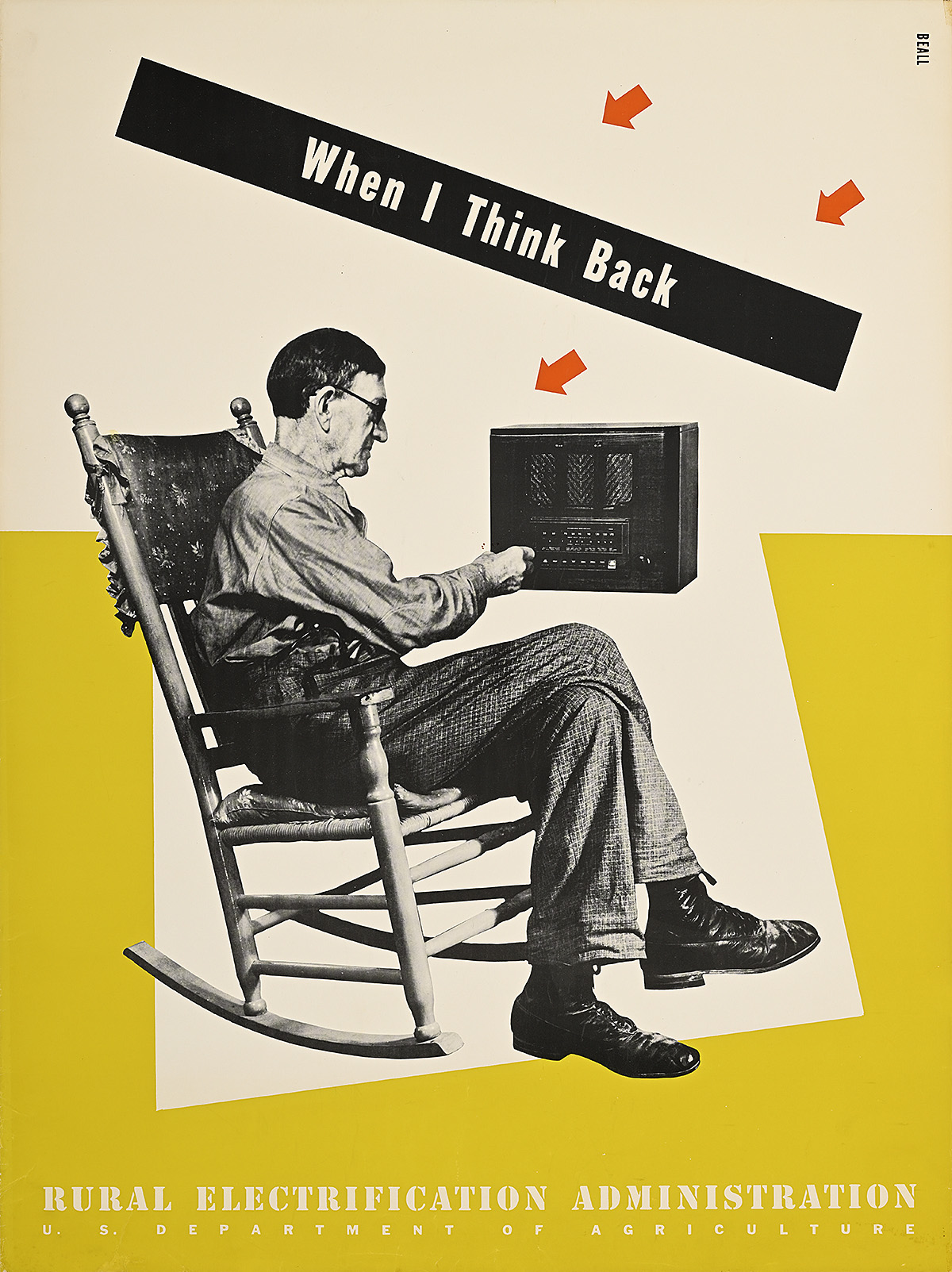

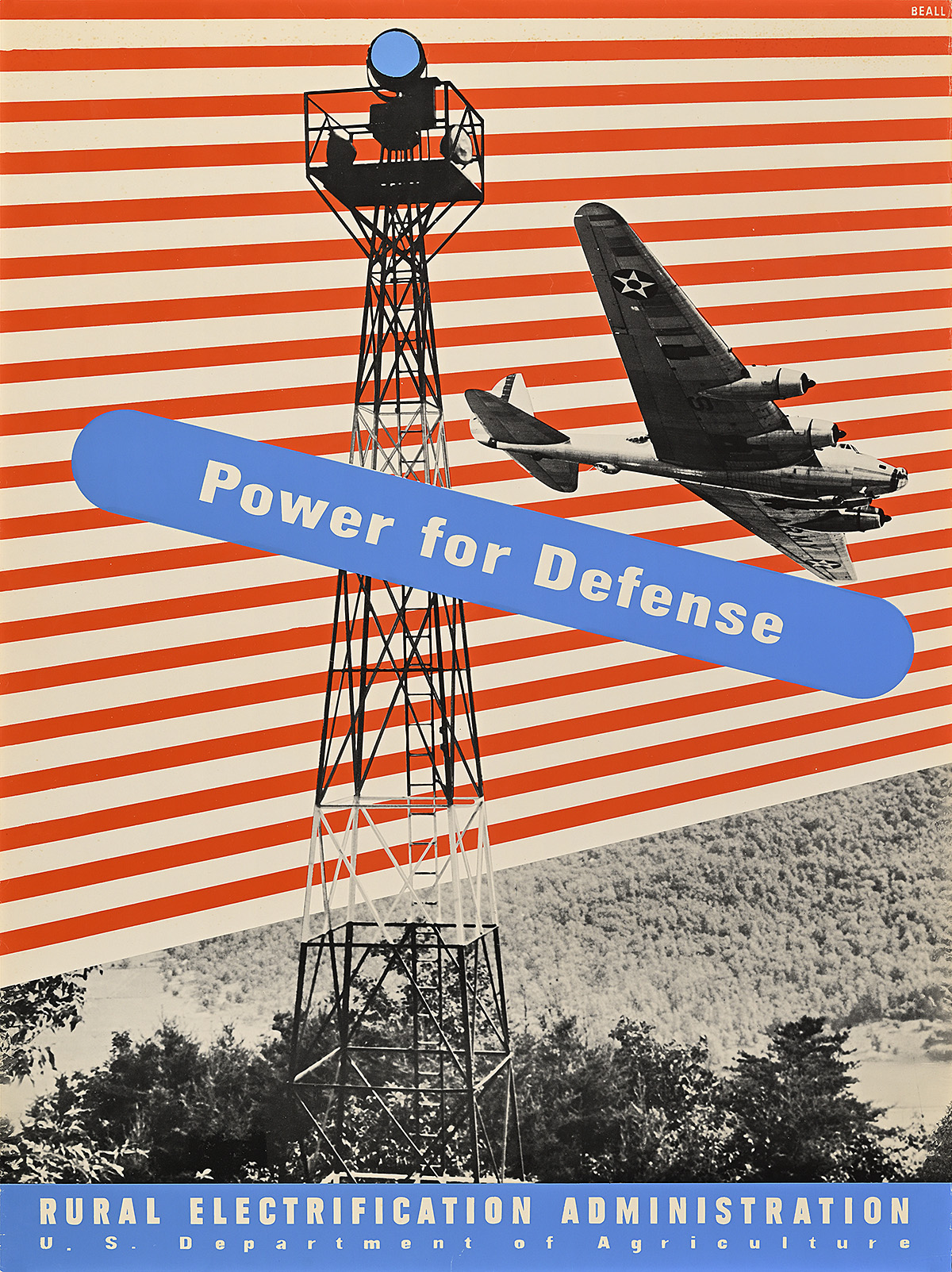

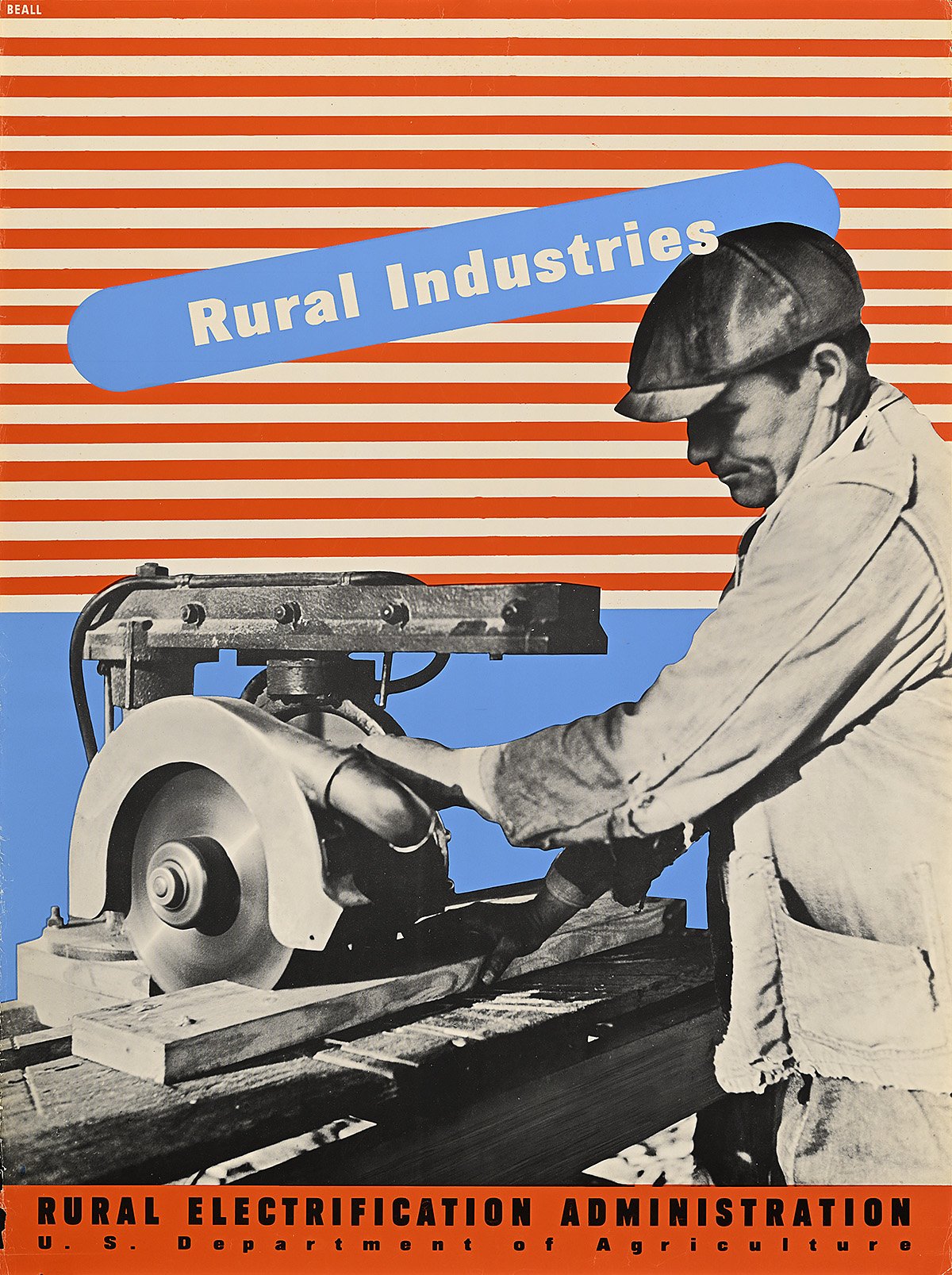

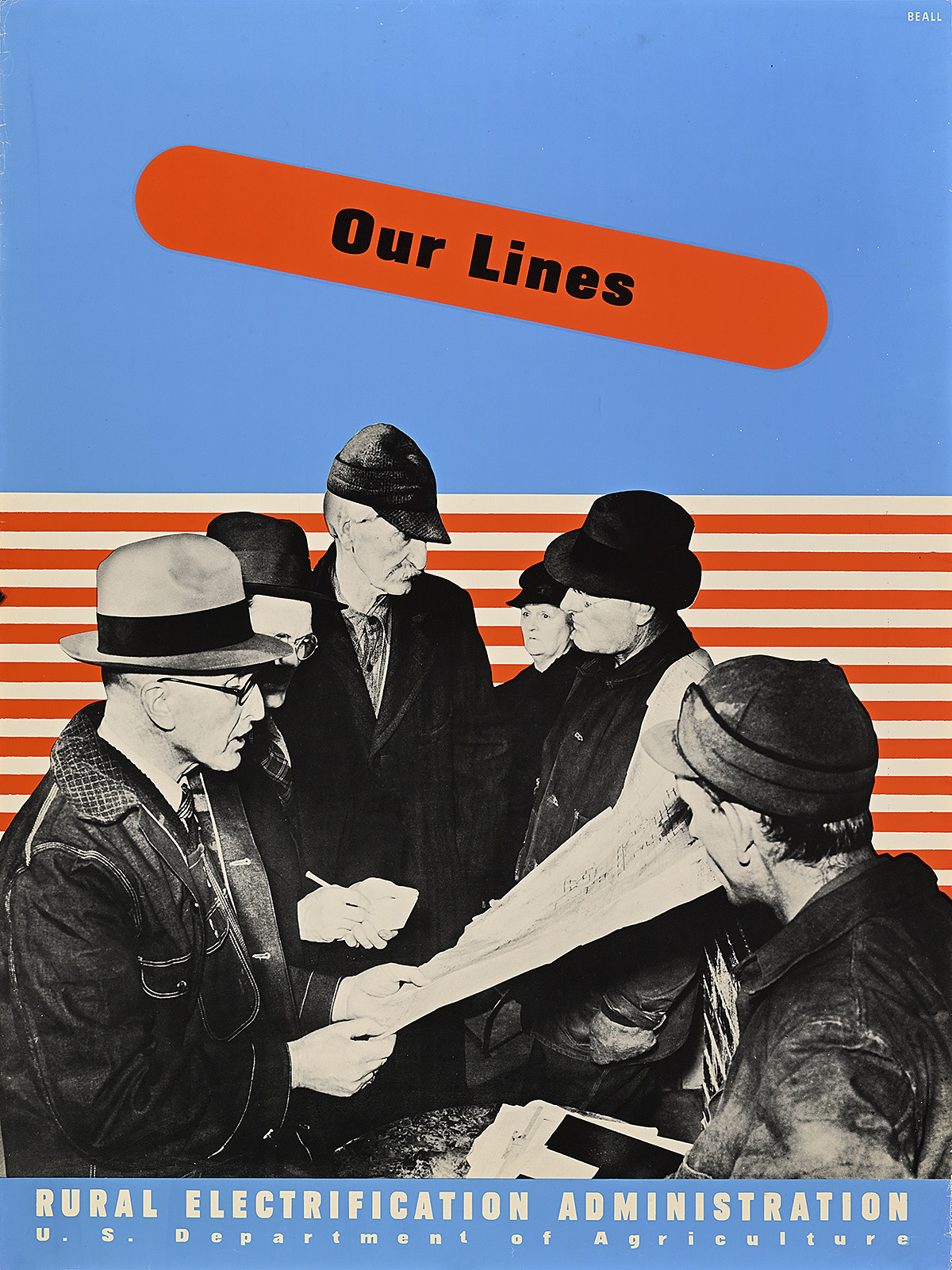

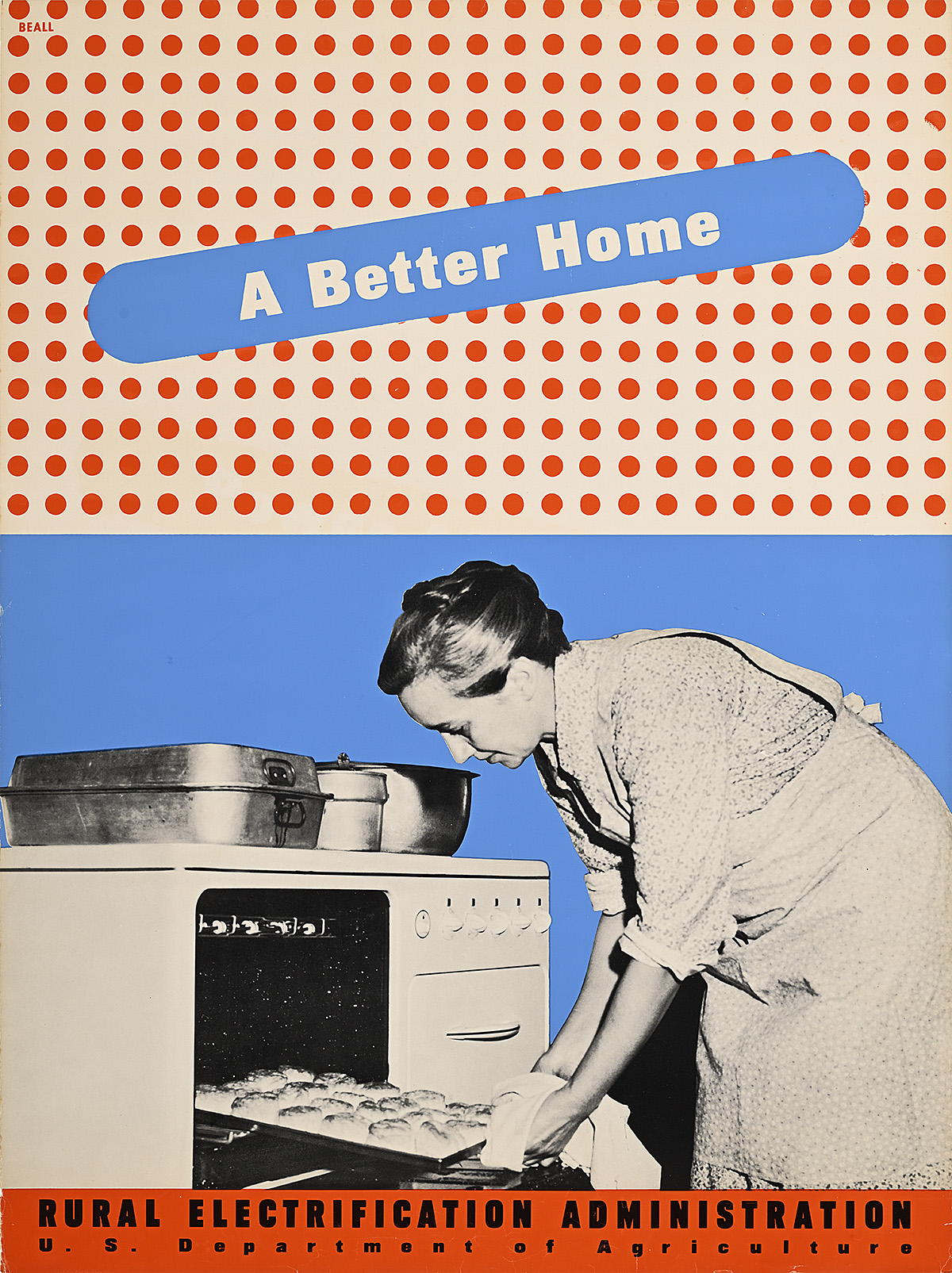

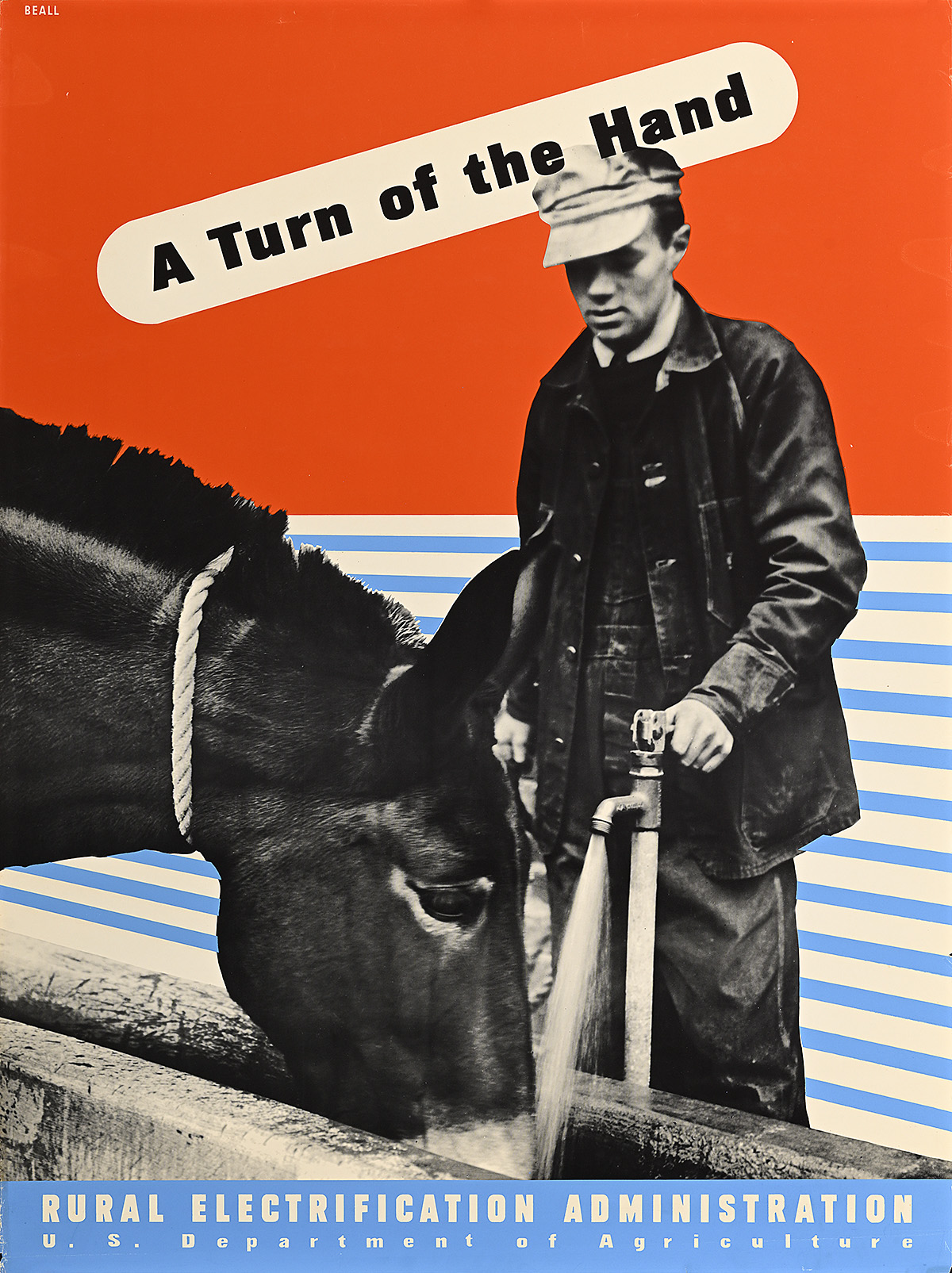

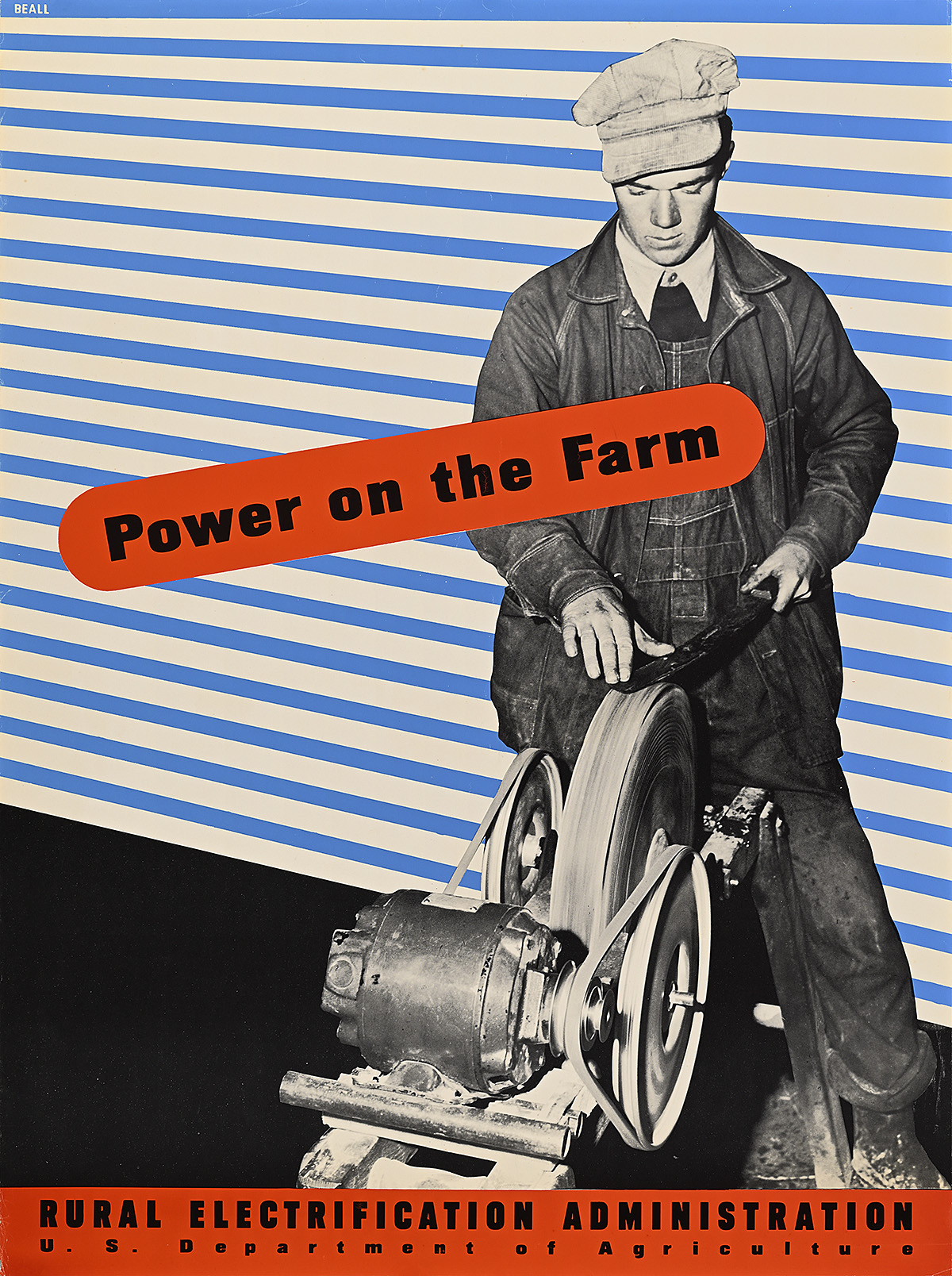

Lester Beall & A New American Identity

Beall’s American Modernism

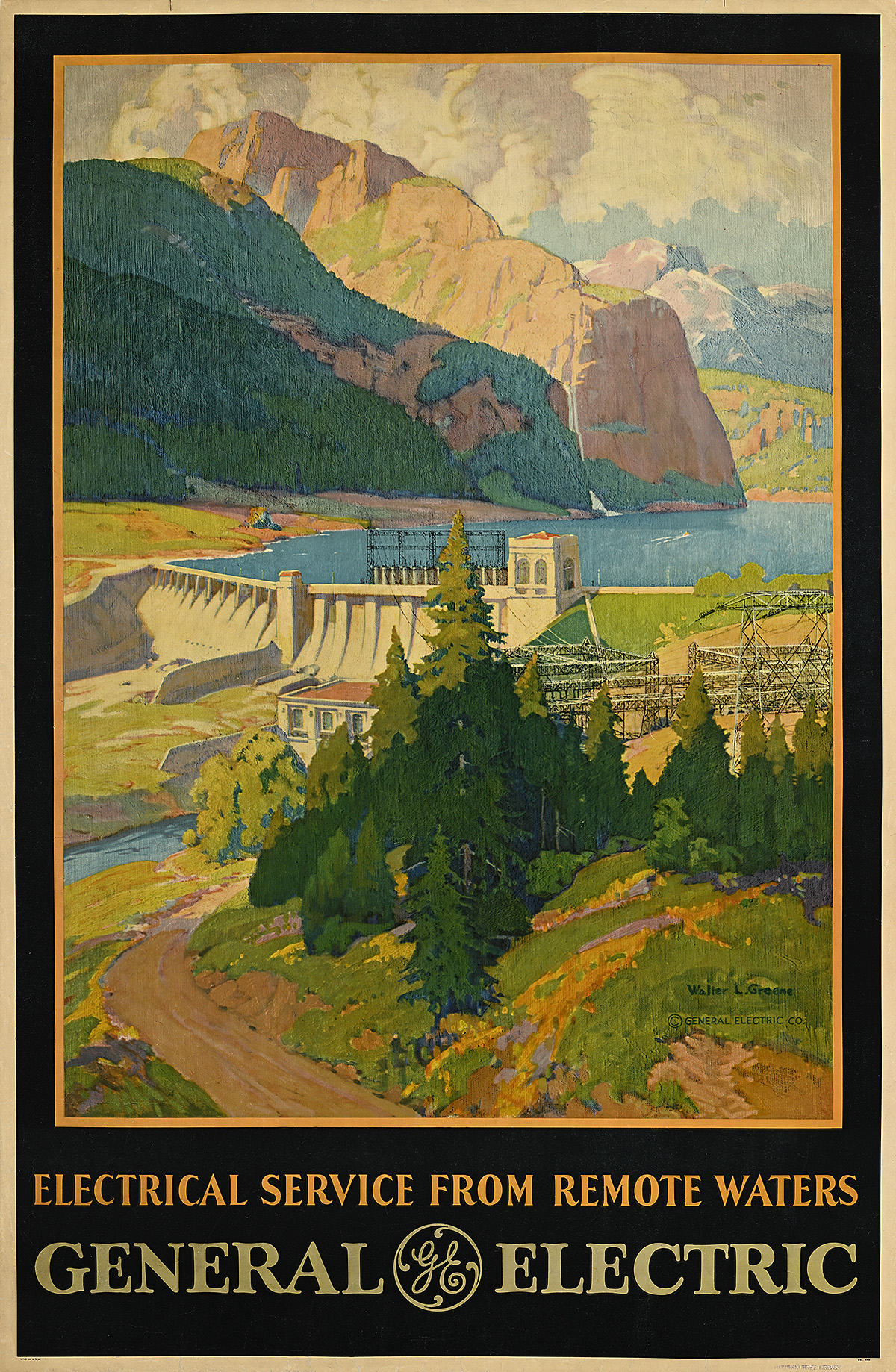

