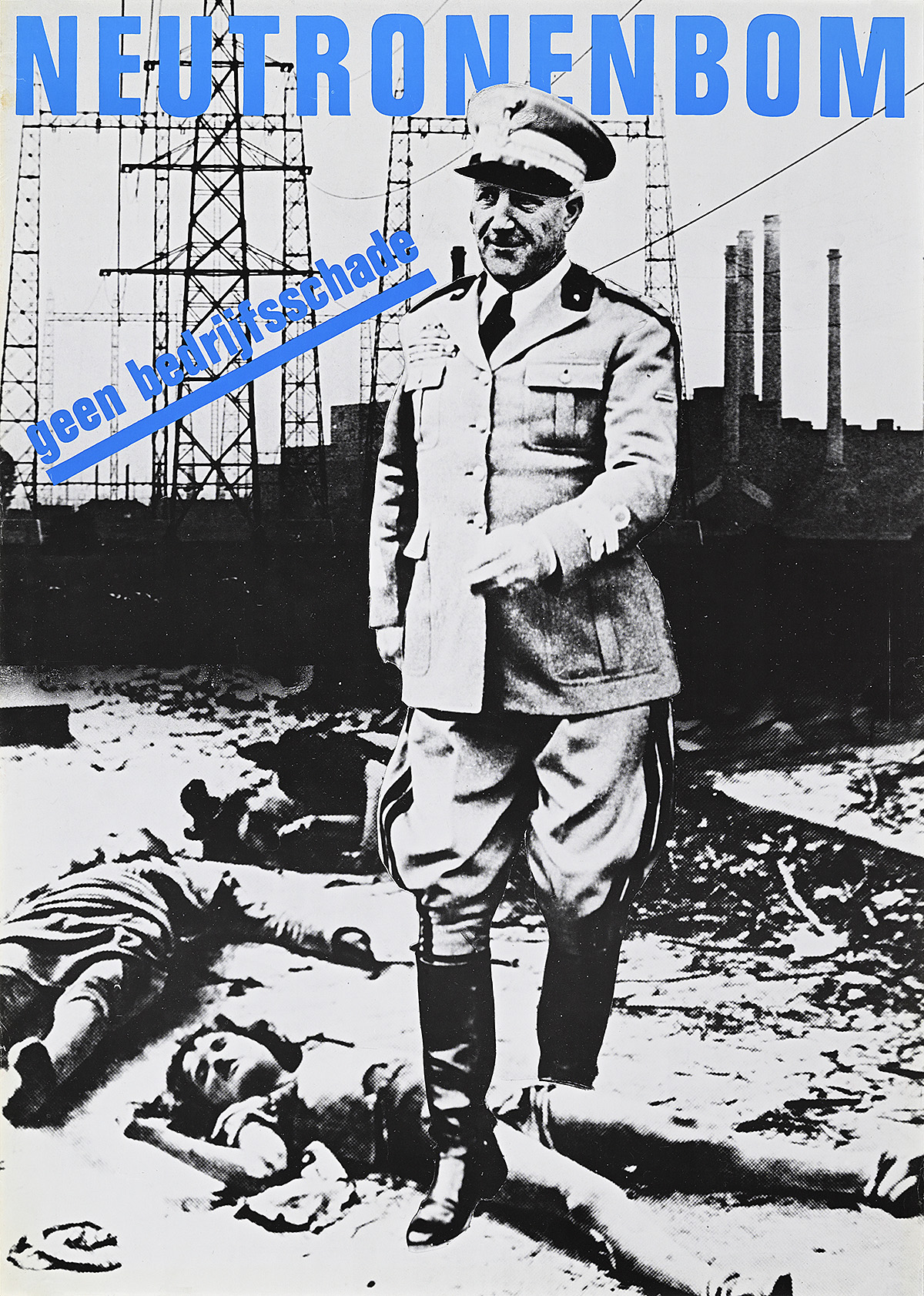

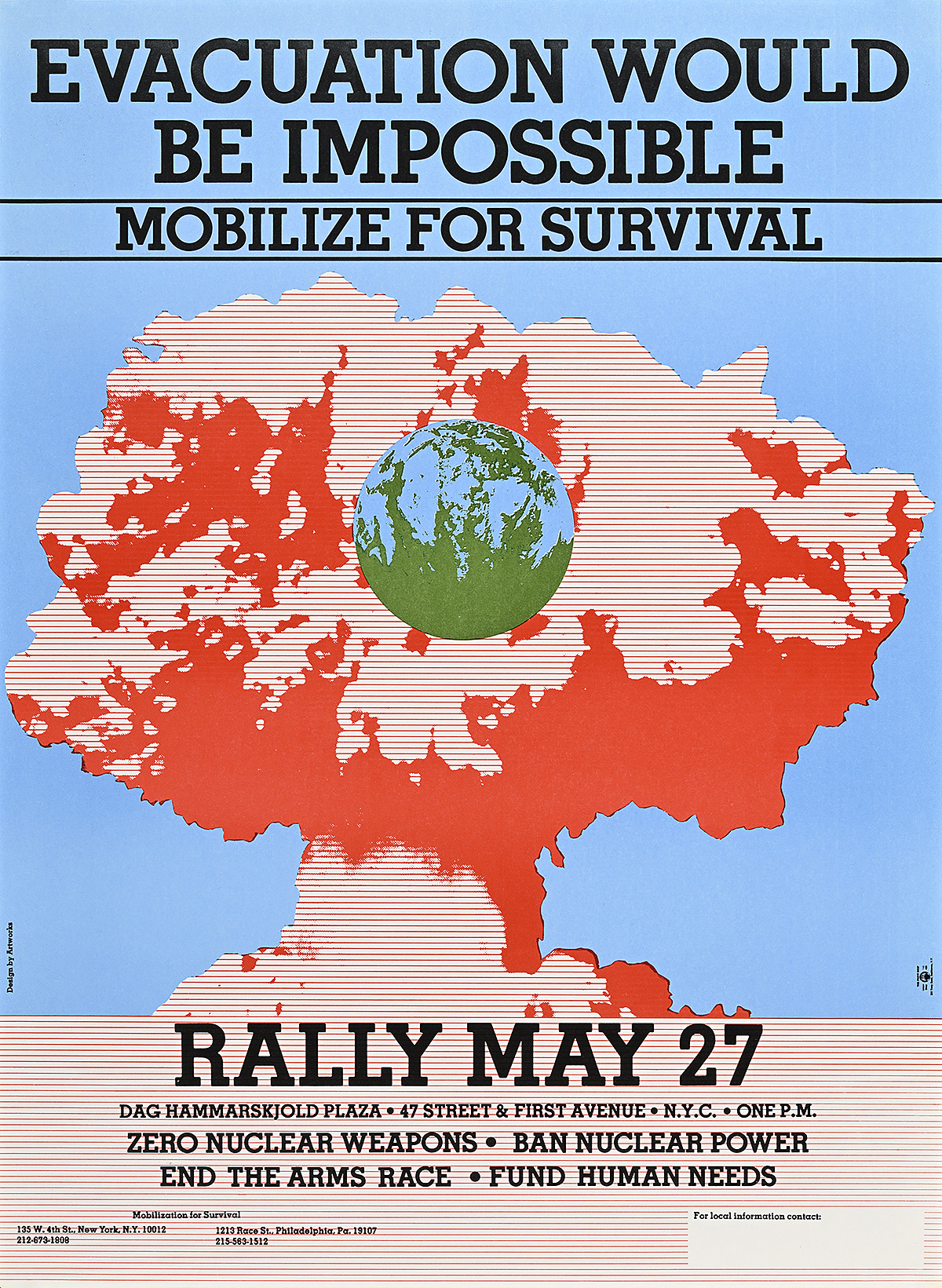

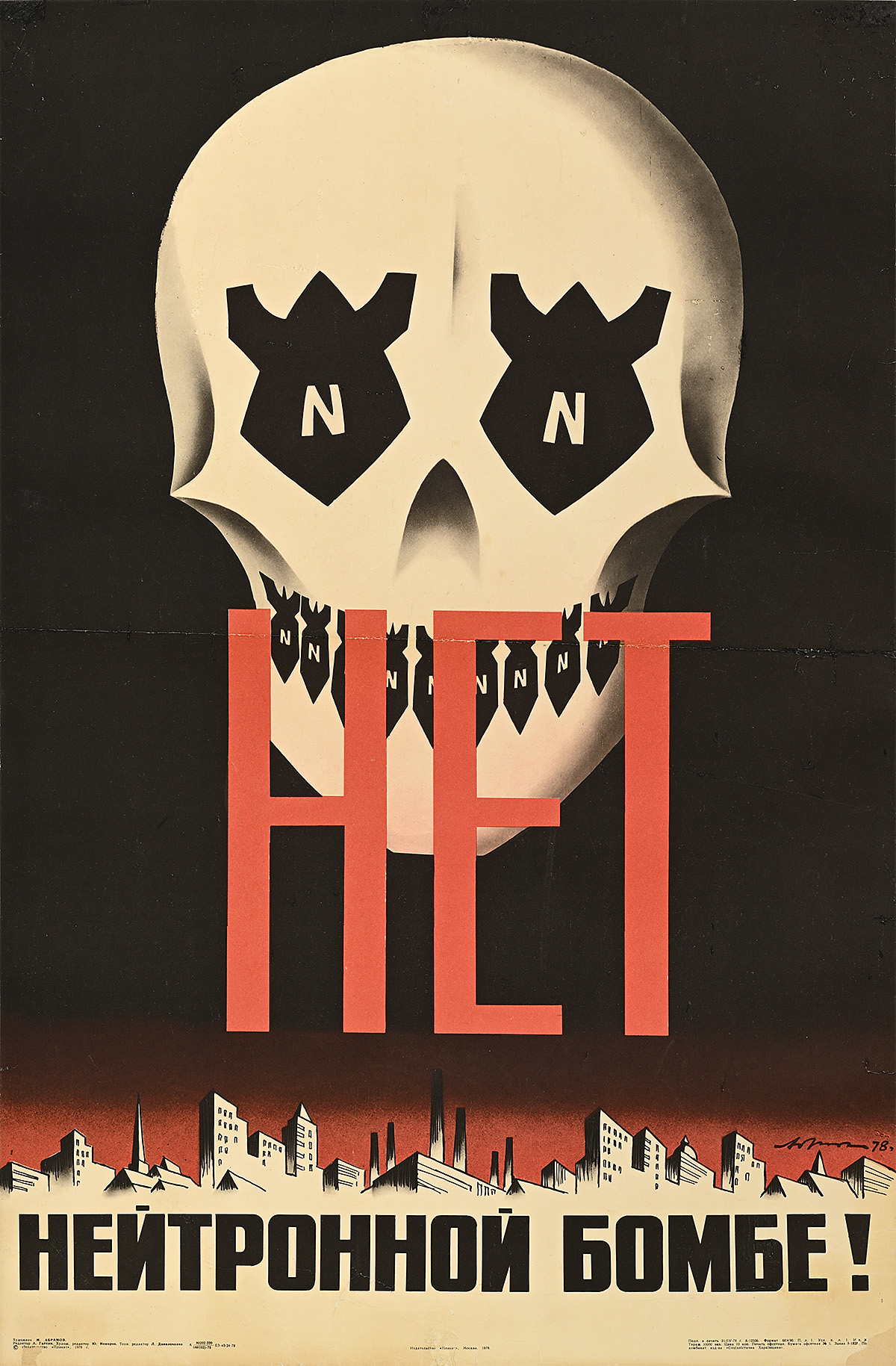

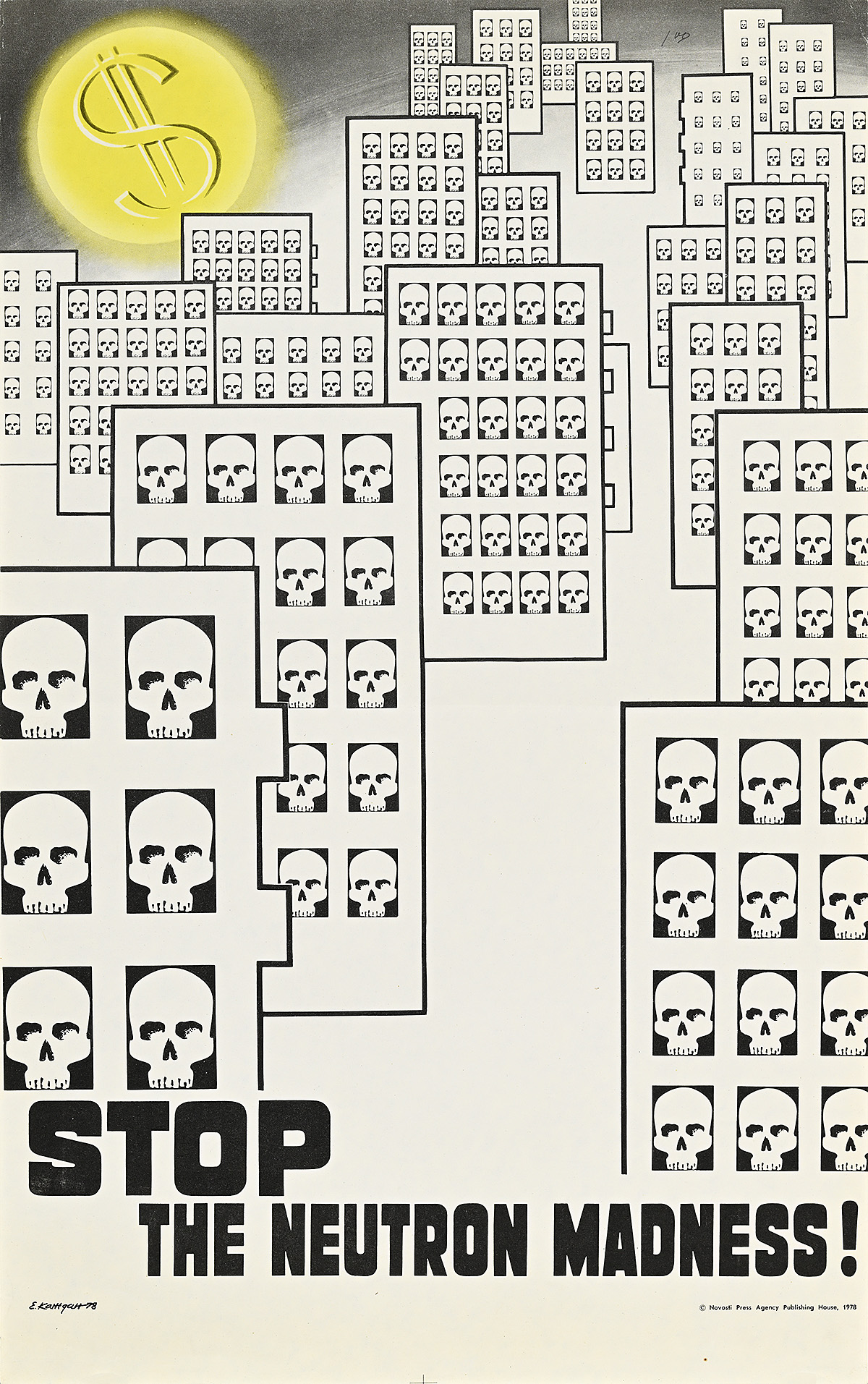

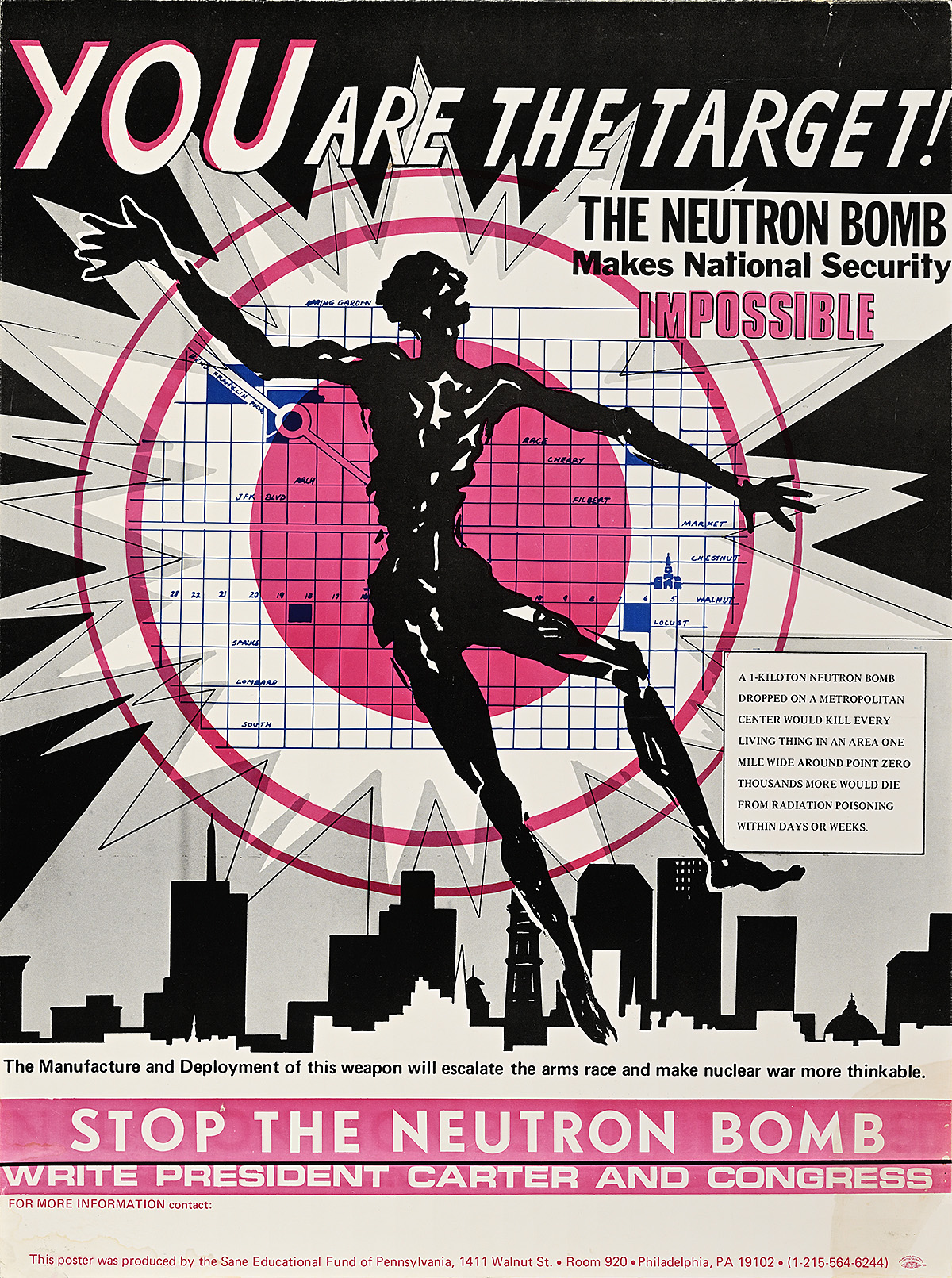

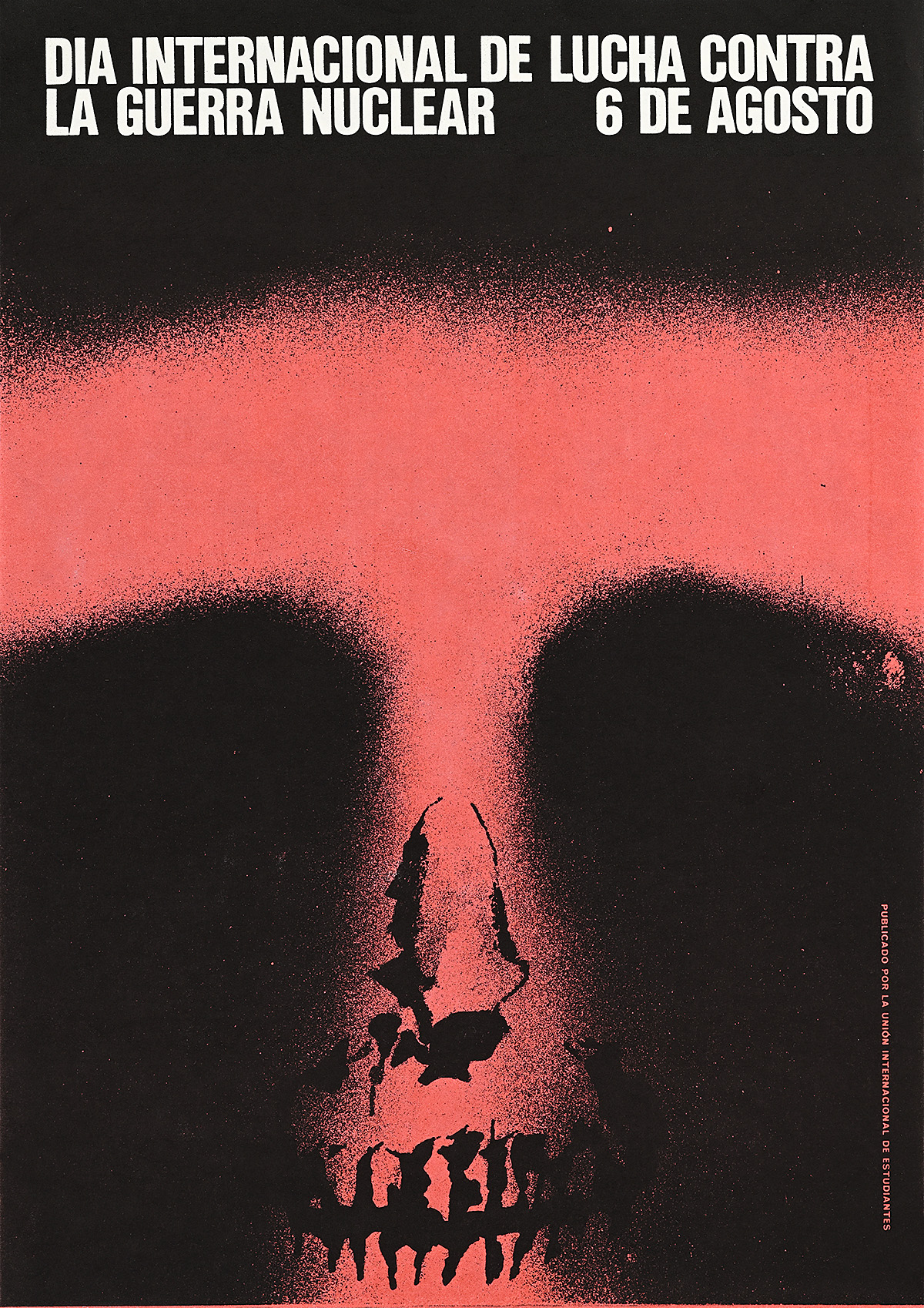

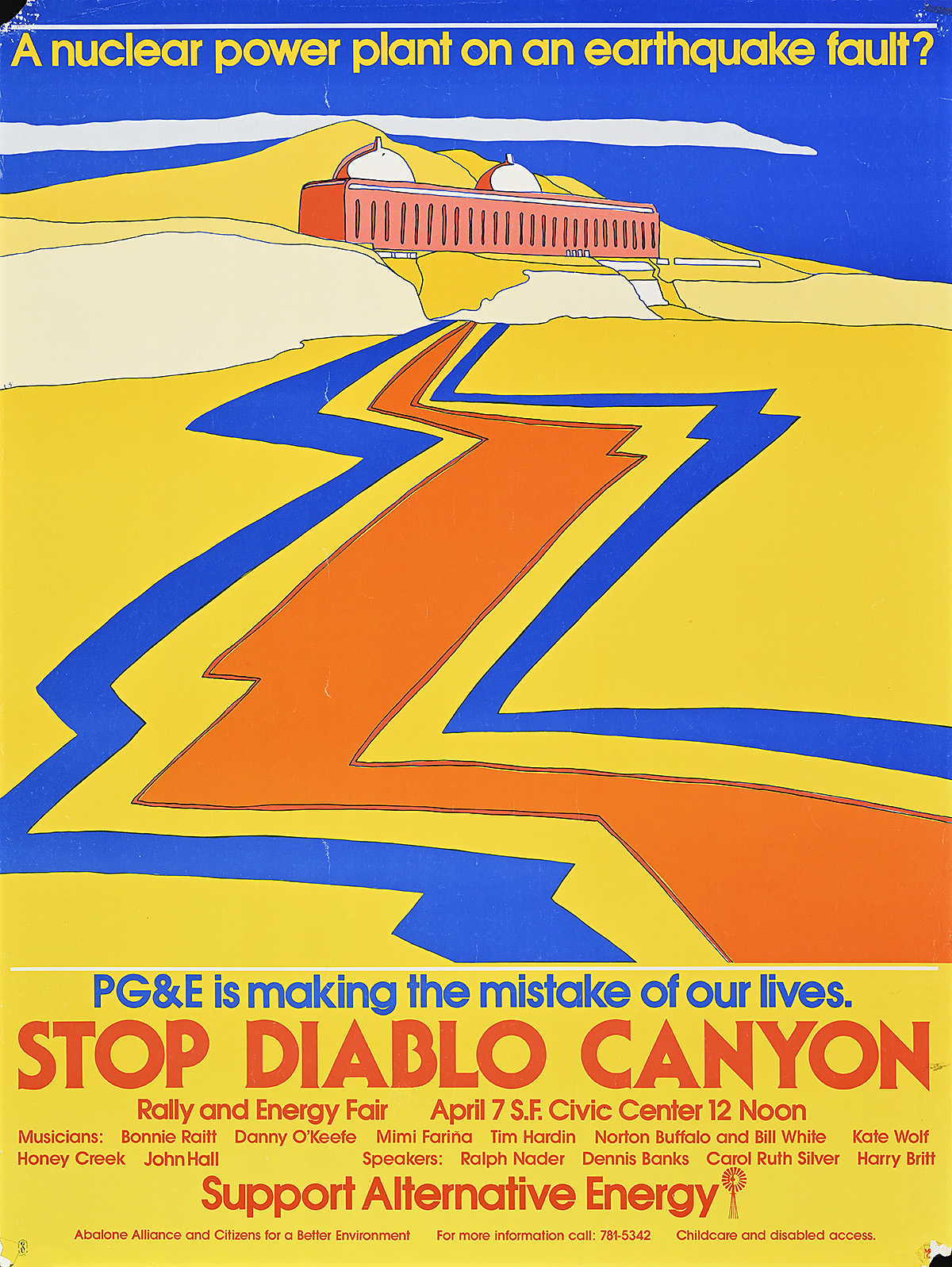

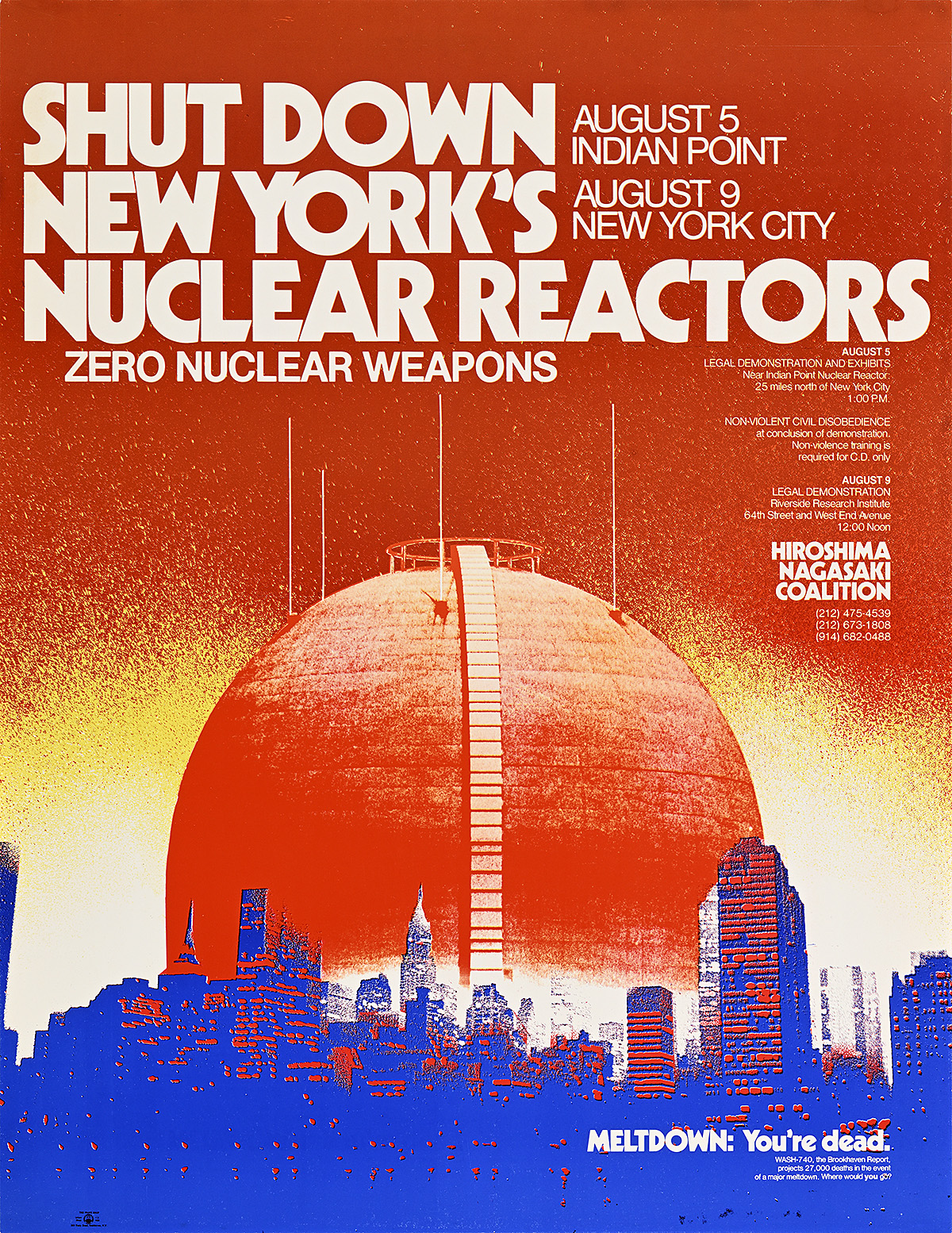

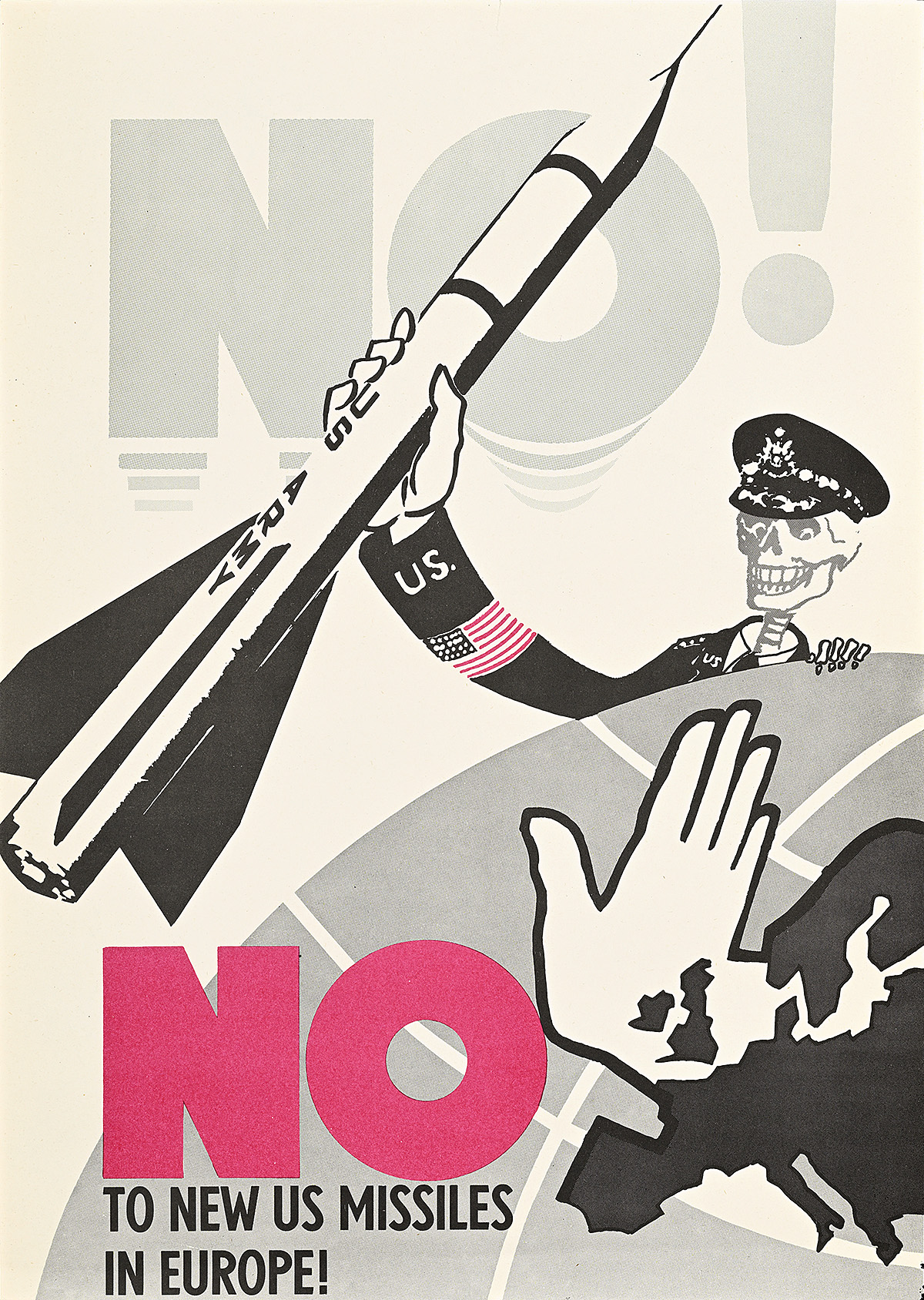

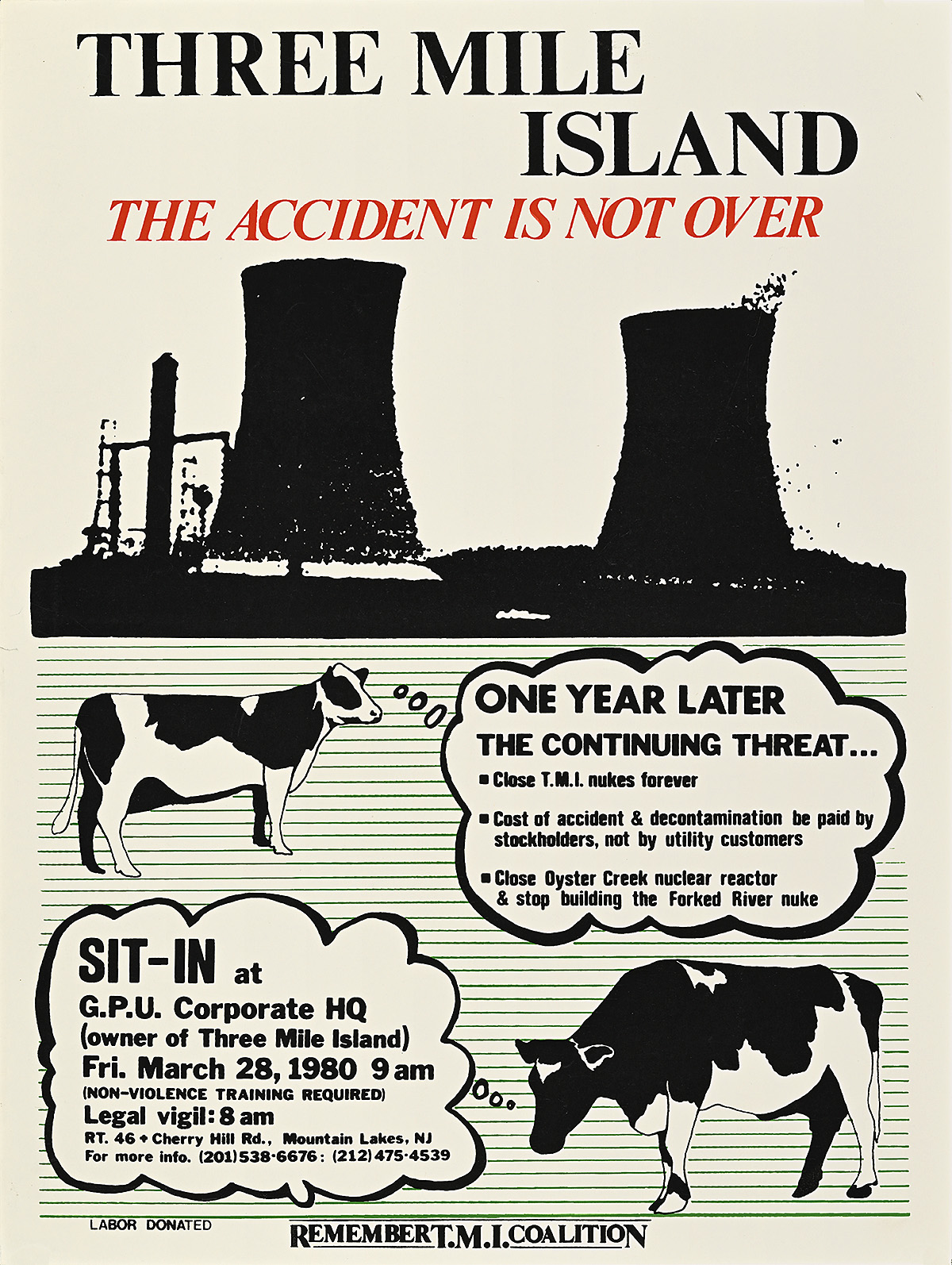

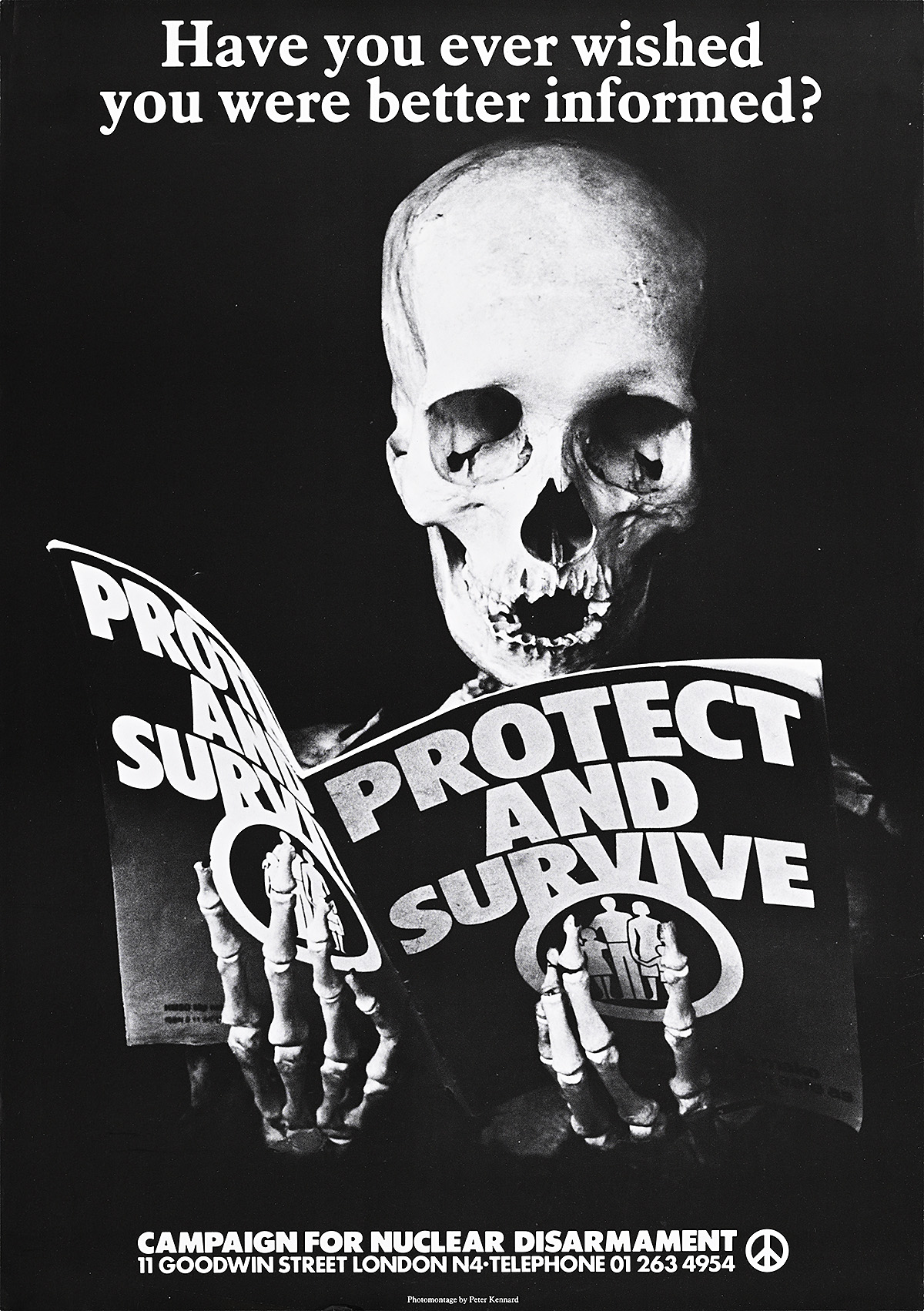

