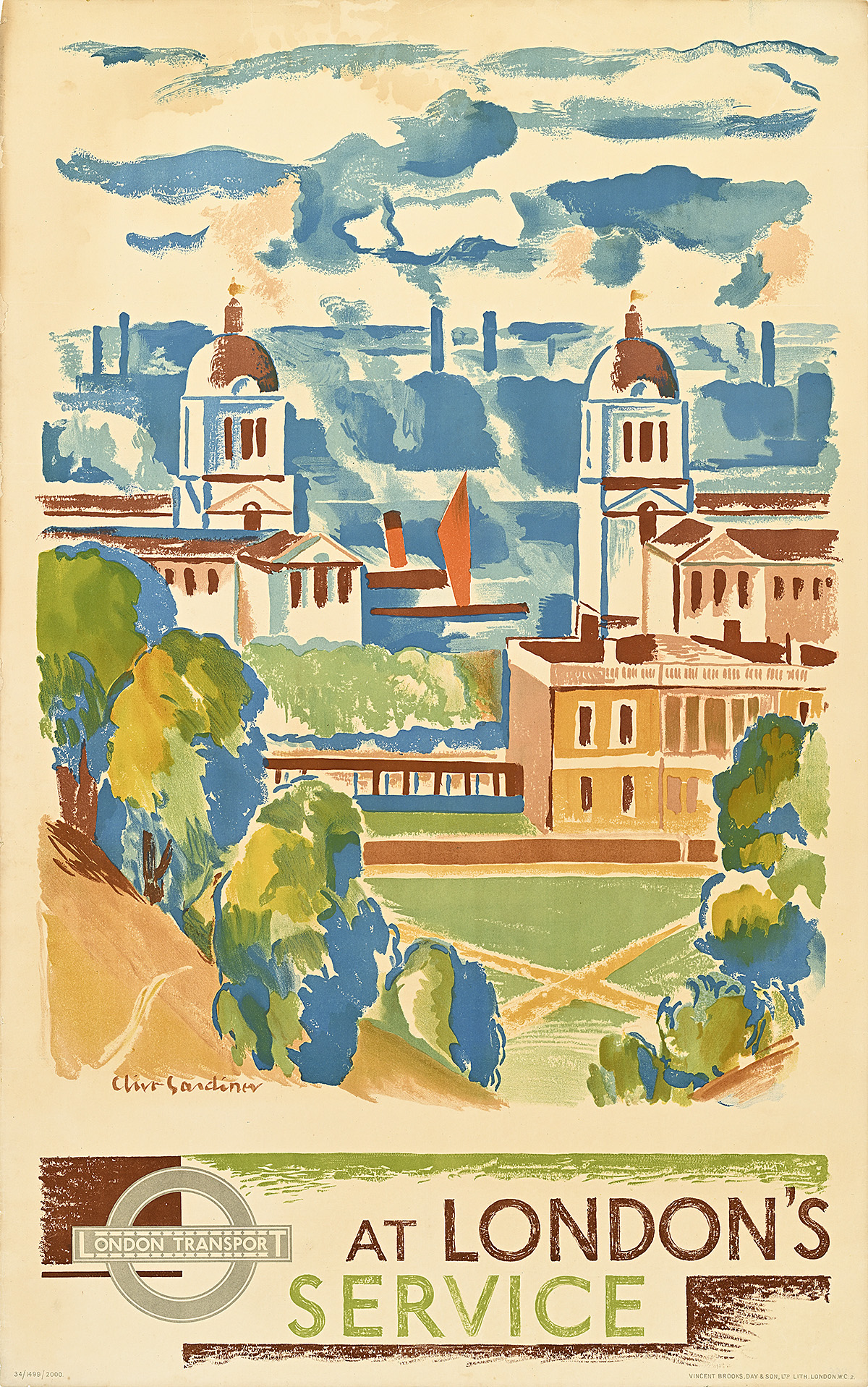

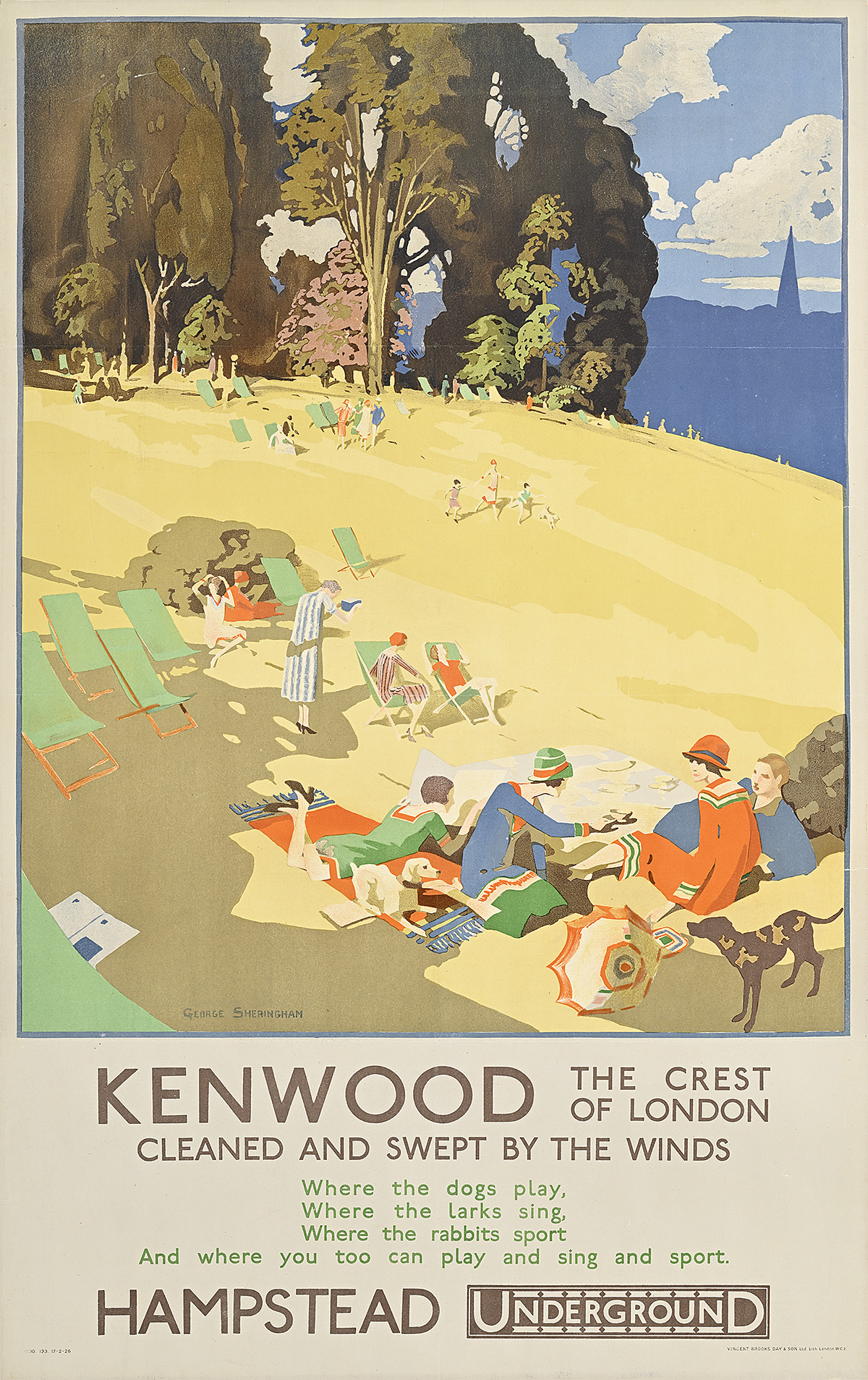

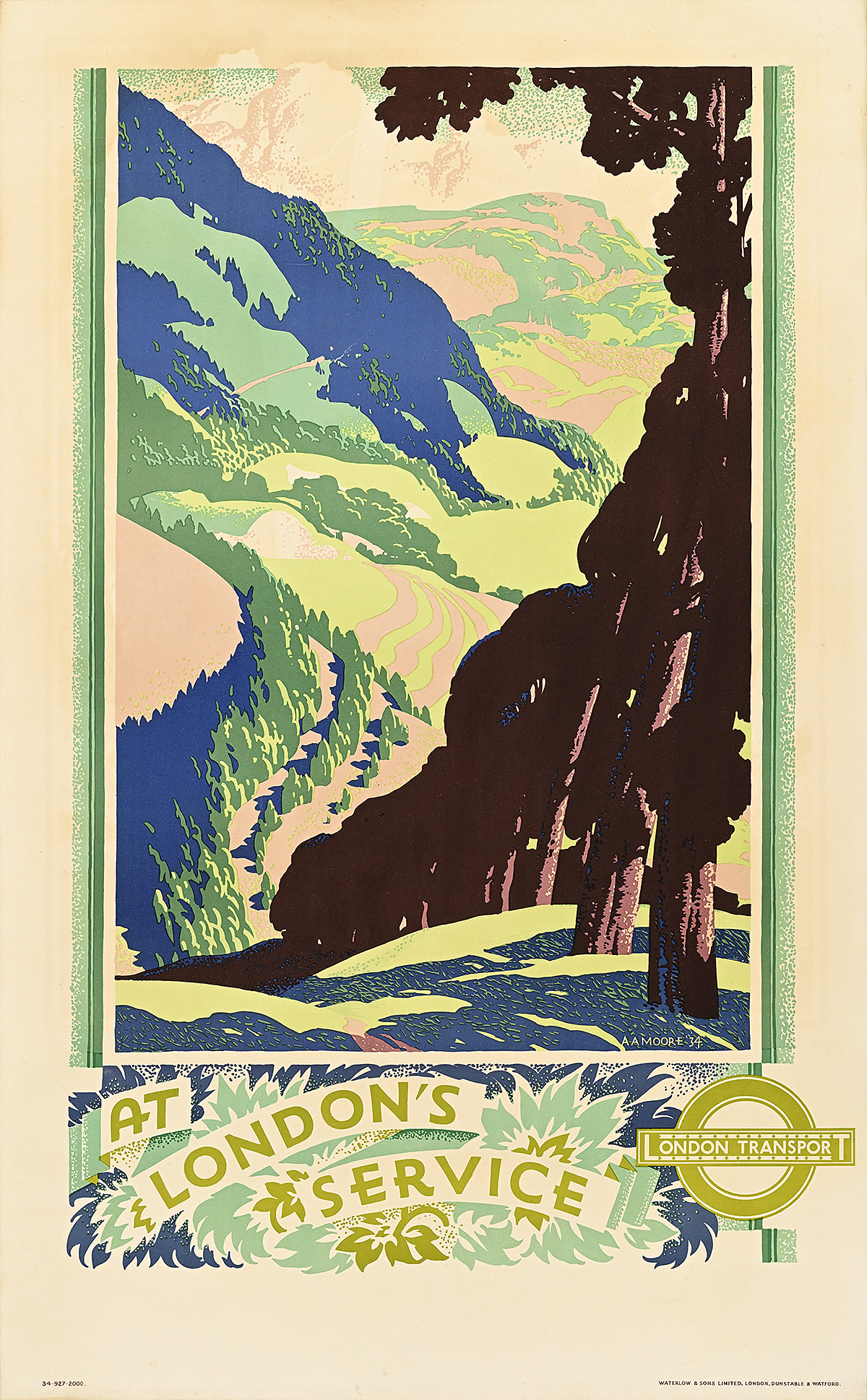

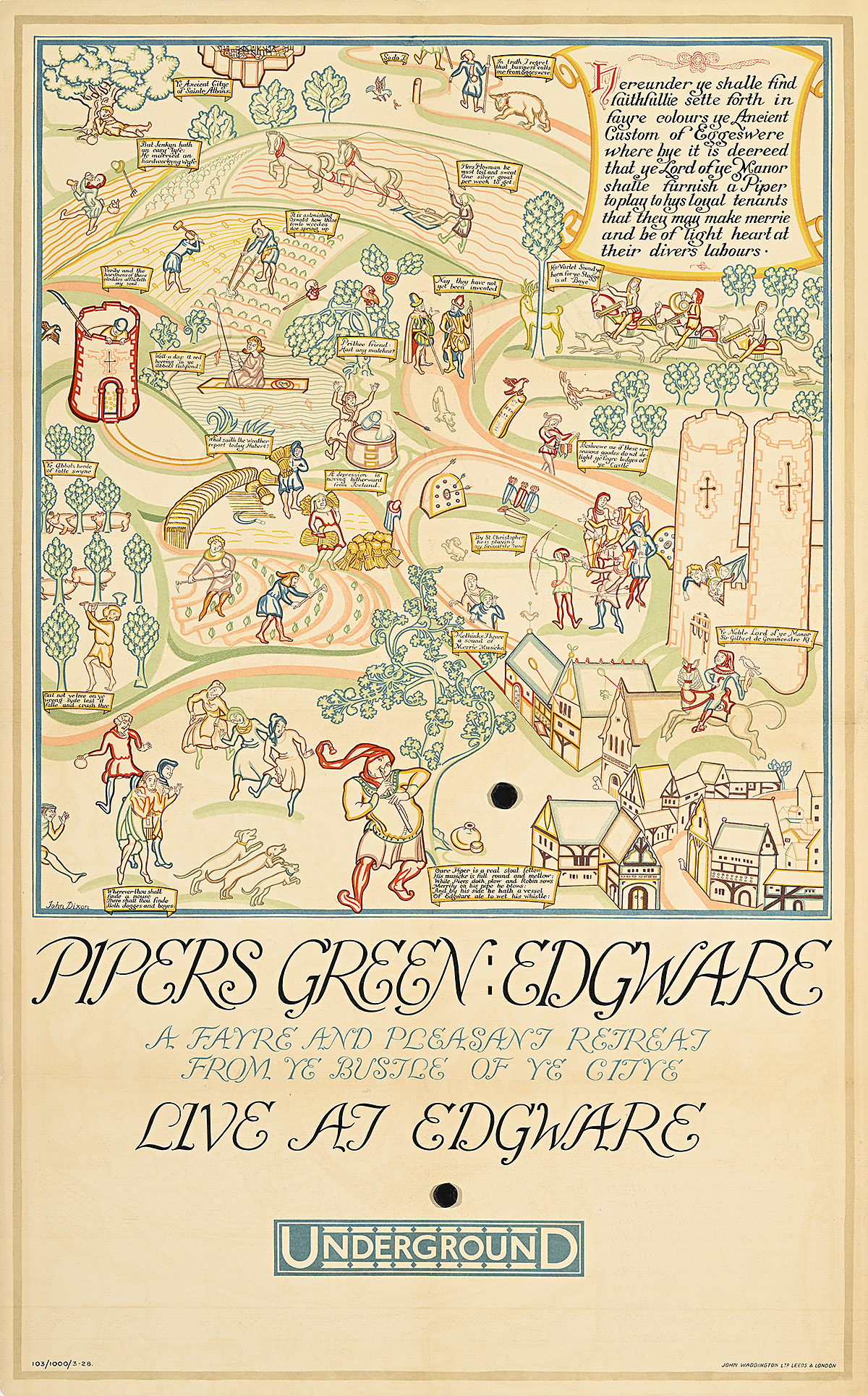

Leaving the Smoke Behind: Enjoying an Awayday