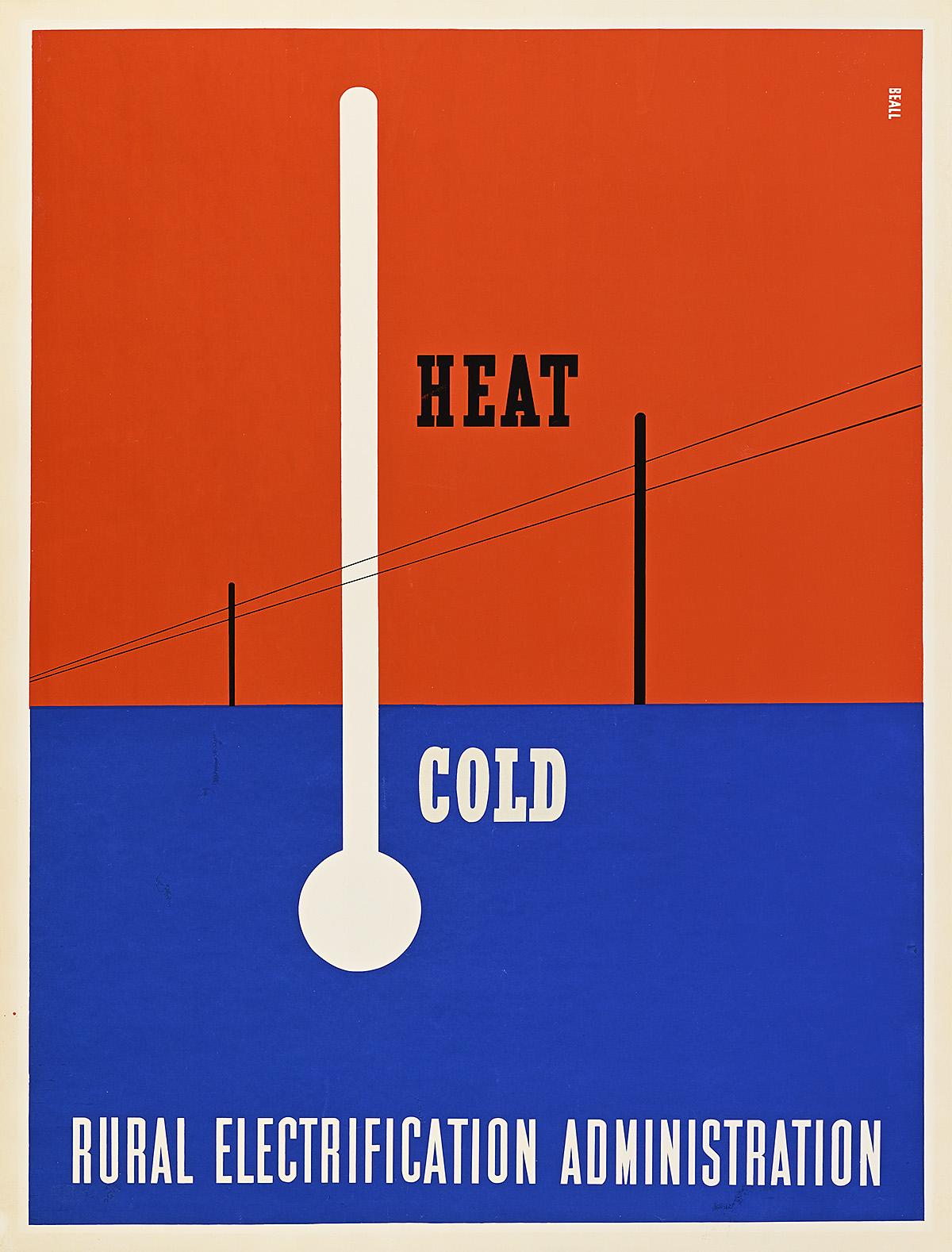

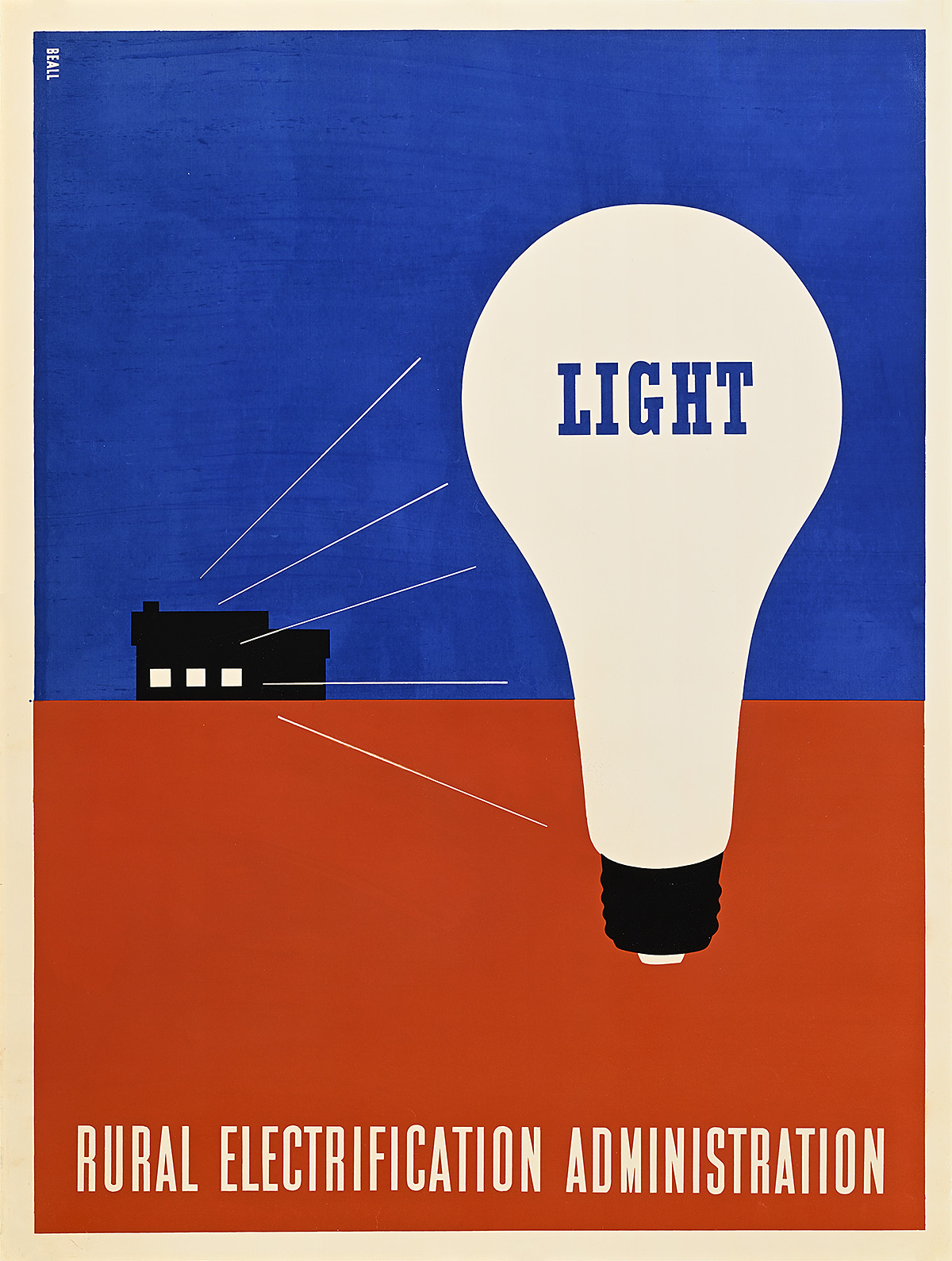

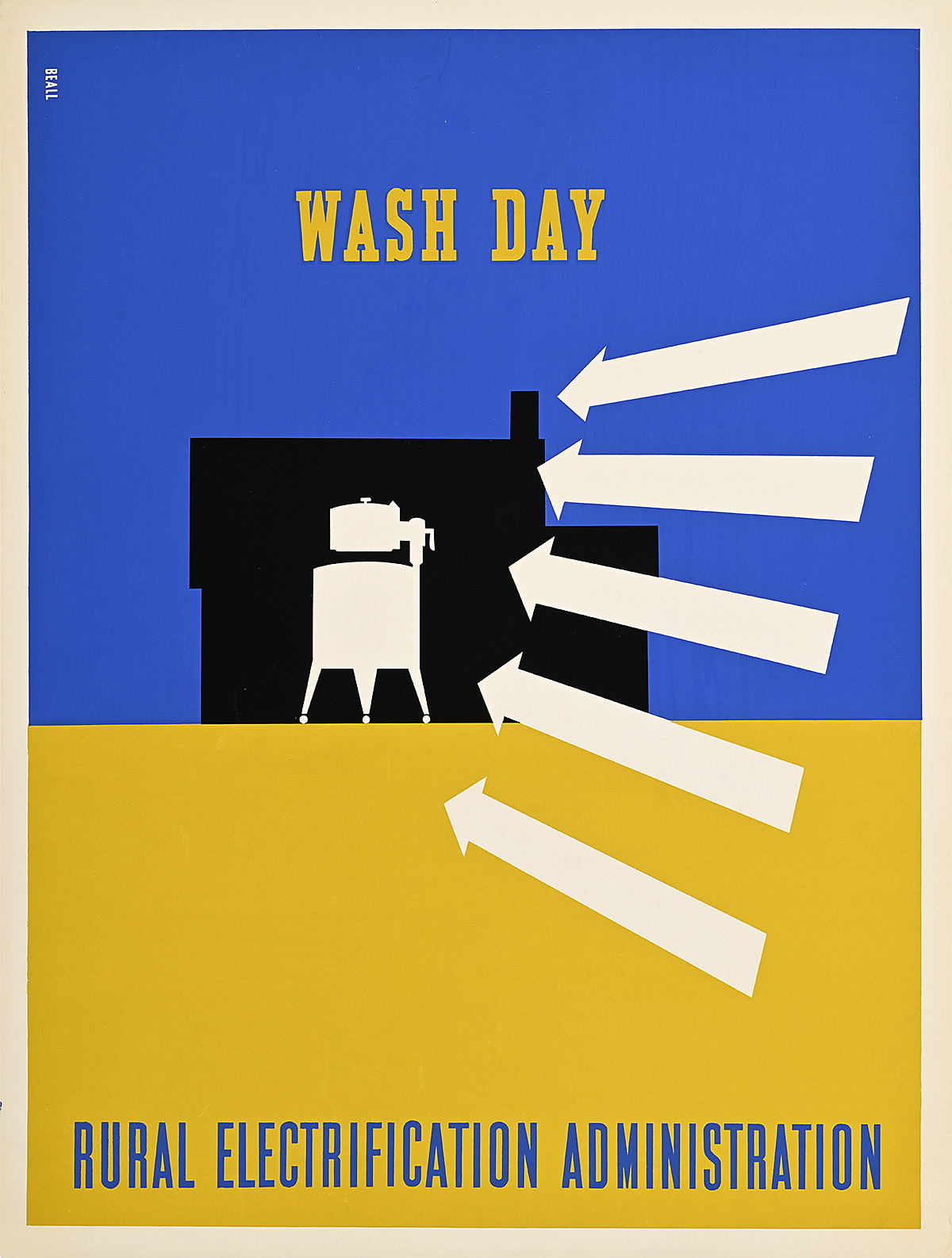

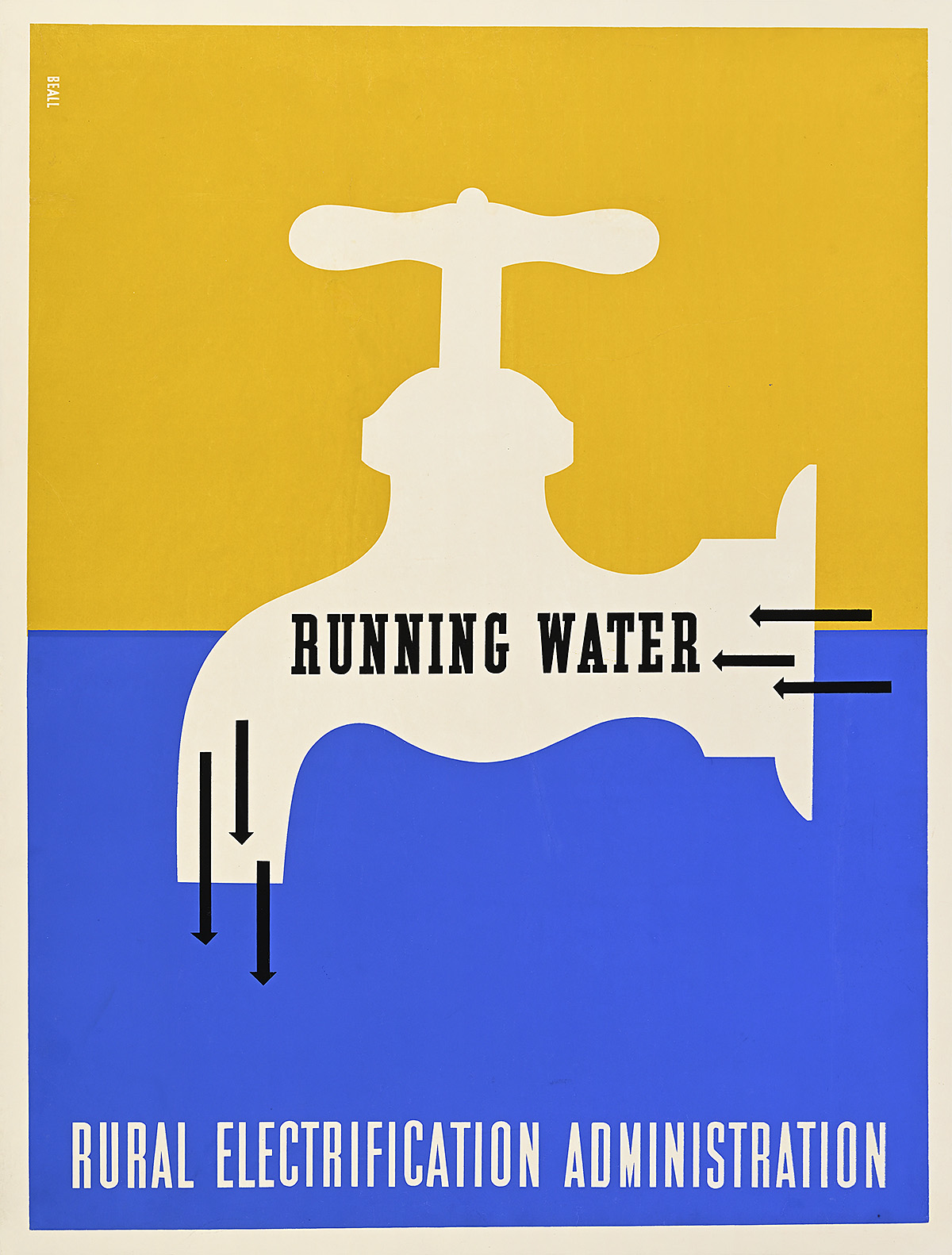

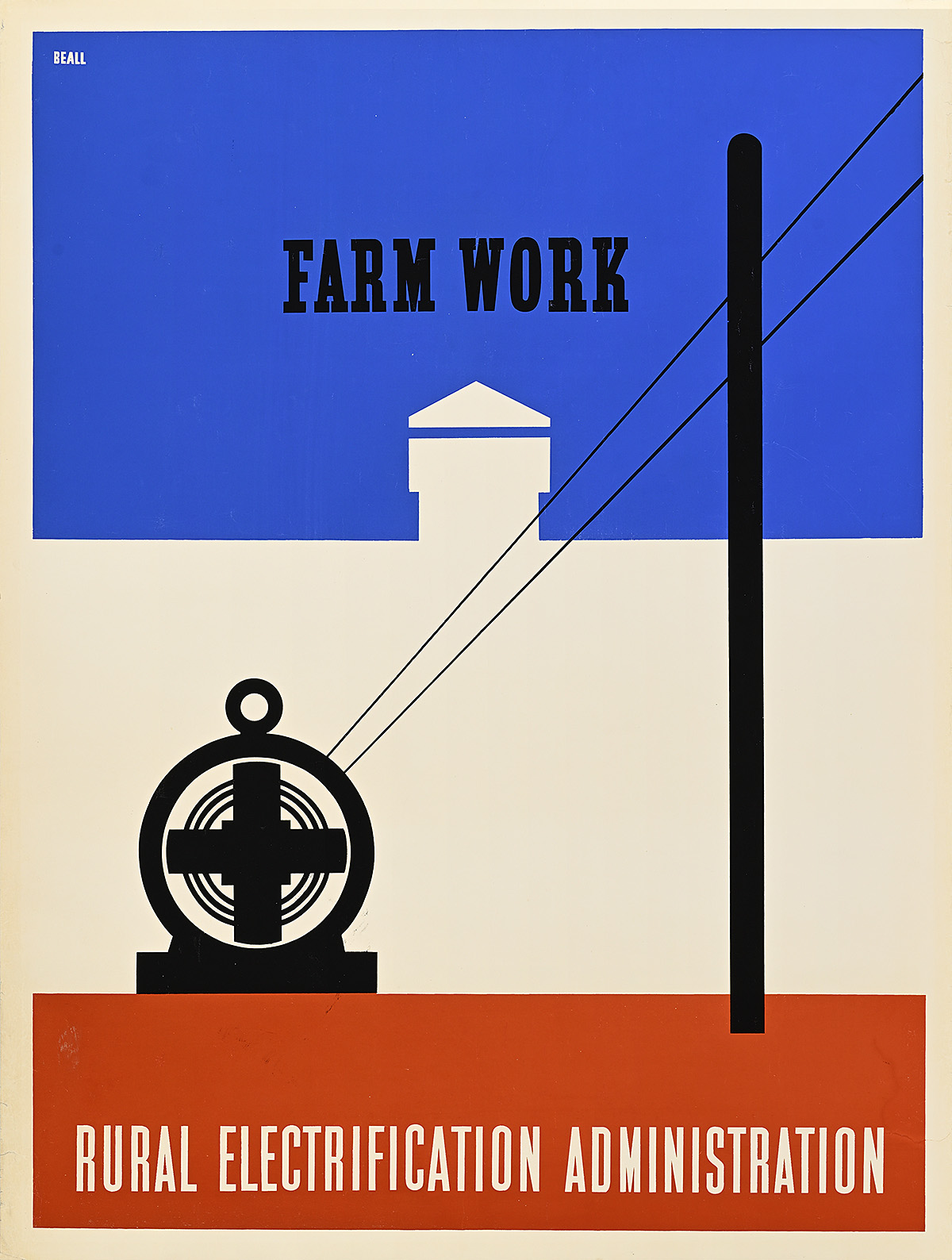

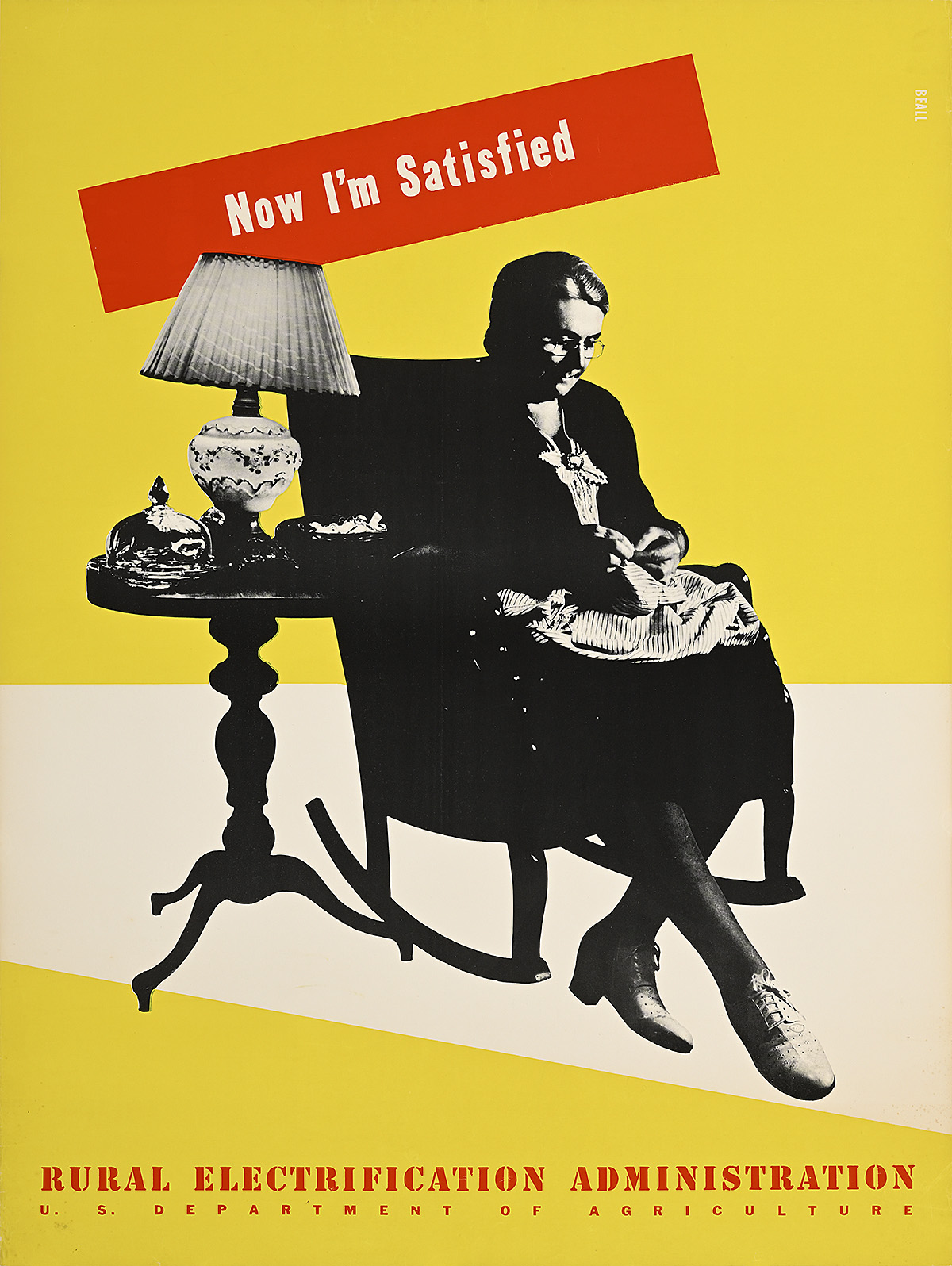

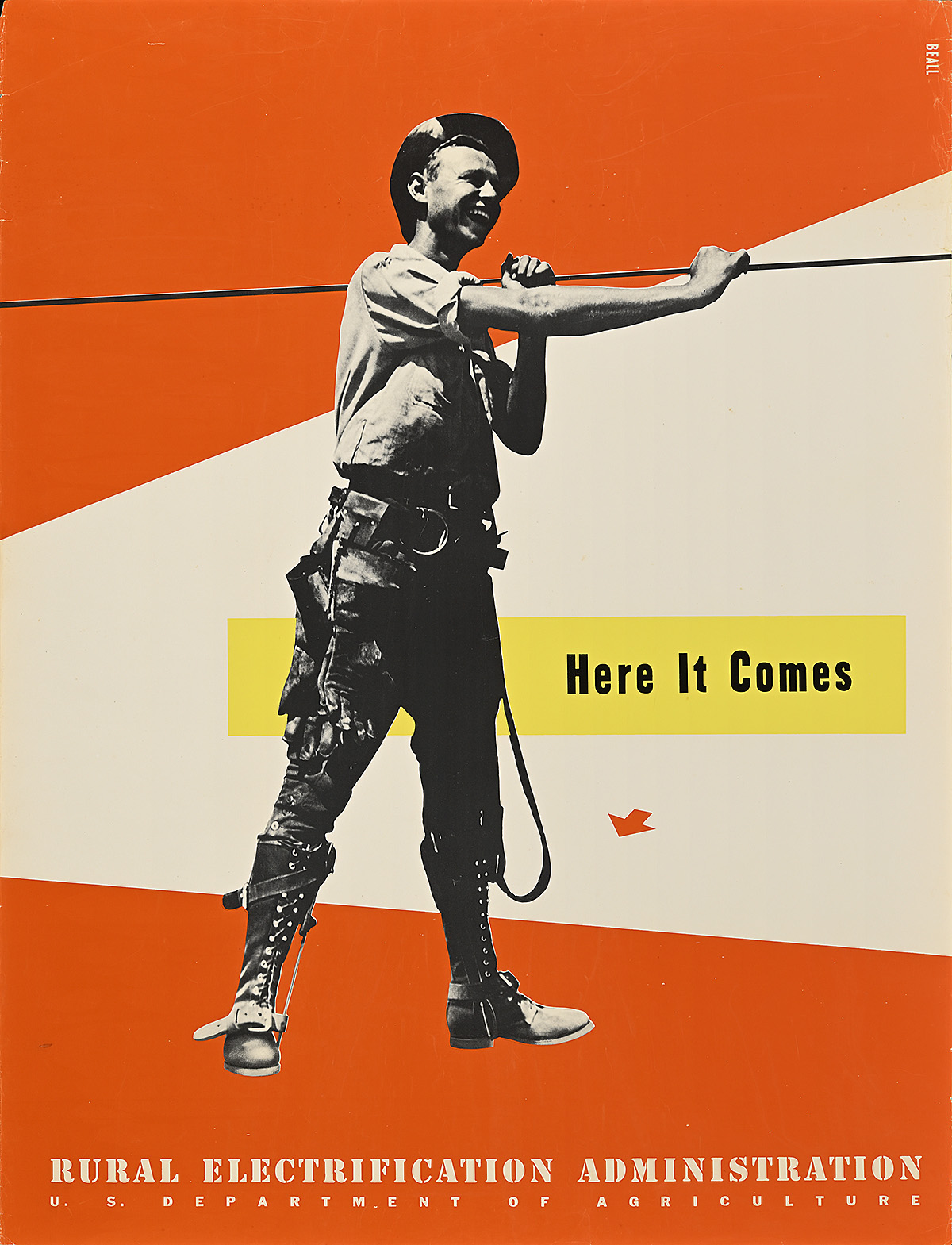

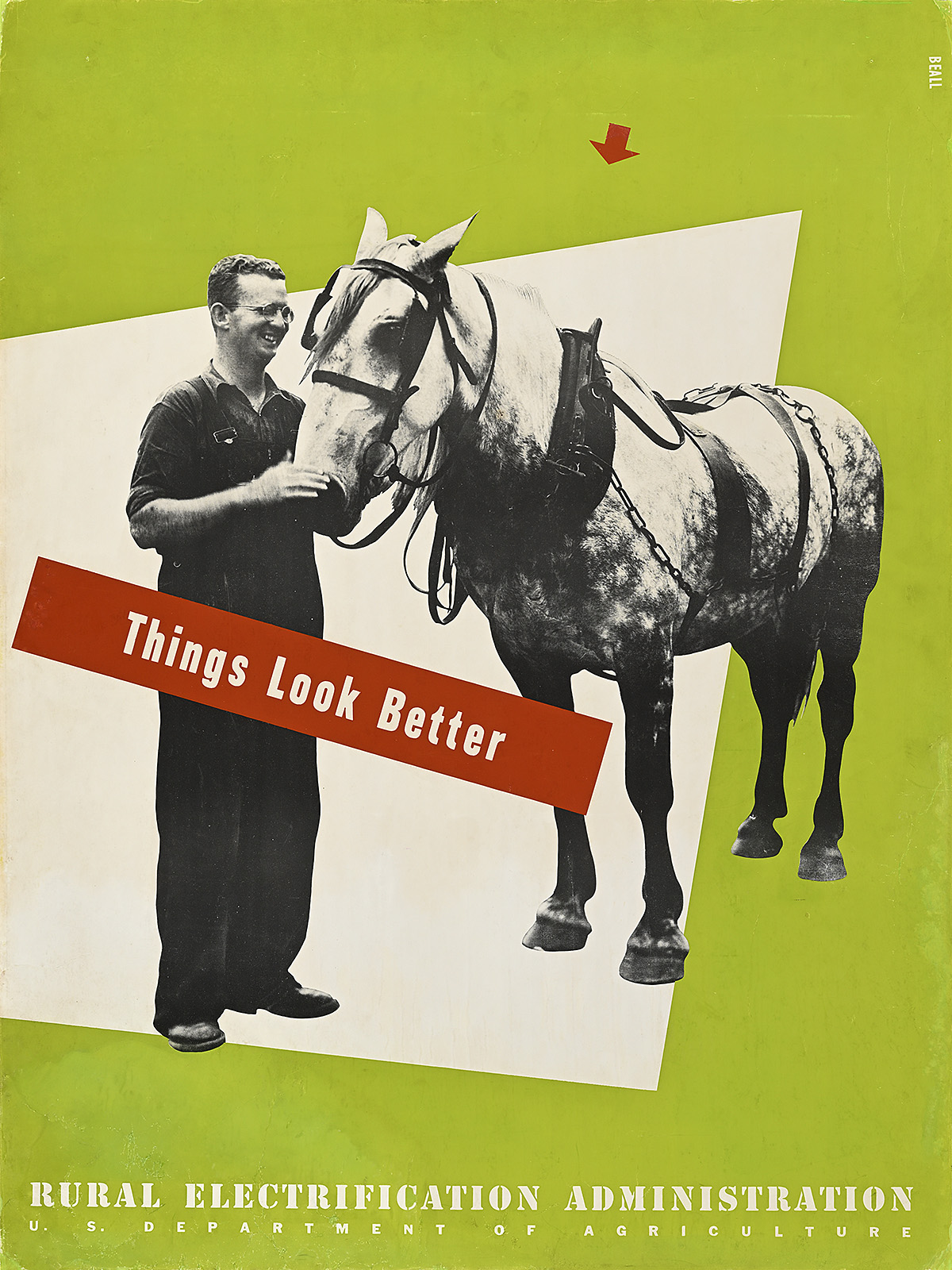

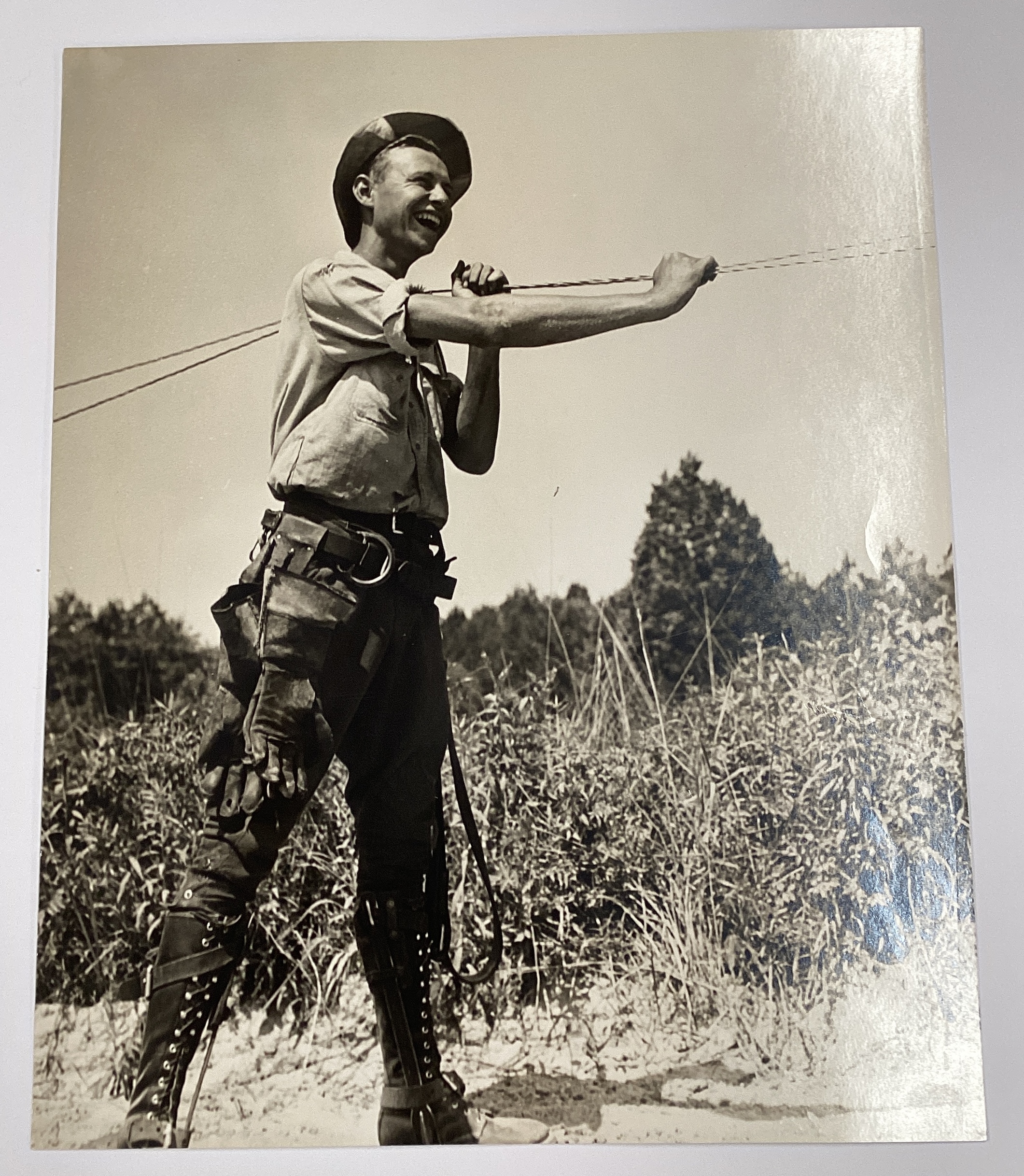

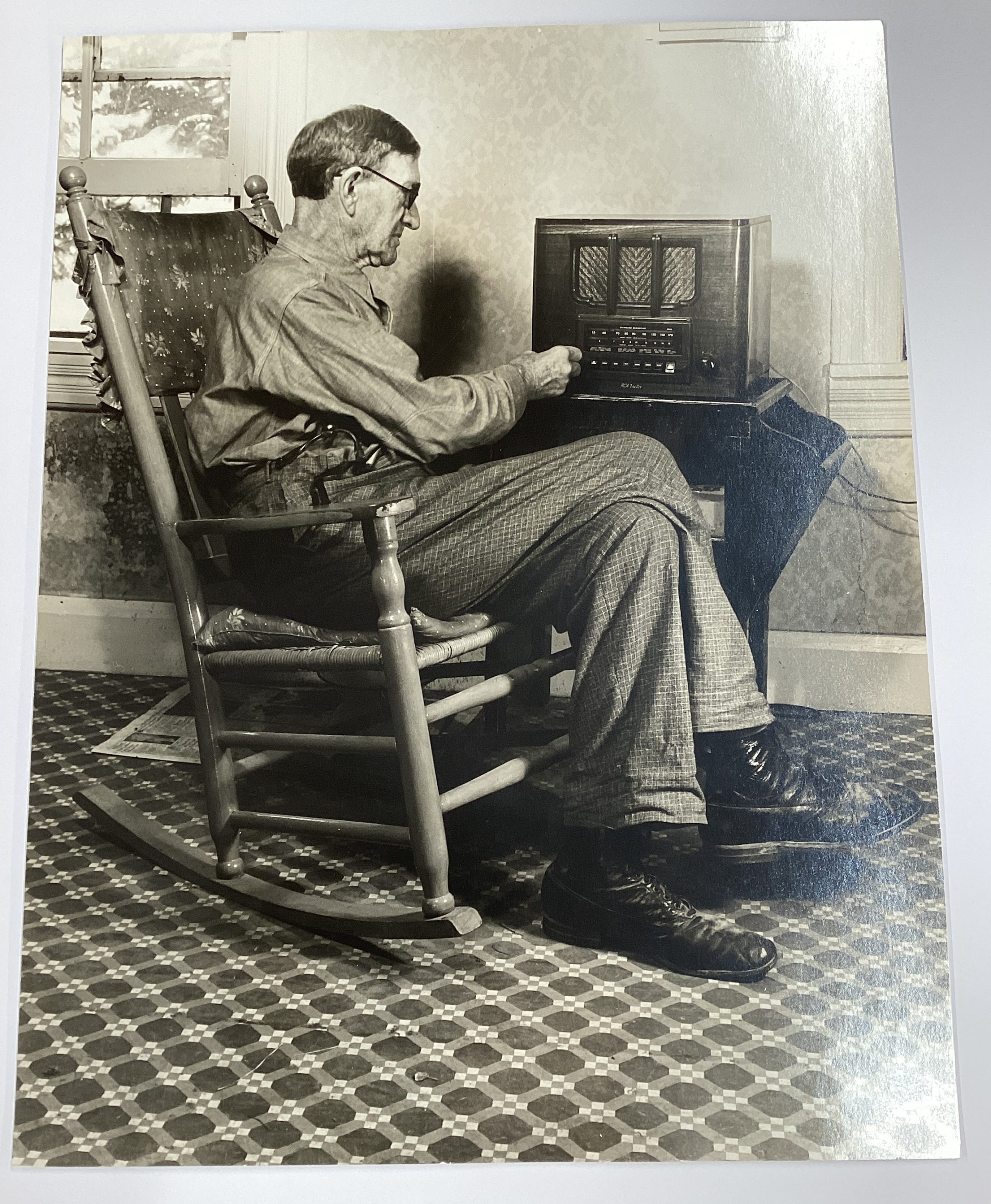