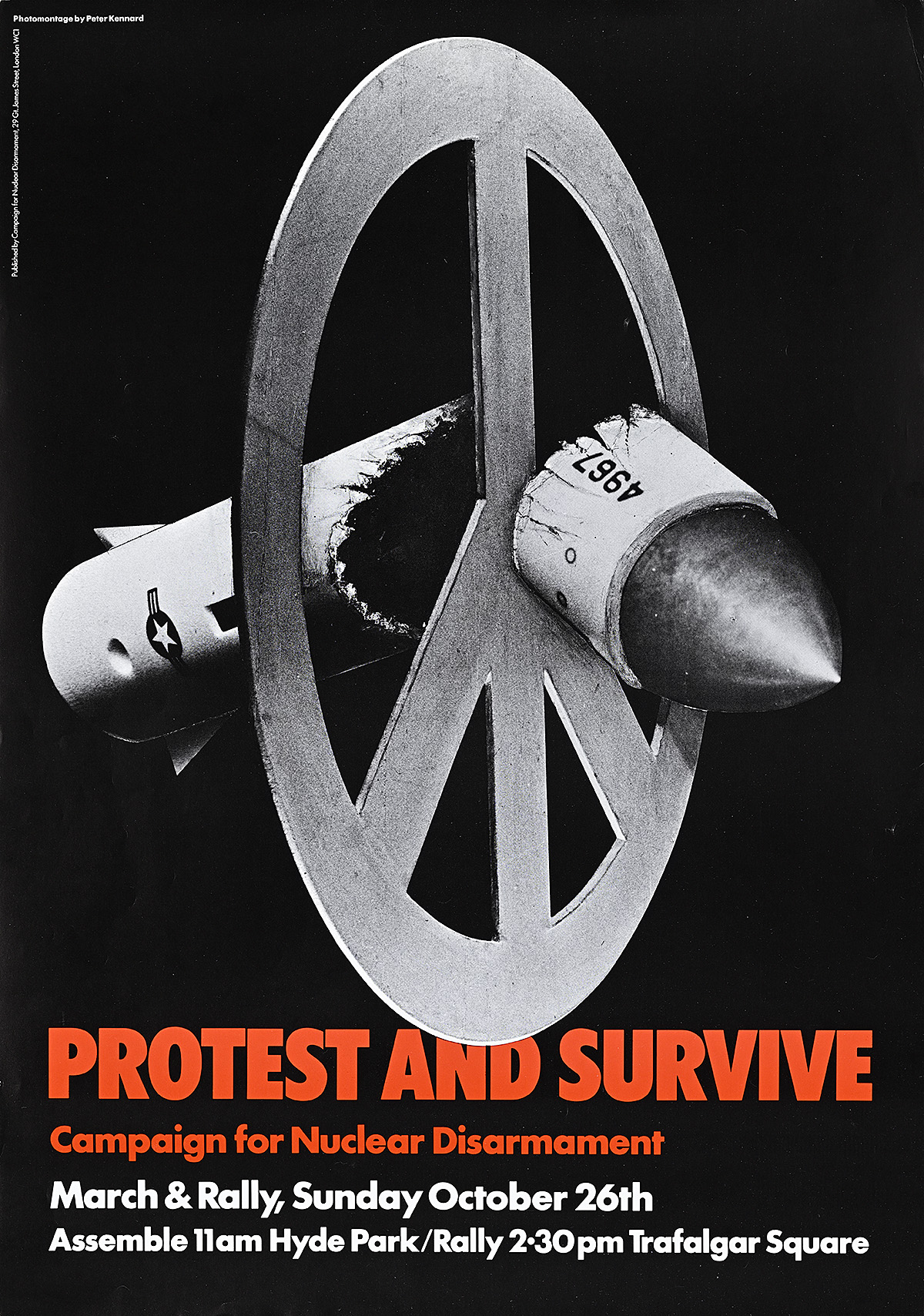

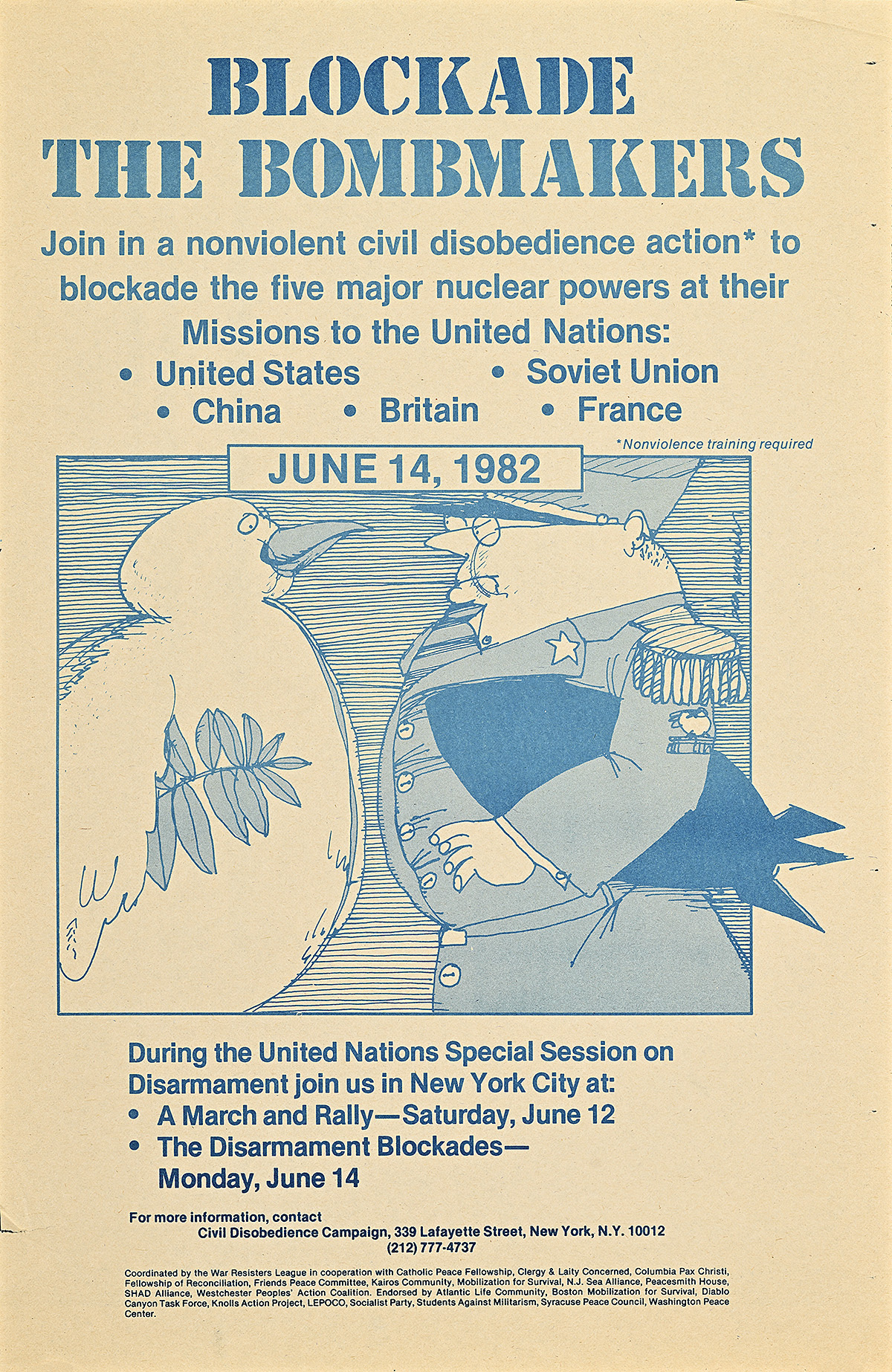

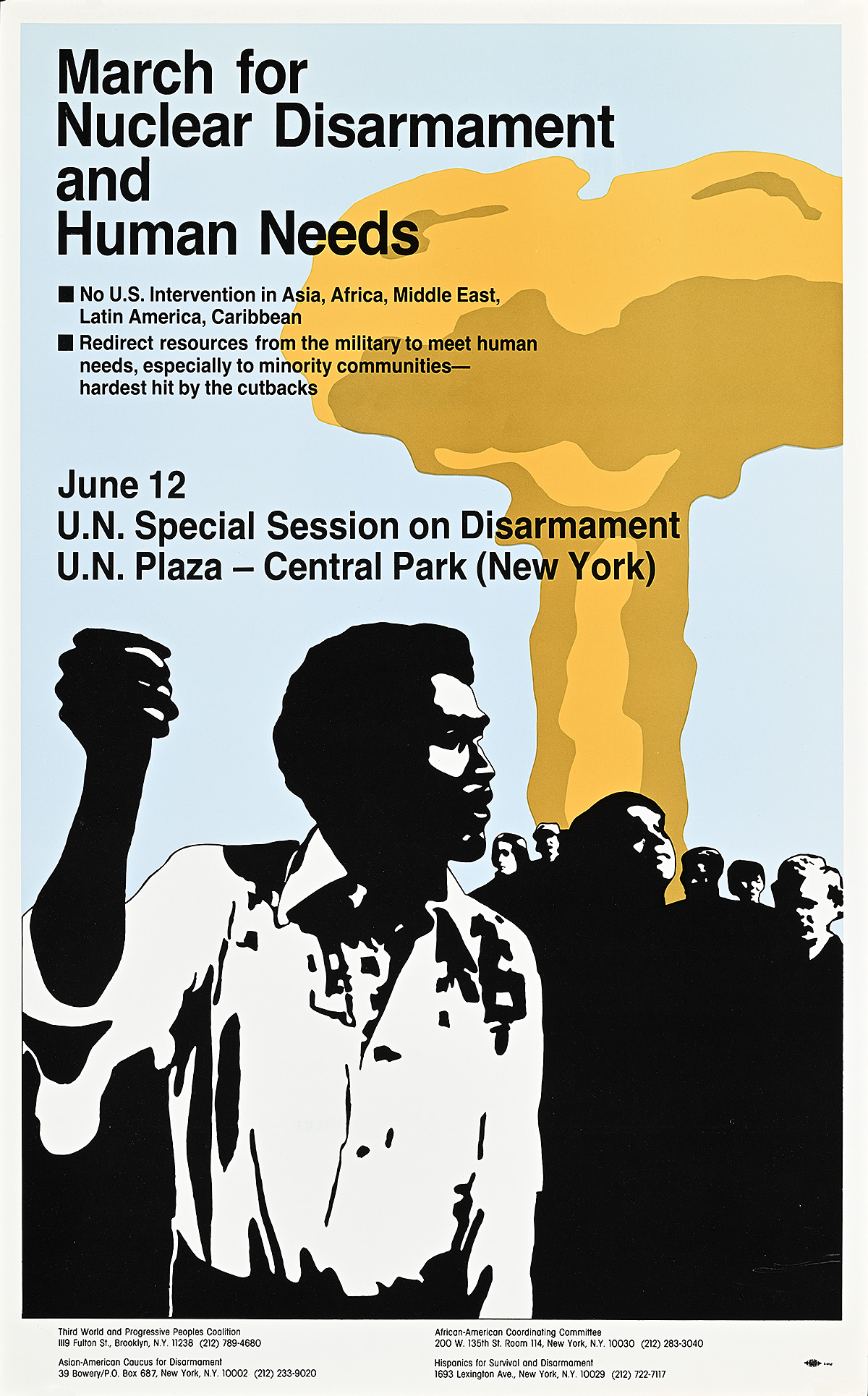

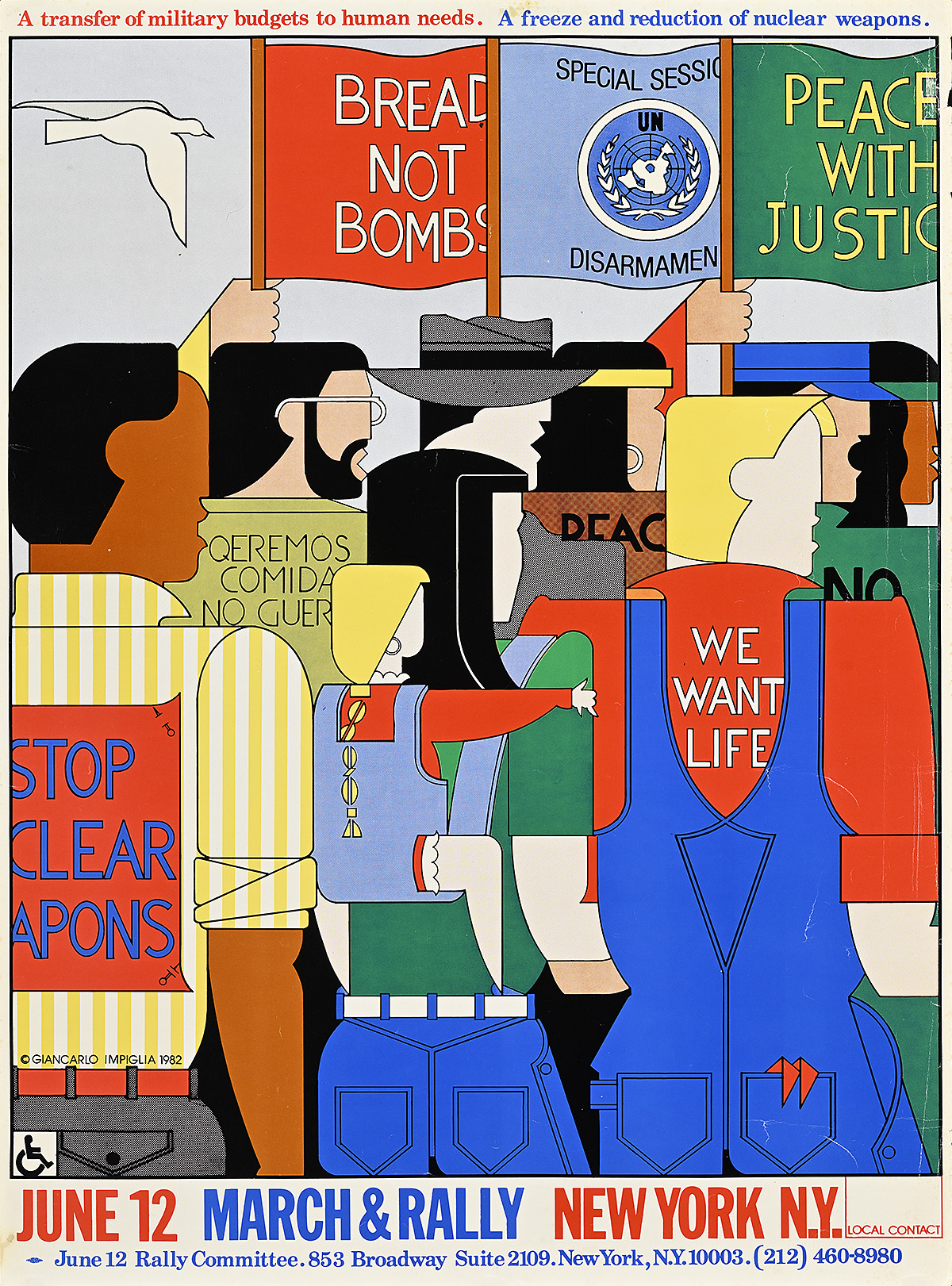

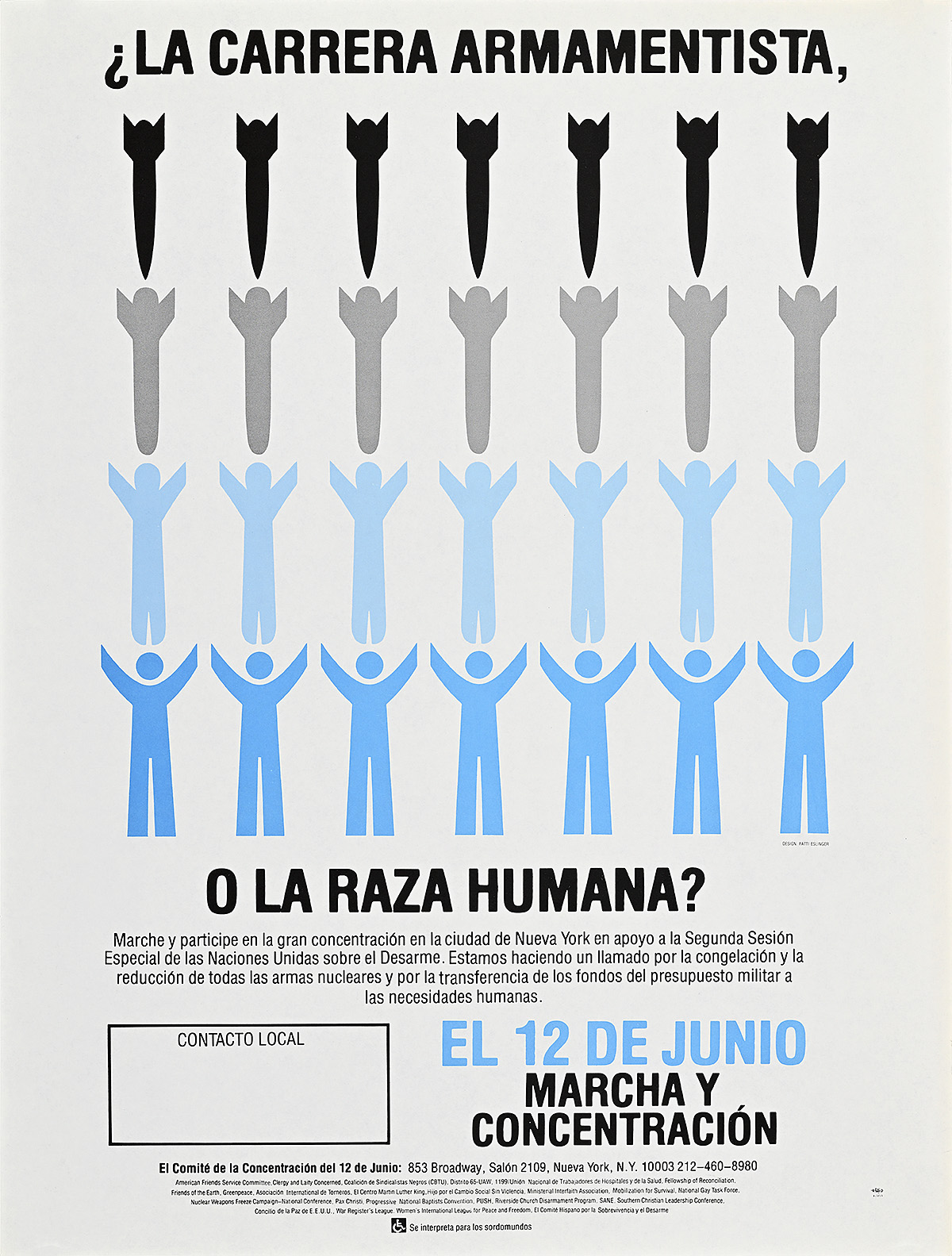

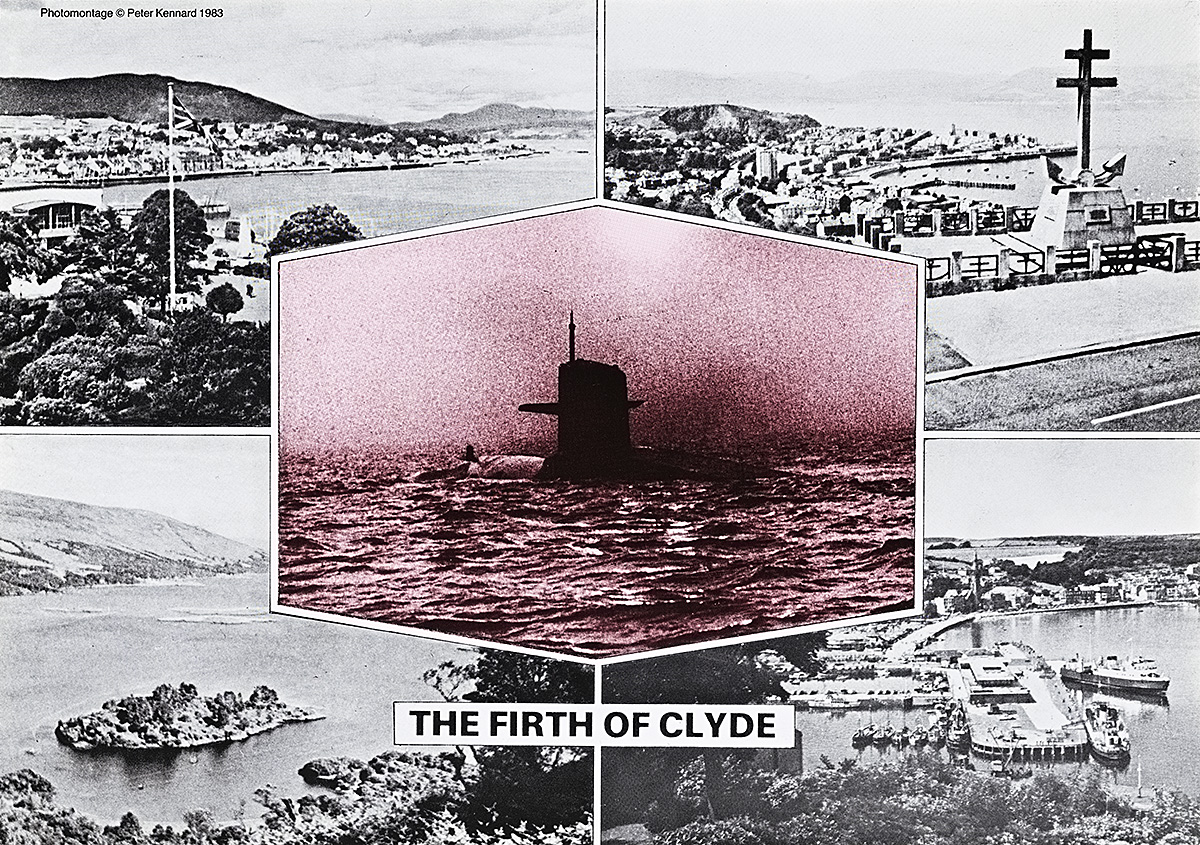

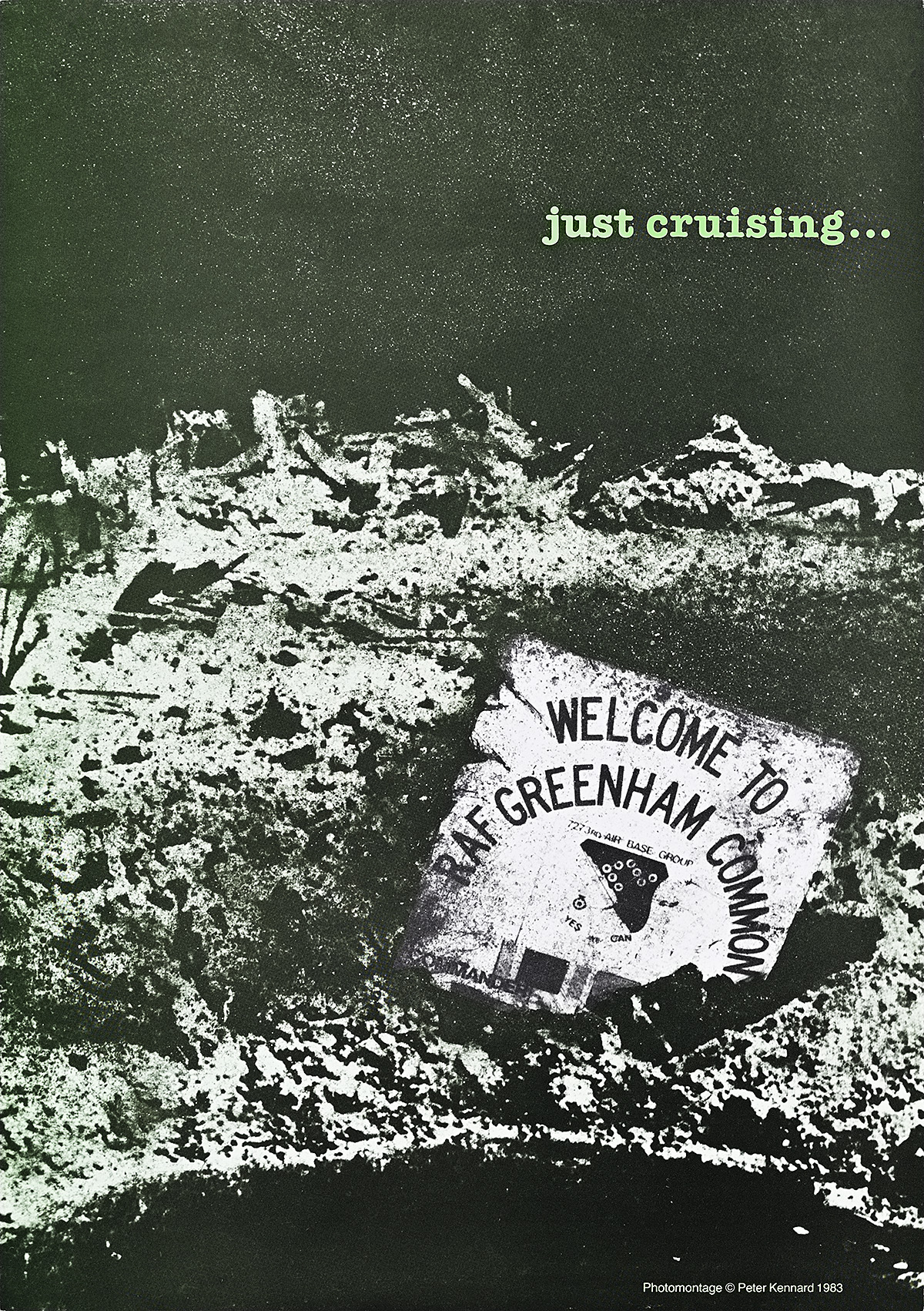

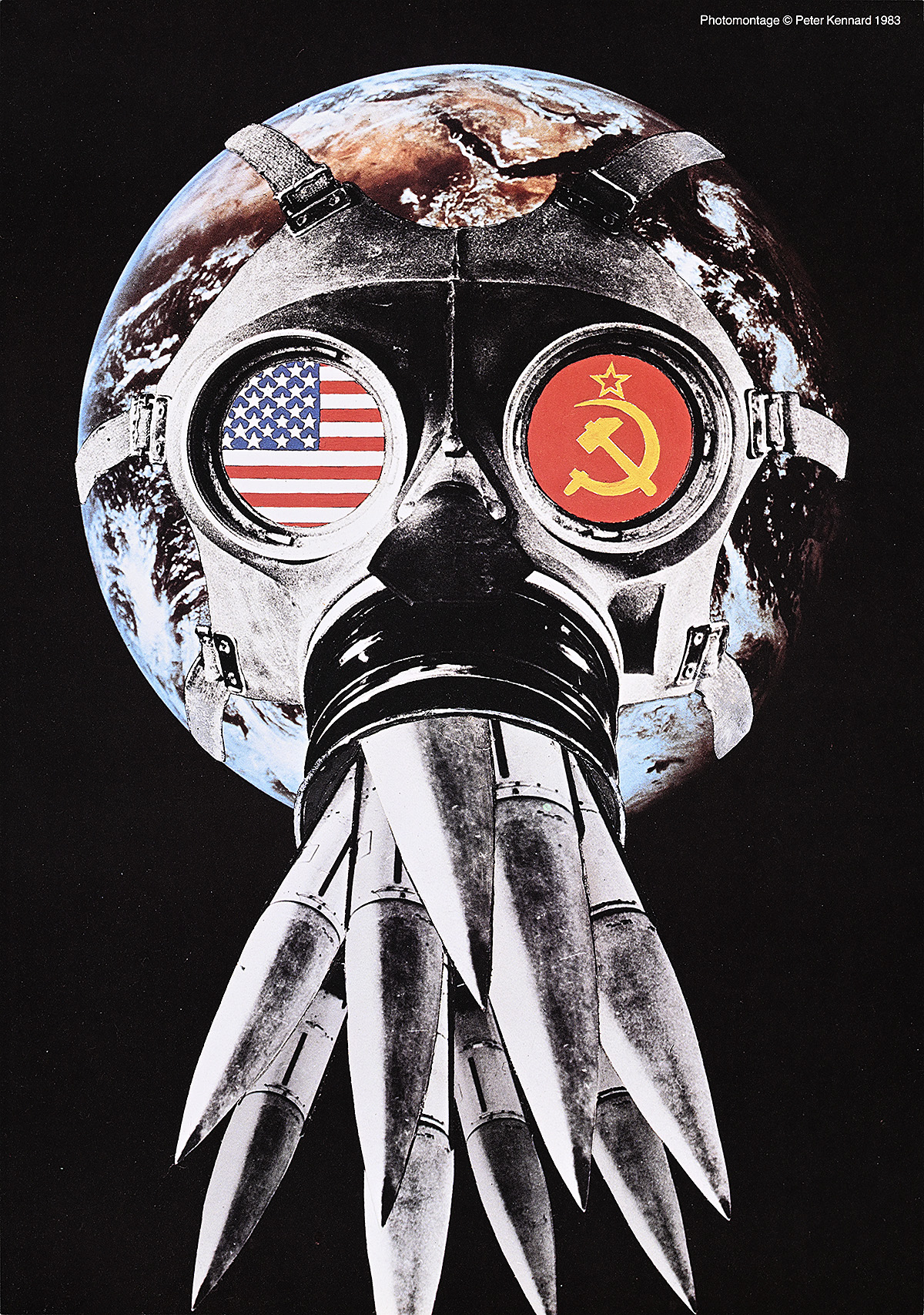

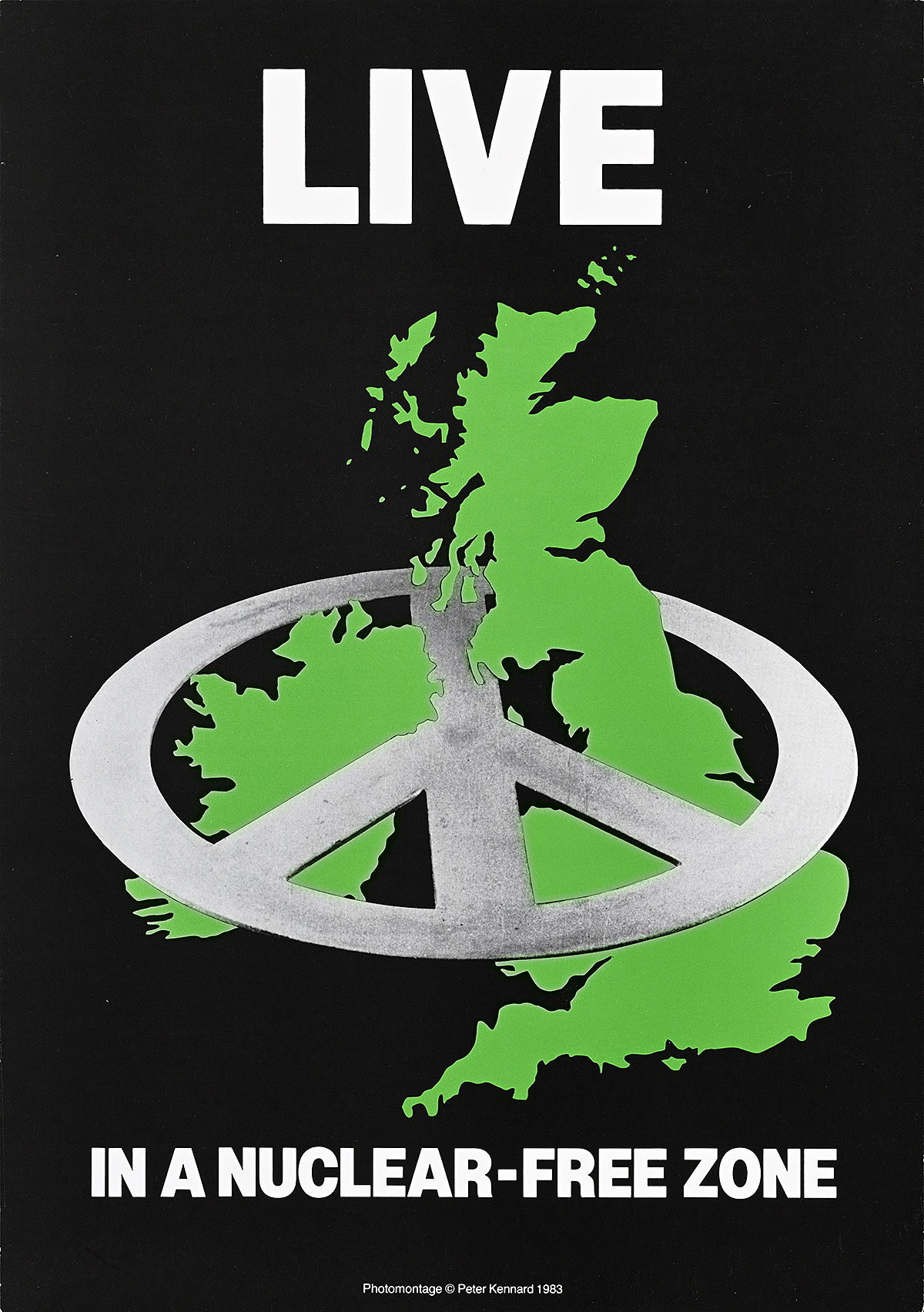

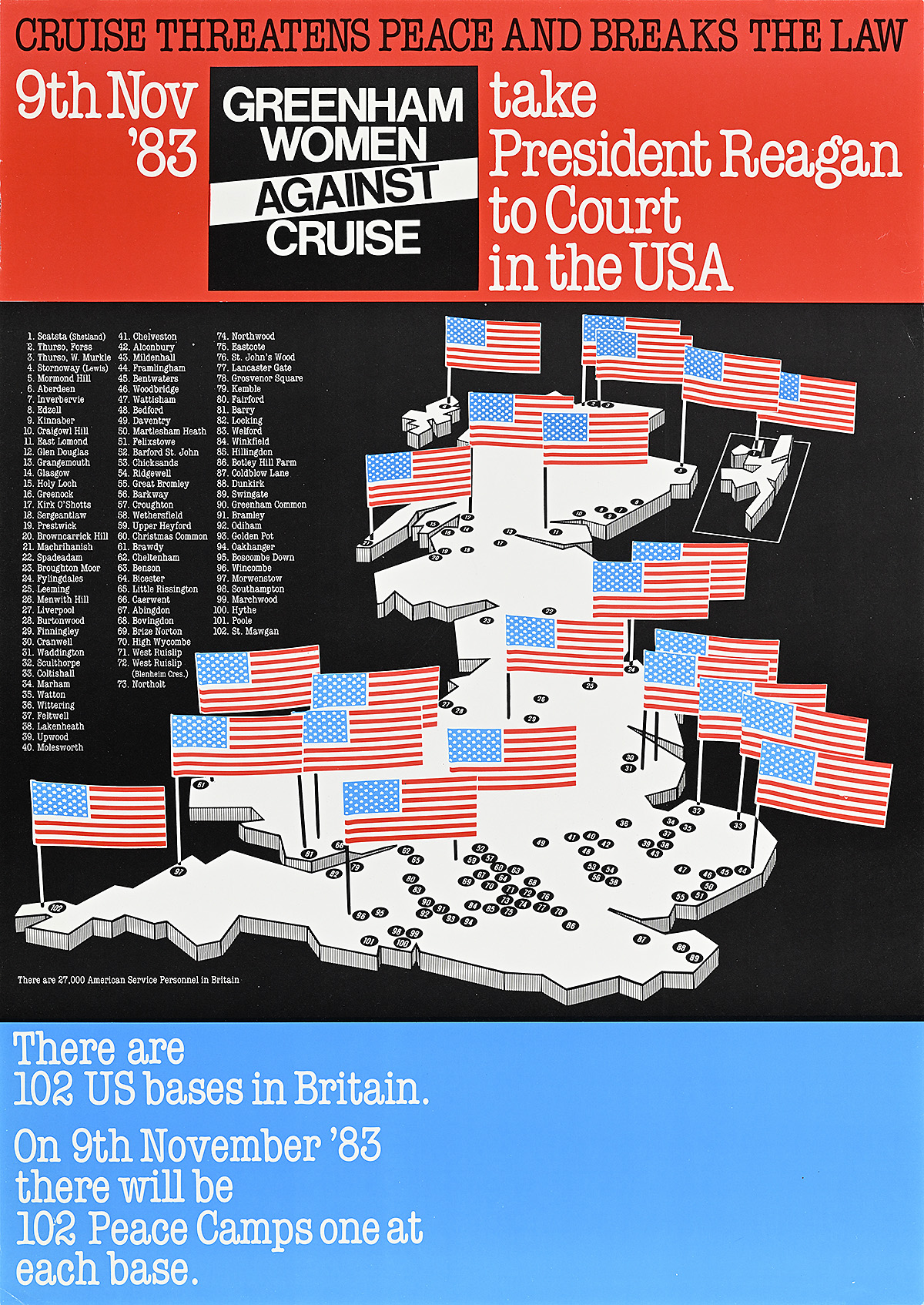

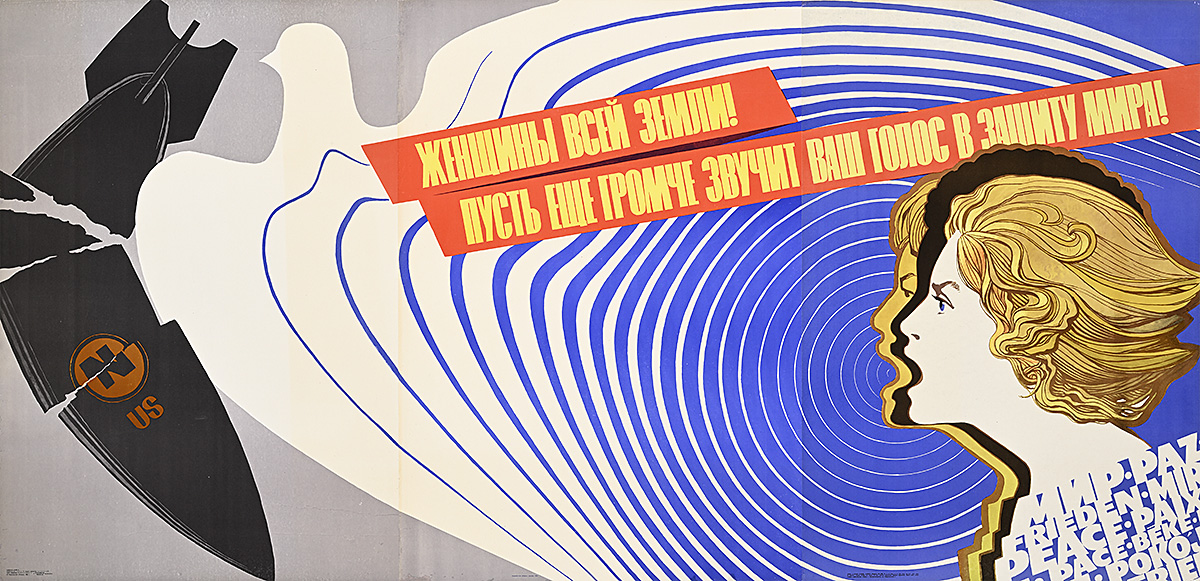

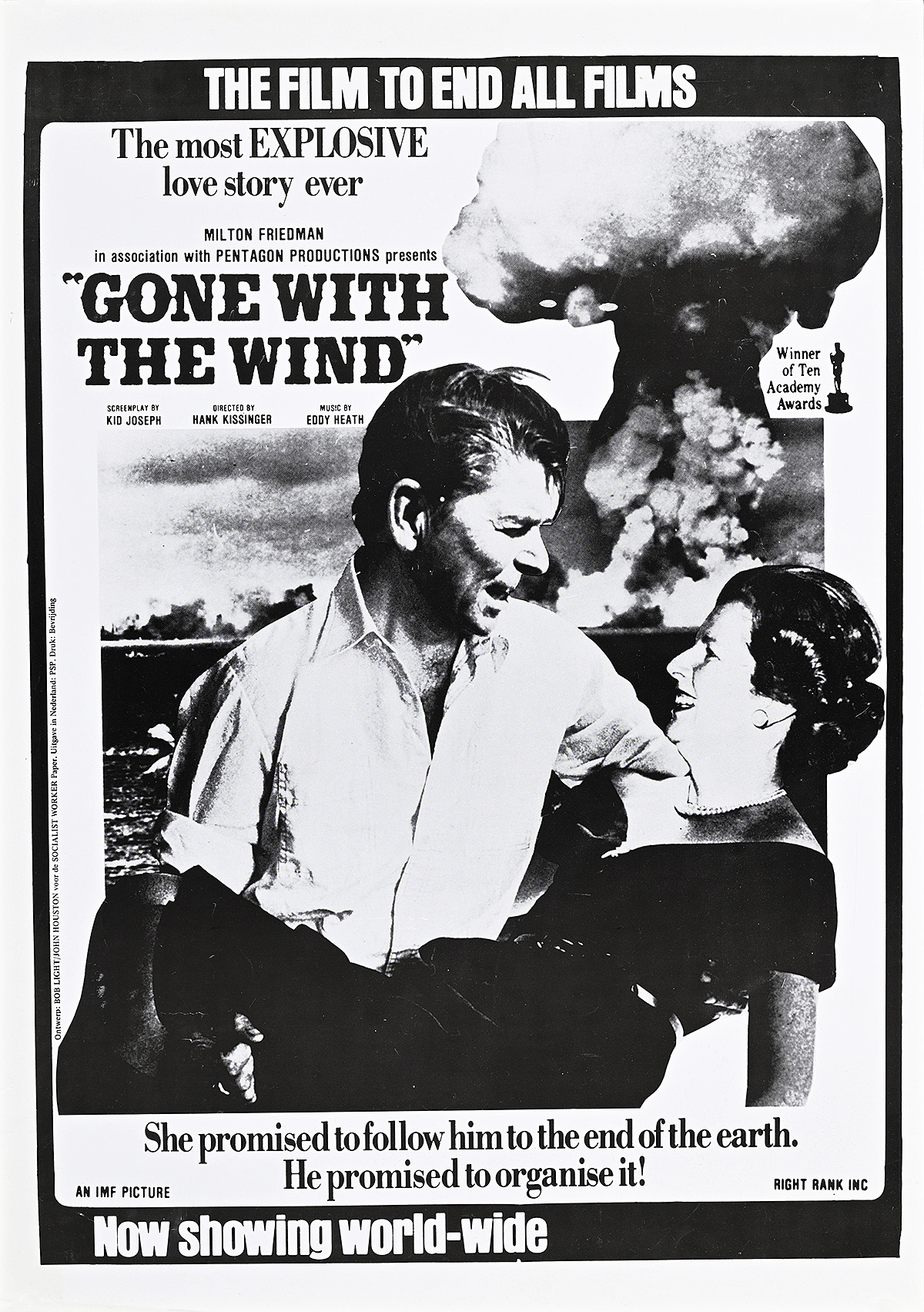

