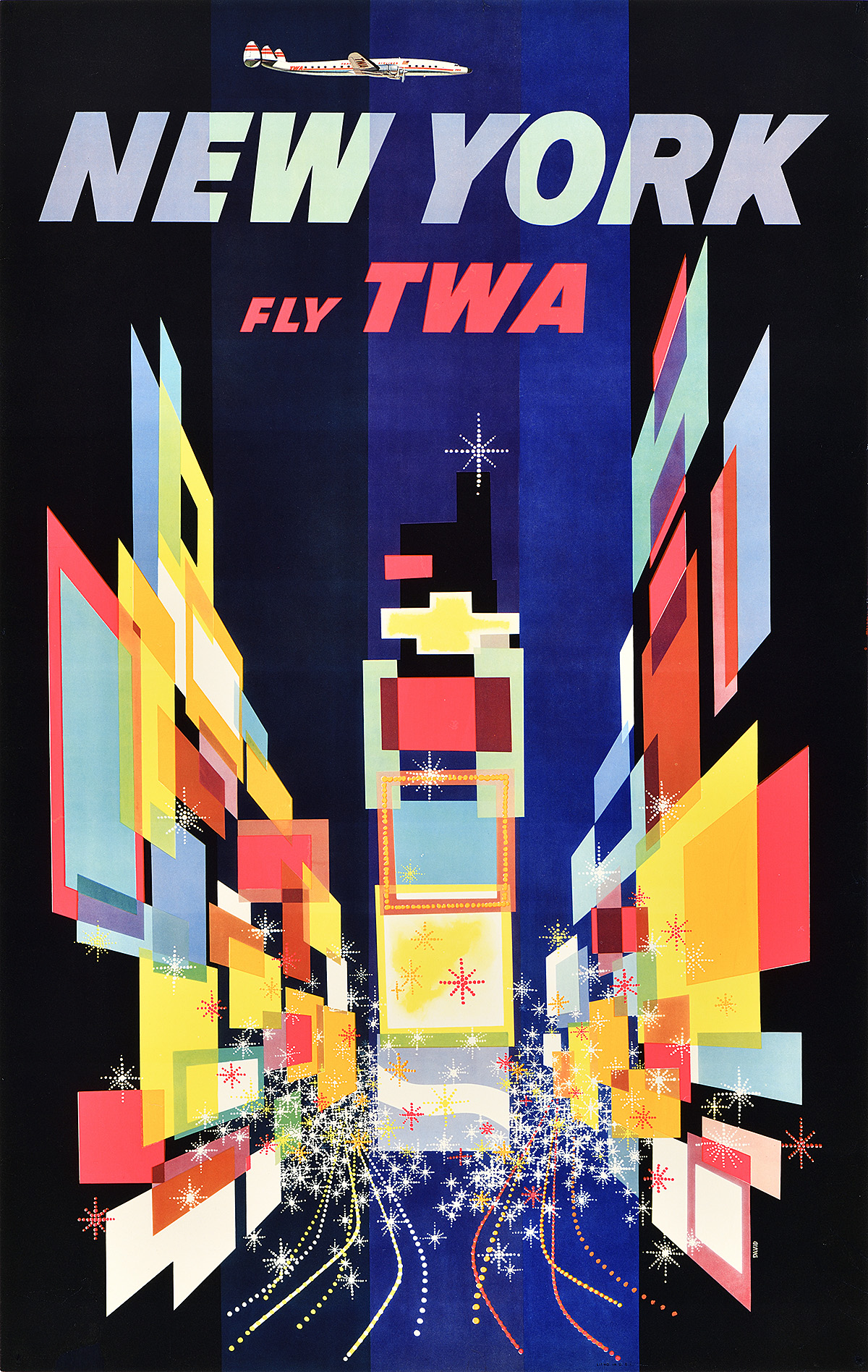

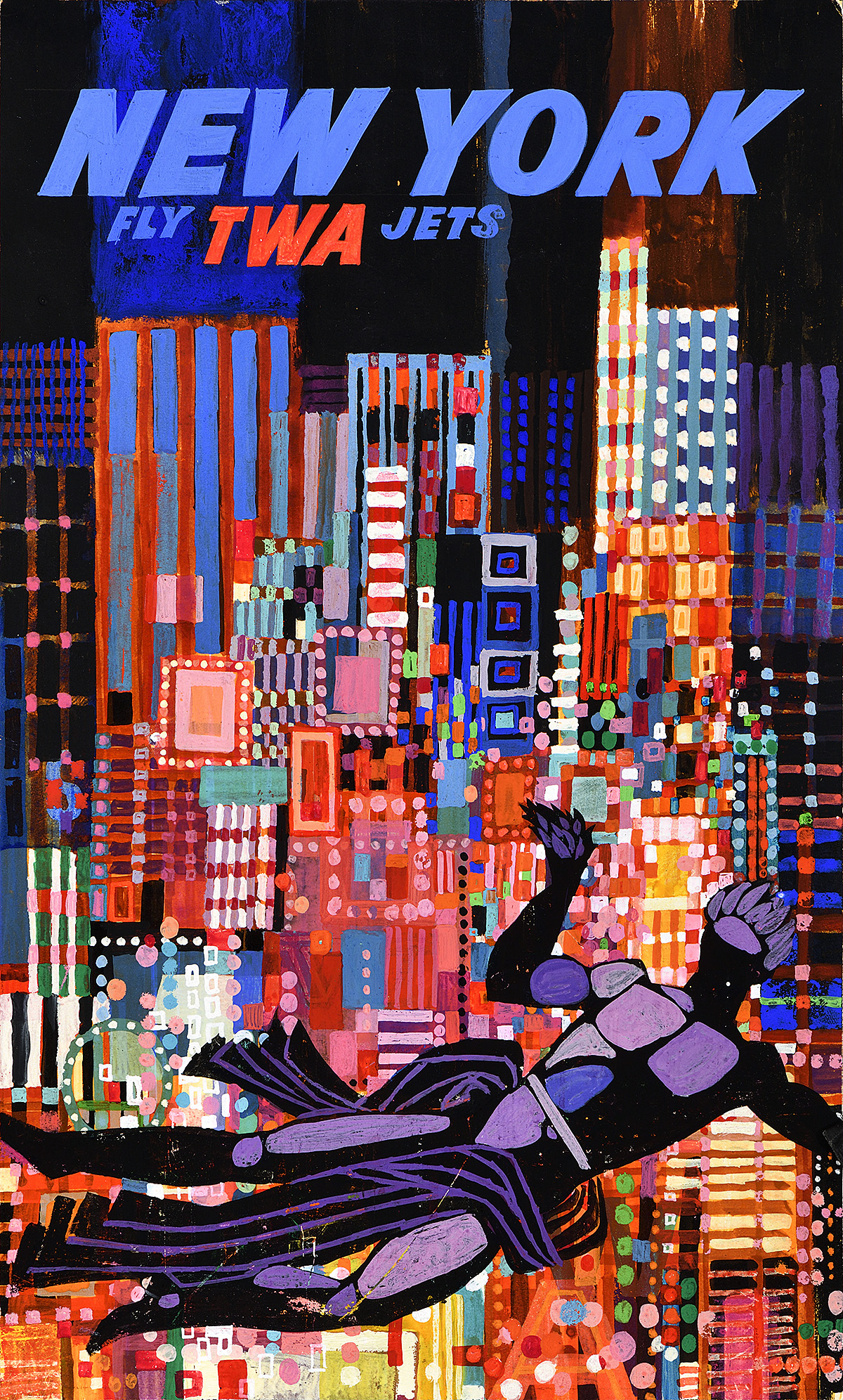

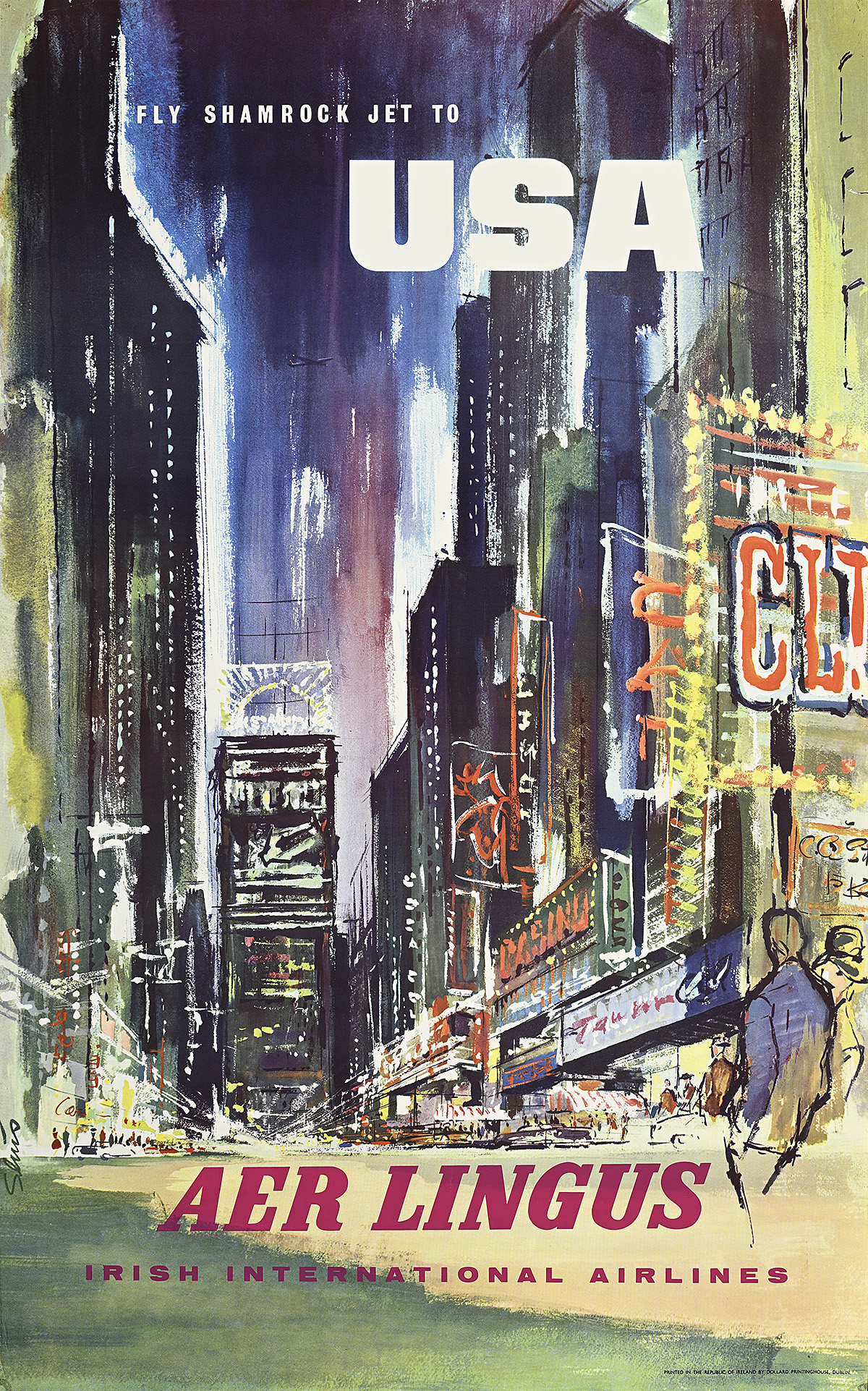

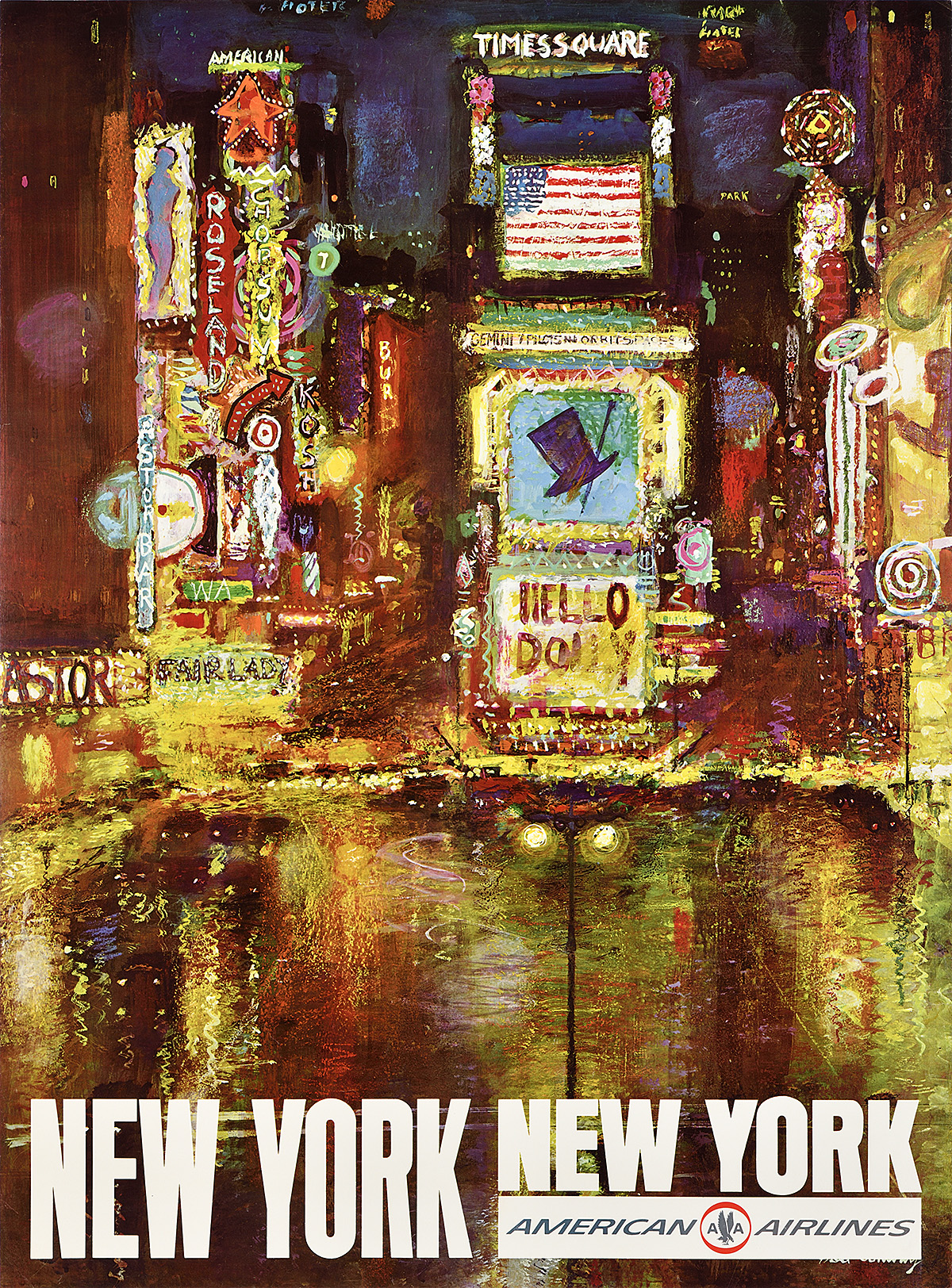

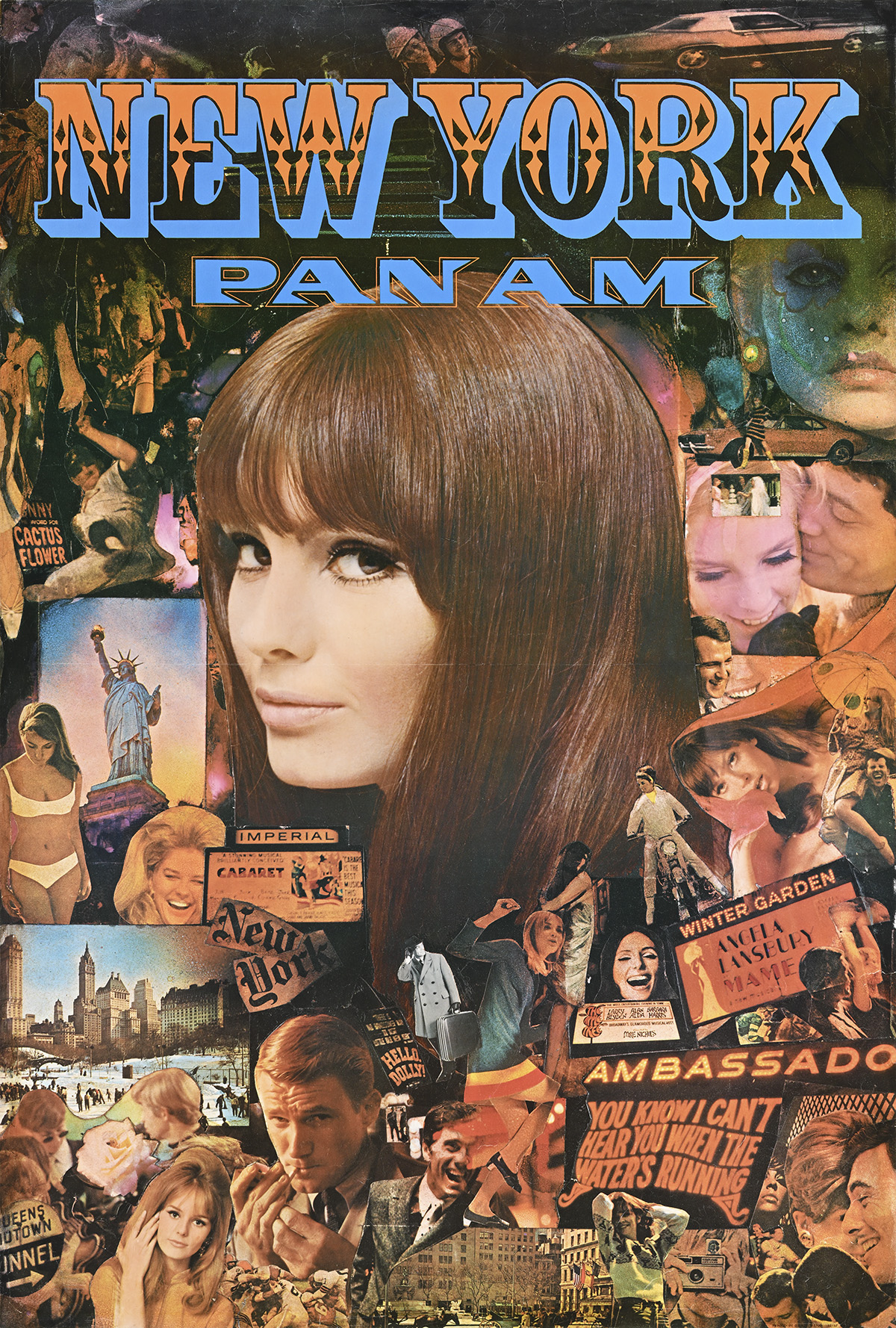

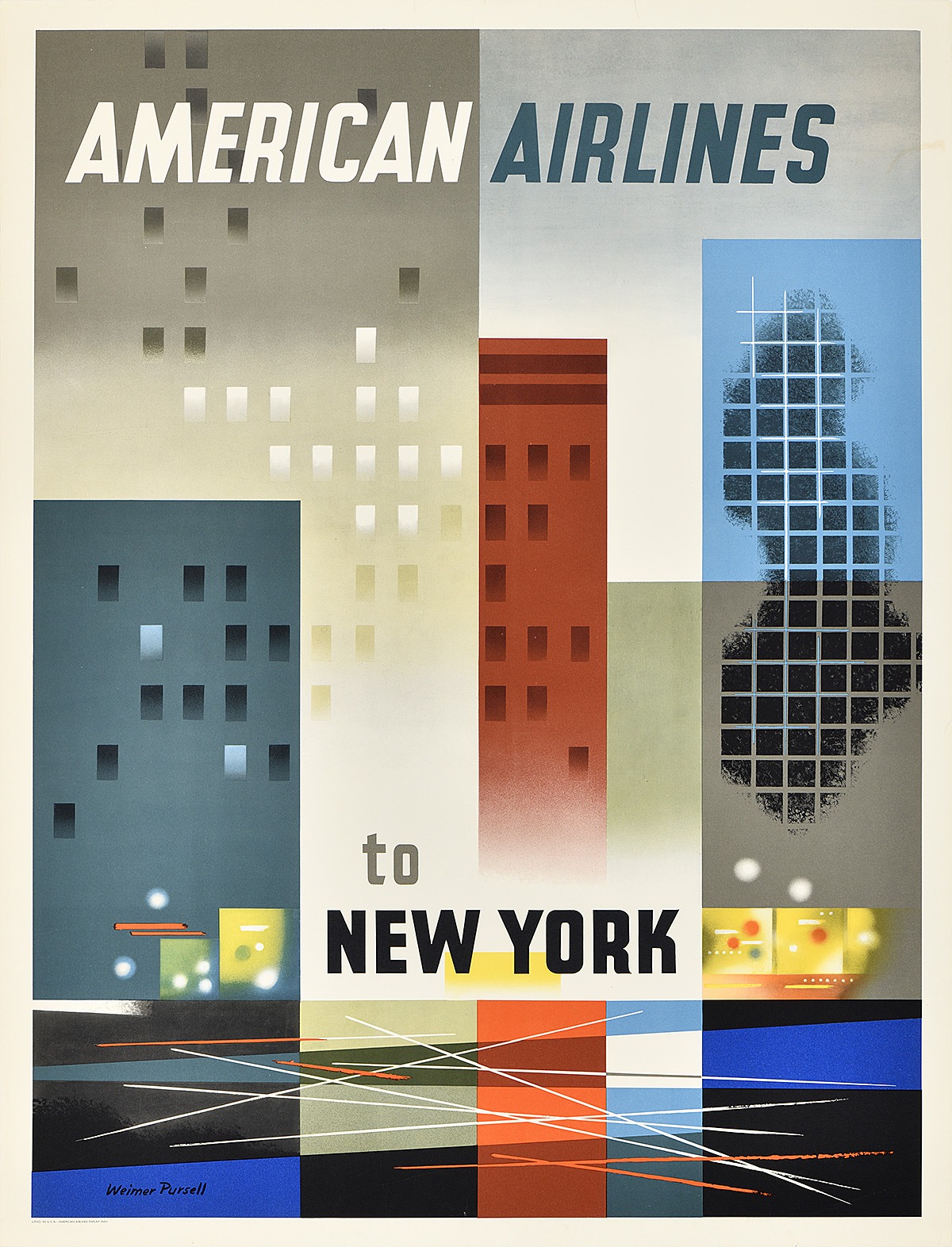

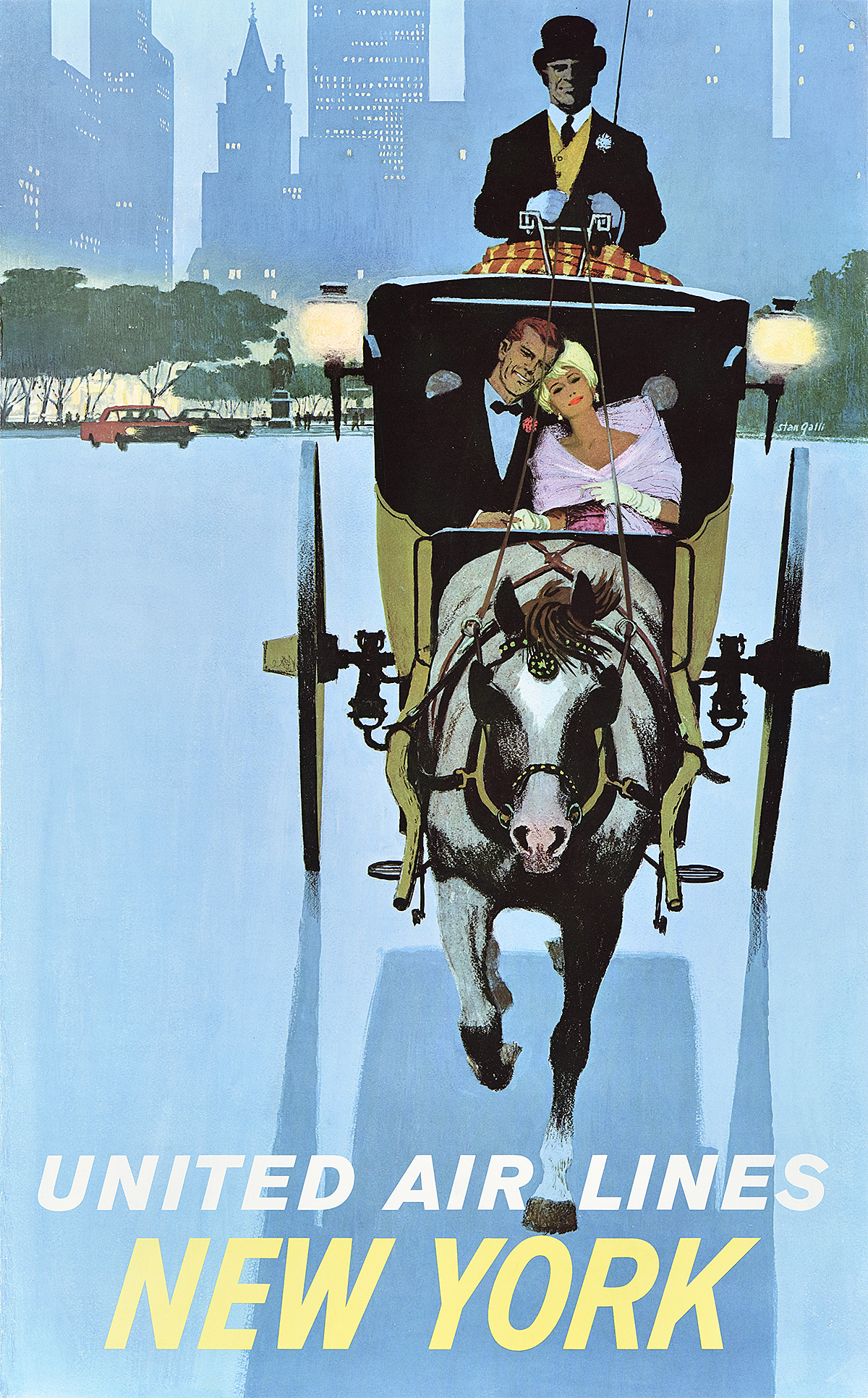

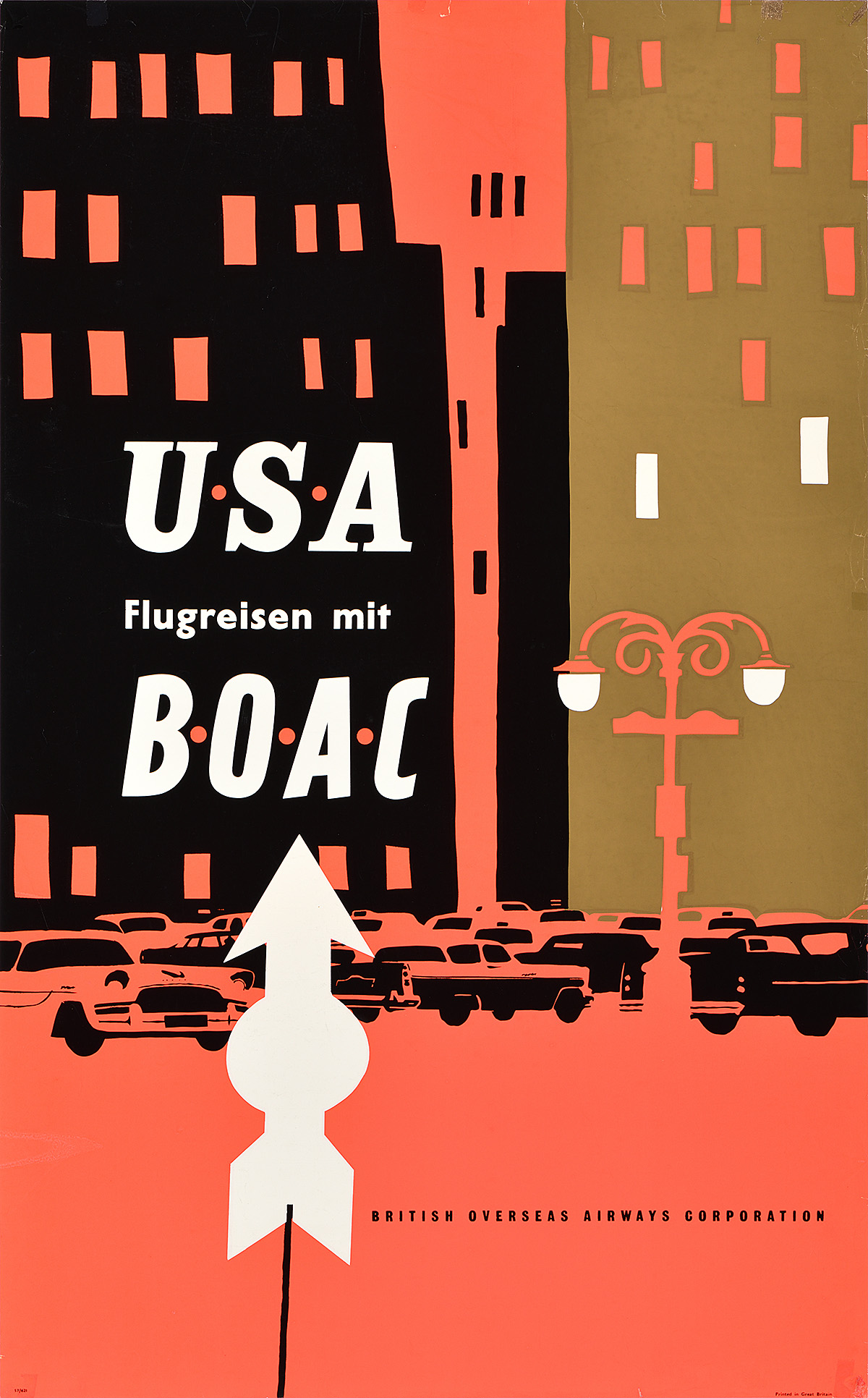

Wonder City of the World: New York City Travel Posters

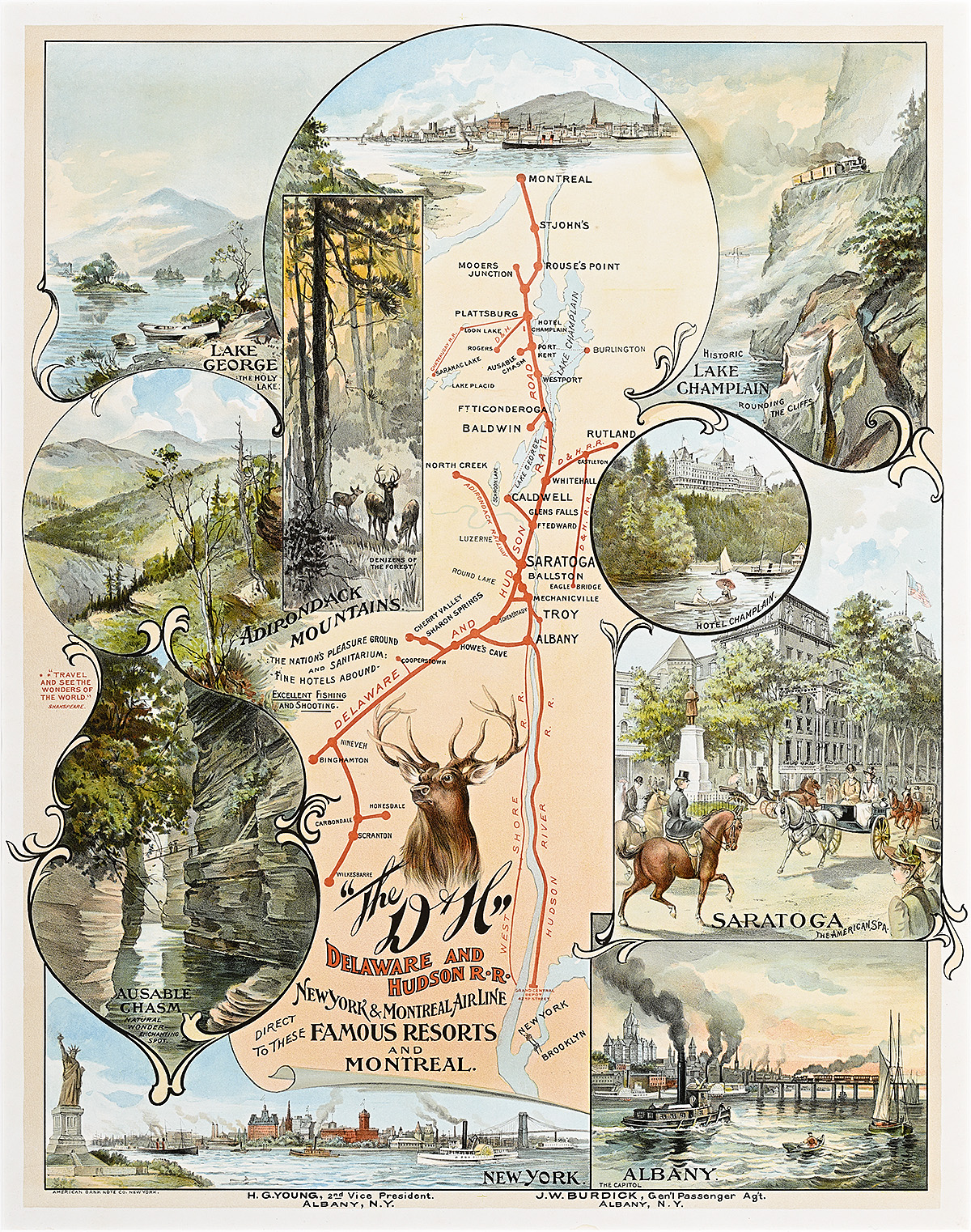

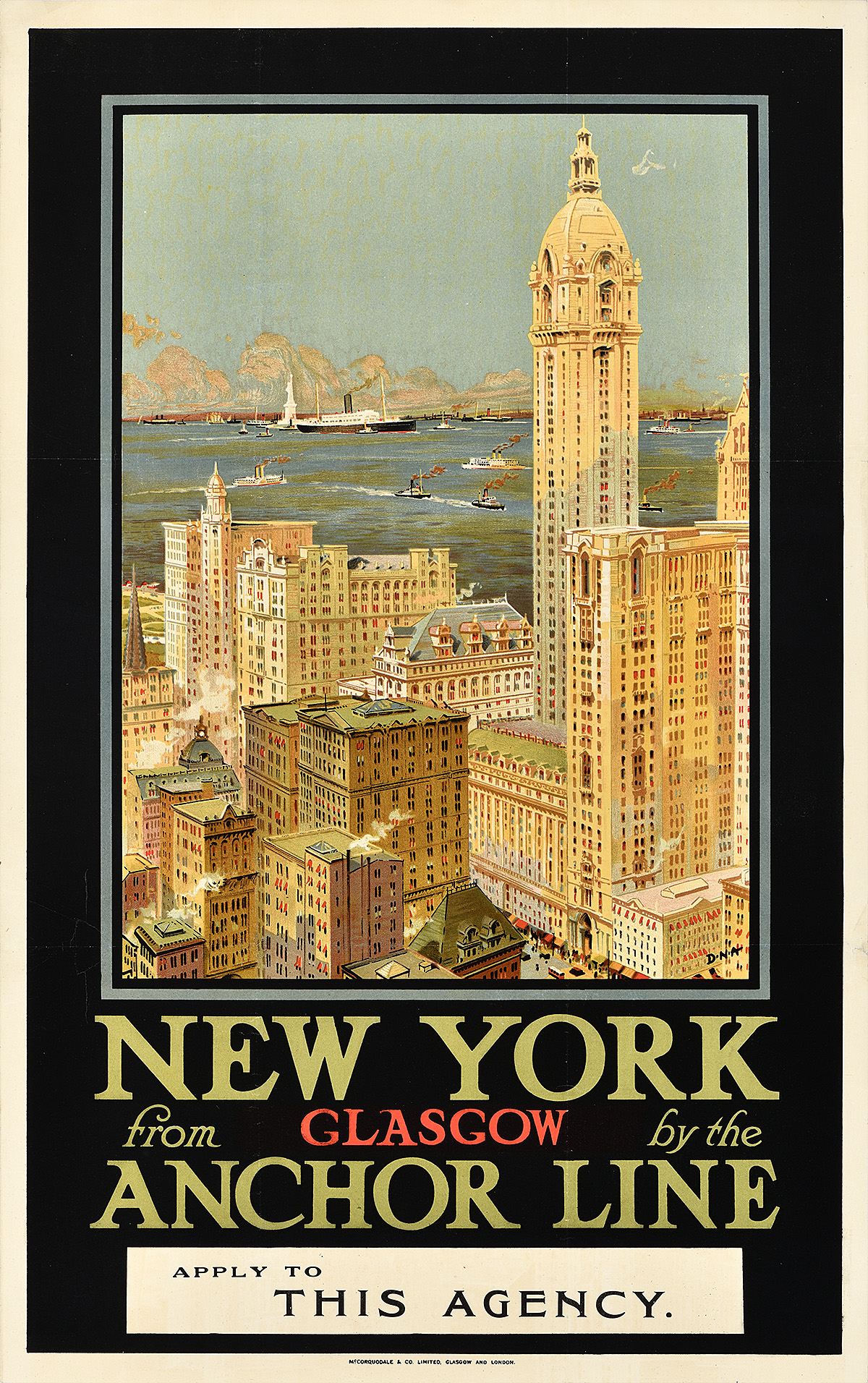

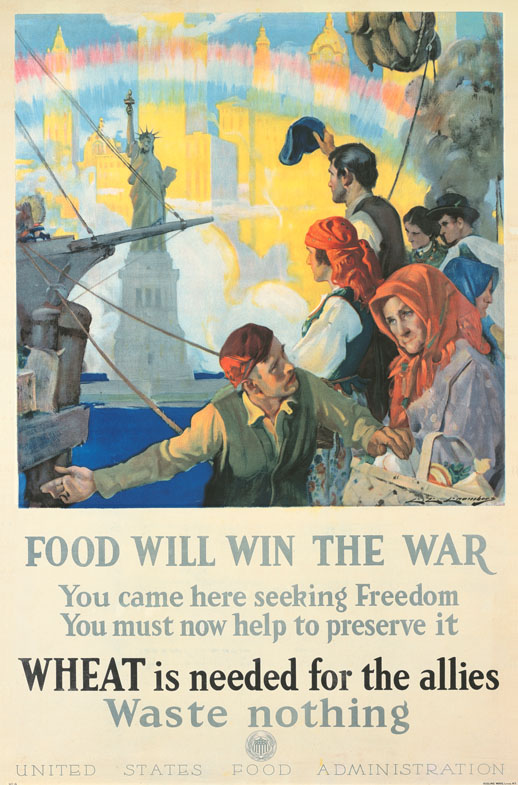

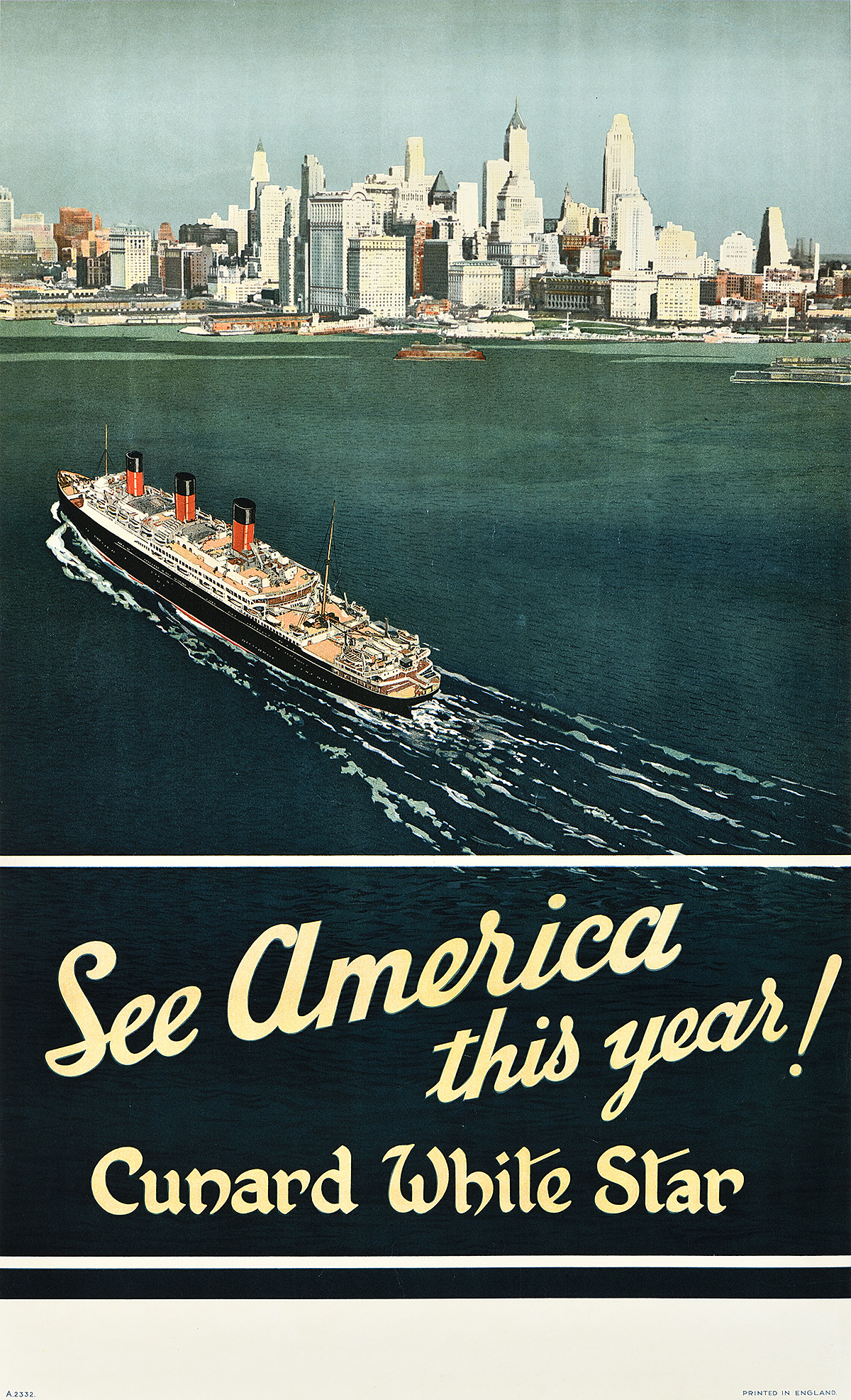

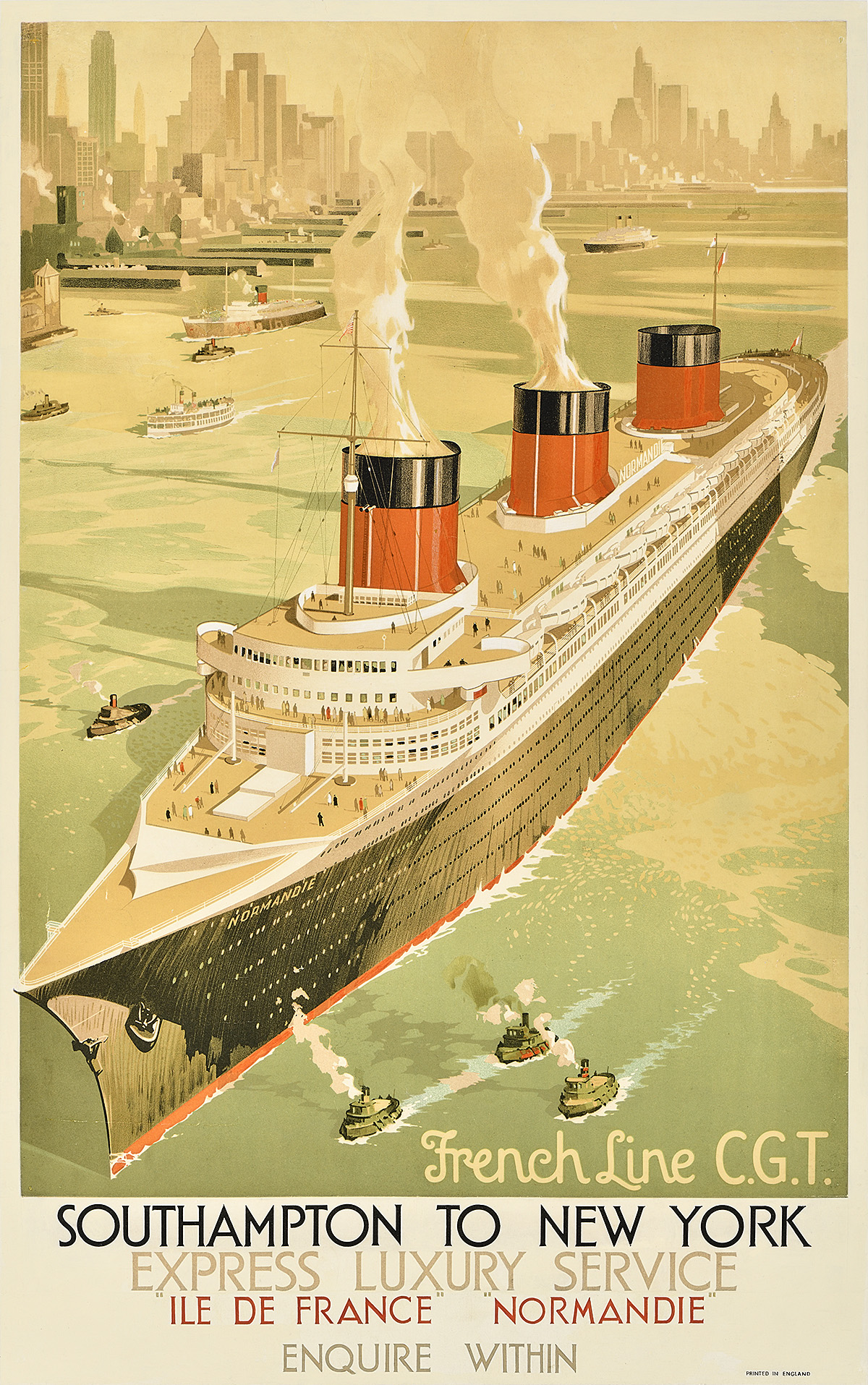

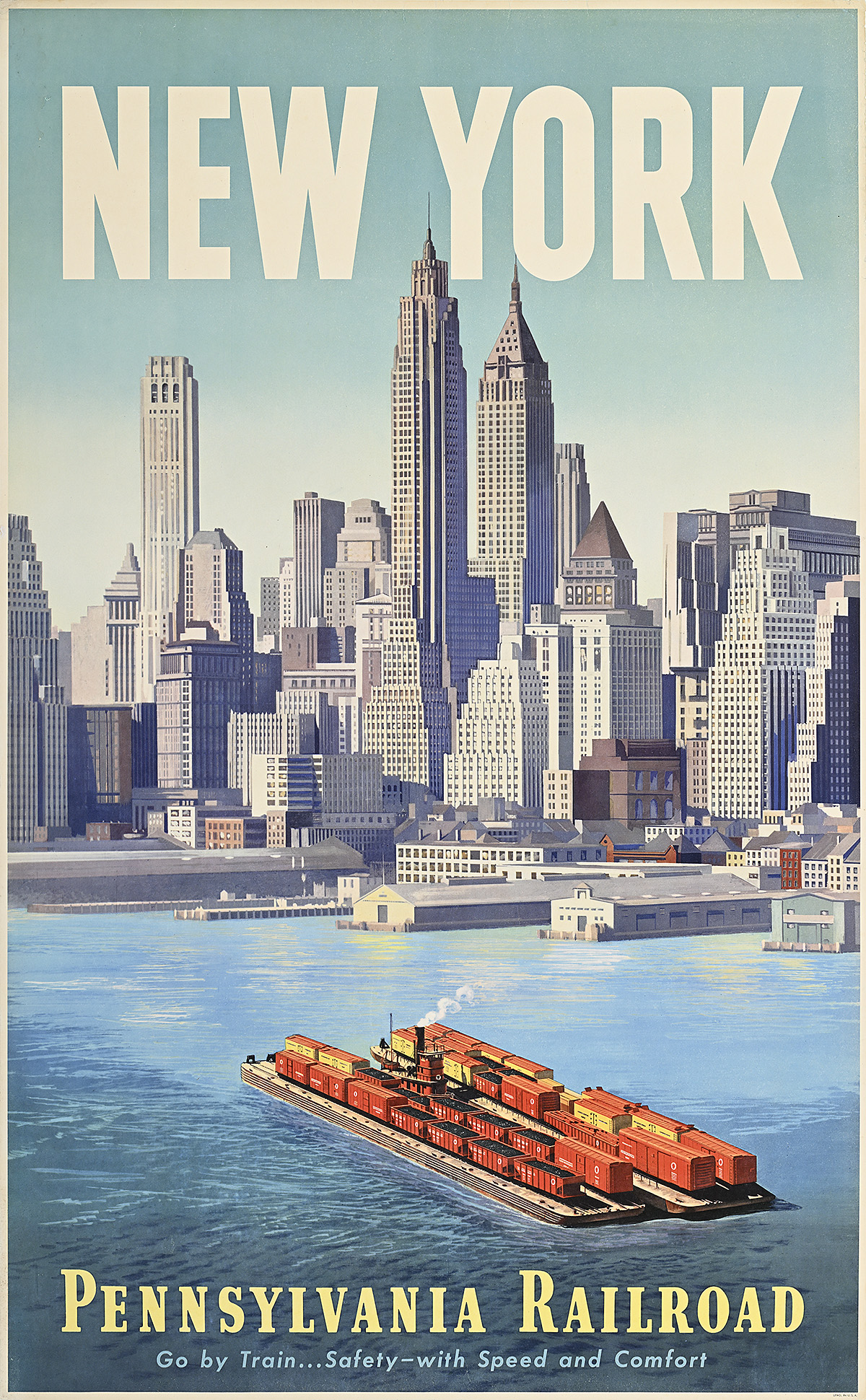

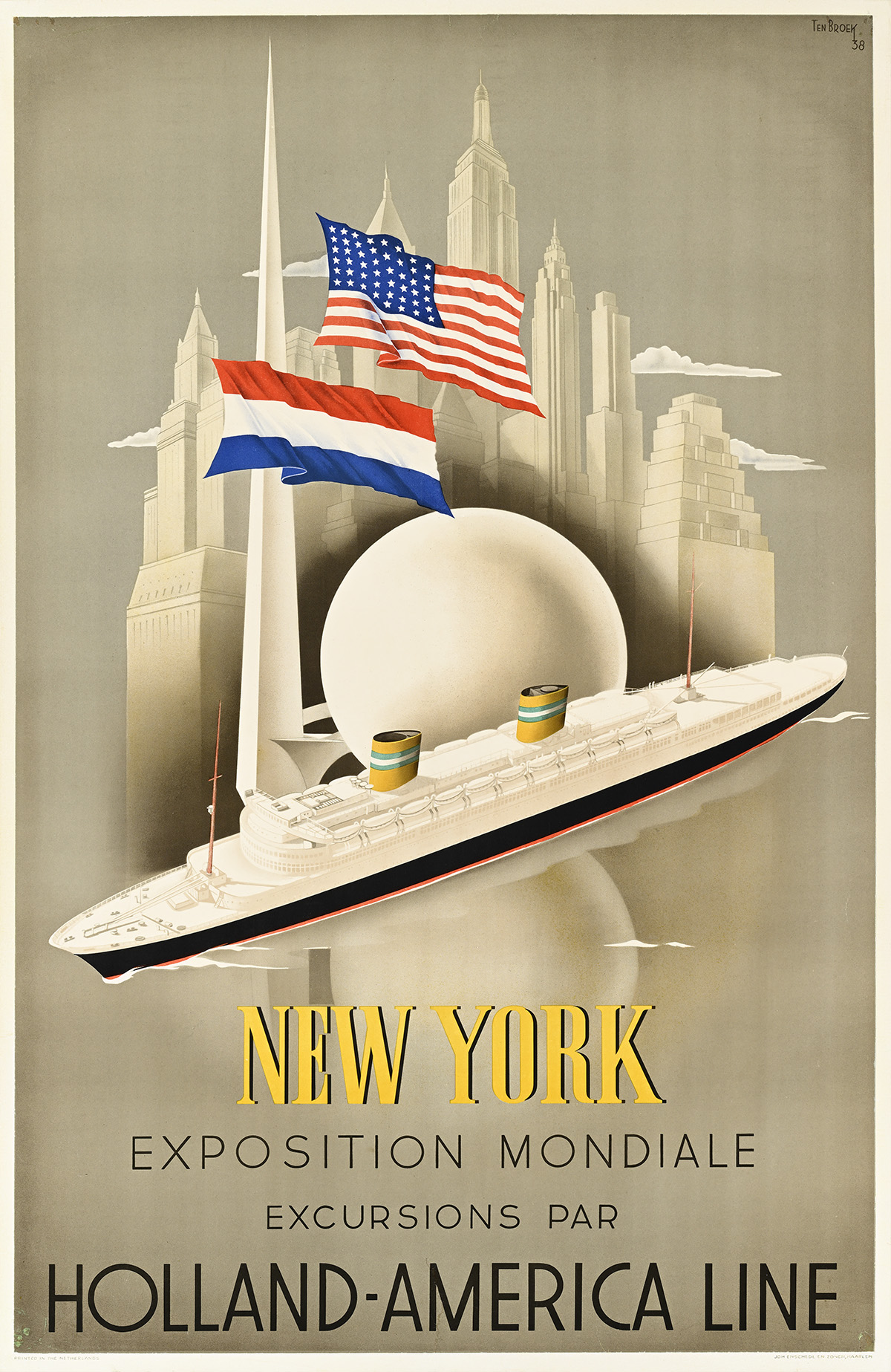

New York wasn’t always a “Wonder City.” For centuries, the area at the mouth of what is now New York Harbor was home to the Lenape people. In 1524, the first European explorer, Giovanni da Verrazzano, sailed into what is now New York Bay, and in 1609, almost a century later, Henry Hudson’s exploration on behalf of the Dutch East India Company helped establish New Amsterdam, a Dutch-controlled settlement. With approximately 520 miles of coastline—more than Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami, and Boston combined—New York was an important port long before it was a prominent tourist destination. Its natural, deep-water harbor and protected landings made it a desirable, accessible, and safe haven for ships. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 connected the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, giving merchants access to the interior of the country and making New York Harbor even more commercially attractive. By the time the Civil War began in 1861, New York was one of the three biggest ports in the world.