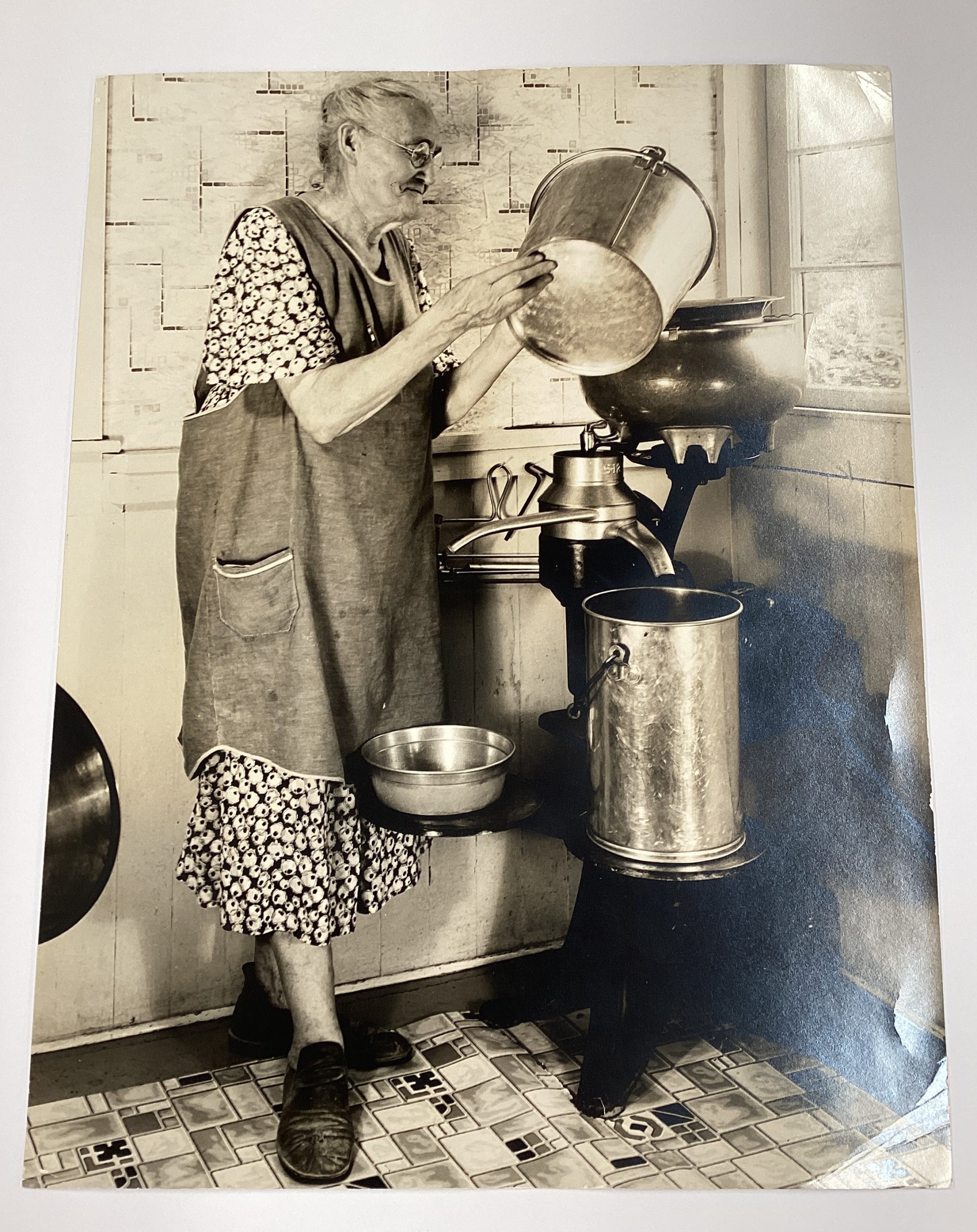

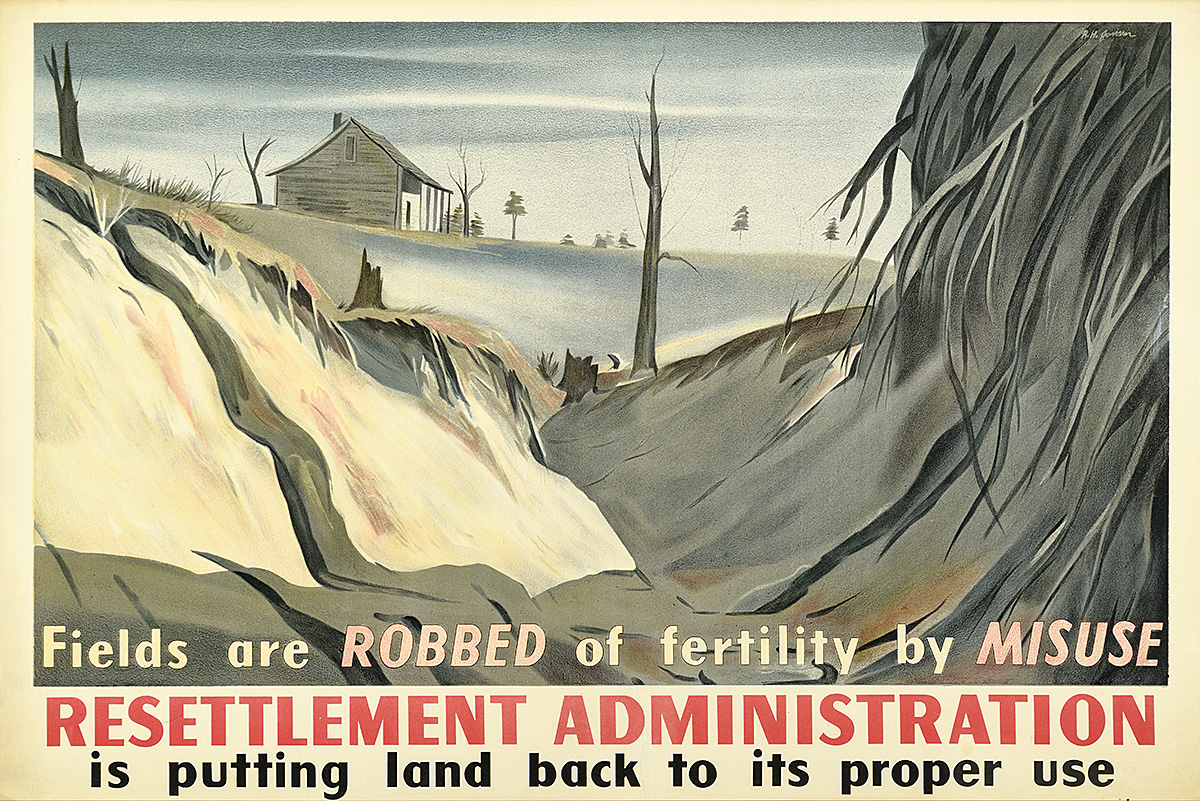

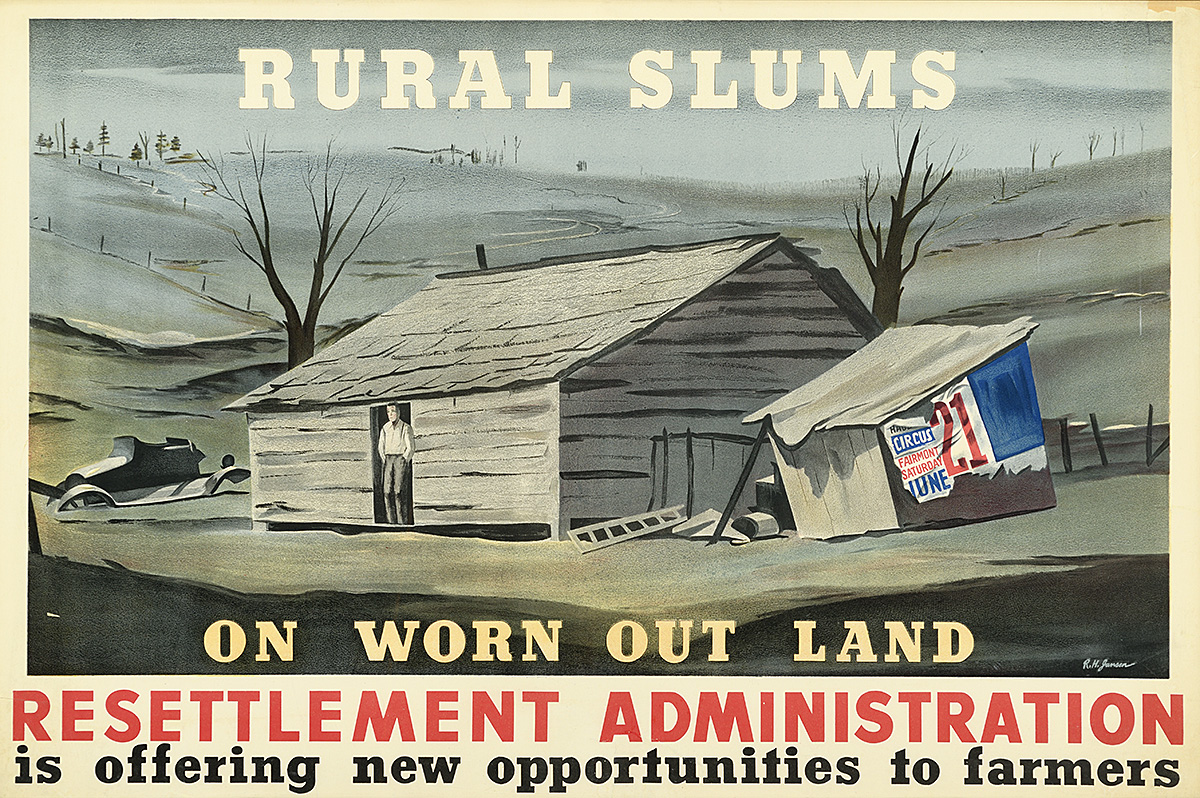

Lester Beall was born into an America on the cusp of broad social revolution as it entered the 20th century. Still tied to the values and slower way of life of the late 1800s, it was a time when only a wealthy minority in major cities could afford or have access to amenities many