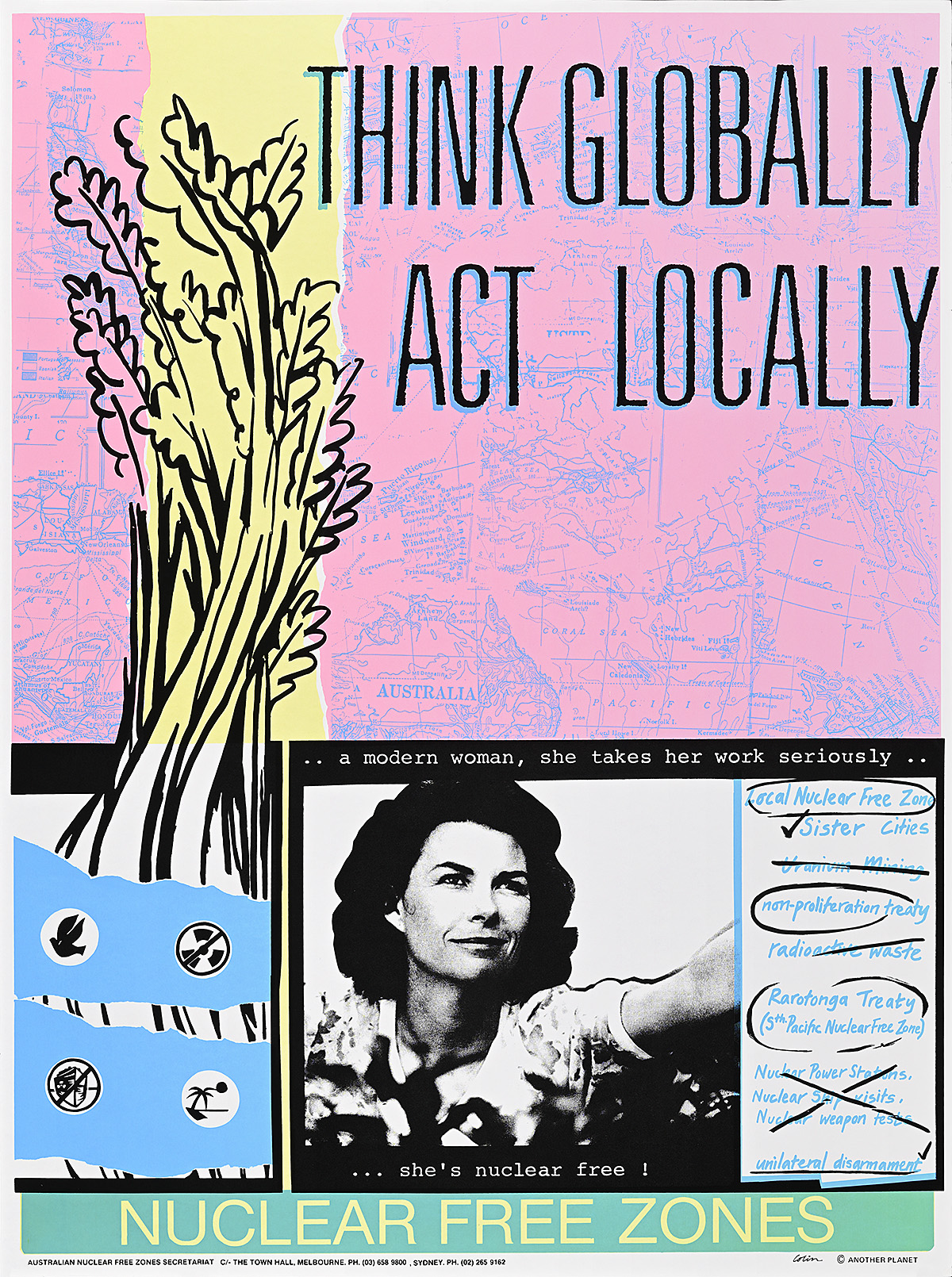

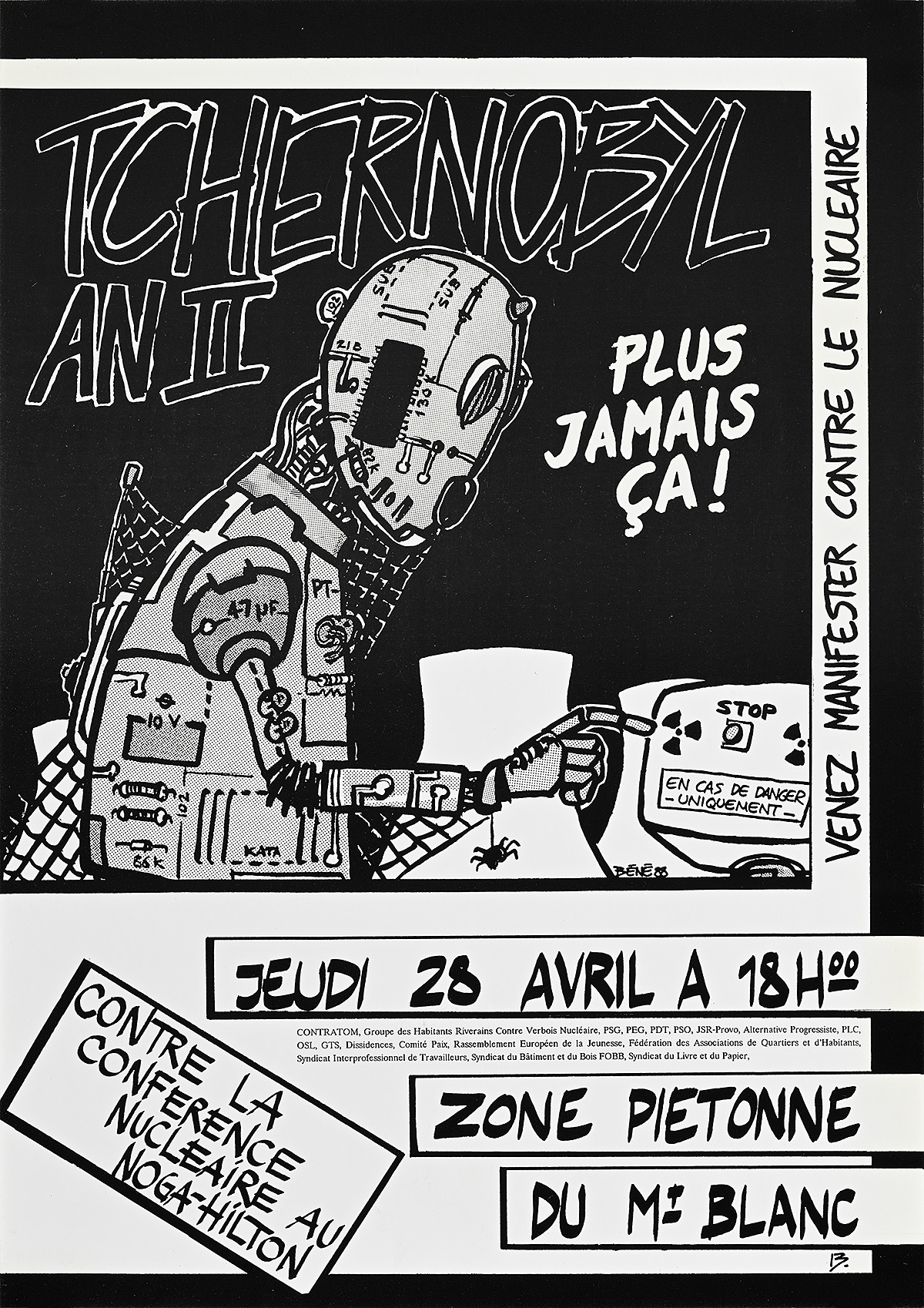

Over the next 30 years, the presence of this “alert and knowledgeable citizenry” was hardly consistent, with protests around the proliferation of nuclear weapons waxing and waning in popularity. The first wave of major public activism began with the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, when the United States discovered that the Soviet Union was building nuclear missile