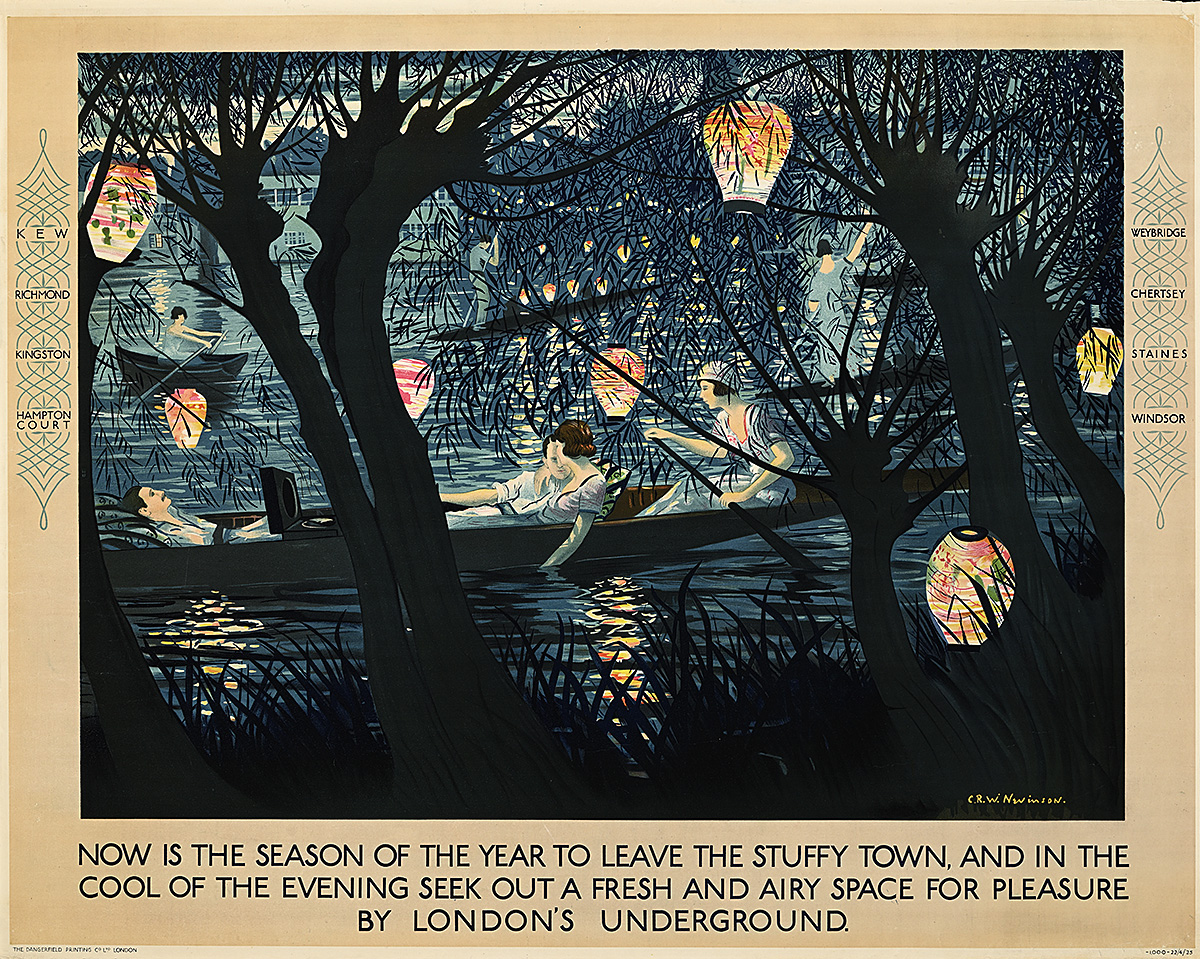

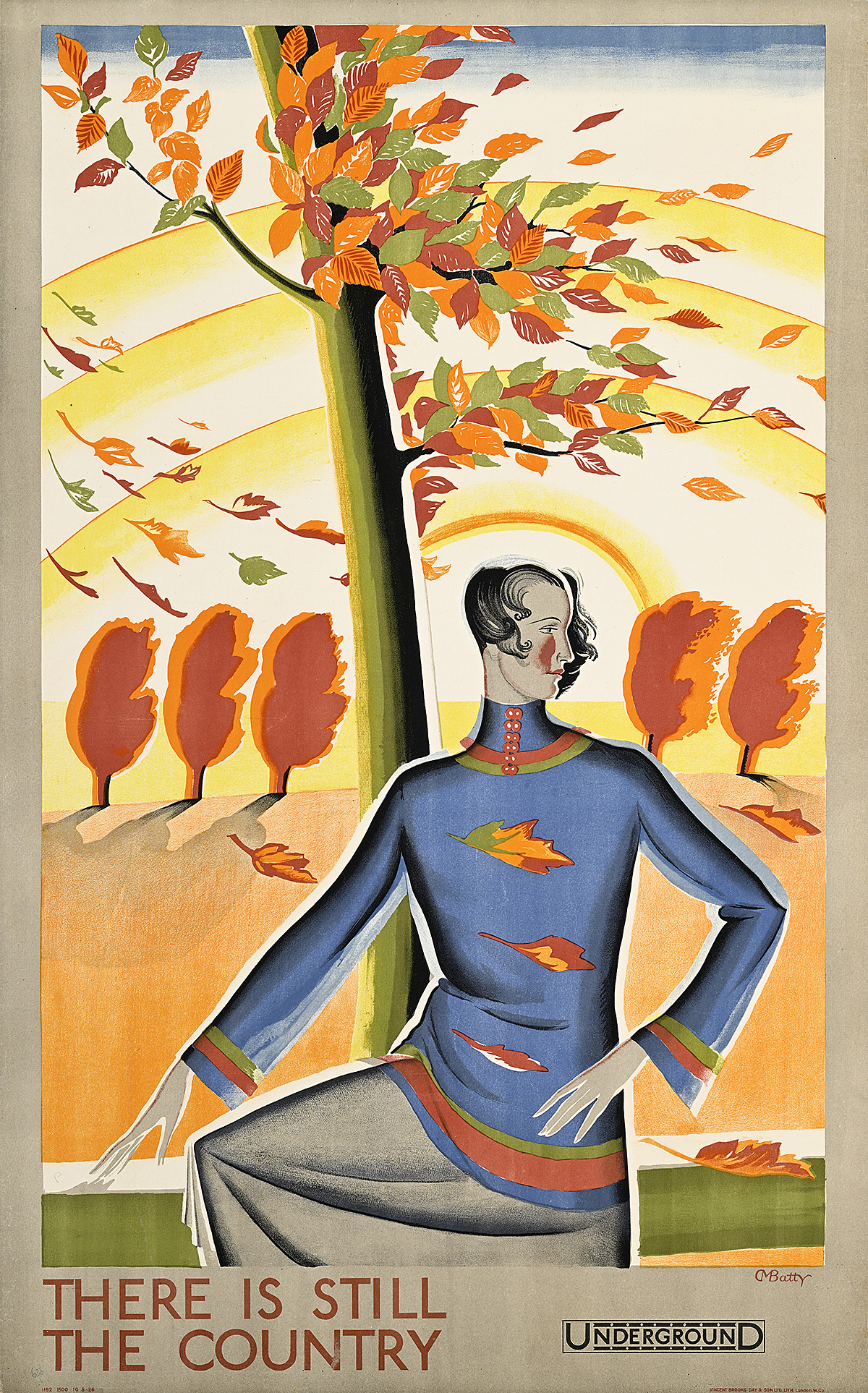

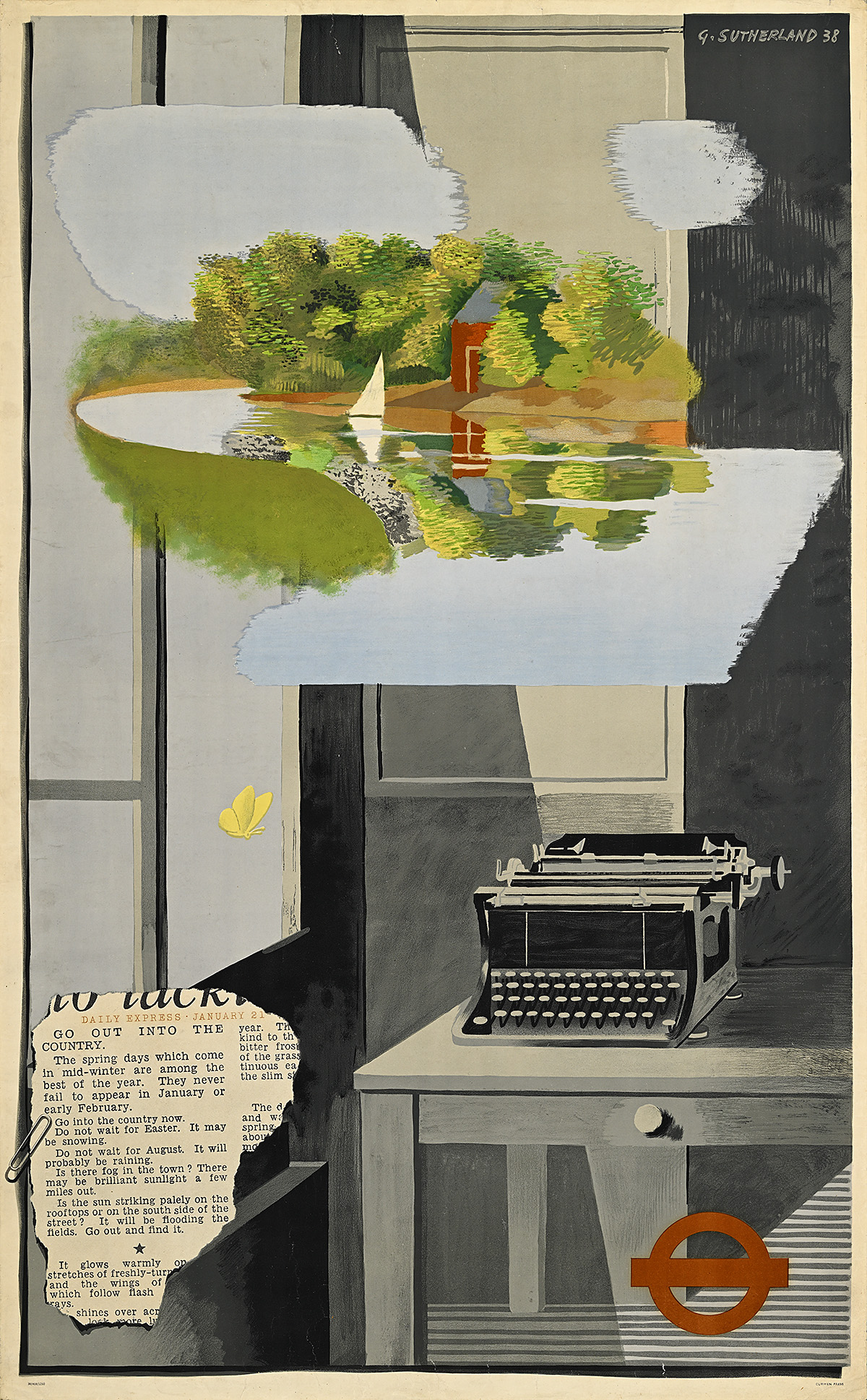

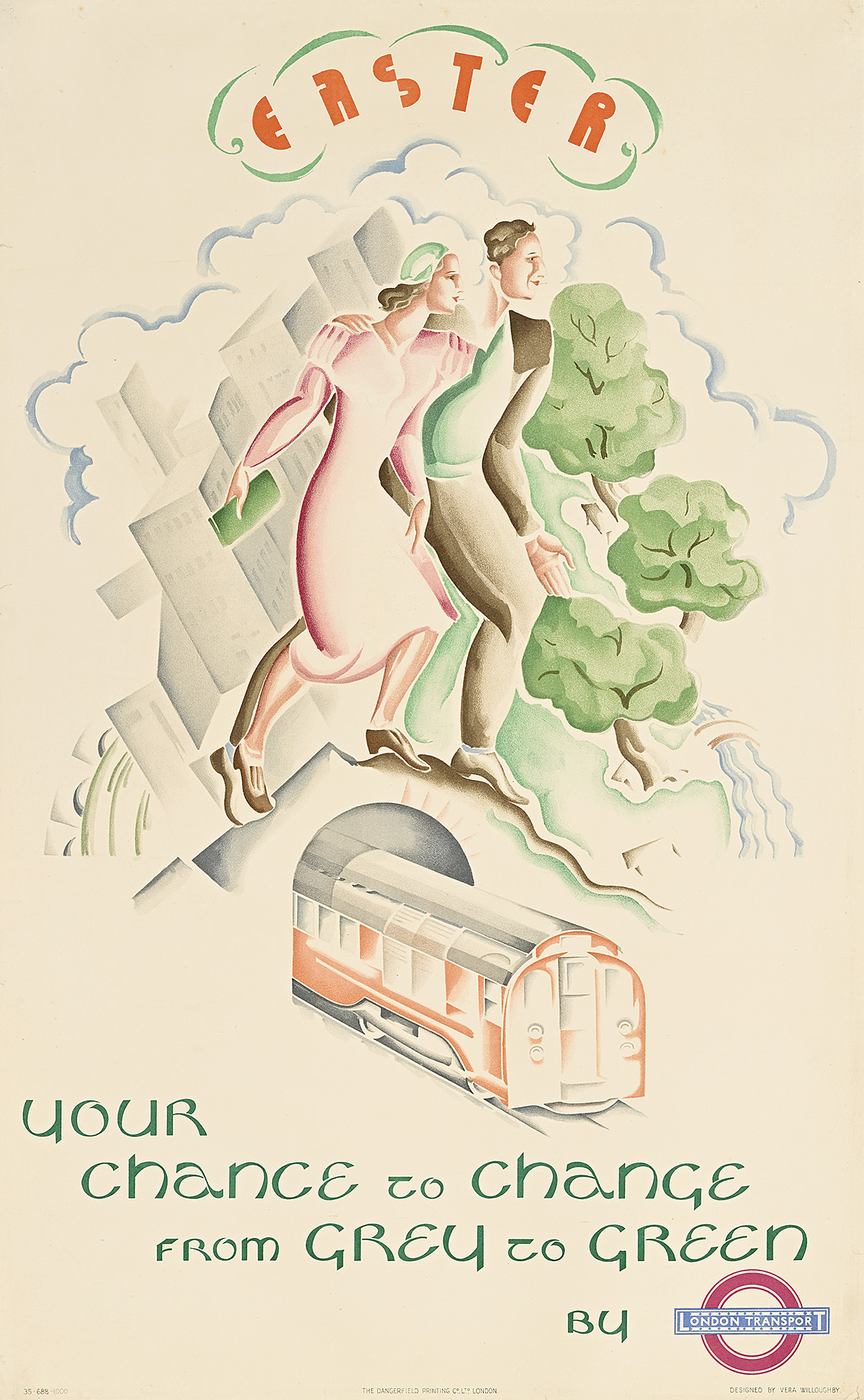