Europeans already took for granted, including electricity and indoor plumbing. With its sprawling landmass and fragmented population, the United States lagged behind the rest of the Western world—most especially in rural areas—with many of its inhabitants embracing the ideals of self-reliance, small government, and isolationism over modernity and social progress. Beall was all too familiar with such realities of rural life; in his youth, he had spent summers on his family’s midwestern farm. By the time he was in his 20s, the Great Depression would bring into sharp focus the economic and cultural disparities between these two very different versions of America.

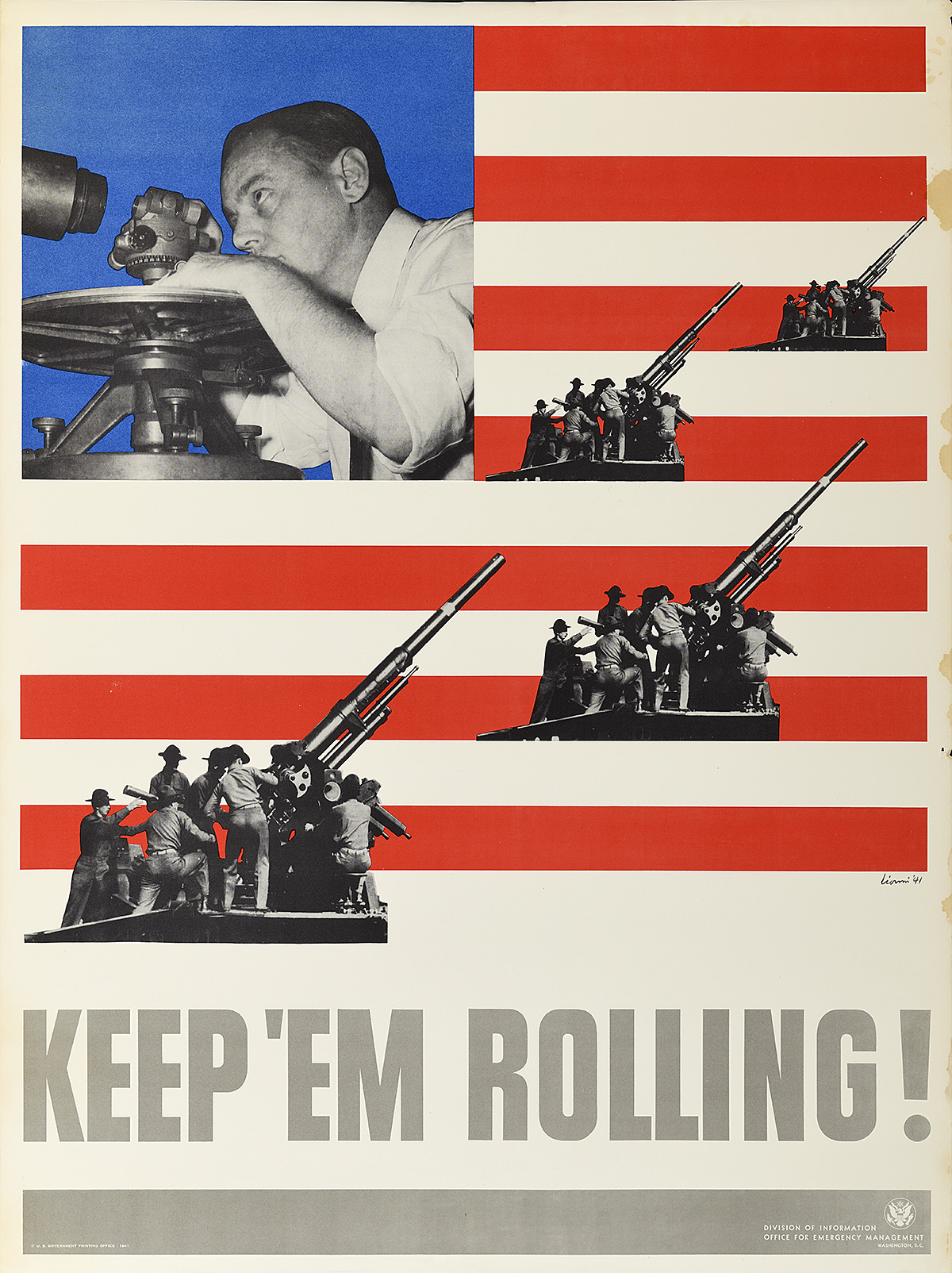

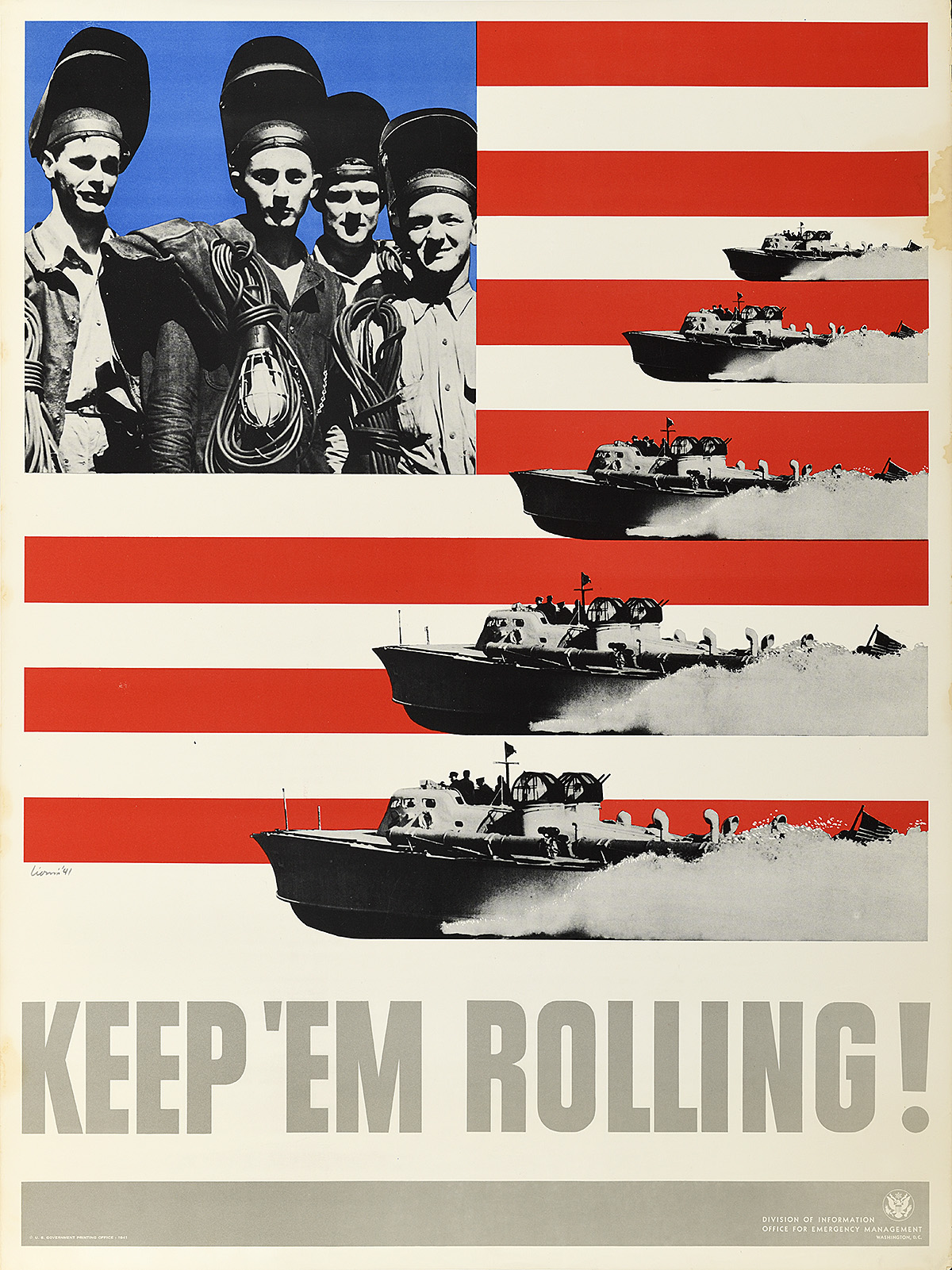

Most American artists drew upon narrative and representational styles popular with U.S. audiences rather than incorporating elements of the avant-garde that were then flourishing in Europe. In terms of poster design, Americans were far more literal-minded and did not respond well to abstraction or other tenets of modernism. As a result, most American posters produced in the early 20th century were illustrational and restrained, reflecting an understated, old-fashioned sensibility.