sites on Cuba. The resulting confrontation between the two nations brought the world to the edge of a nuclear holocaust. The next major upsurge in demonstrations came with the elections of Margaret Thatcher in England in 1979 and Ronald Reagan in the United States in 1980, as both leaders believed in increasing their nation’s stockpiles of nuclear weapons in the name of national security.

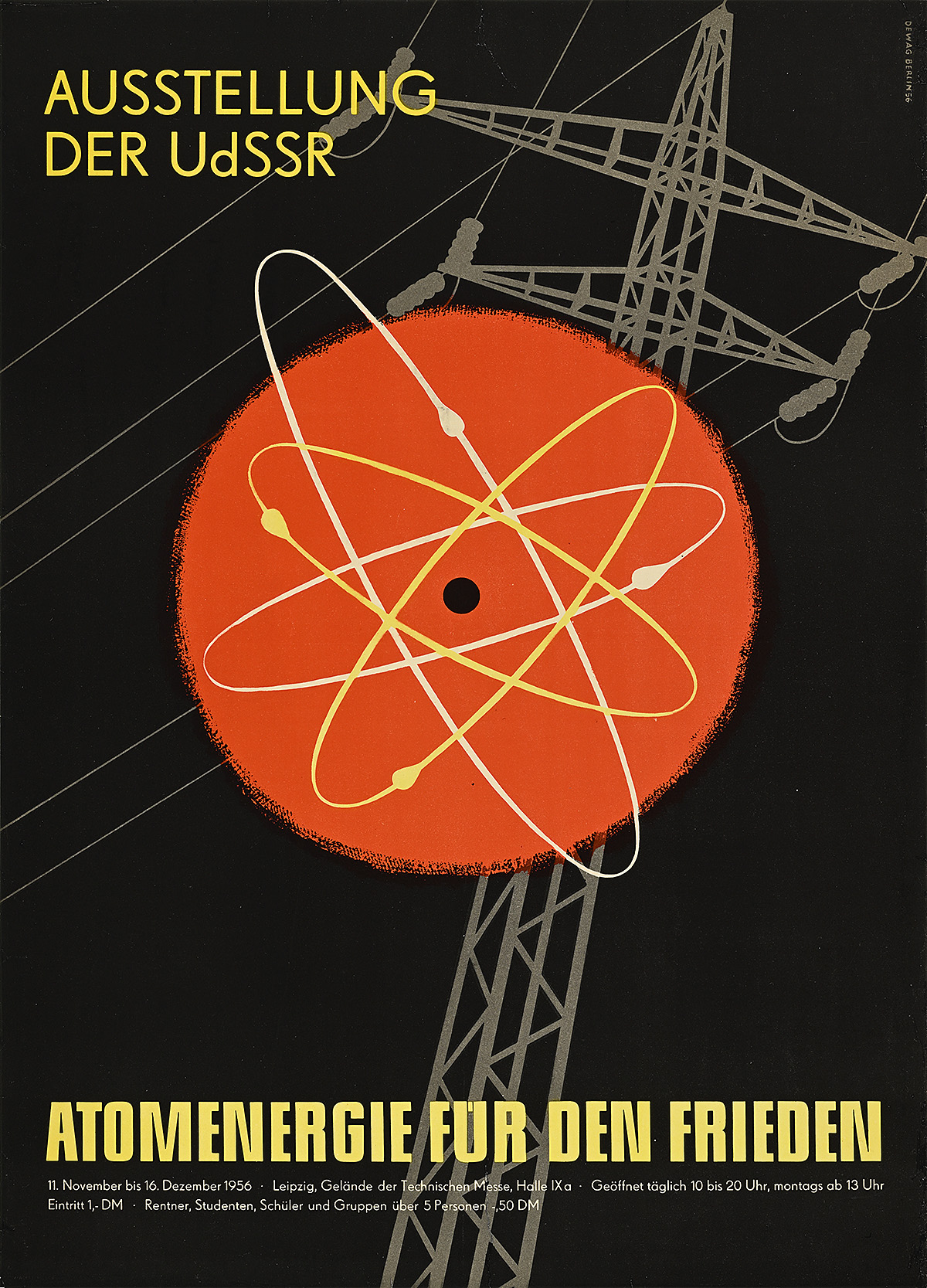

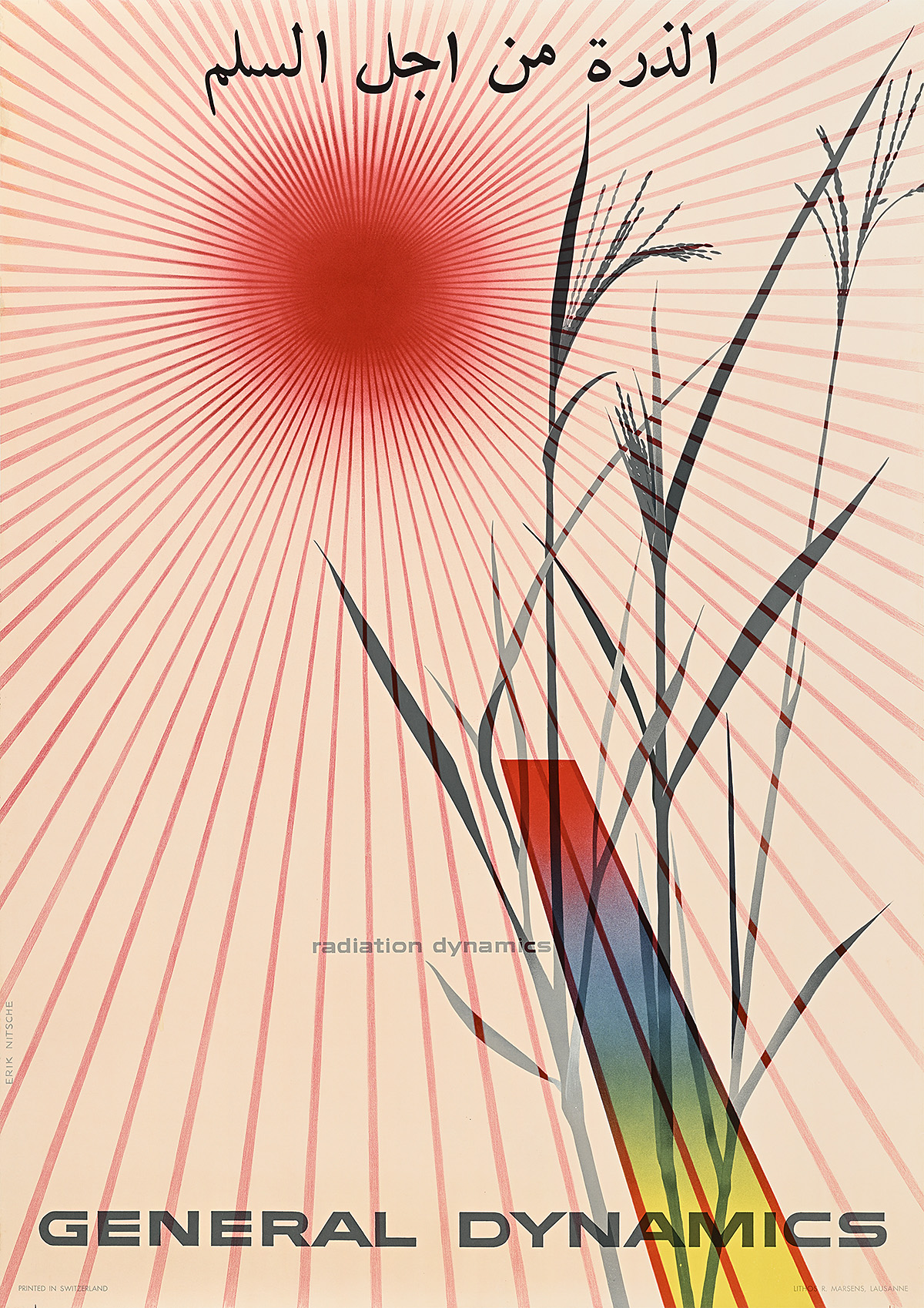

When Mikhail Gorbachev became general secretary of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union in 1985, he noted that the survival of mankind would depend on a rethinking of this kind of escalating defense strategy. Influenced by scientists and antiwar organizations, as well as the collapsing Soviet economy, he began to reduce the Soviet arsenal and suggested that the United States do the same. While President Reagan was initially hesitant, his gradual reevaluation of the realities of nuclear war, combined with his awareness of Gorbachev’s popularity in the United Kingdom and West Germany on issues of arms control, persuaded him to sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in December 1987, reducing the quantity of nuclear weapons in both the United States and the U.S.S.R. A year later, South Africa divested its nuclear arsenal. Further disarmament milestones were reached in 1990, when the Soviet Union conducted its final nuclear test in an underground facility near the Matochkin Strait; the United States’s final test took place underground in Nevada in September 1992—its 1,032nd test since 1945. That same year, the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was presented to the United Nations General Assembly, asking all countries to ban nuclear testing. While it was adopted by the U.N. in September 1996, little progress has been made since then, with only 178 nations ratifying it.