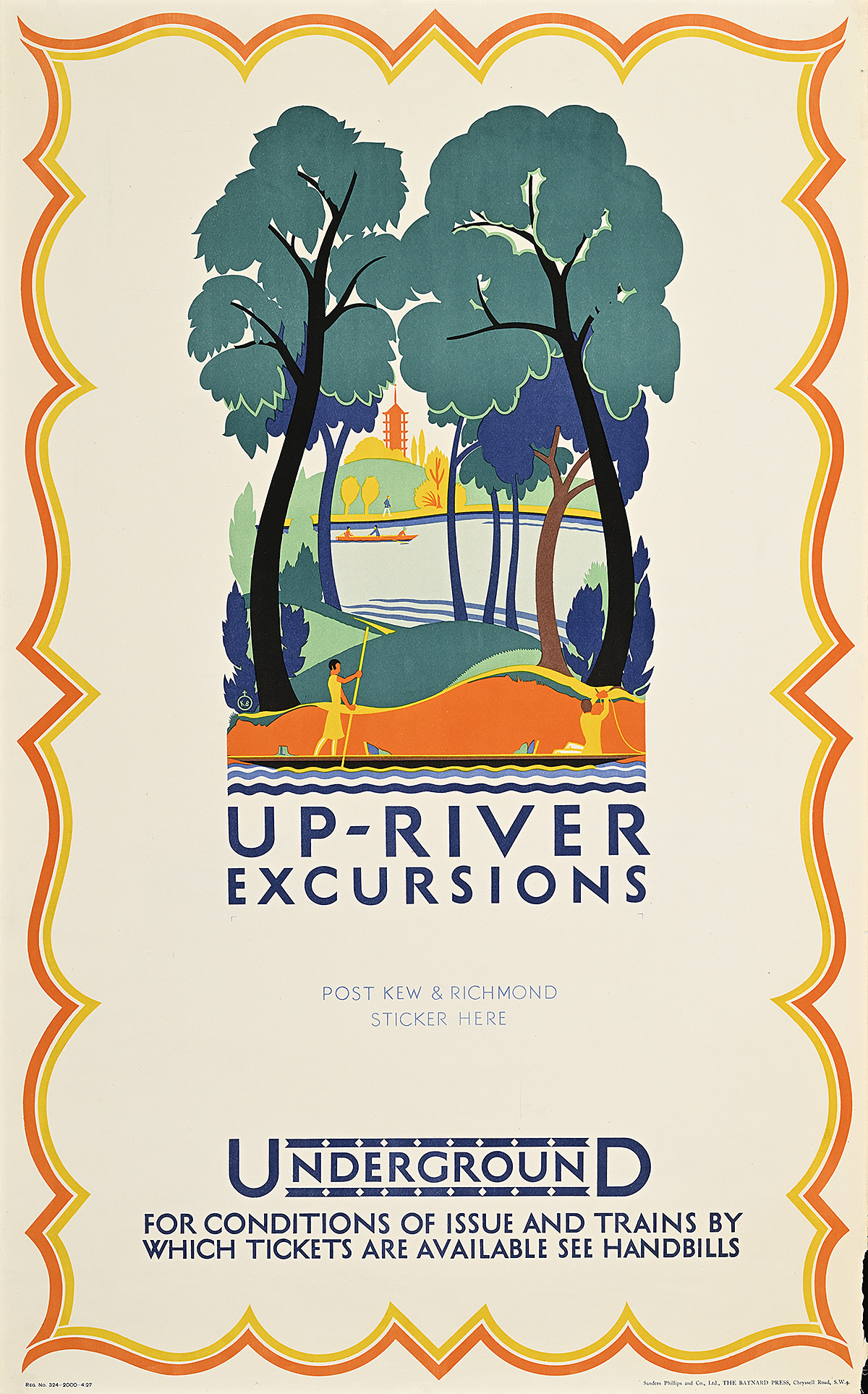

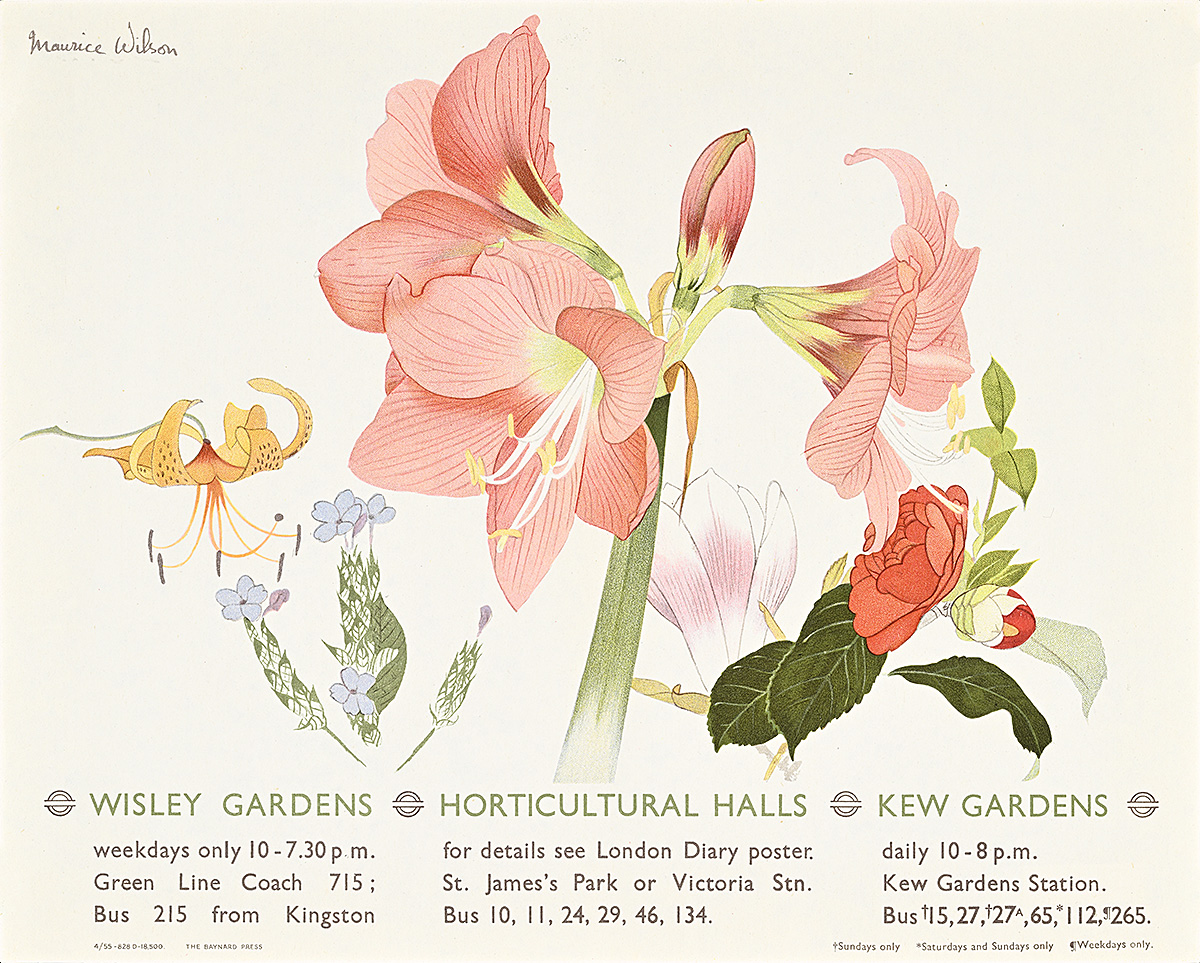

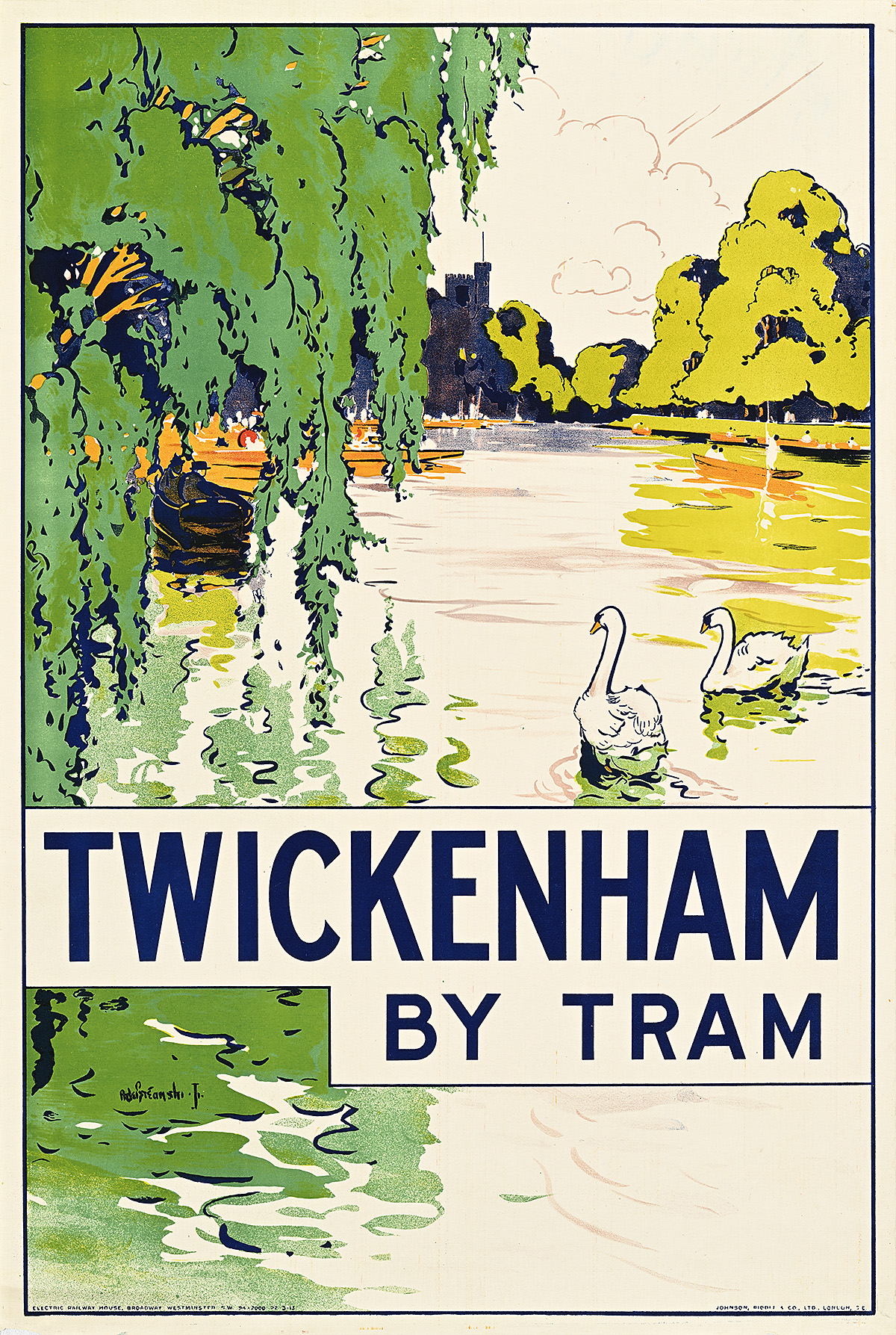

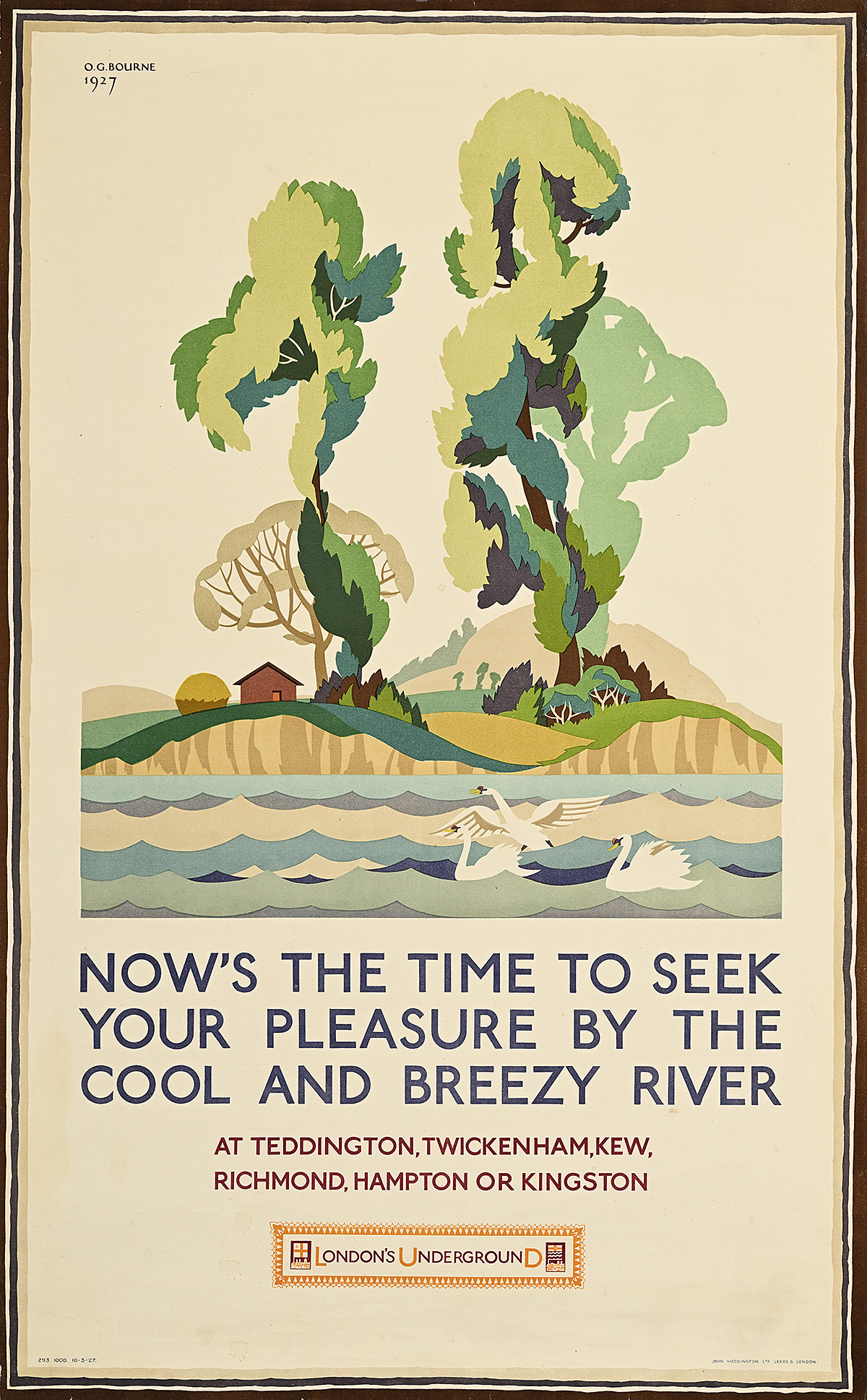

The majority of the works in this exhibition date from the golden age of London Passenger Transport Board posters—broadly speaking the 1920s and ’30s—when many artists were commissioned to produce designs, primarily for the London Underground (colloquially known as the Tube) and its various connecting networks of tram and bus lines. Frank Pick, the managing director of the Transport Board, shaped the network’s unified approach to industrial design, commissioning everything from award-winning buildings and railway vehicles to strikingly modern posters. In this post-World War I era, the overarching concept behind the poster campaigns was to encourage off-peak travel across the wider network through eye-catching, attractive designs, thus driving up revenues for underused lines that were not reaching anticipated profit targets.