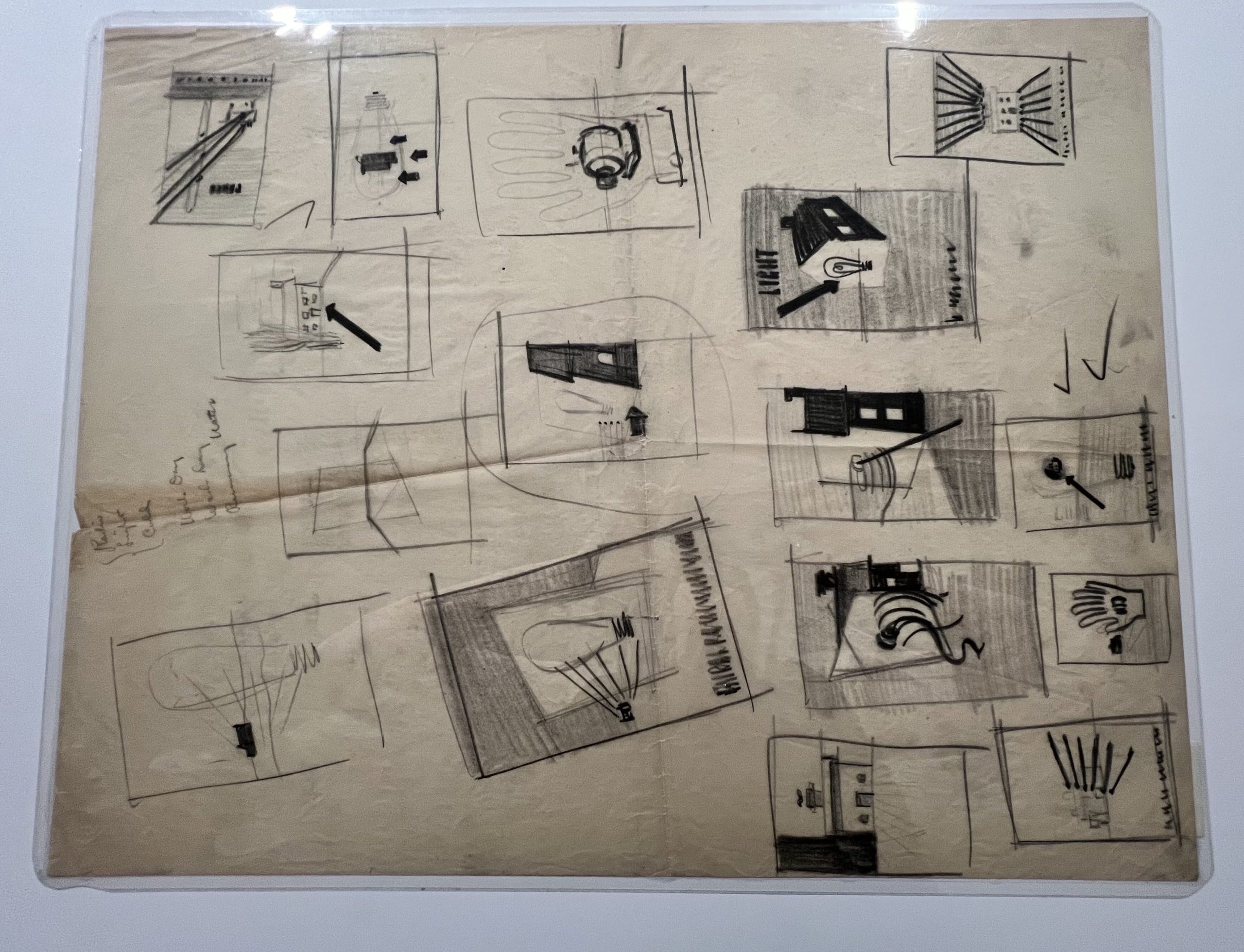

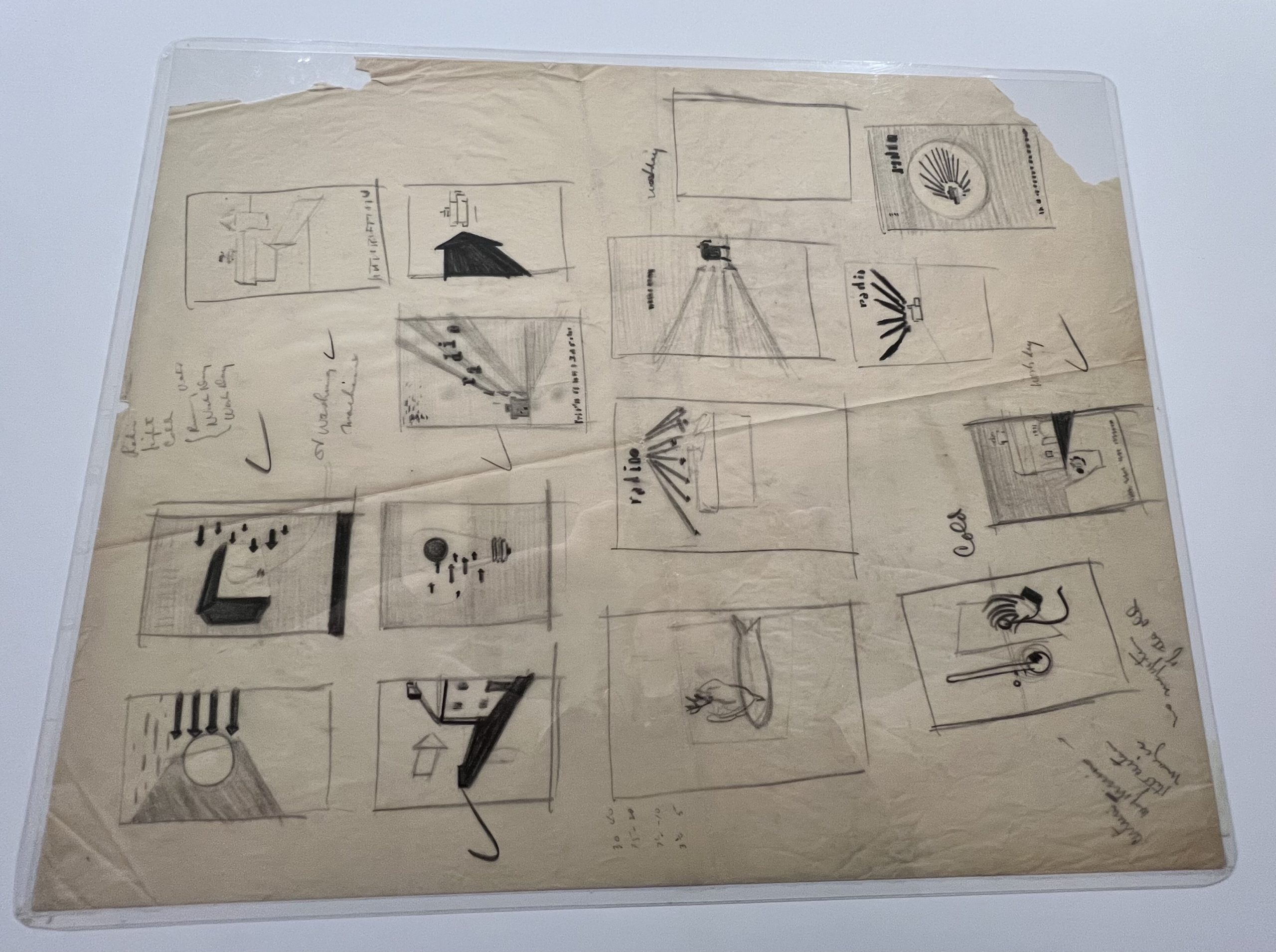

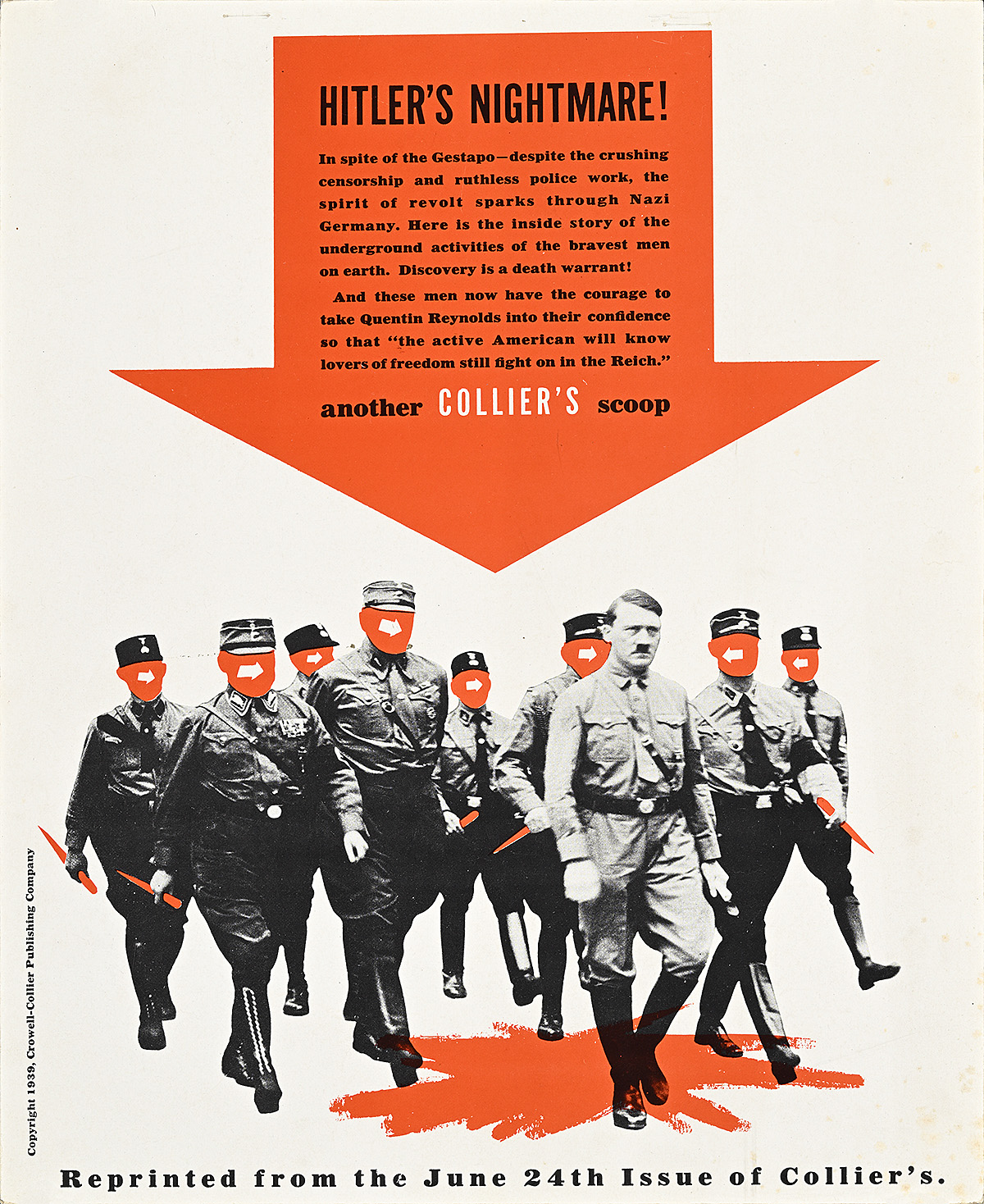

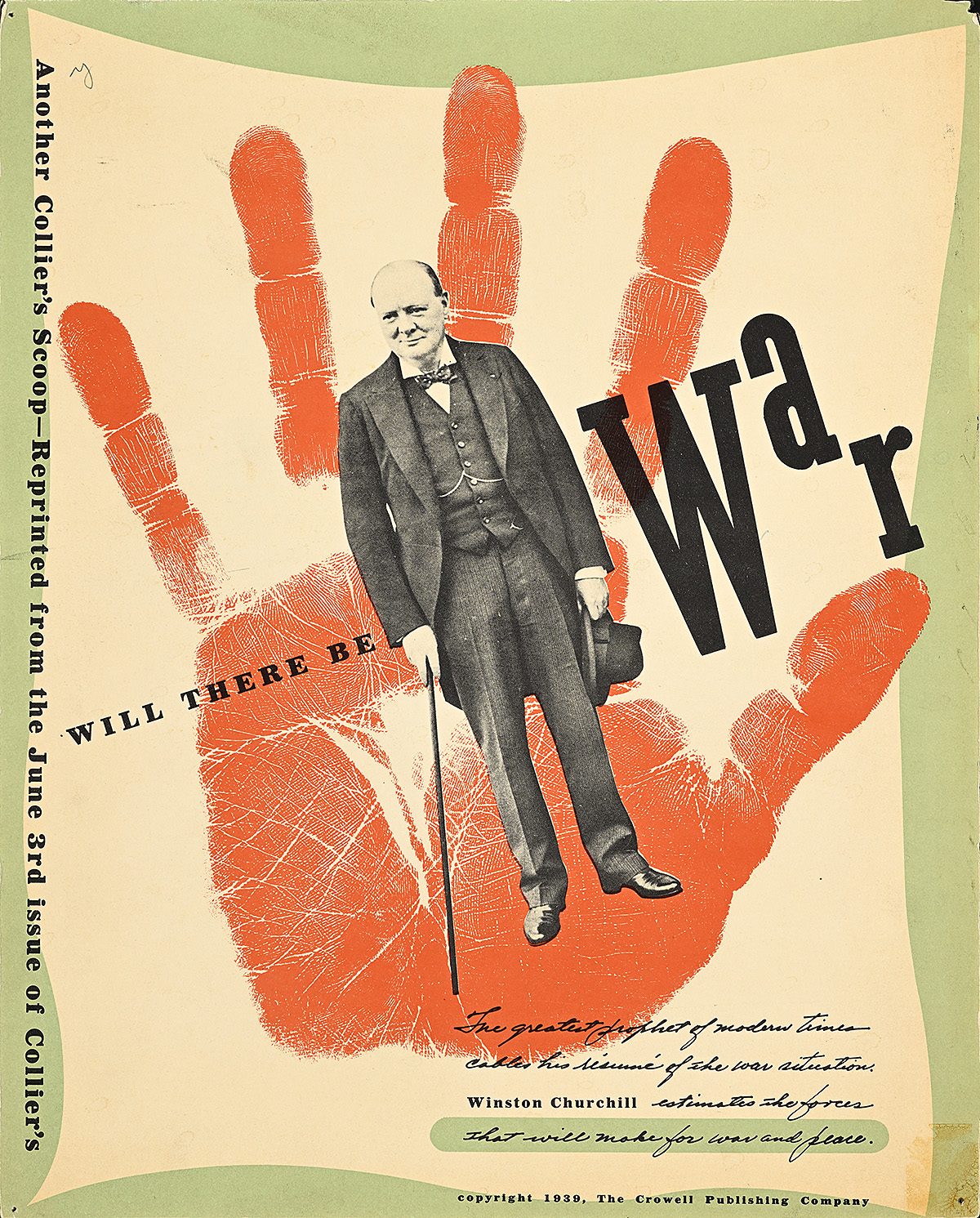

At school, Beall had been inspired by the new art coming out of Europe, often attempting to copy the work of Aubrey Beardsley and other popular illustrators. These styles, however, did not suit his talent. He began to order issues of the Art Directors Club of New York annual while also building his own library of secondhand art books and periodicals. Through these publications, he was exposed to a new world of design possibilities, including Soviet photomontage, Swiss grid systems, and German layouts.