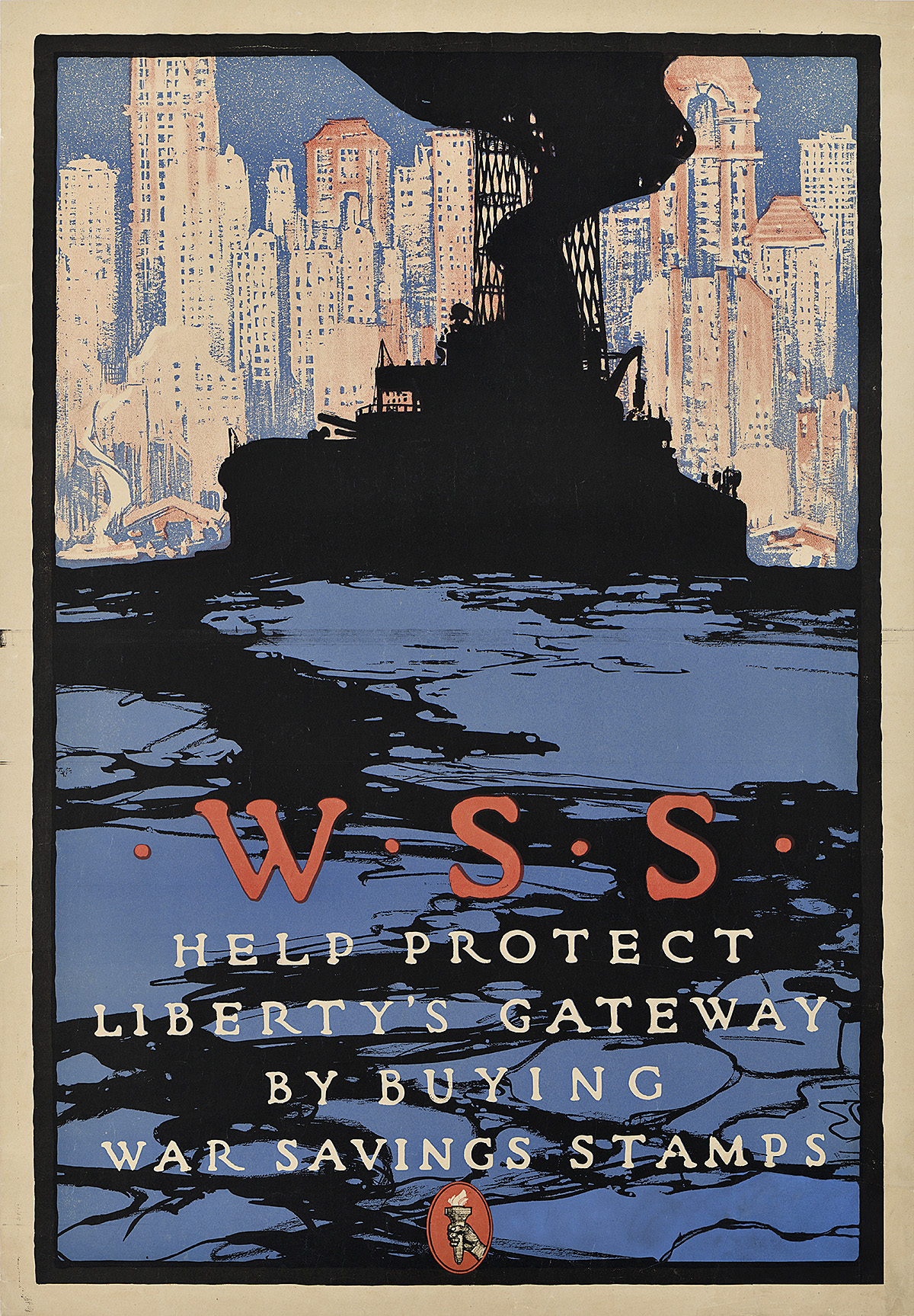

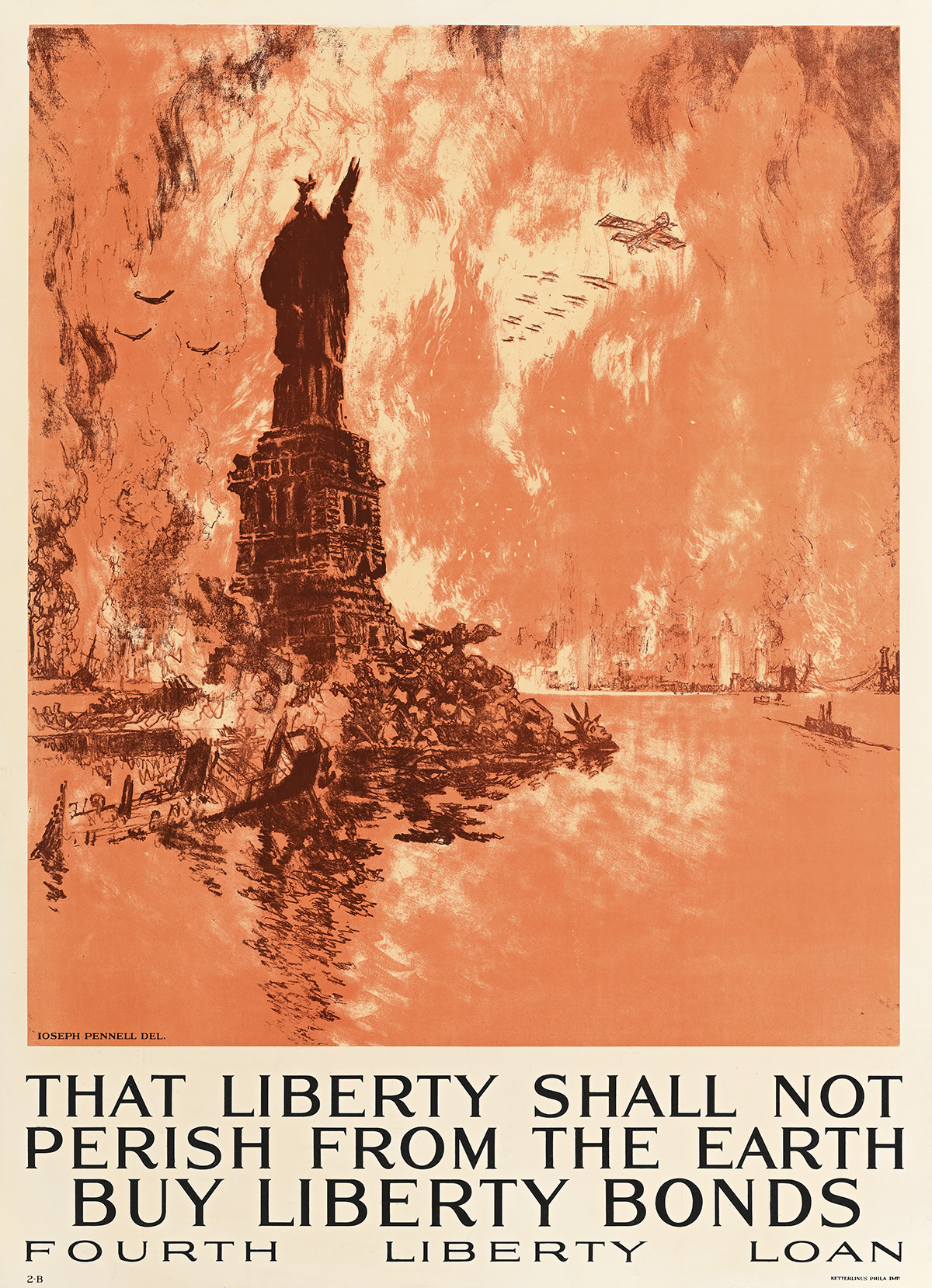

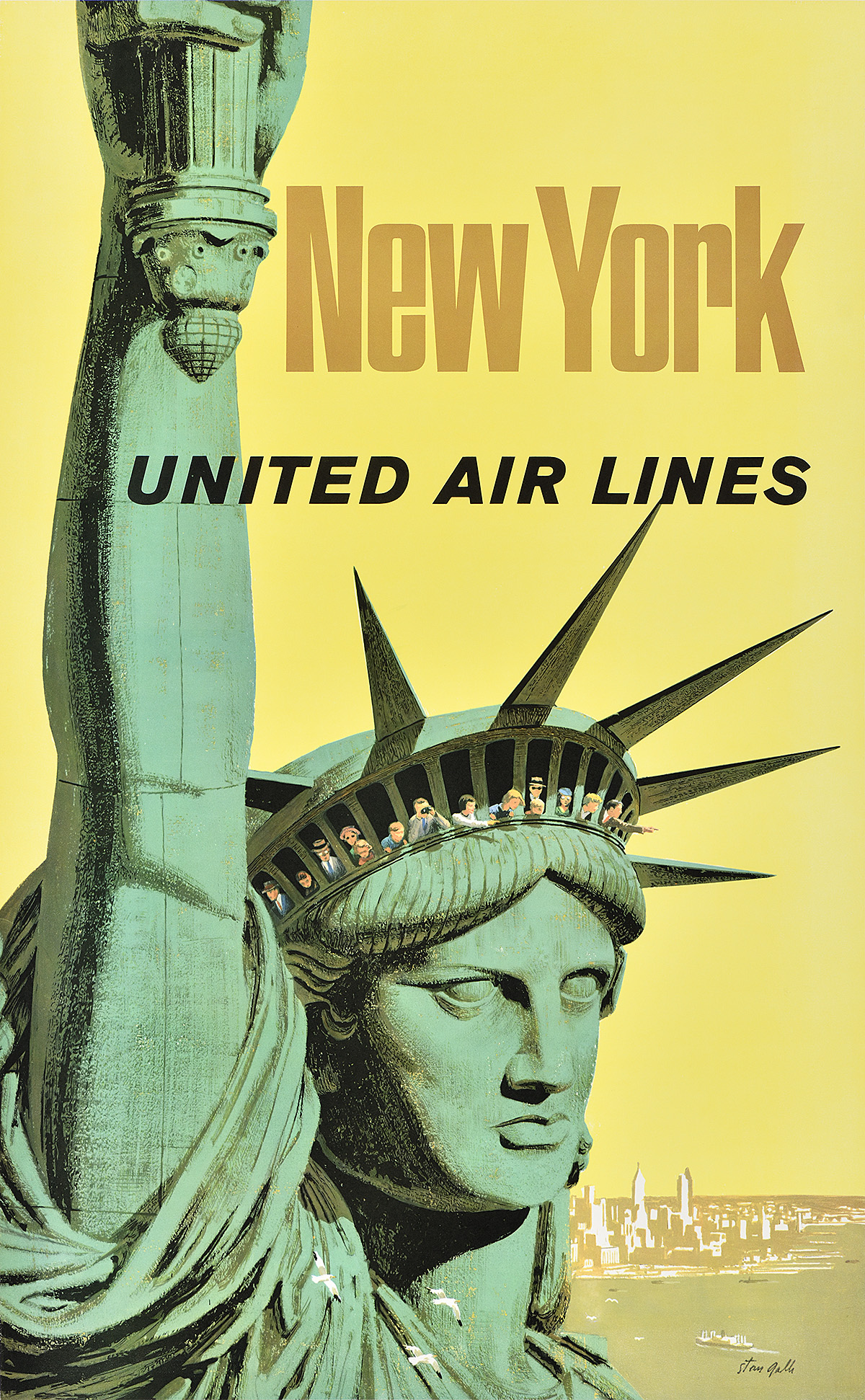

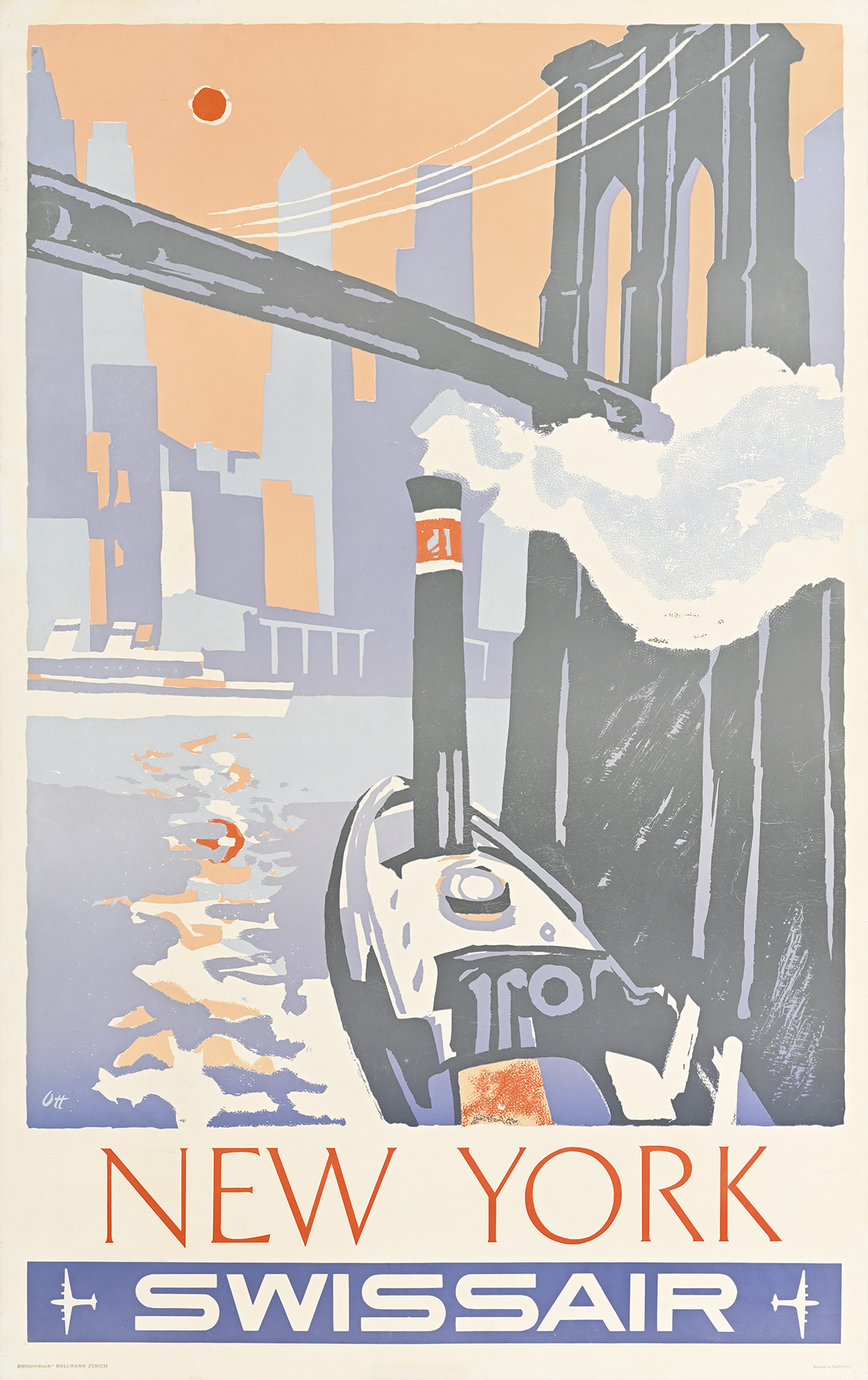

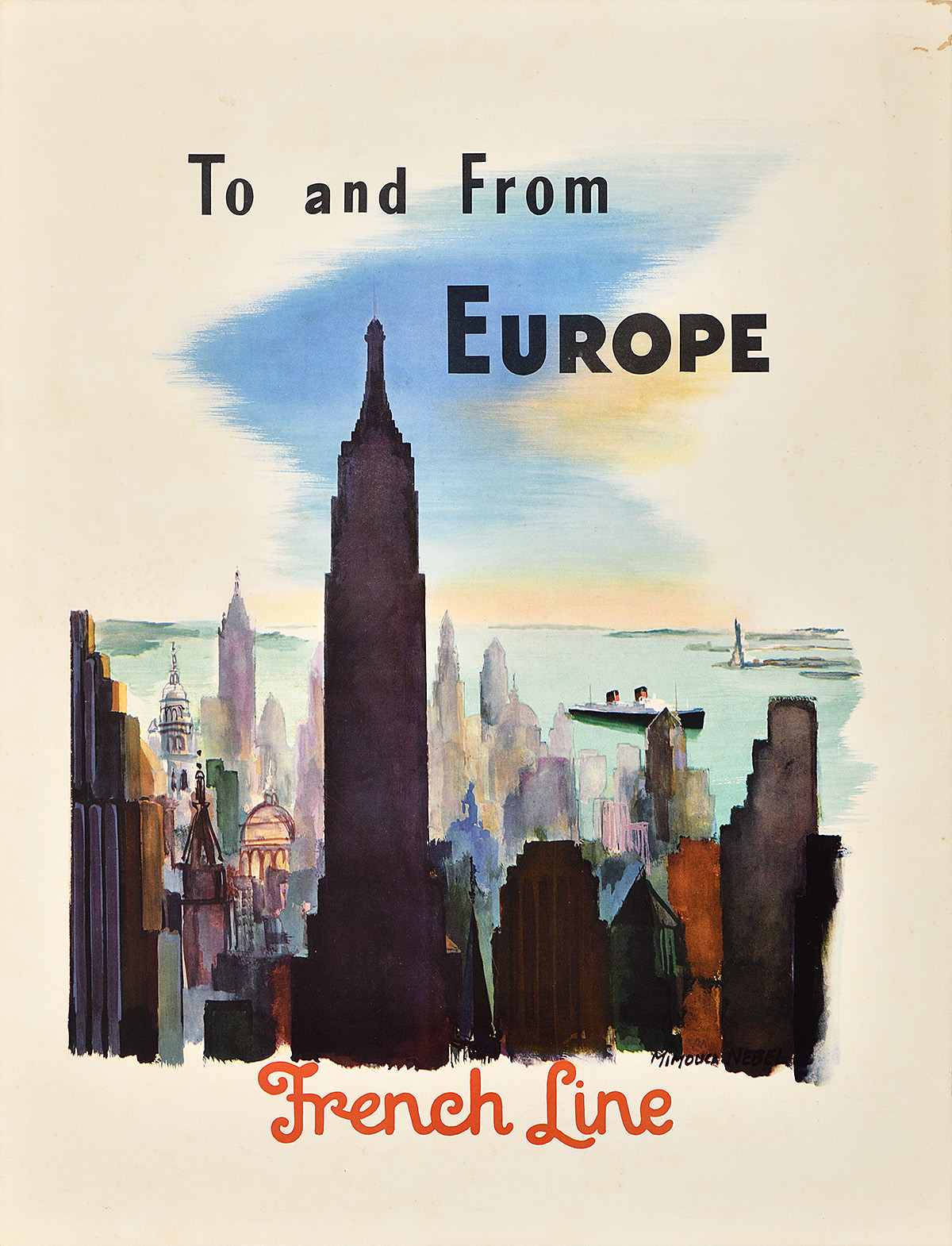

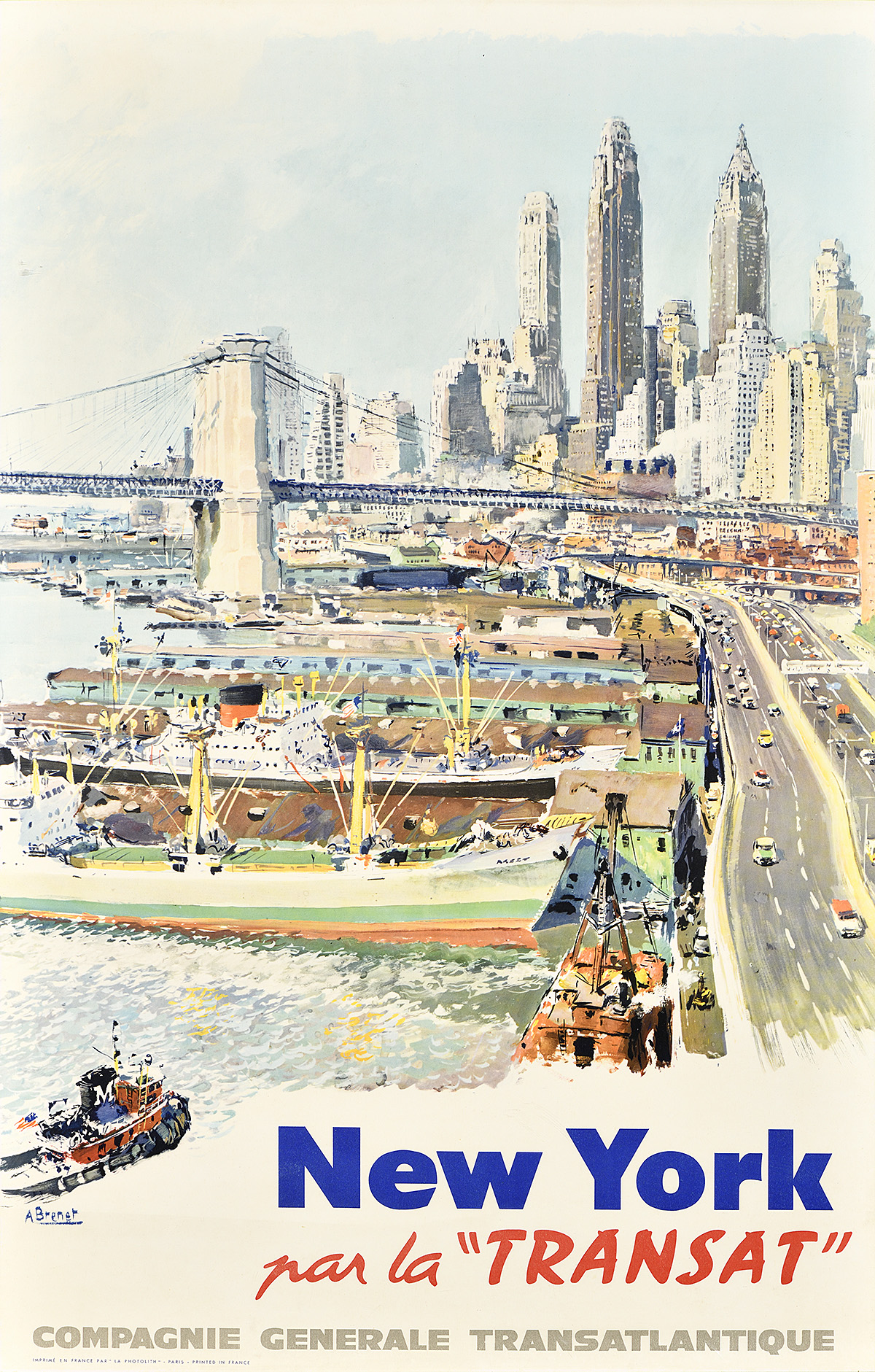

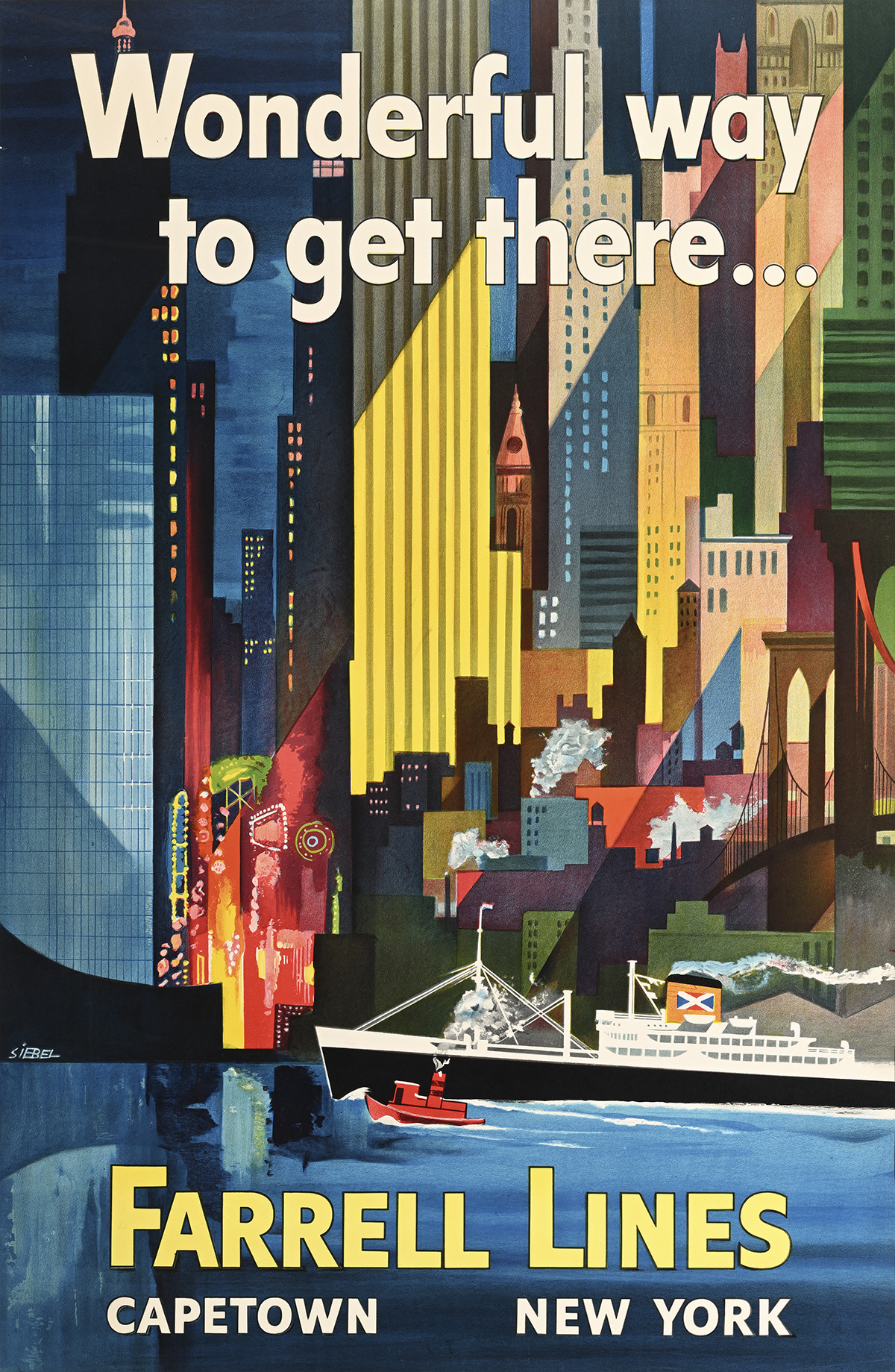

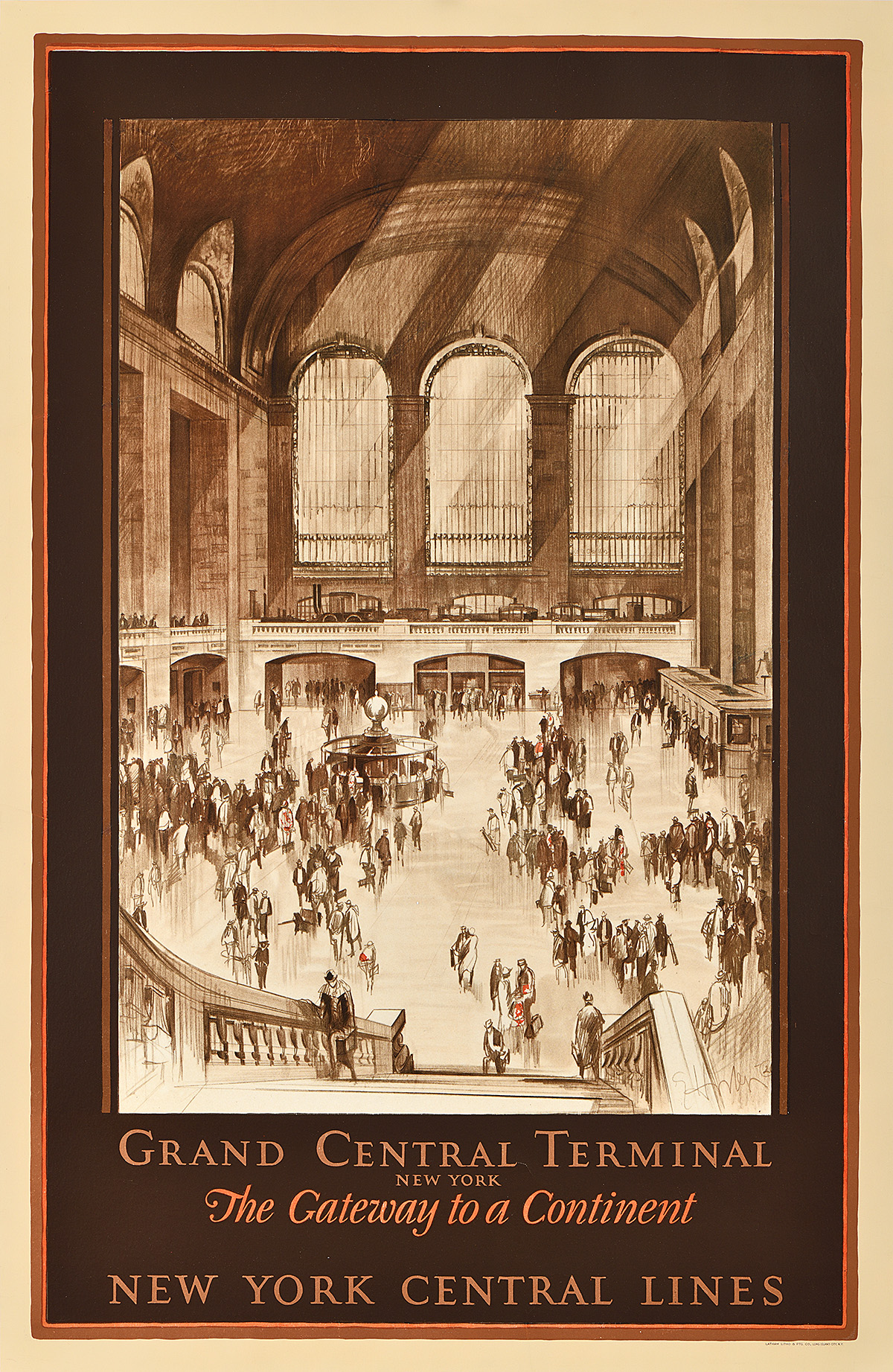

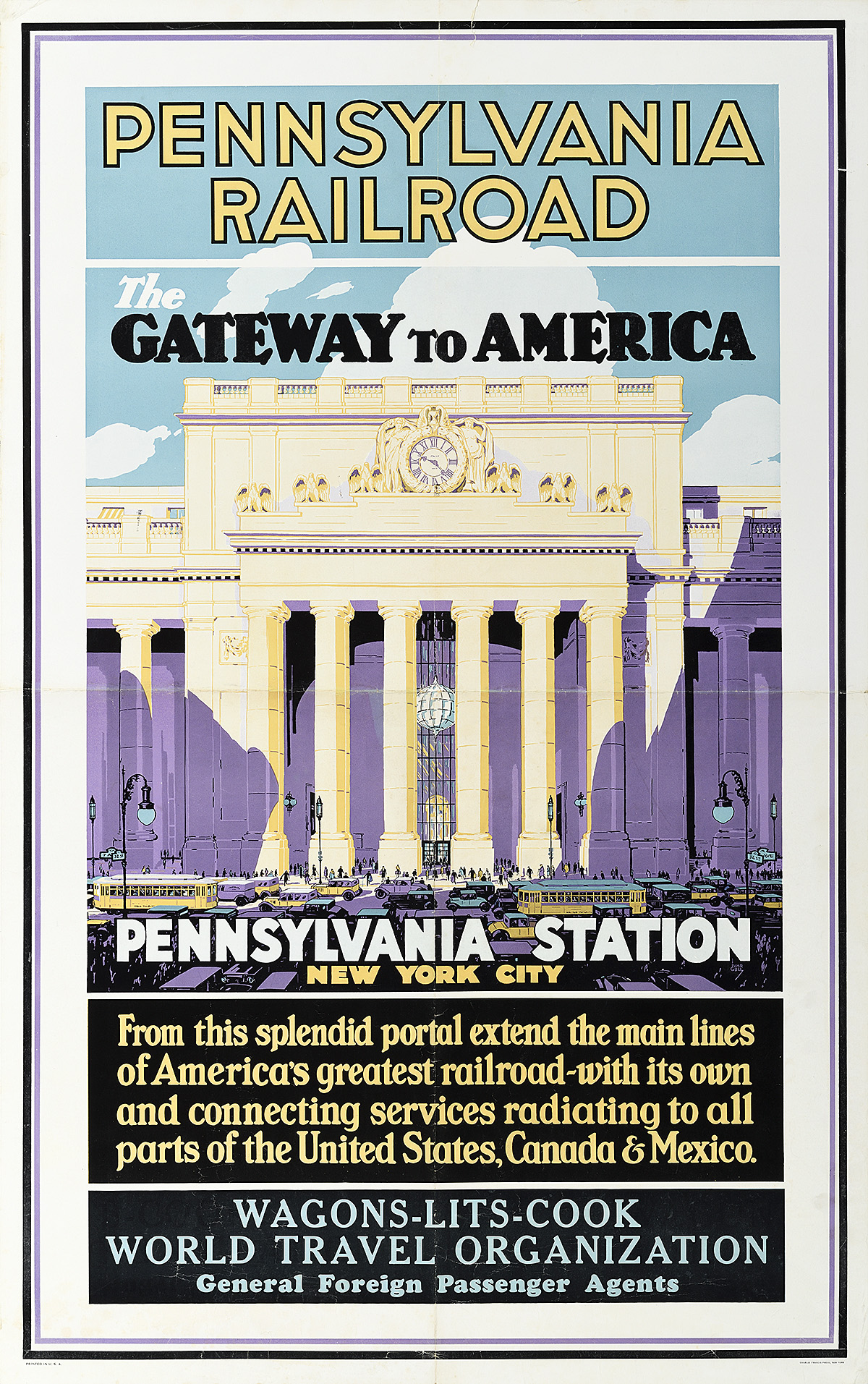

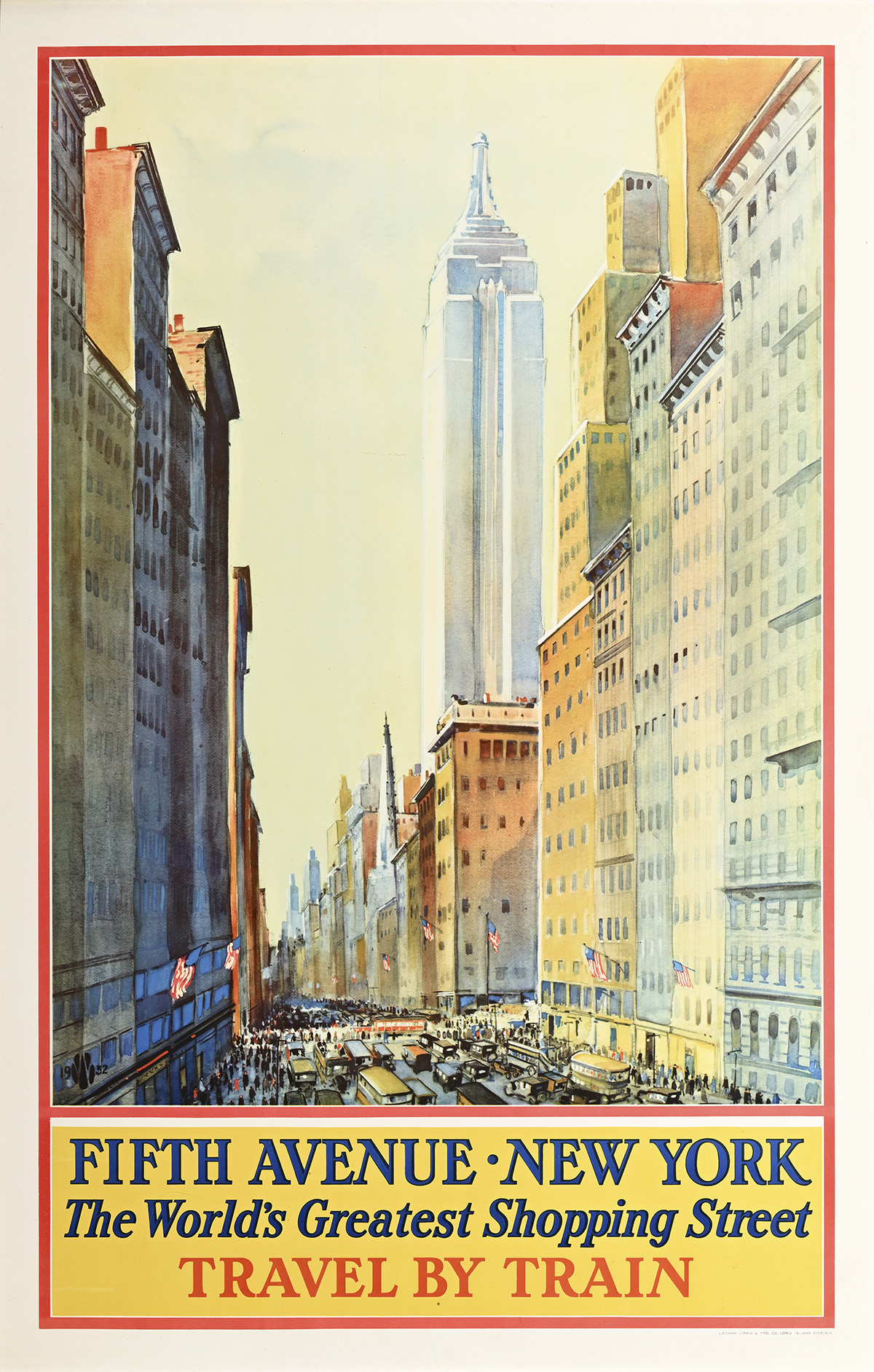

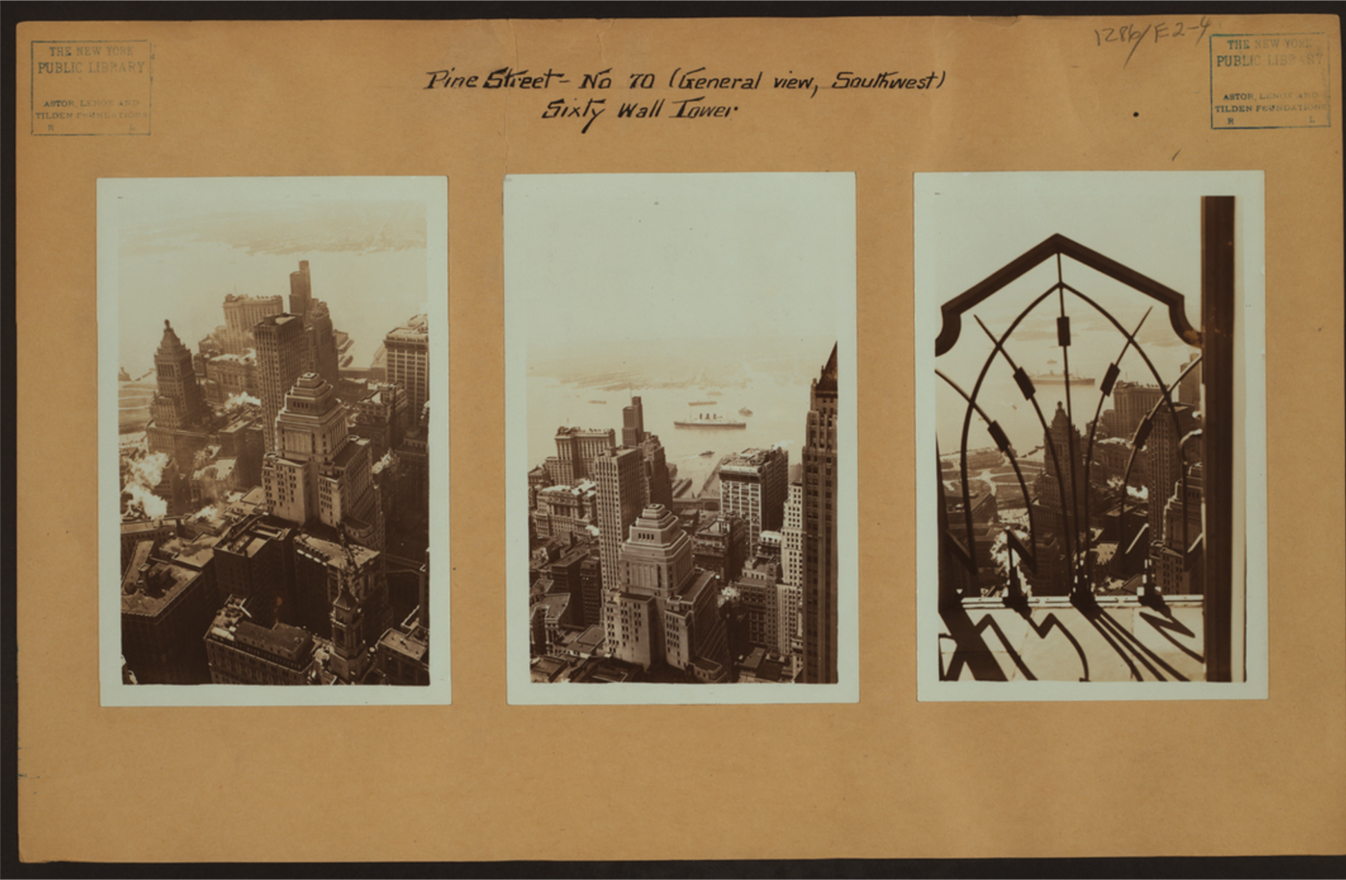

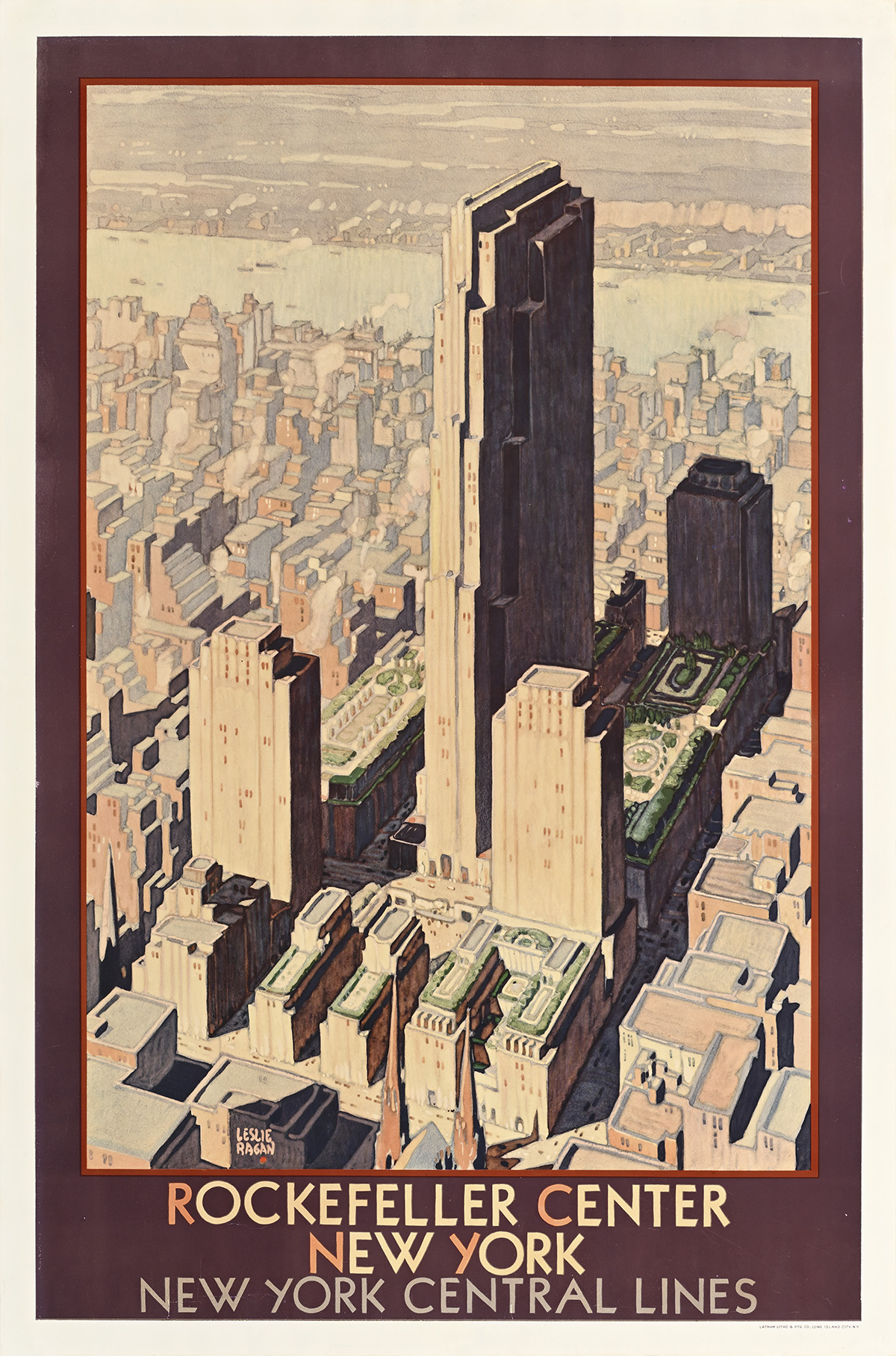

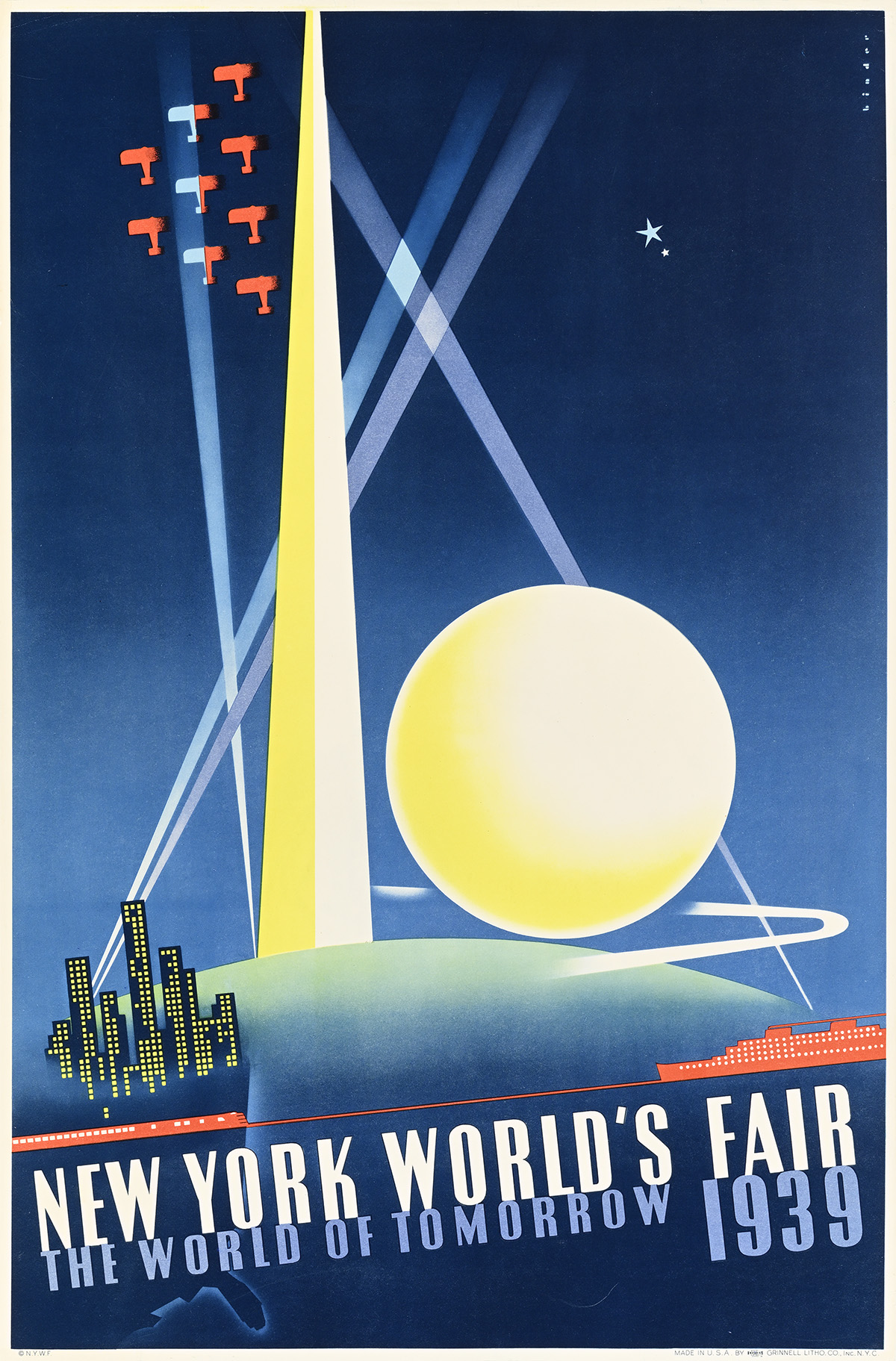

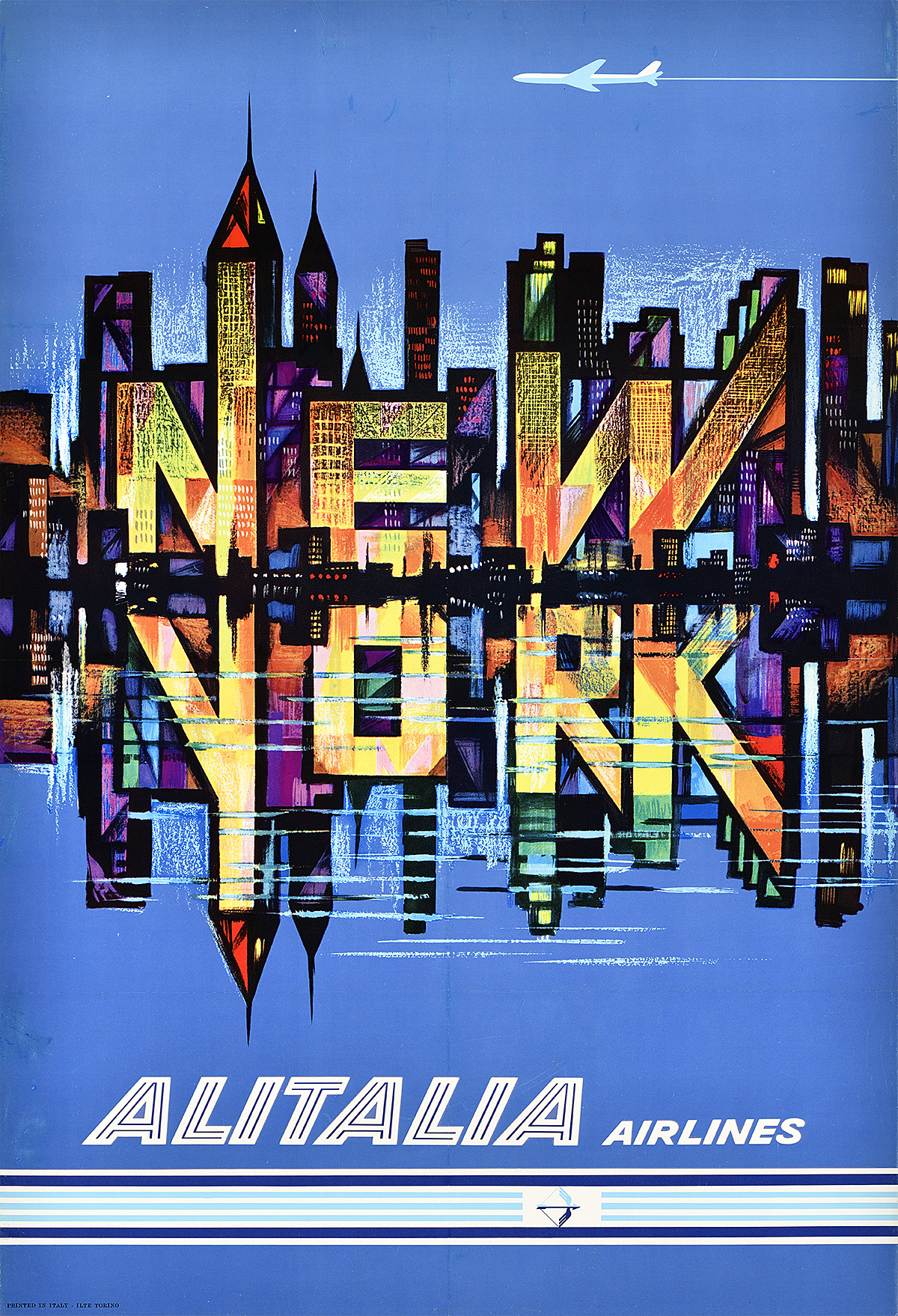

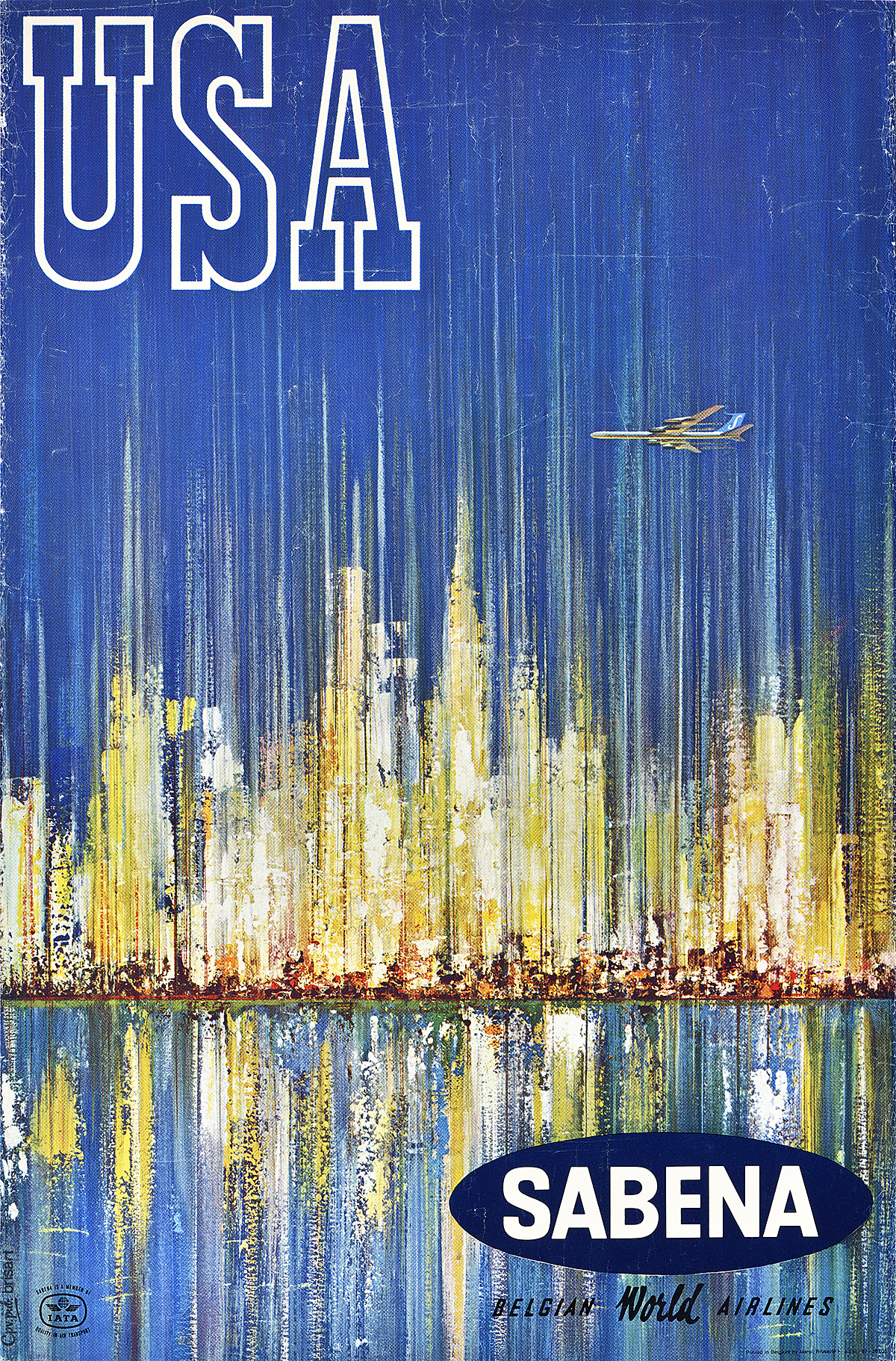

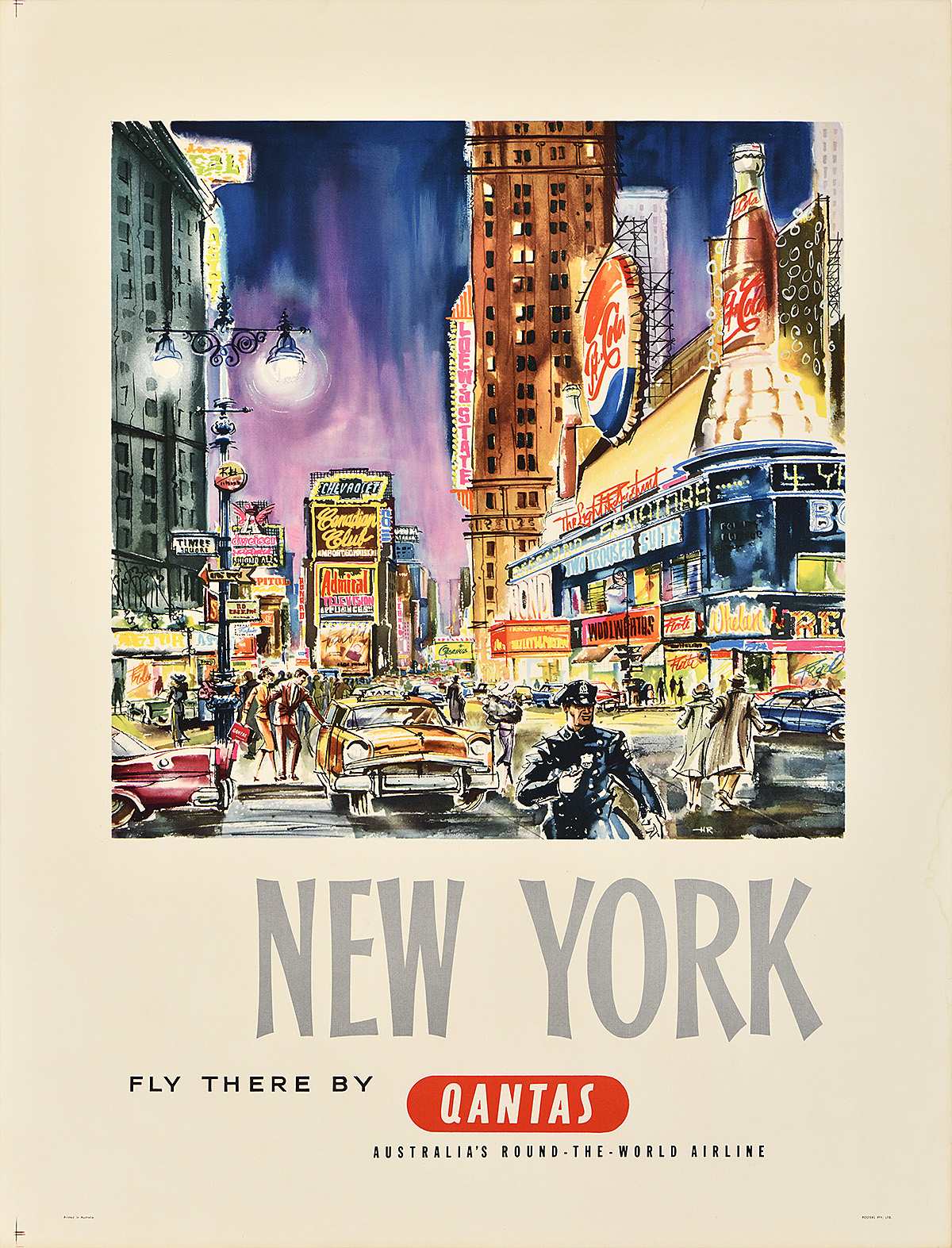

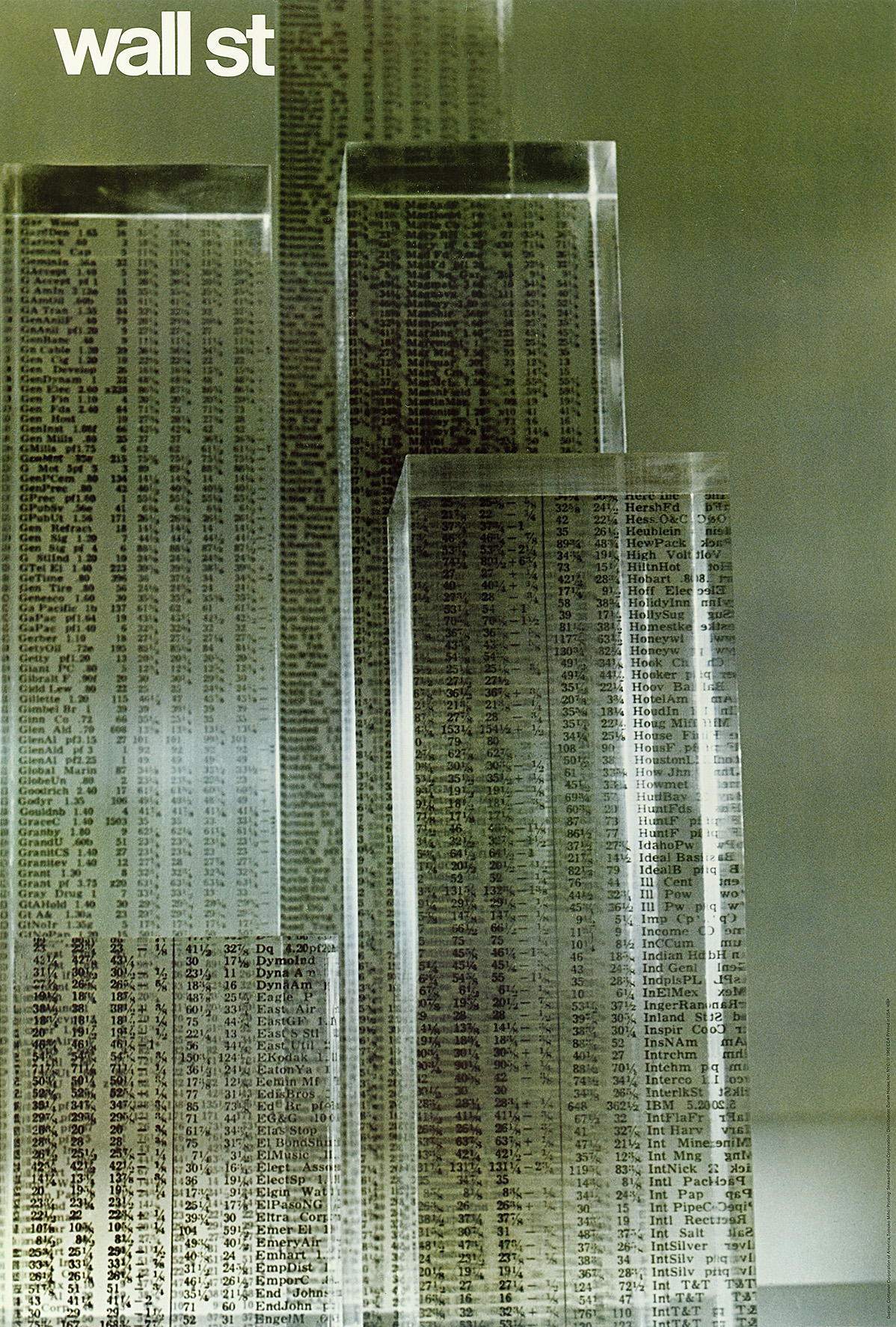

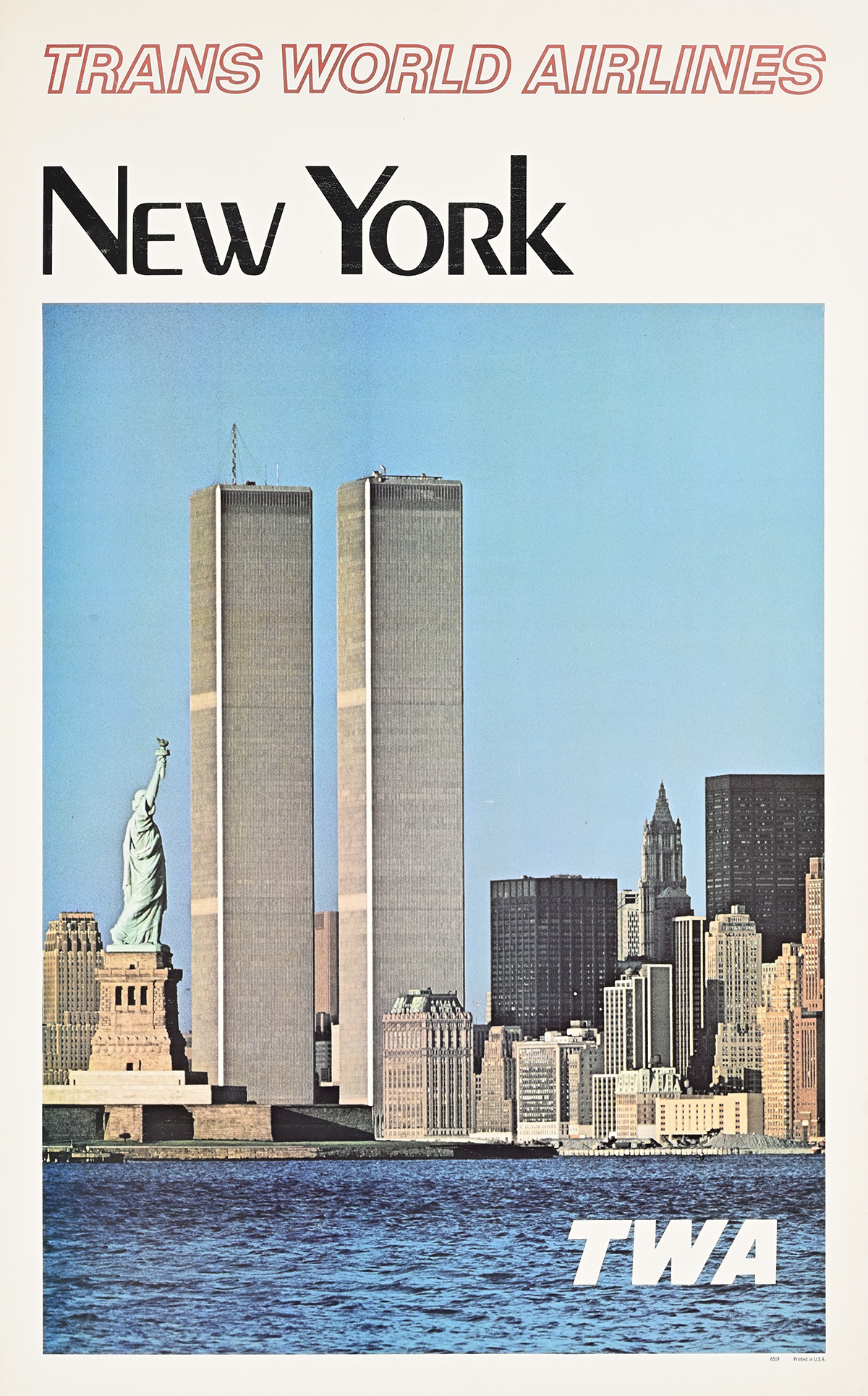

As the city grew, it became a hub for rail transport and sea travel; a point of entry for immigrants, merchandise, and dreams; and the commercial capital