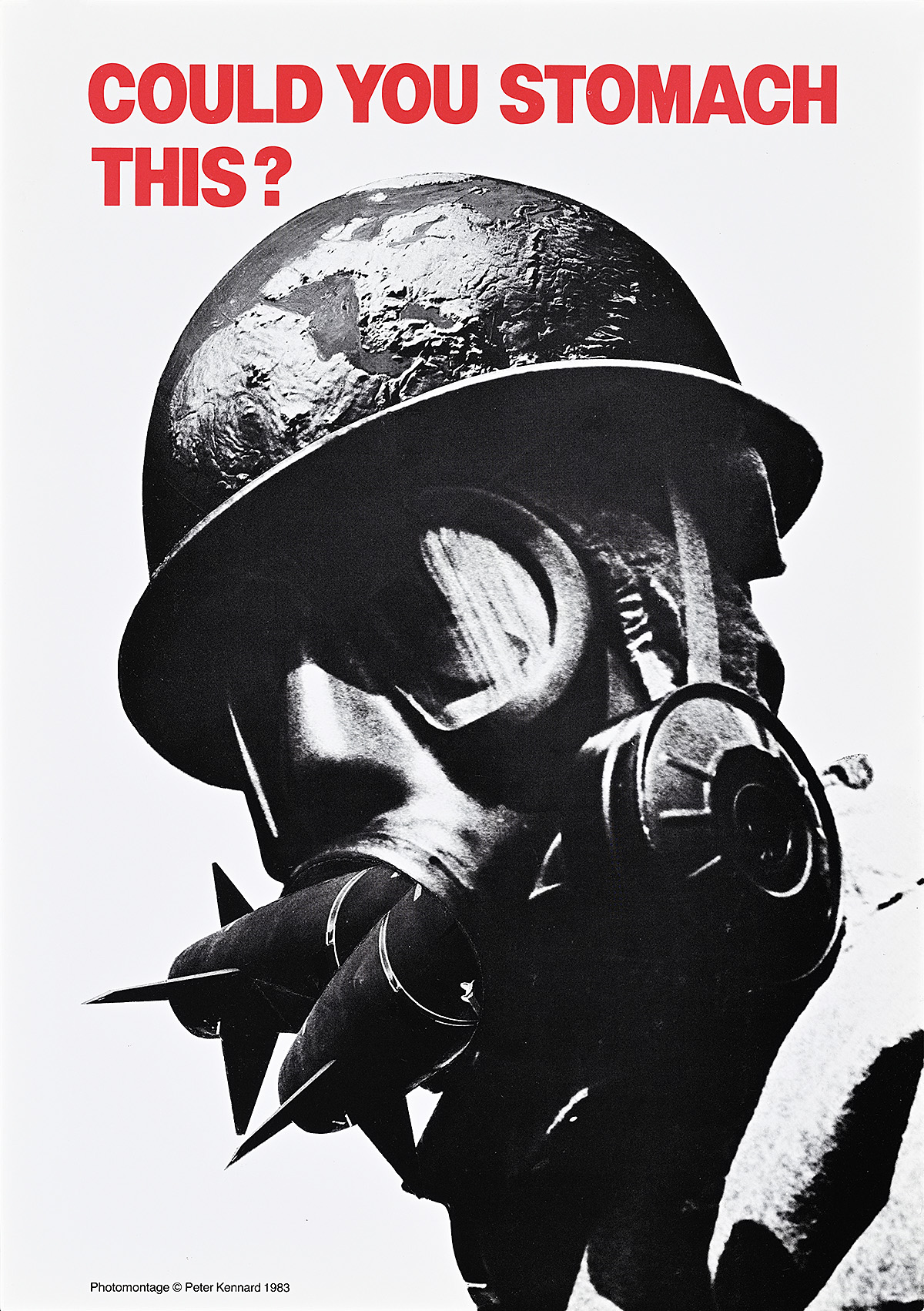

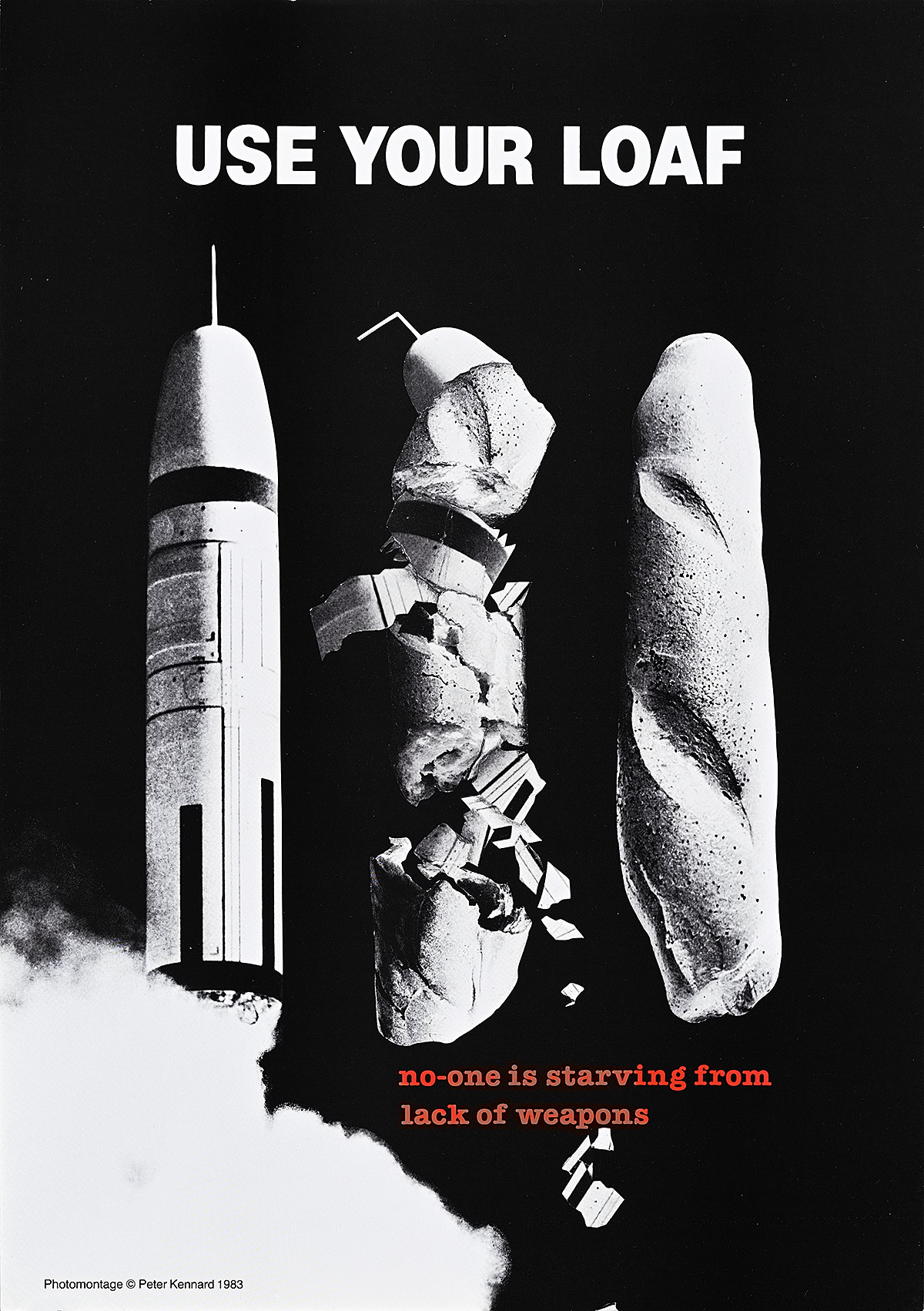

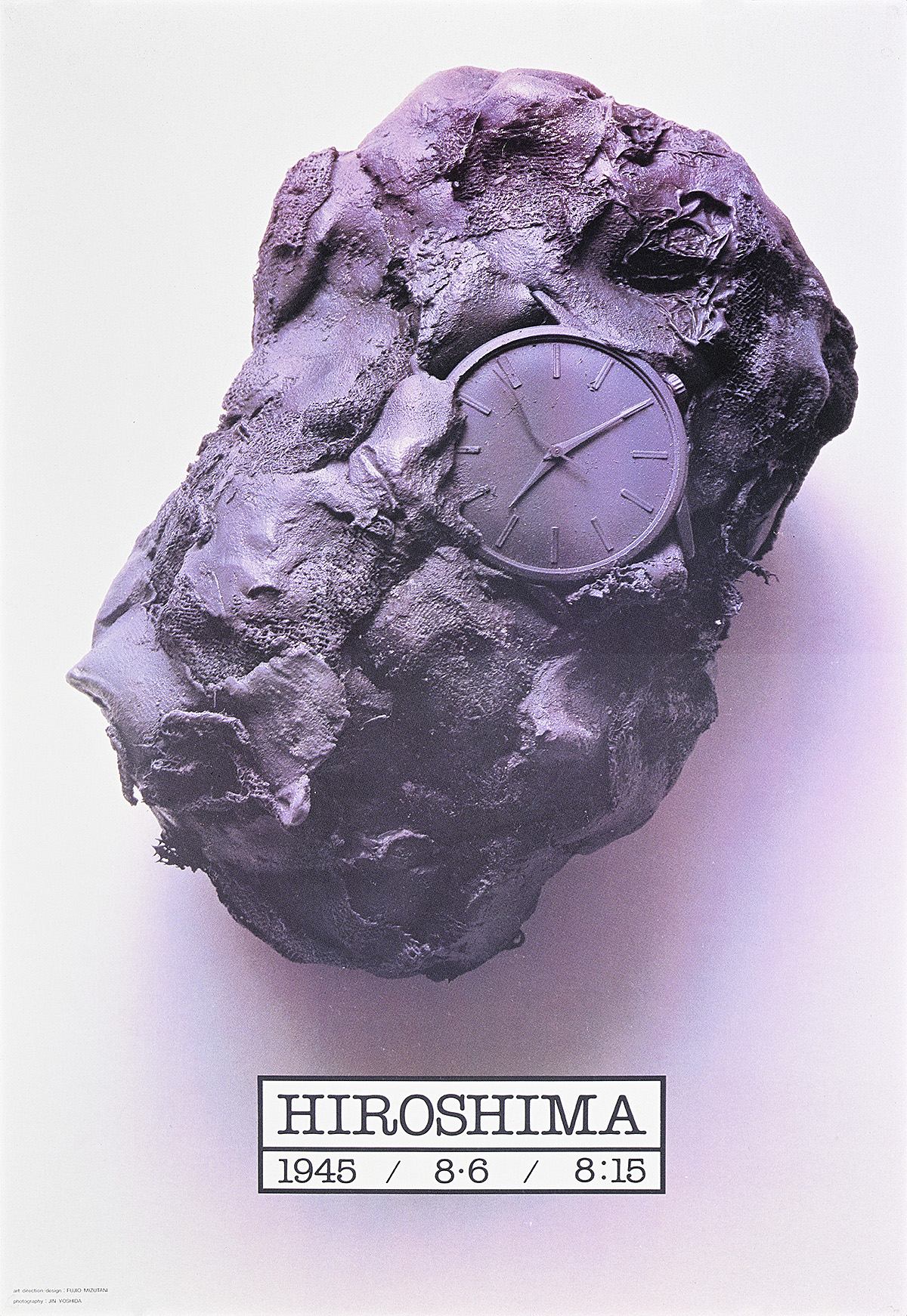

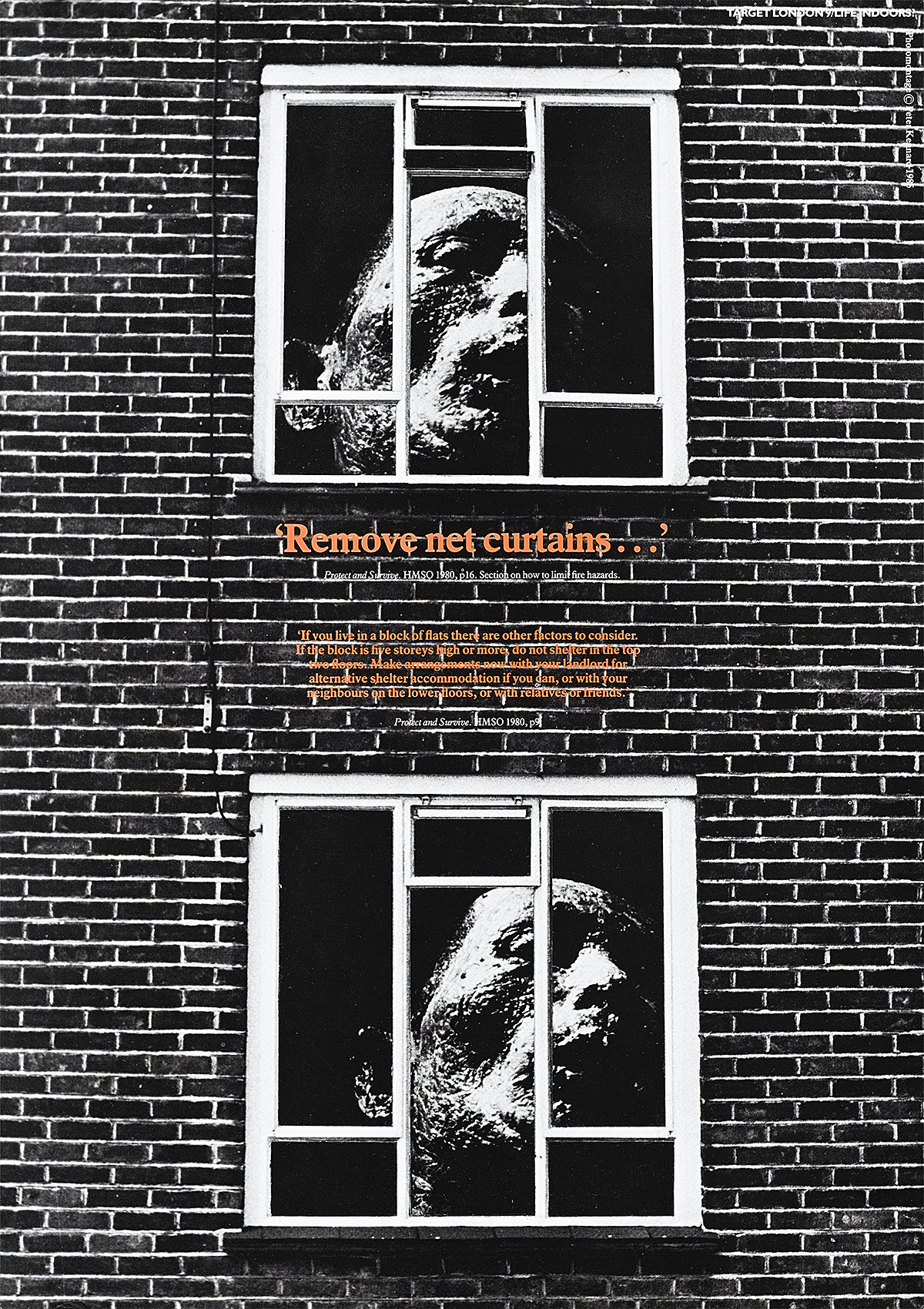

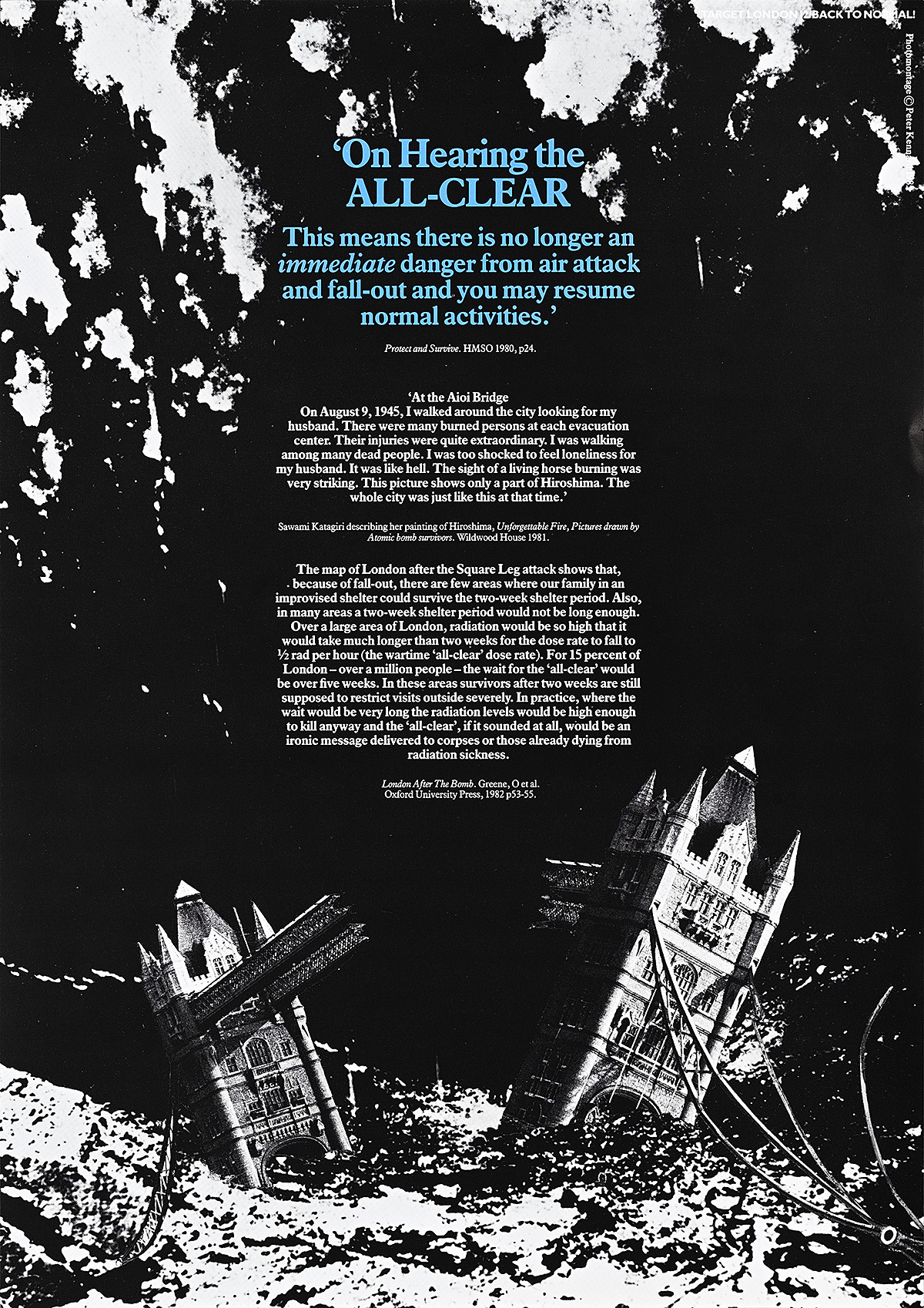

“In a nuclear war in Europe, at least 100 million people would die. If the USA and the USSR were engaged in a full-scale nuclear war, at least 200 million people would perish.”—Peter Kennard, designer