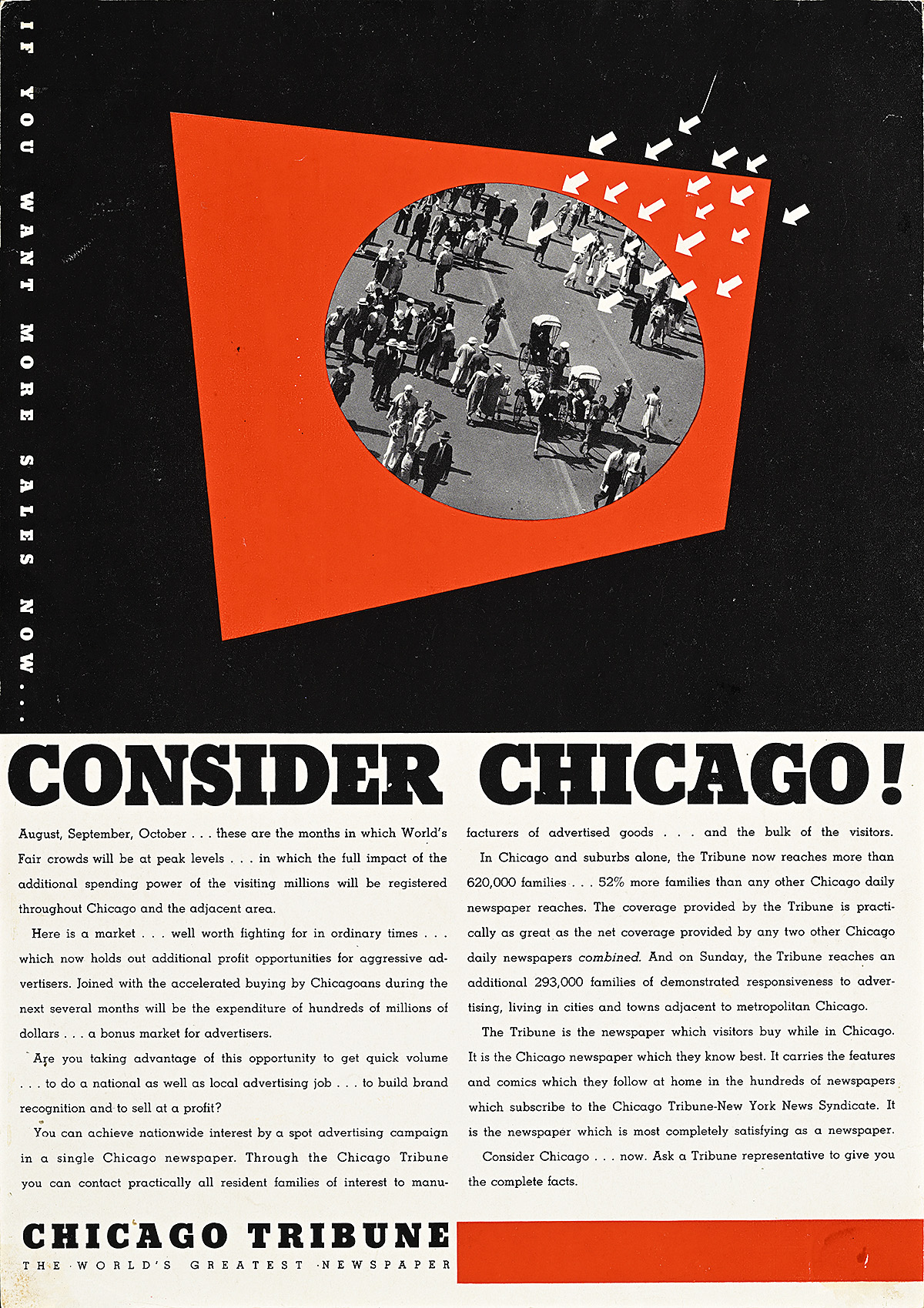

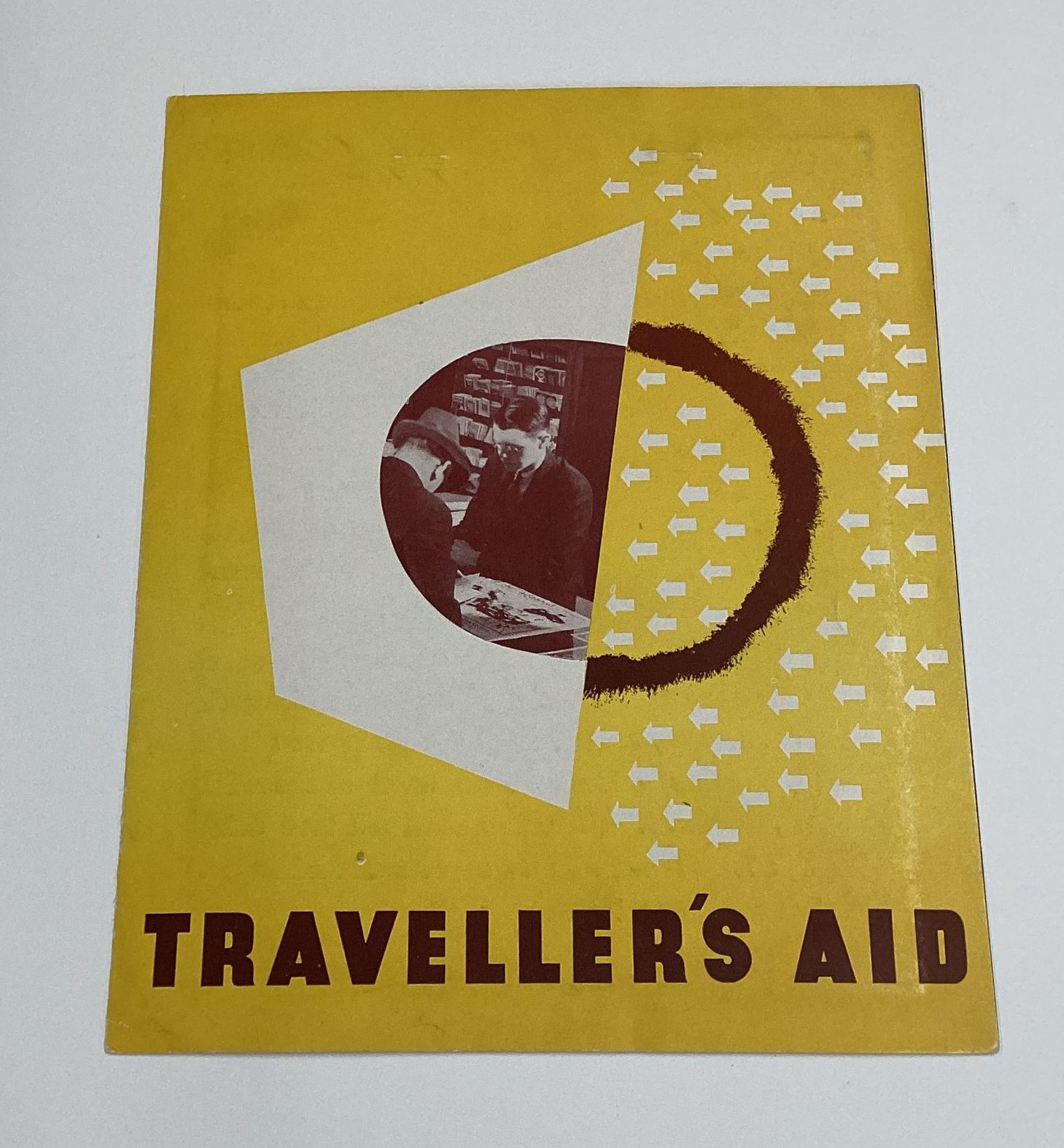

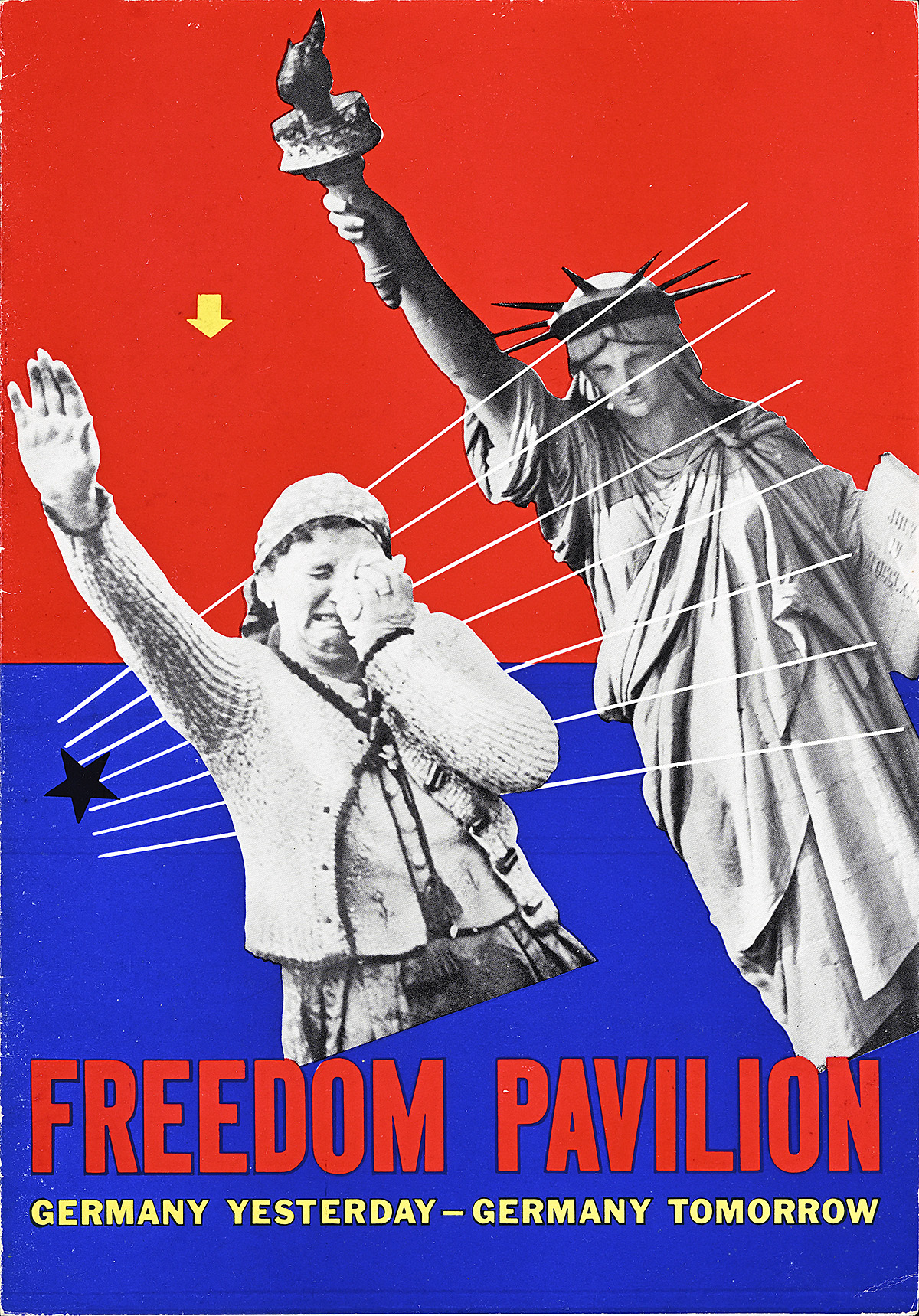

Aware that Americans were generally distrustful of overly intellectual and visually obtuse European modernism, Beall deftly translated and advanced these artistic concepts to create a new kind of American art, one that distilled the essence of various avant-garde movements and combined it with clear communication and a commercial sensibility.

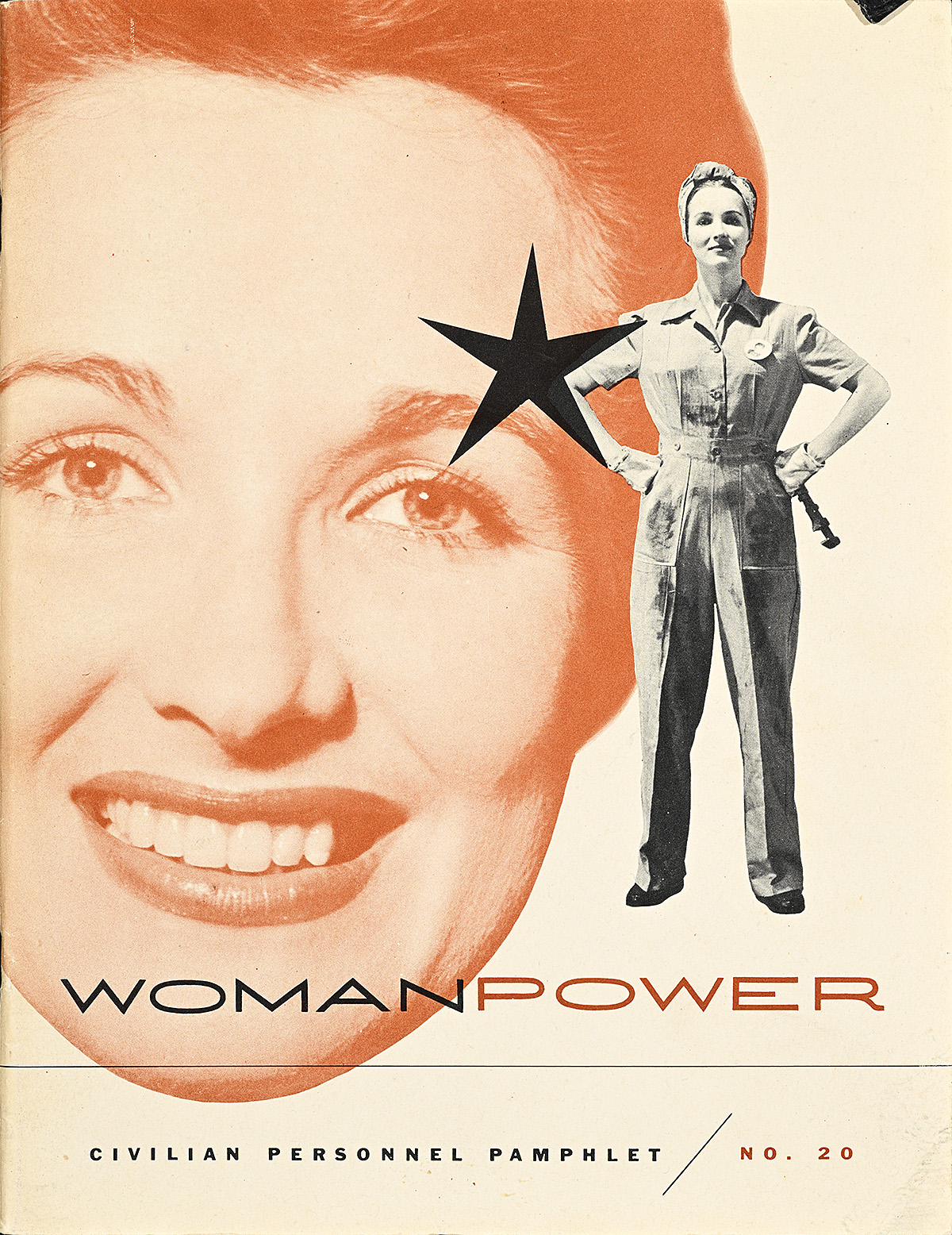

After graduating with a degree in art history from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1926, Beall opened his own studio in the city’s South Side, noting that the only way for an artist to make a living in the United States was as a commercial illustrator. Not wanting to work for a larger agency, he created hundreds of illustrations on spec, hoping that a company would purchase one of his designs. By the end of the 1930s, his unique brand of American modernism would change how the U.S. government communicated with its diverse population, anticipating the juggernaut of American mid-century corporate design and branding.

This exhibition would not be possible without the support of Mark and Maura Resnick and Michael Kleeman.

This exhibition is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.