of the nation. It soon evolved into a bustling, thriving urban center. The opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 and the dedication of the Statue of Liberty in 1886 introduced two impressive landmarks that began to shape the city’s modern visual identity. When, in 1898, greater New York was consolidated into a single city consisting of five boroughs, it also emerged as one of the world’s largest urban areas, second only to London in terms of population. Further, from the 1870s, a series of skyscrapers slowly began to populate the skyline; the process escalated in the 1890s—when the term began to be commonly used—establishing the densest concentration of tall buildings in the world at the time. From the 1870s, too, a system of elevated trains ran throughout the city; these were fully electrified in the early 1900s, and, by 1904, a subway was running underground. It was hardly an exaggeration to call this buzzing, dramatic, unique place a “Wonder City.”

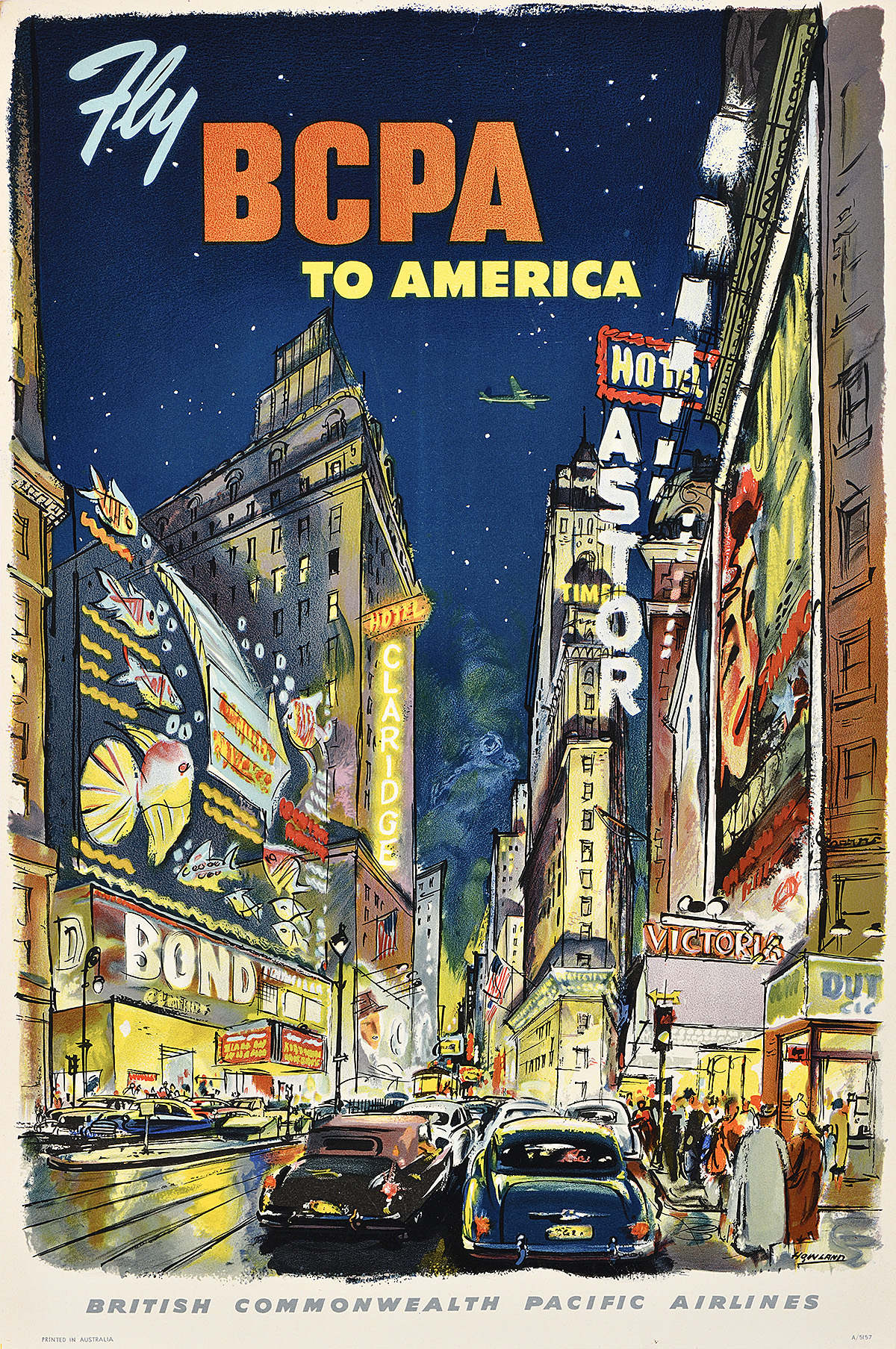

The phrase, the brainchild of marketers, had appeared in newspaper and magazine advertisements and articles sporadically through the final decades of the 19th century. A number of cities around the country and in Europe also used it in their promotions at that time. By 1914, the phrase had also appeared on a New York souvenir booklet. Such popular keepsakes, along with postcards and postcard books, spread images of the city and its nickname. Previous efforts by advertisers to sum up New York in a distinctive manner had been less successful; phrases like the “American Cosmopolis,” “The First City of the World,” “City of Marvels,” and “The Foremost City in the World” never really gained traction. Nonetheless, the fact that New York was truly a “Wonder City” was apparent to all.