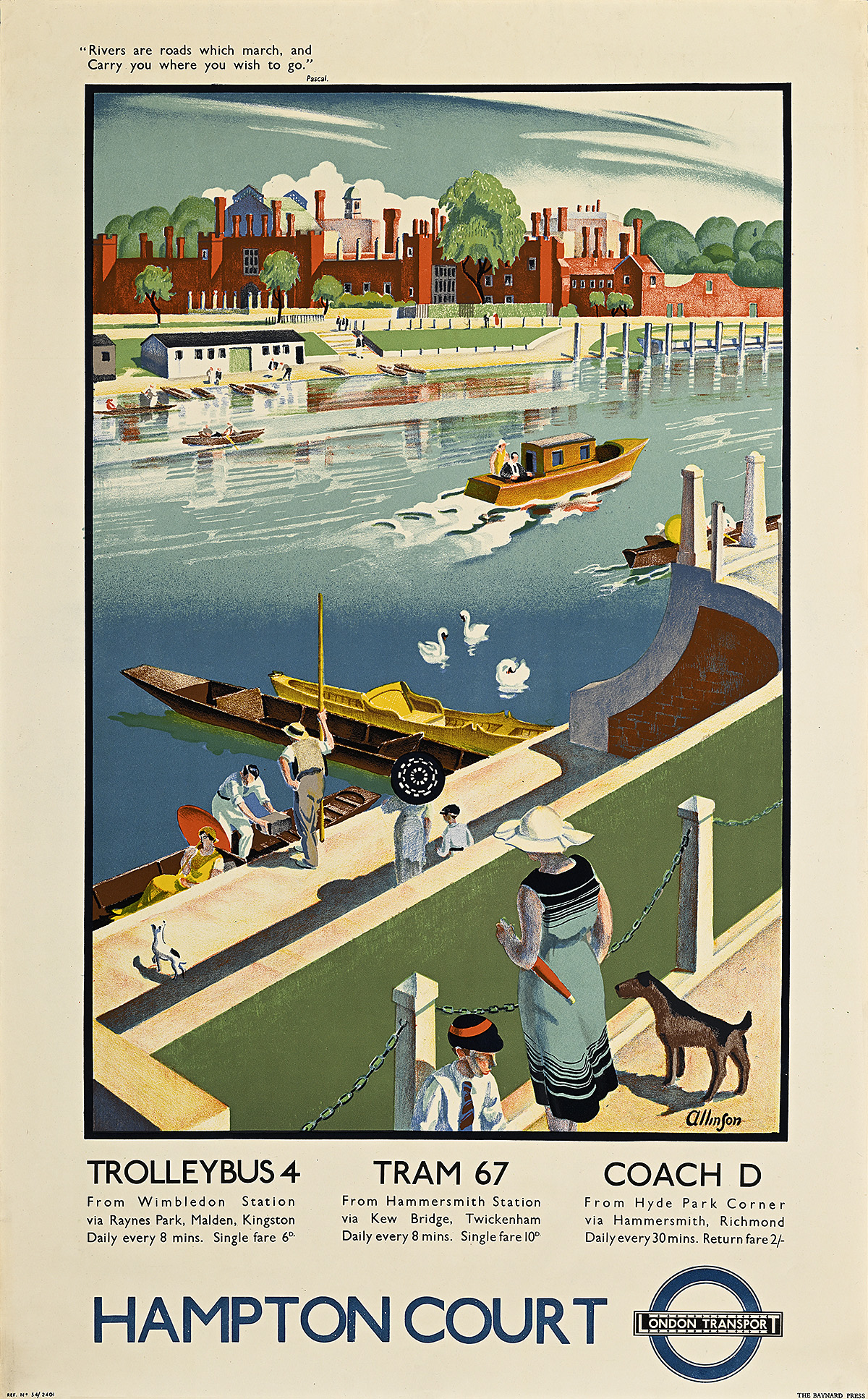

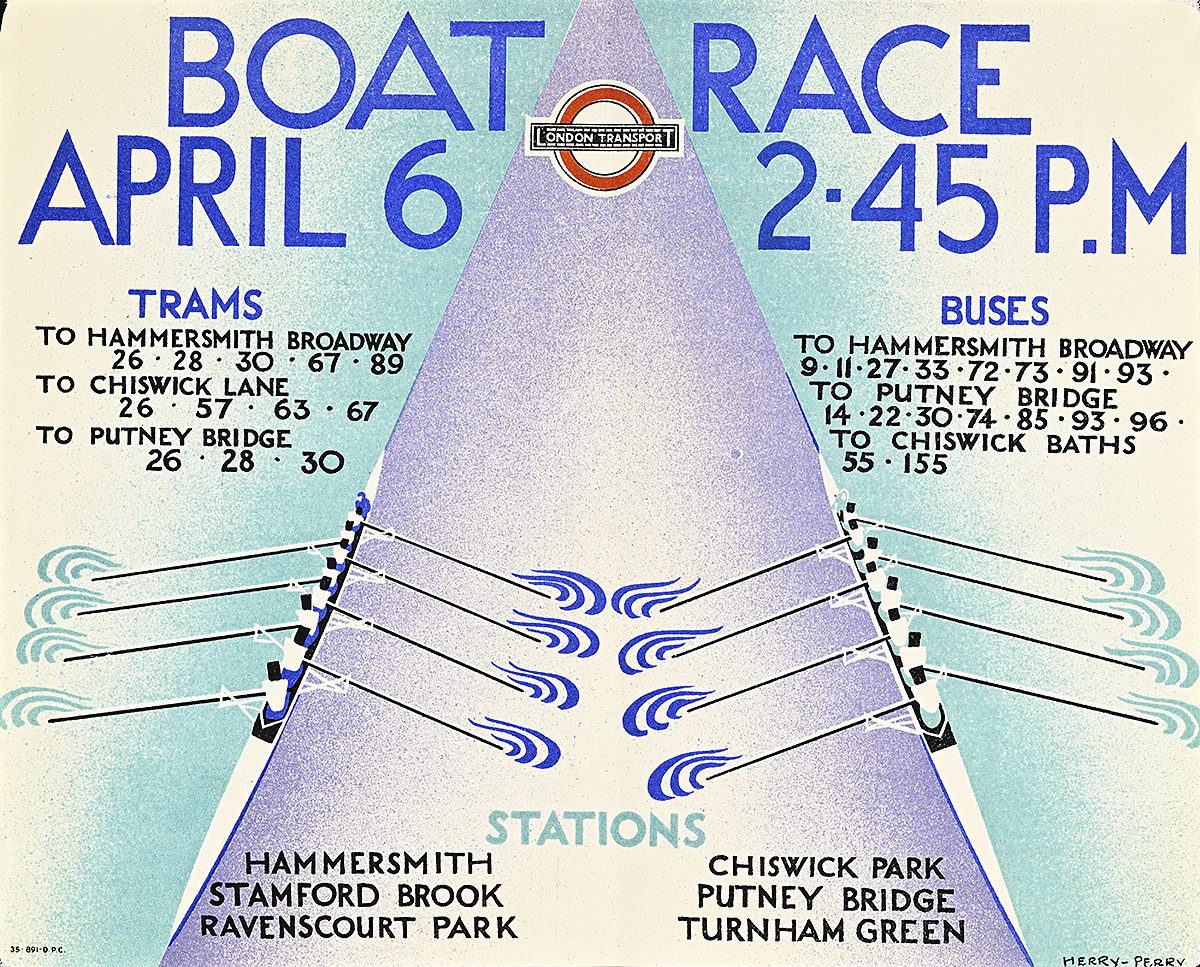

Most of these posters did not advertise the train lines themselves but focused on images of pastoral and other unspoiled destinations suitable for weekend day trips such as historic country houses and beaches, or on sporting events like rowing races, all on the outer reaches of the Tube lines. At the time, this kind of aspirational advertising was rare, but both enthusiasts and critics of the poster campaigns labeled them as effective propaganda.

By representing a variety of destinations, these campaigns also emphasized the breadth of the network. Although popularly thought of as an urban rail system, by 1910, the Tube had branches that stretched via the 60-mile-long District Line to the greenery of Wimbledon and the riverside of Richmond, via the 42-mile-long Metropolitan Line to bucolic Buckinghamshire, and via the 36-mile-long Northern Line past the vast expanse of Hampstead Heath and beyond to suburban Hertfordshire. By contrast, the longest line on the New York City subway is the 31-mile-long A train, which did not open until 1932.

The designers of these vividly colored posters frequently juxtaposed the inherent grayness of inner-city London with images of vibrant locations available just a short Tube ride away. There was a certain reality to this, however: before the Clean Air Act was ratified in 1956, mandating that only smokeless fuels could be burned in London, the city was known to many as “The Smoke” due to the legendary smog that hung over it like a putrid blanket. Ironically, one of the most famous Tube posters—Power (1931) by Edward McKnight Kauffer—features Lots Road Power Station, the main provider of electricity to the Tube, proudly belching dark clouds produced by the 700 tons of coal it burned each day. The Thames, the main river that runs through London, was no better. Although frequently depicted in appealing hues, the reality was always very different, and in a 1957 environmental survey the Thames was declared “biologically dead.” The city was extremely polluted, and these posters let riders know that London Transport provided an affordable respite from such unpleasant conditions.

Unless otherwise noted, all posters on display are courtesy of the Hall Art Foundation.

Whenever feasible, Poster House reuses materials from previous shows to drive sustainable practice.

Large text is available at the Info Desk.

Guías con letra grande están disponibles en atención al público.

No beverages beyond this point.