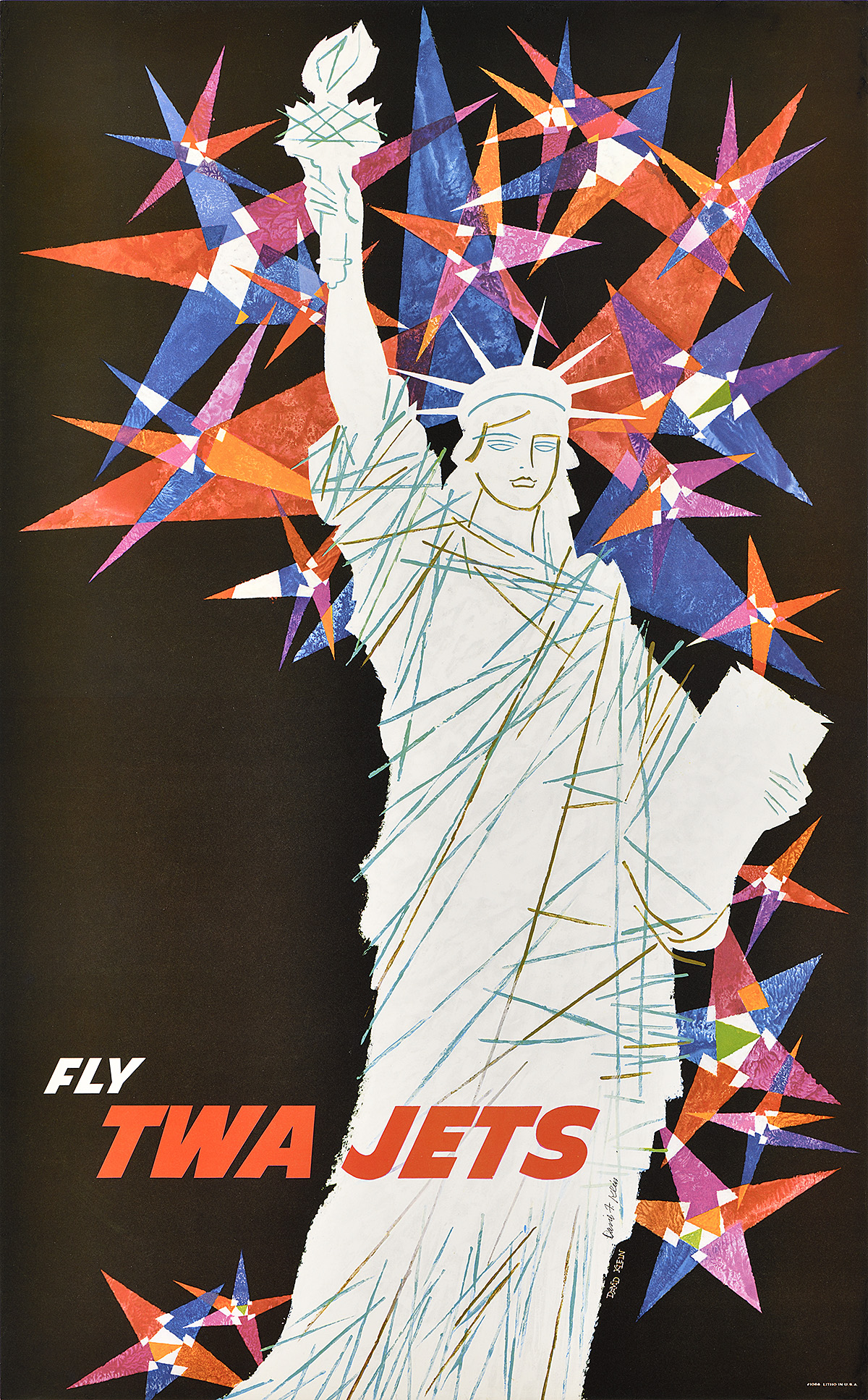

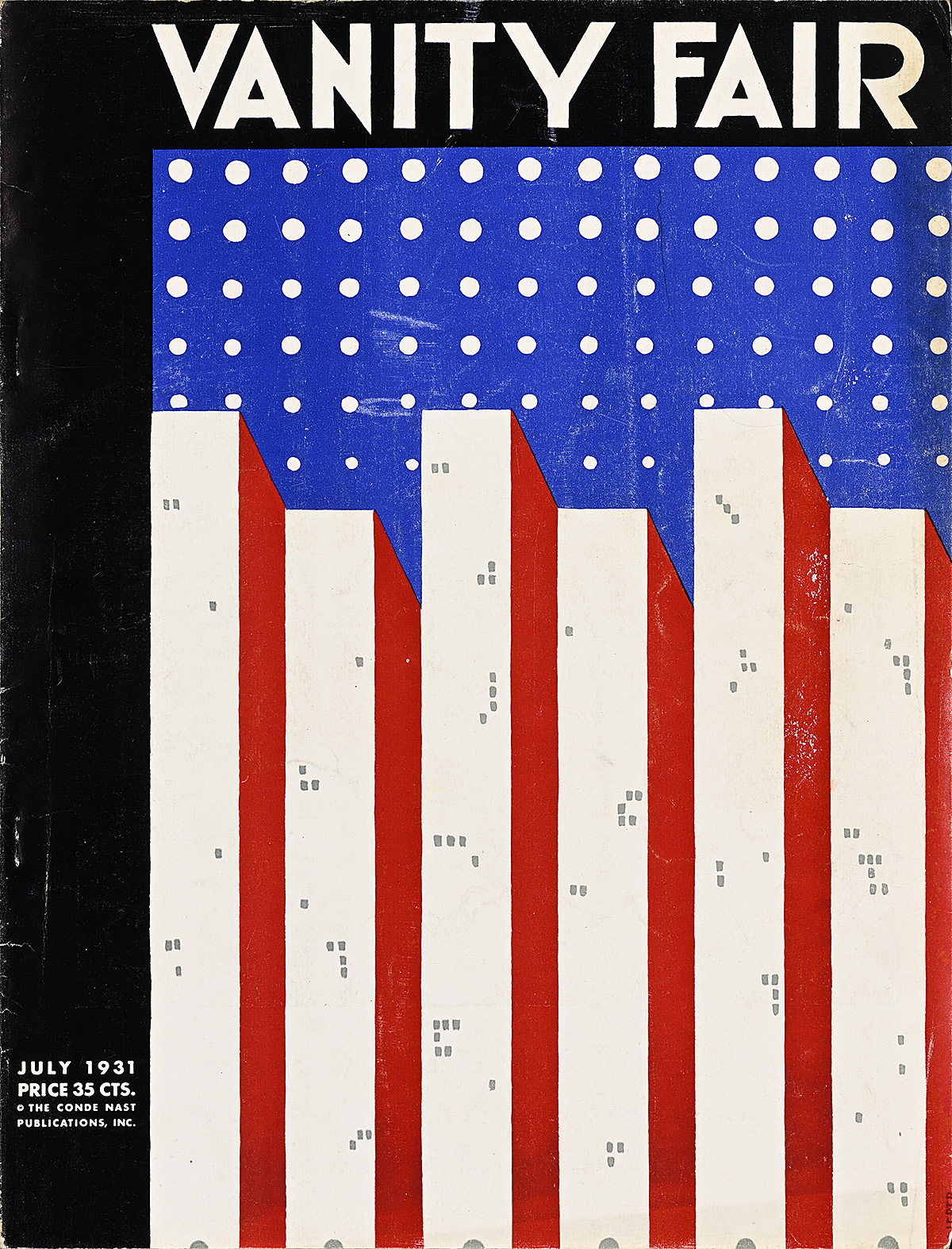

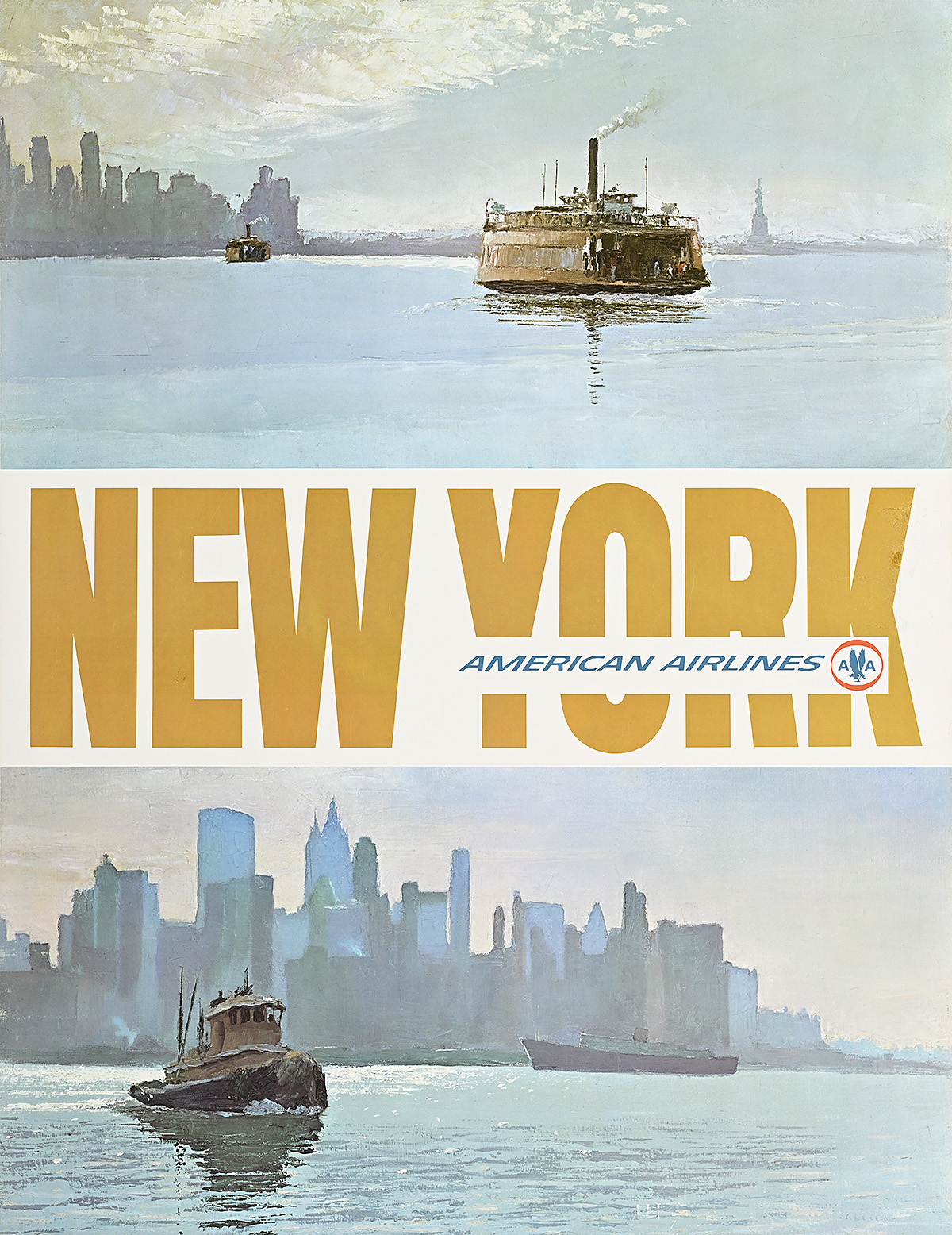

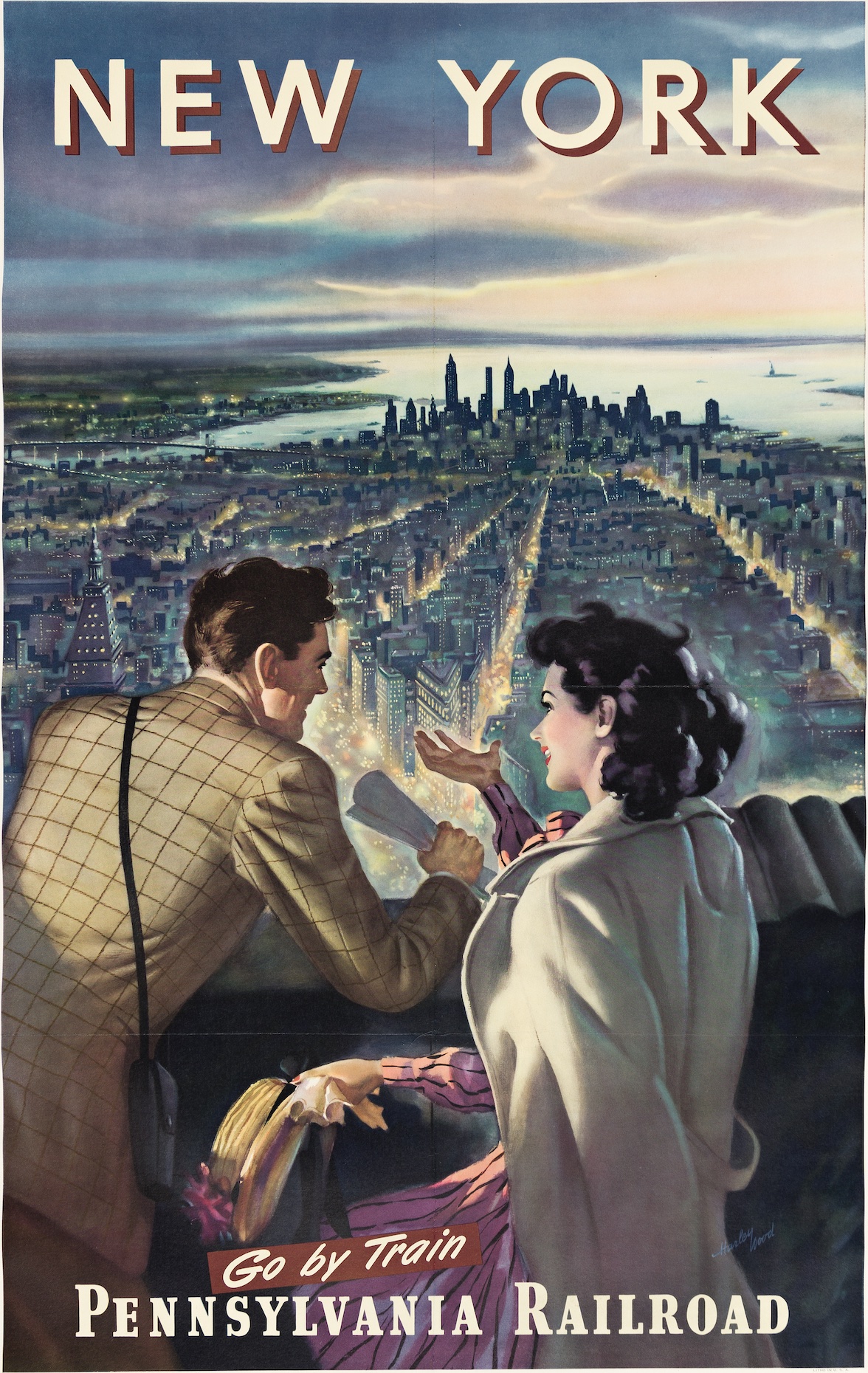

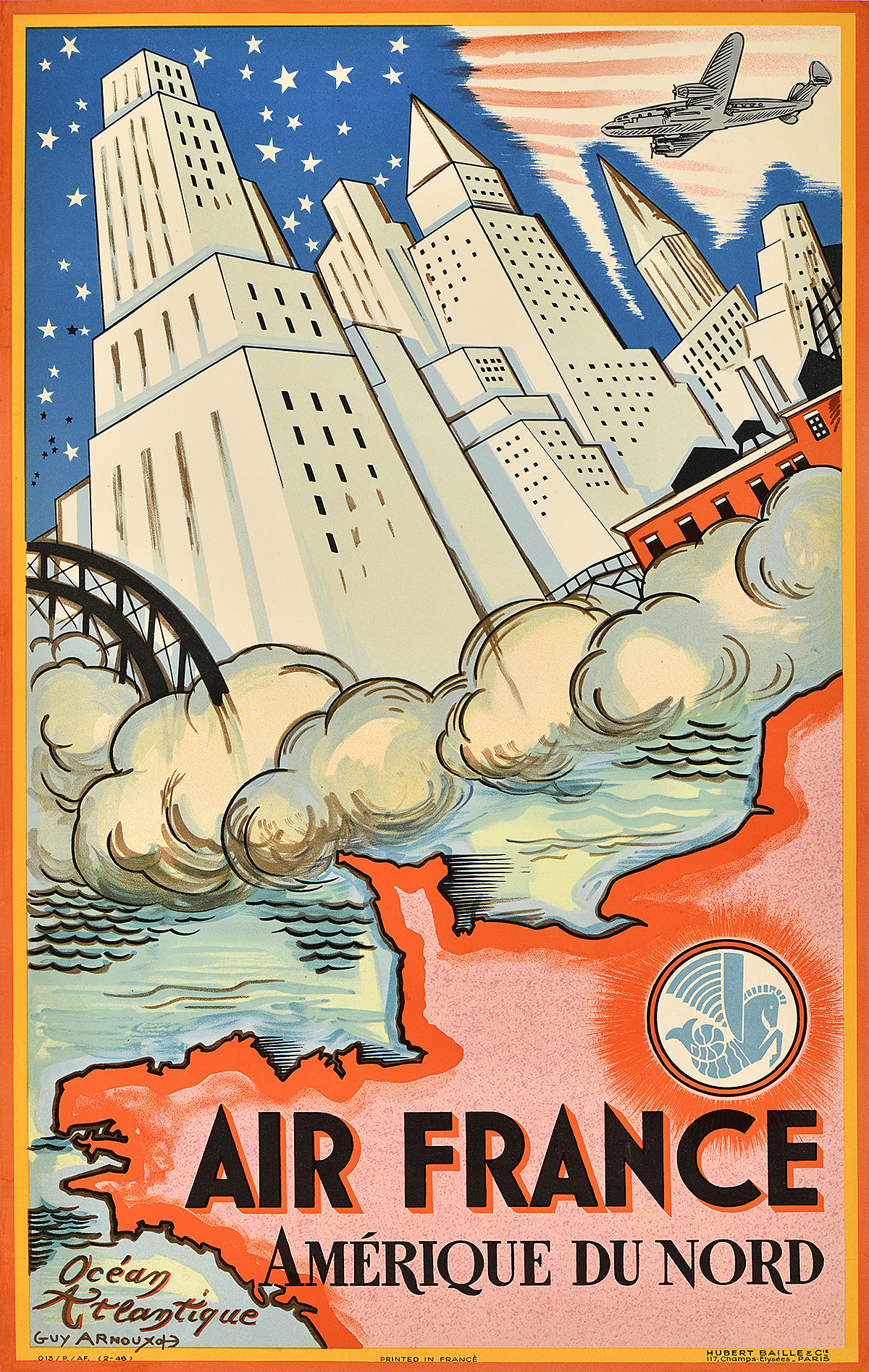

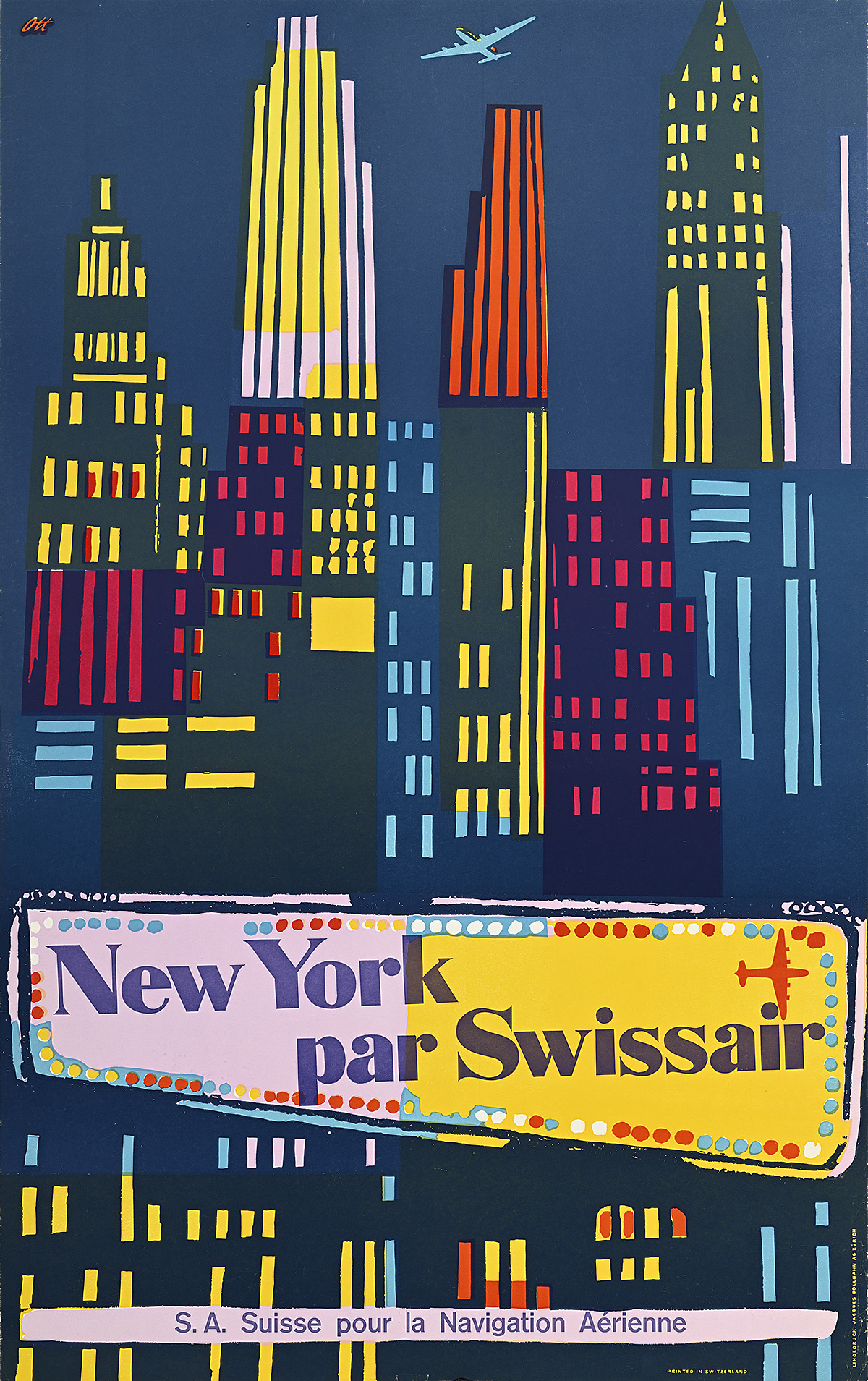

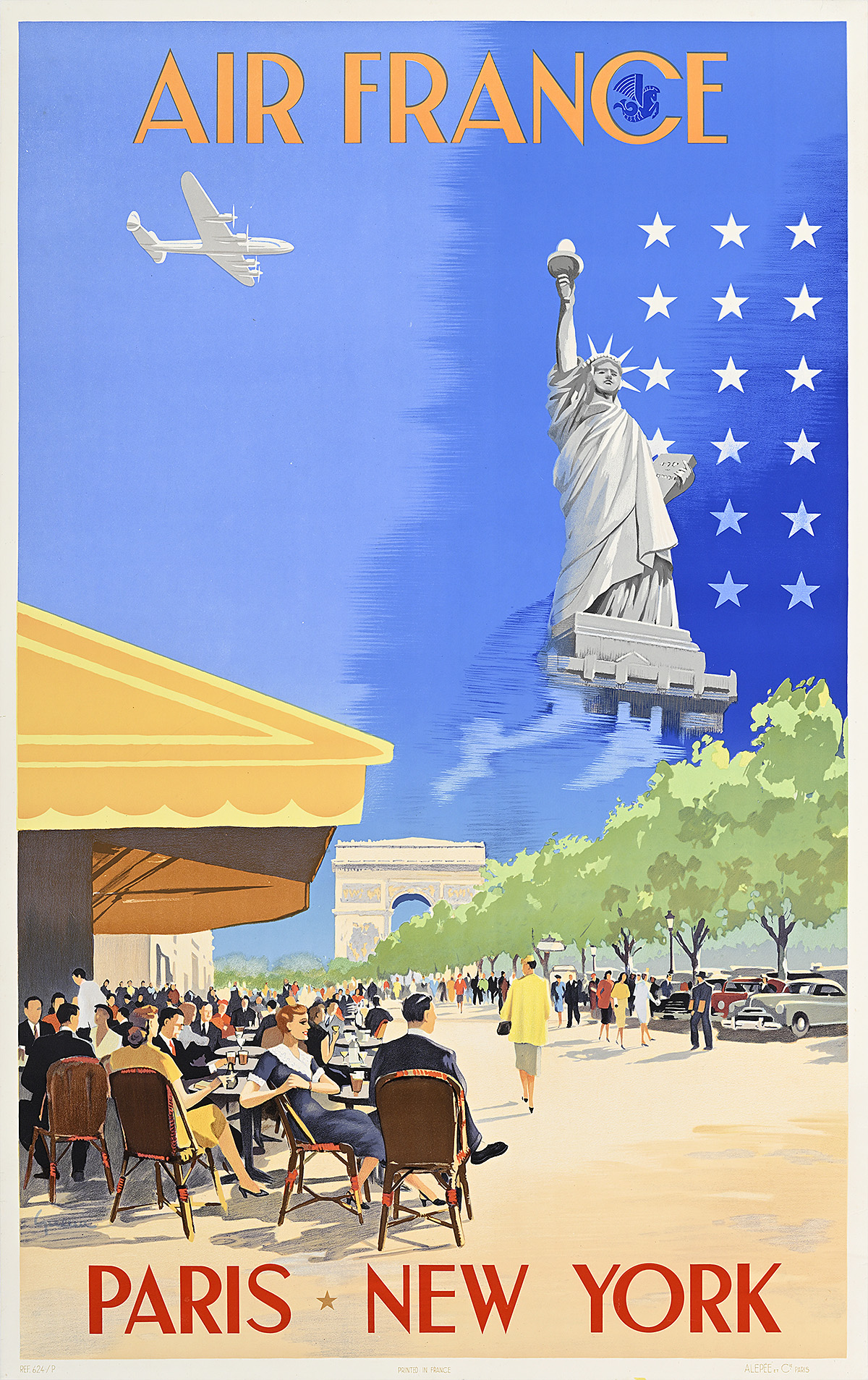

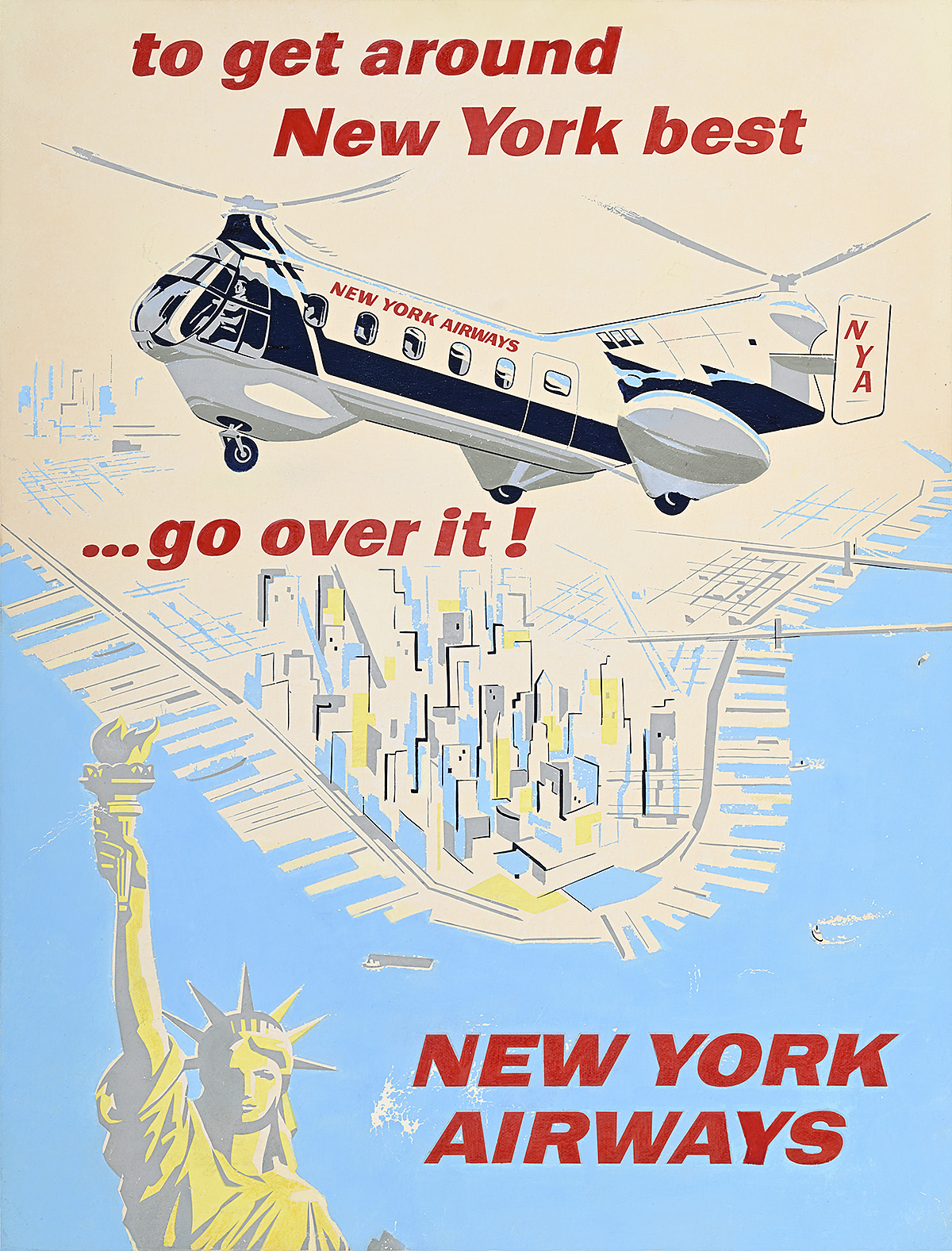

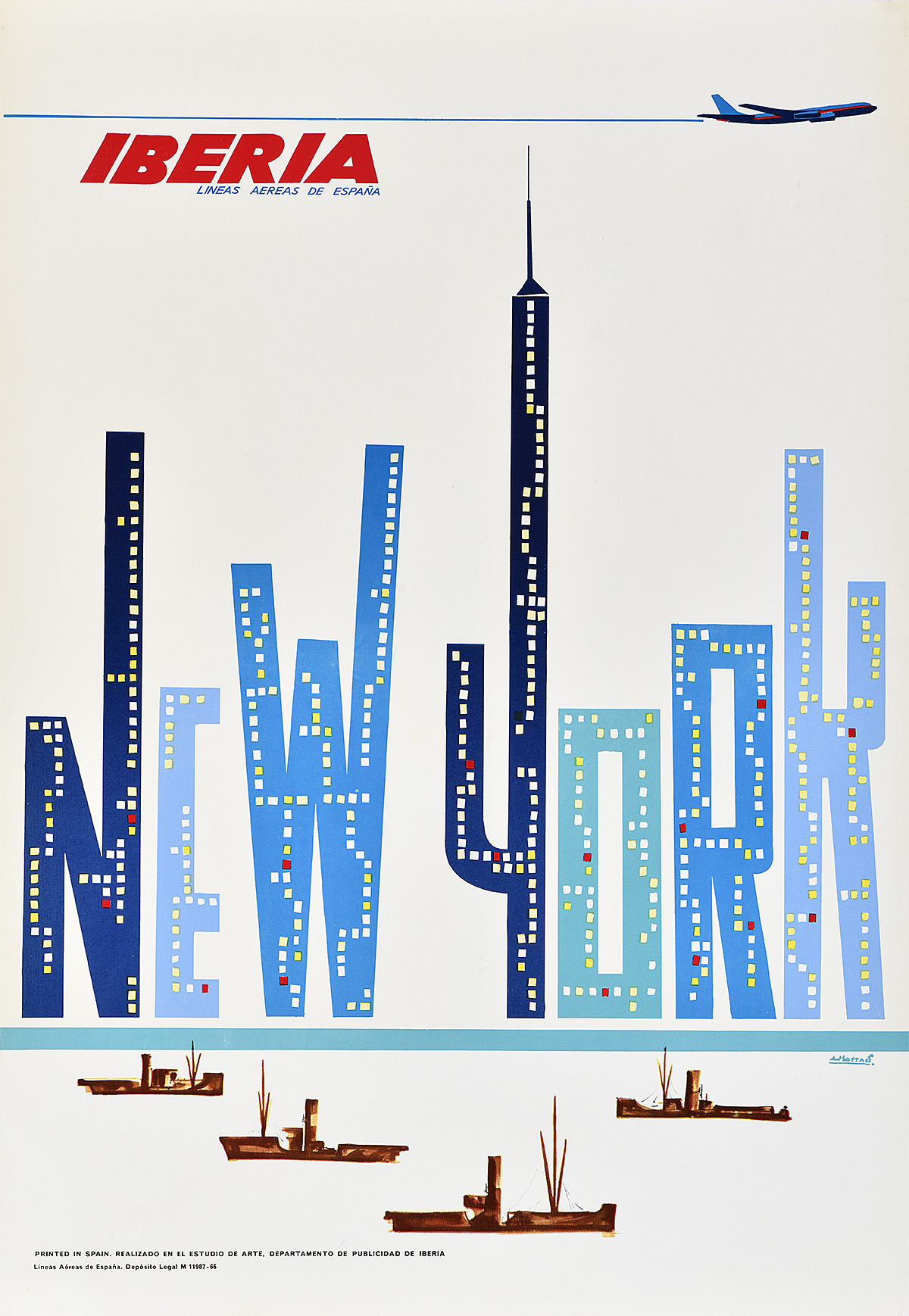

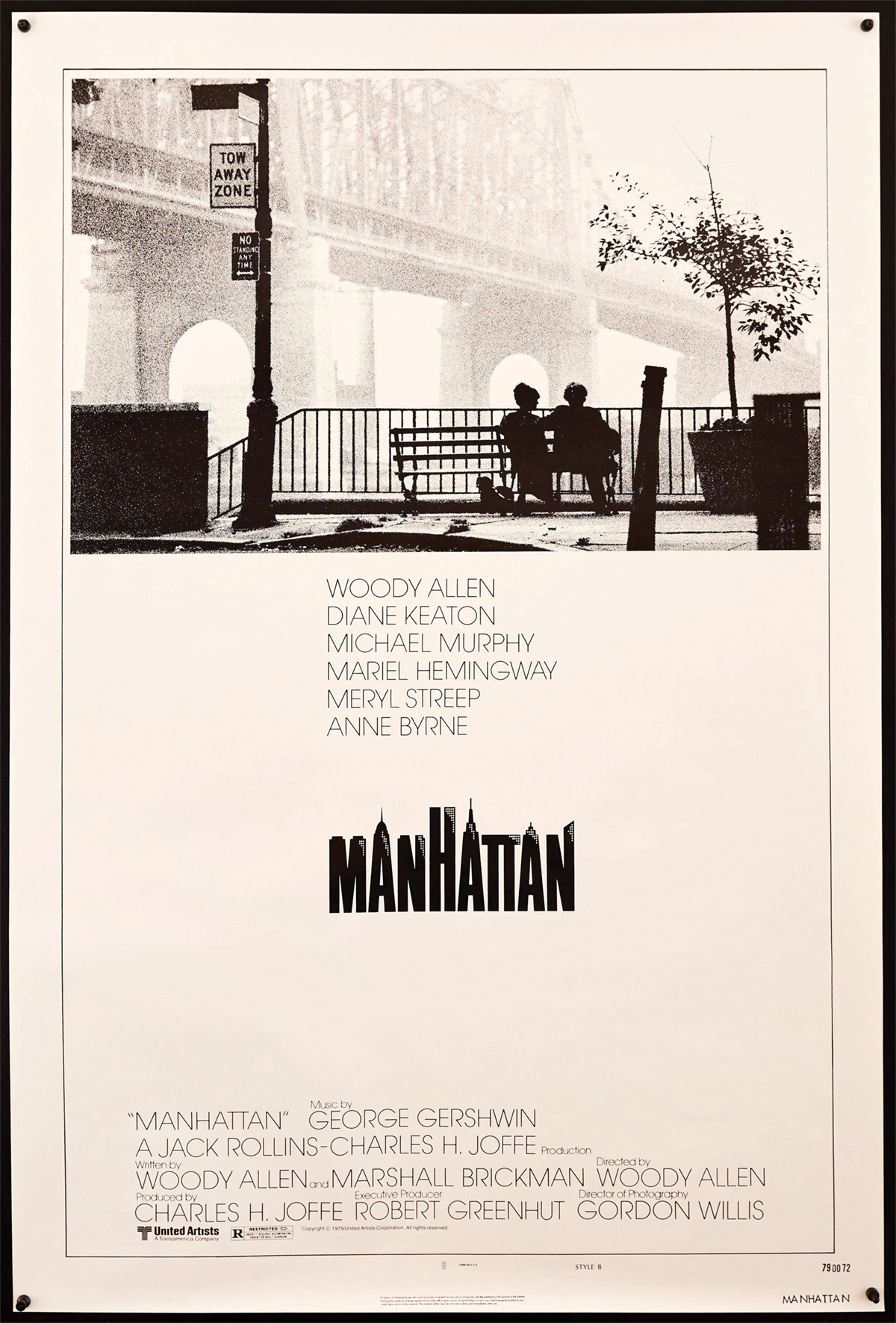

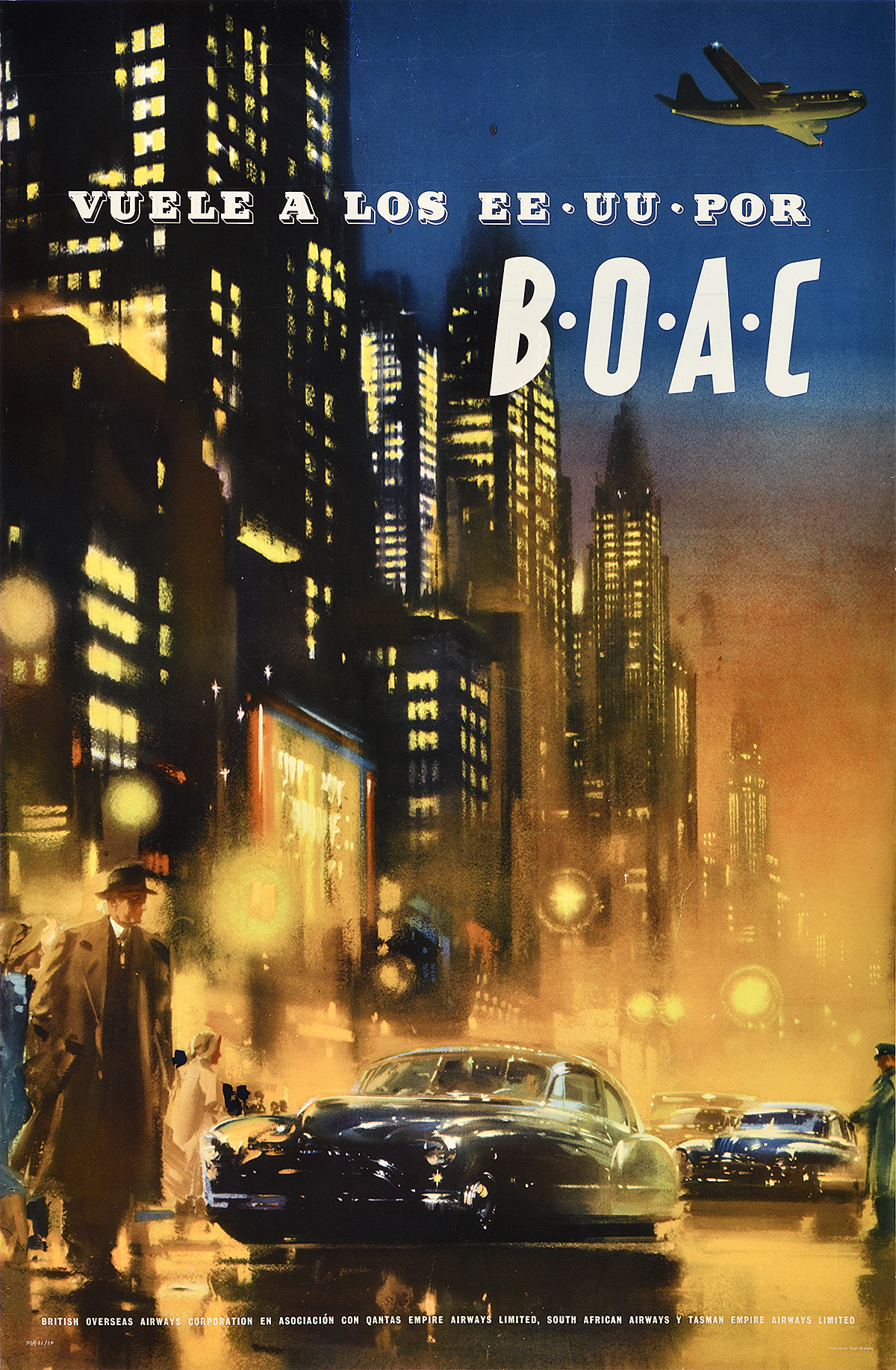

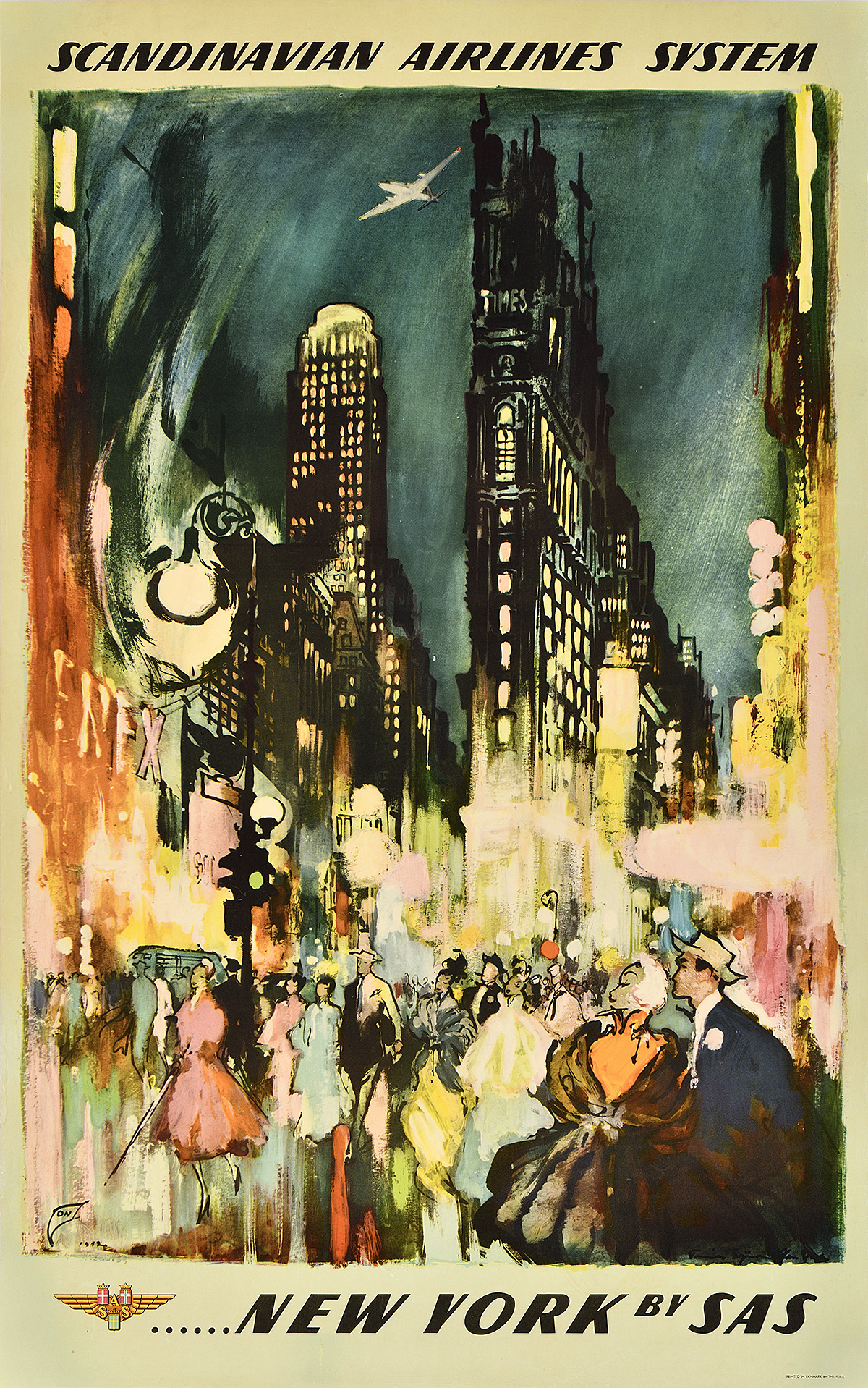

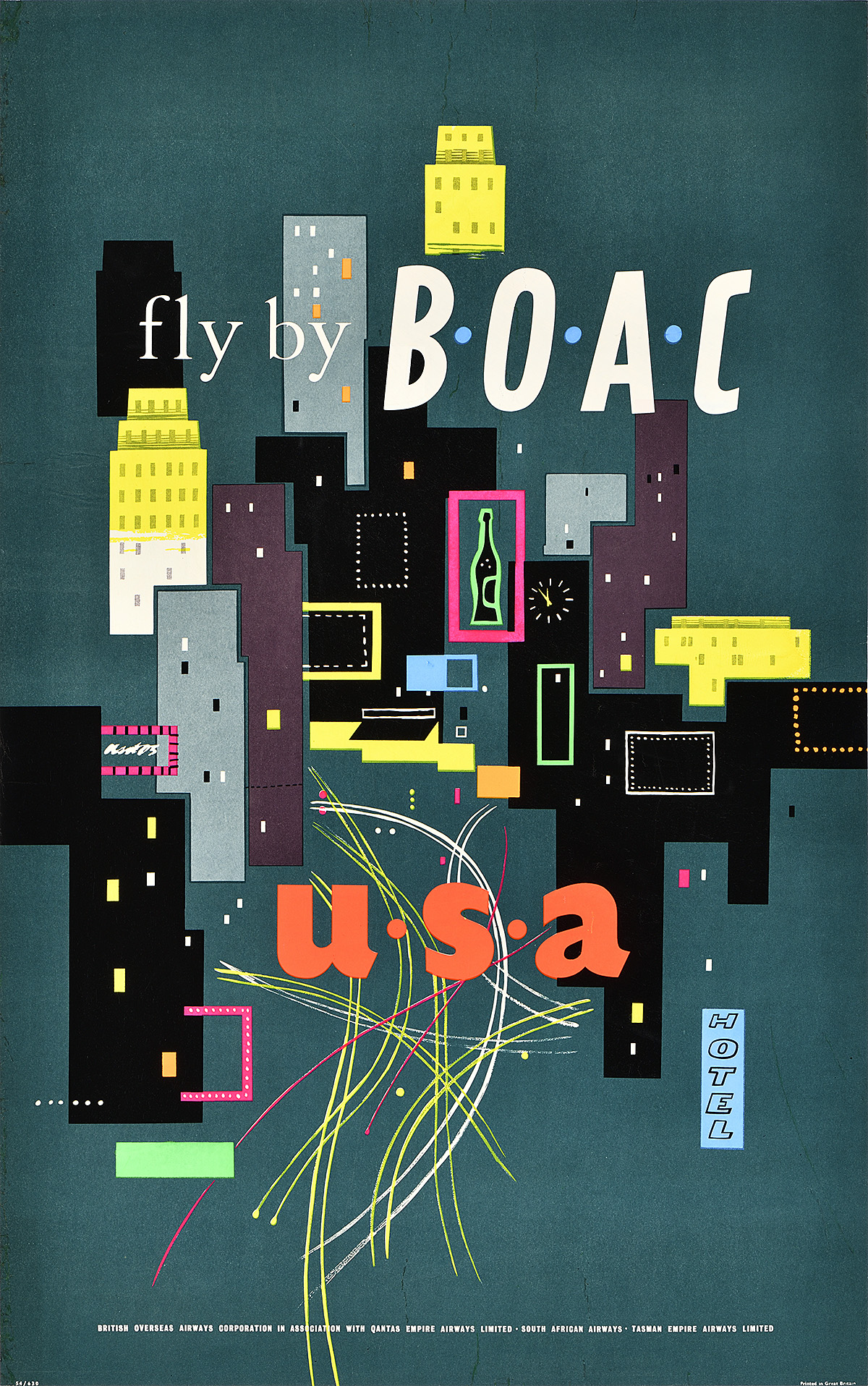

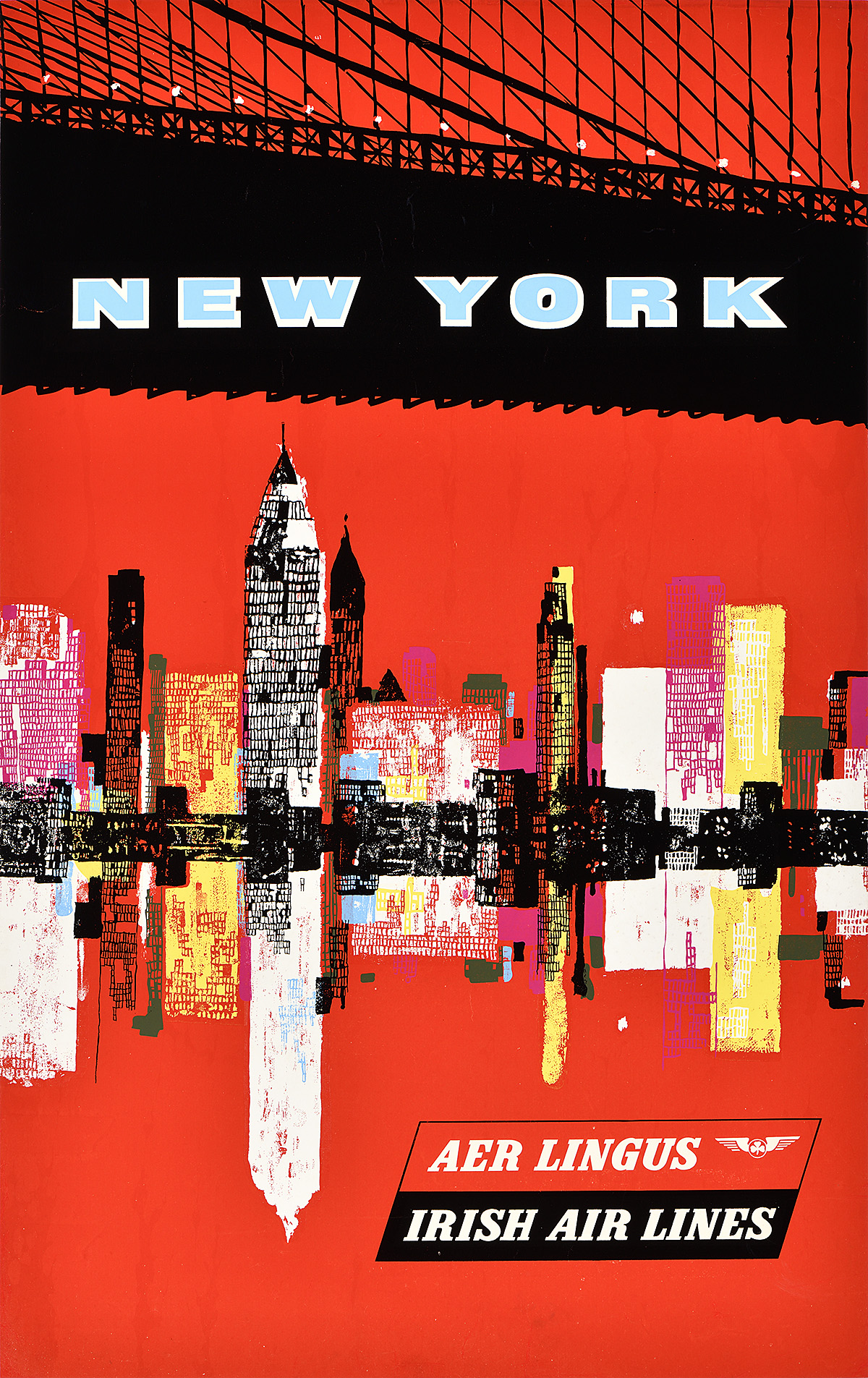

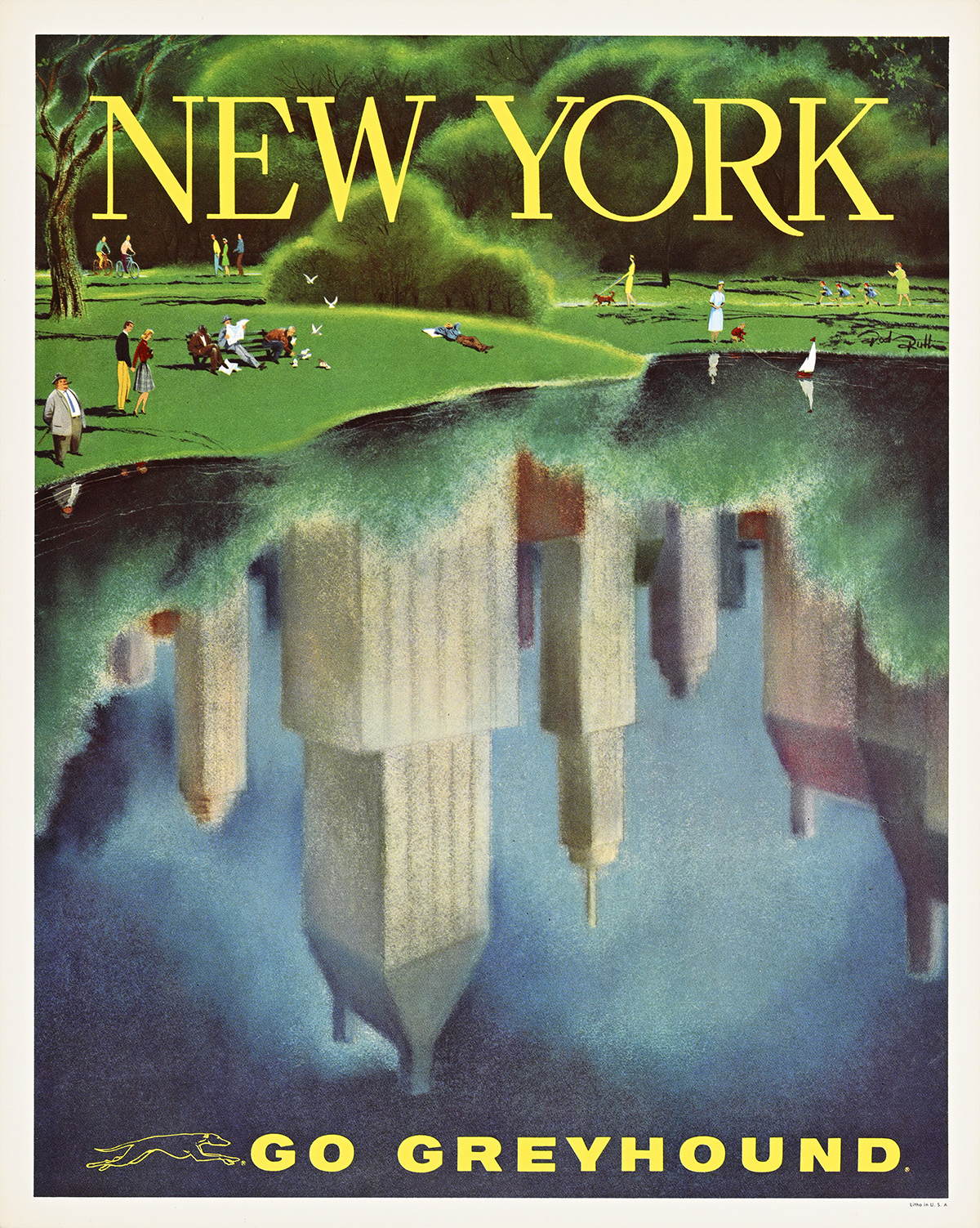

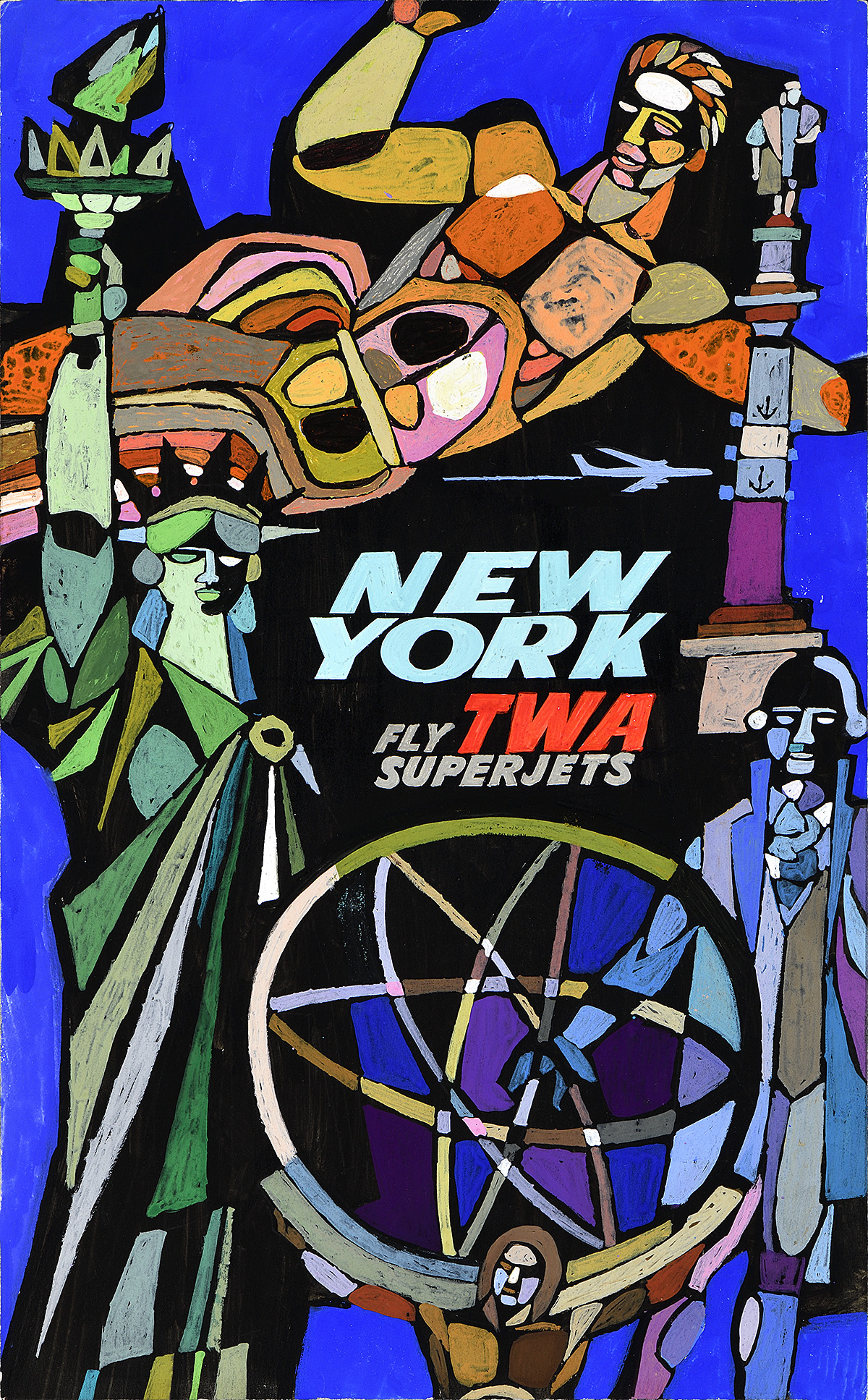

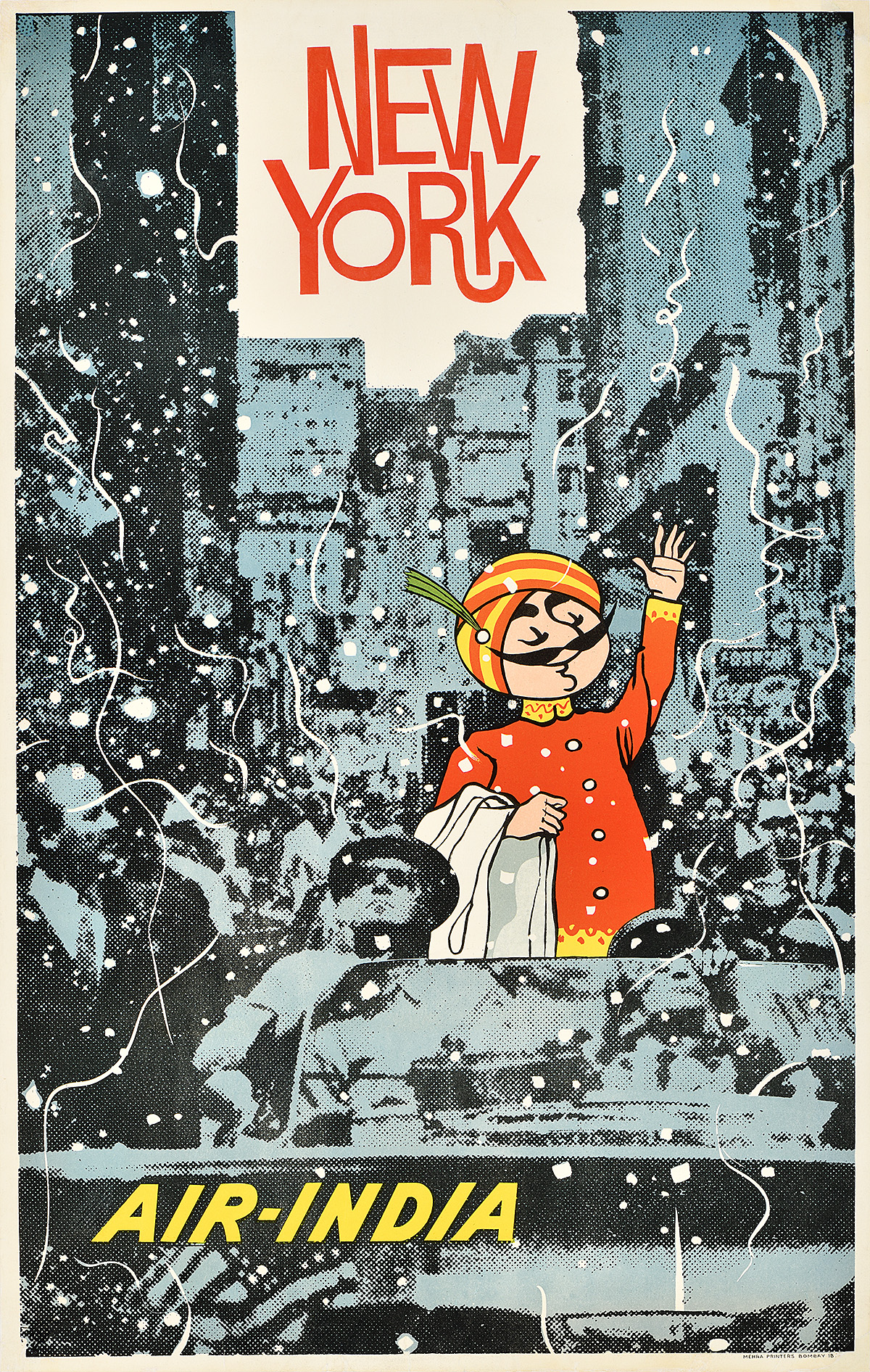

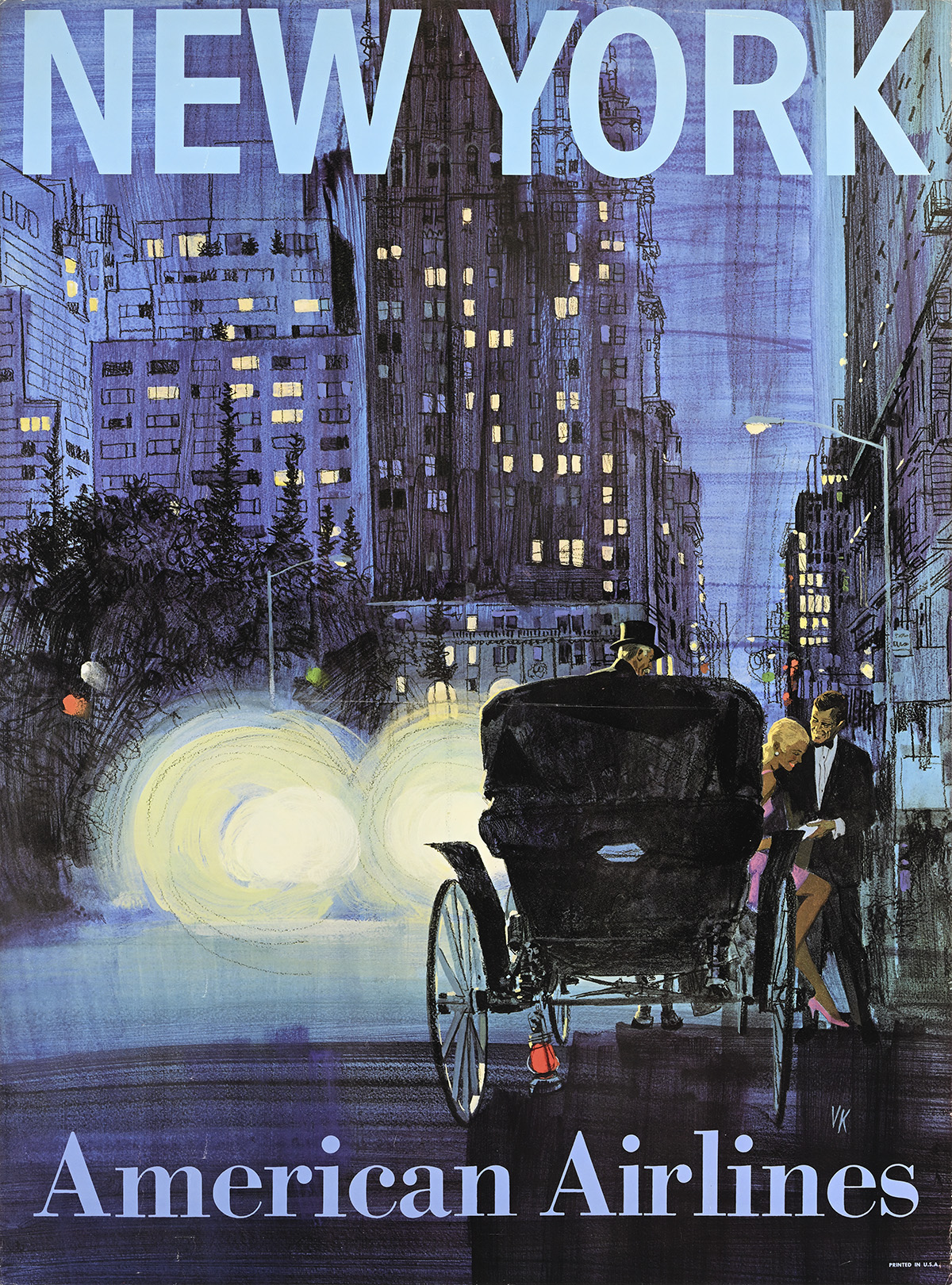

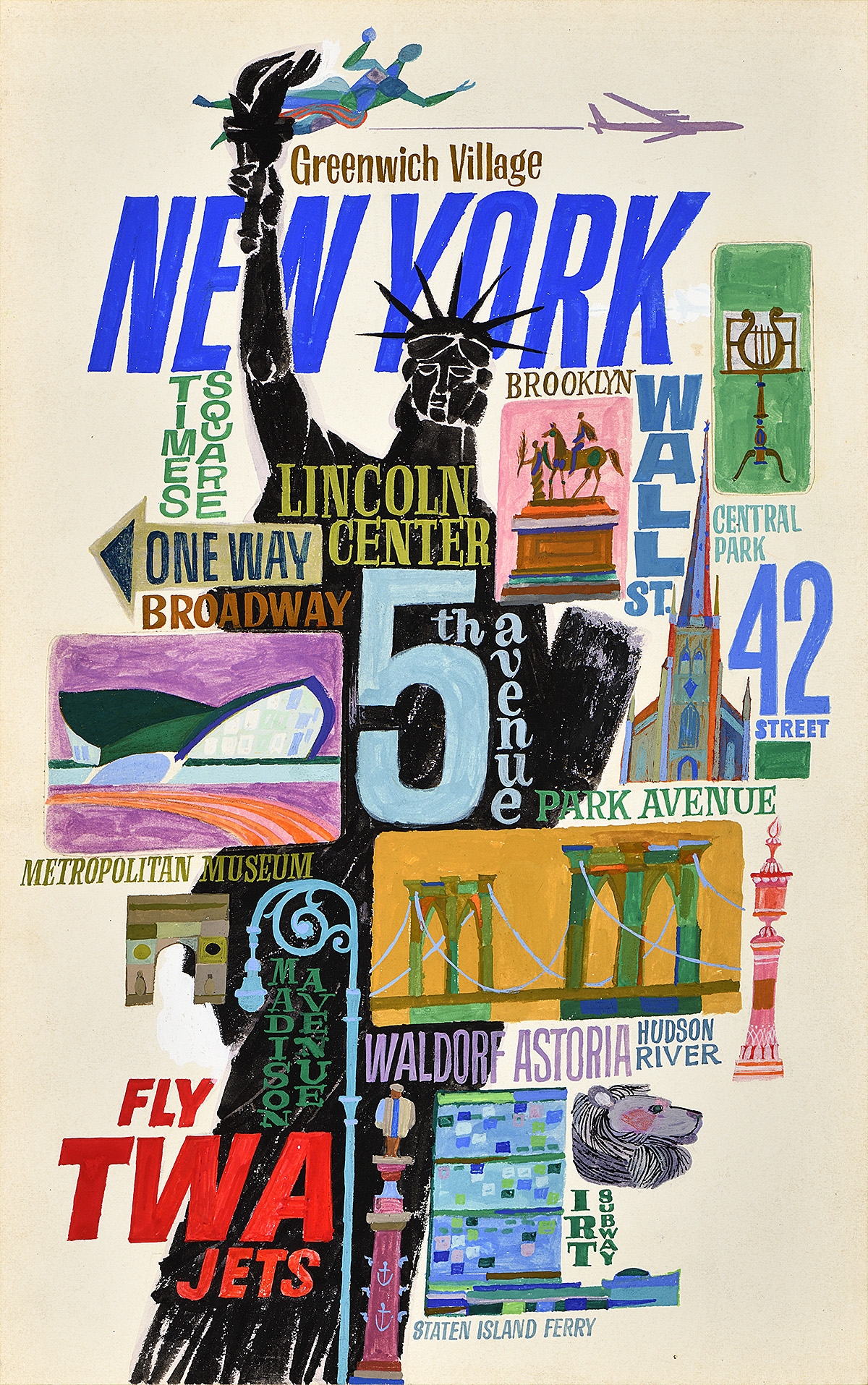

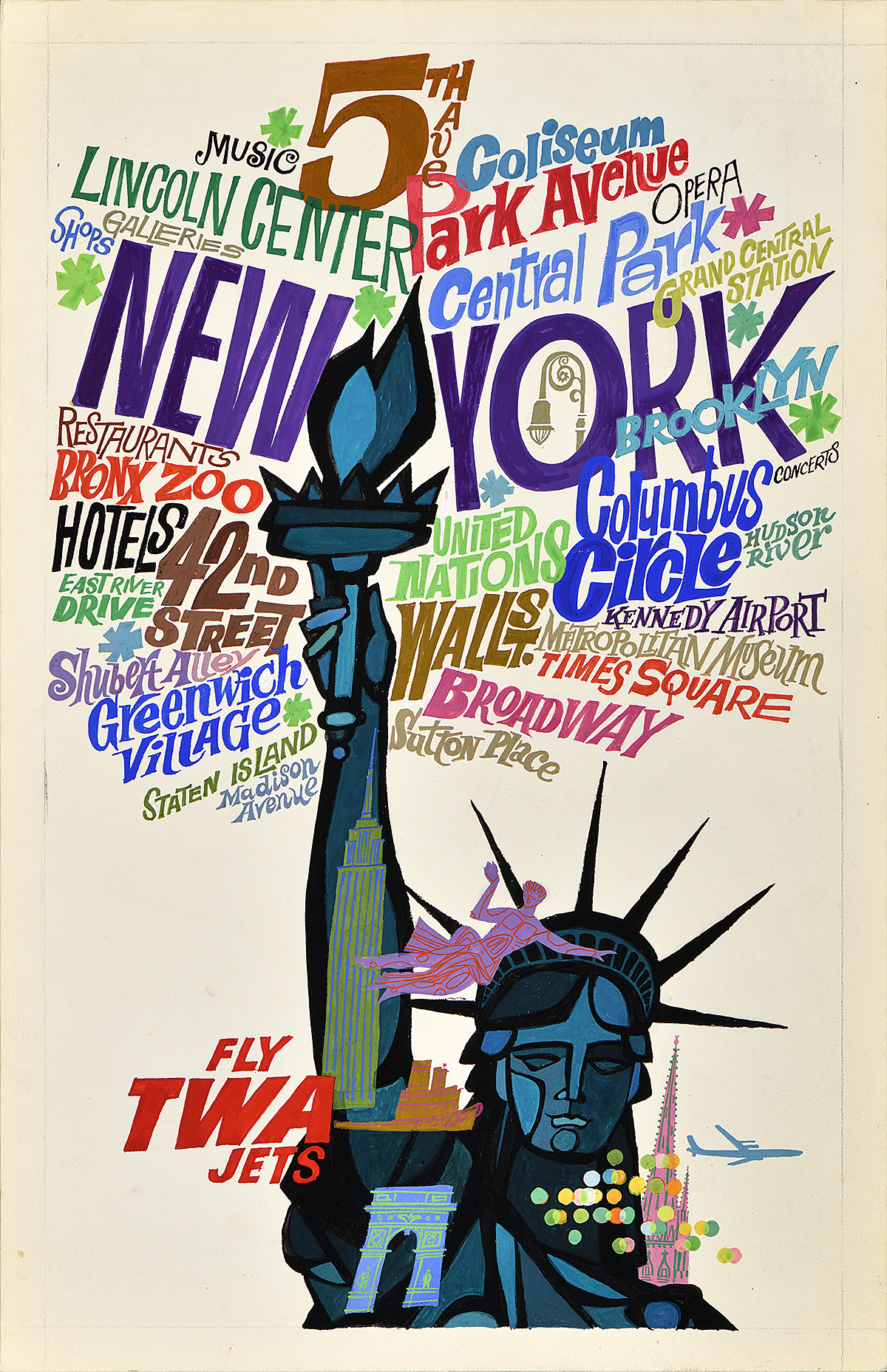

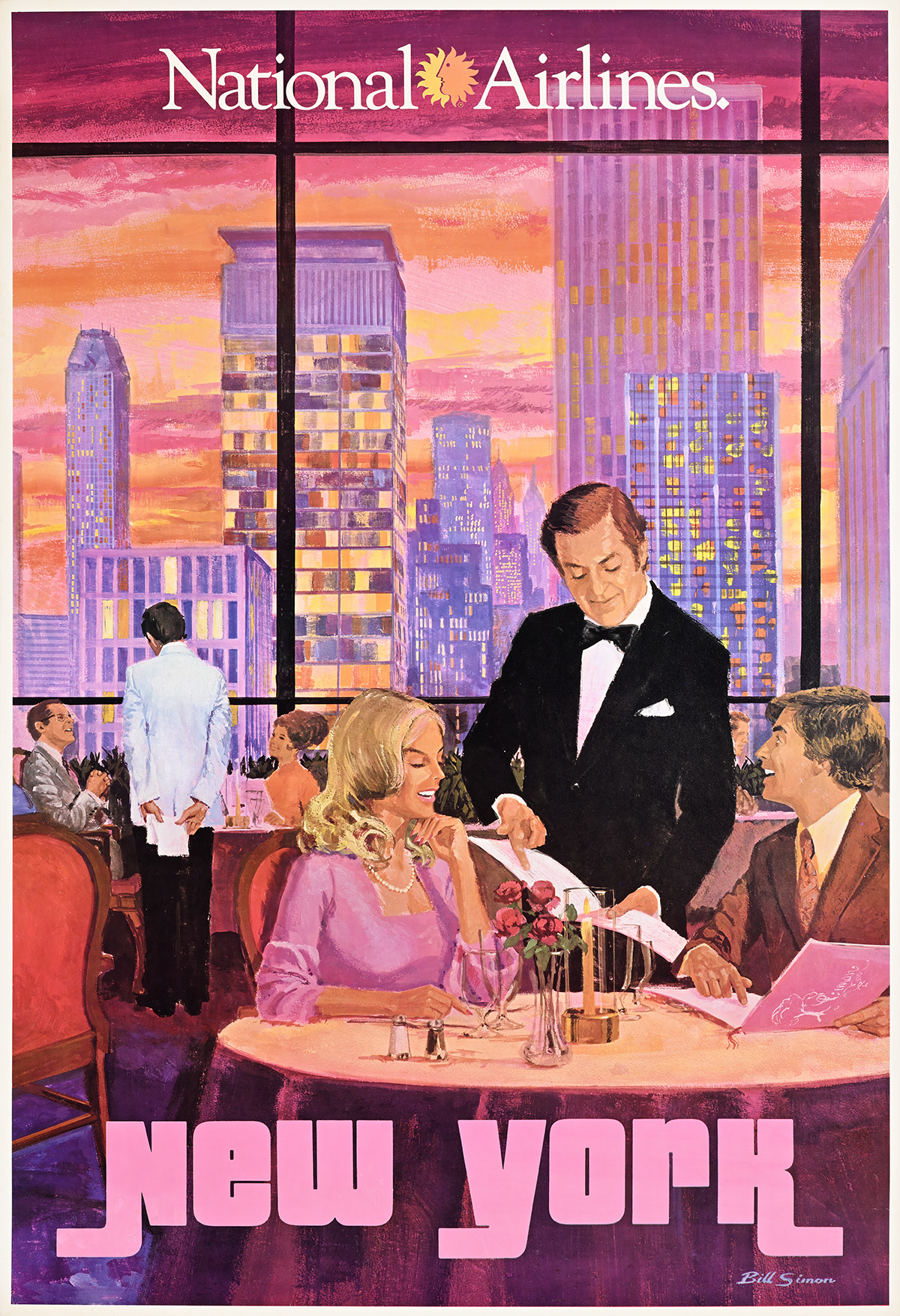

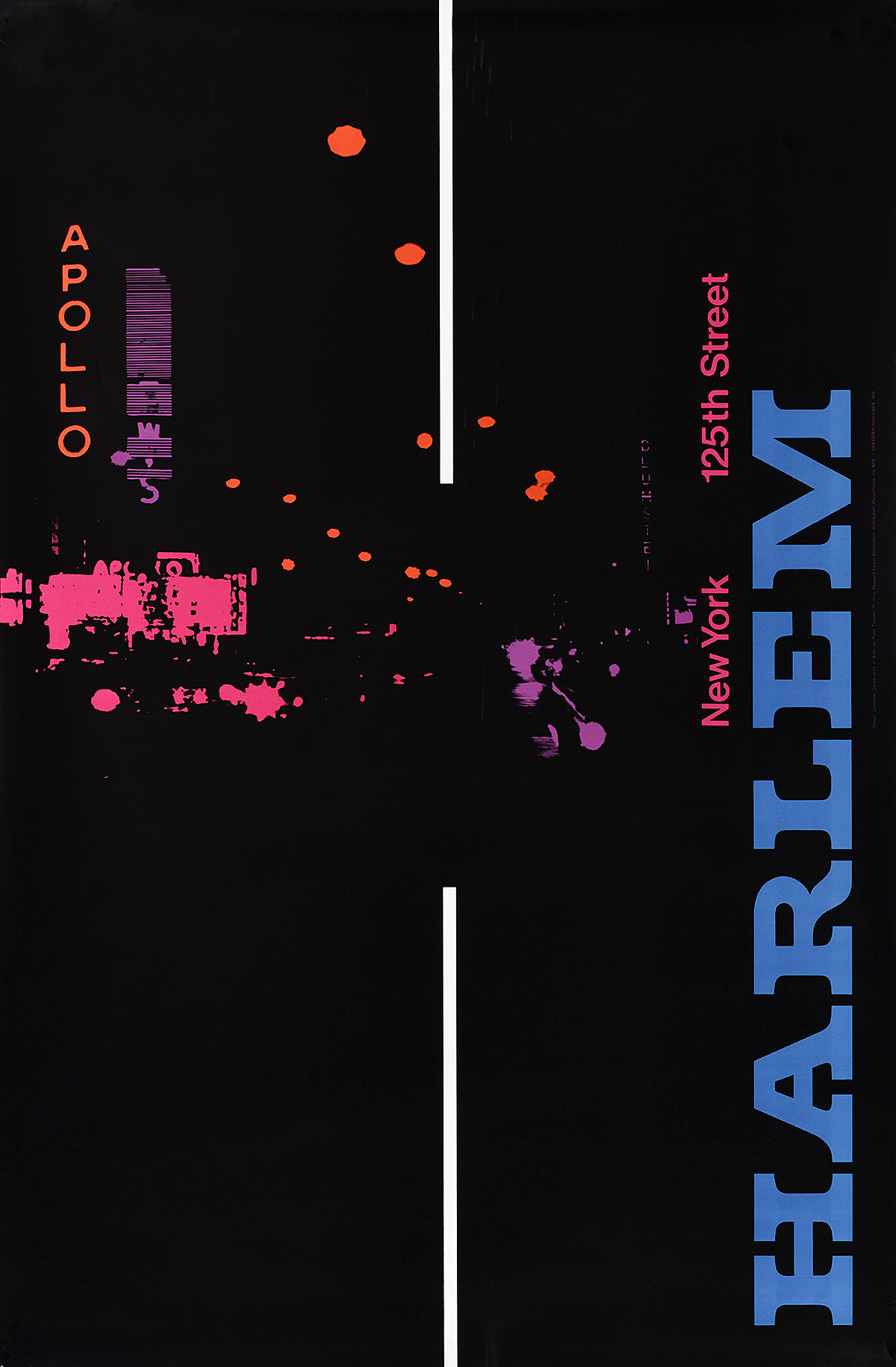

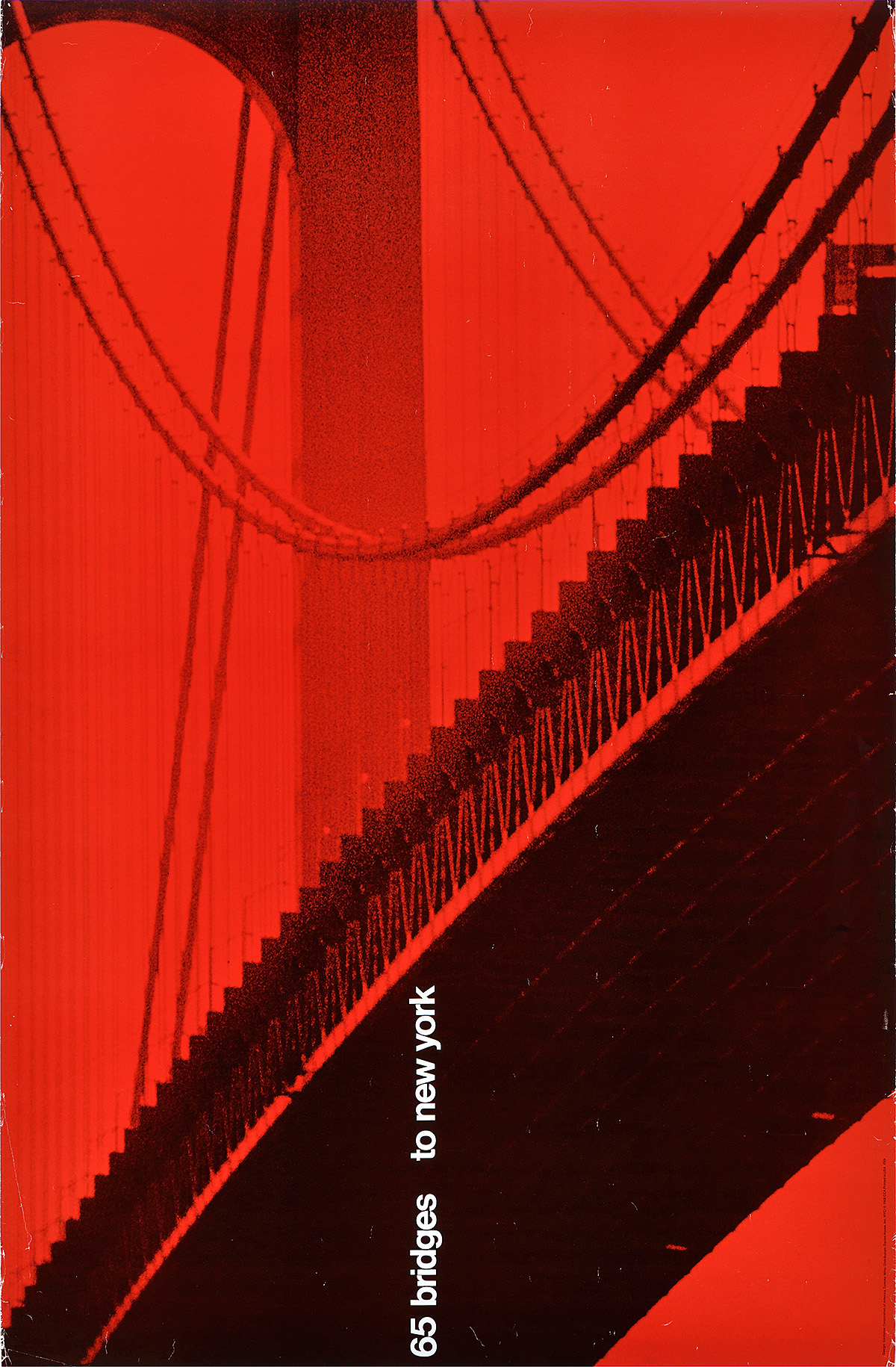

New York’s explosive growth from the end of the 19th century ultimately produced more travel posters than were designed for any other city in the world, a host of images as varied as its ever-shifting identity, showing it from the water, from the ground, and, eventually, from the air. This exhibition will track how New York City was represented to travelers, immigrants, and tourists over the decades. It is a visual, graphic experience, one that encourages the viewer to exult in all the ways artists captured the multitude and the magnitude of the thriving metropolis, selling the hustle and the bustle, the bright lights and the imposing structures, sometimes representing moments of intimacy and slice-of-life imagery within the urban canyons and among the ziggurats.

Large text is available at the Info Desk.

Guías con letra grande están disponibles en informaciones.